Effacing the Body

Effacing the Body

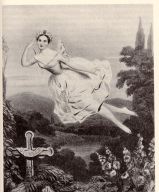

The striving for this quality of airiness is significant. Unlike Magri who remarks upon the strength of Pitrot in his ability to balance “his whole body upon the tip of his big toe”, a woman’s virtuosity en pointe was displayed through the seeming effortlessness of her techniques. This expectation is clear in the comments of Marie Taglioni, the woman credited with having perfected the art of dancing sur la pointe (Guest 1965):

"…

she [Amalia Brugnoli] is a dancer who introduced a new style;

she did very extraordinary things on the point of her foot which was narrow

and long,

very advantageous for this kind of dancing. She was thin, rather small,

not very pretty, but pleasant; I did not find her graceful because to rise

up on her pointes she was obliged to make great efforts with her arms.

However, she was an artist of much talent." (p. 13)

arms.

However, she was an artist of much talent." (p. 13)

The importance of the appearance of effortlessness in further underscored

by Janin in 1832 in his comparison of one danseuse’s “large

foot squashed and flattened by exercise” (Chapman

1997) with his

description of Marie Taglioni in the same review: “…natural,

flowing, graceful without trying to be, with unparalleled elegance of form,

with two arms

like supple serpents and legs like arms, and the foot of an ordinary woman” (Chapman

1997).

The appearance of exercise, stiffness and physicality was not permitted

in the techniques of the ballerina. The reality of the physical exertion

and rigorous training necessary for the perfection of pointe work was effaced

to maintain the expectations of feminine

grace and beauty.