HELLFIRE SELECTIONS—PURITANS AND CAUTIONARY TALES

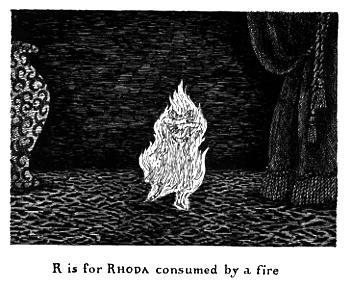

Edward Gorey’s “Gashleycrumb Tinies”

will look familiar to many of you (Refer to CR #1)

WHAT MAKES THESE IMAGES

FUNNY/AMUSING?

·

very ghoulish kind of humour: seems like the last thing

you’d present to a child reader

·

yet much of the ironic “charge” of Gorey’s work is that it

so closely resembles many of the earliest e.g.s of lit for kids

·

RHODA’S death—like that of Augusta Noble (Sherwood) and

Poor Pauline (Hoffman)

·

Prue & Zillah seem to warn against the dangers of

alcohol, for e.g.

·

a few (e.g. K is for Kate) look like horrific but realistic

scenes

·

most of the deaths are simply ridiculous (olive run thru

by a flying awl; yorick & falling timberà much as

Hilaire Belloc’s Rebecca has her head smashed in by a marble bust)

·

note also the impassive expressions and formal clothing of

the children: this contrasts with their violent fates and also distances the

images from the viewer

The earliest history of children’s literature is dominated by such scary stuff because it comes from the Puritans.

THE ORIGINS OF A (WRITTEN) LITERATURE FOR CHILDREN

Before the Puritans: There really wasn’t much in the way of literature written specifically for children.

The earliest English schools were attached to monasteries.

Their primary focus was teaching Latin (language of the Roman Catholic Church) to young boys who would become priests and monks; Church principles dominate curriculumà e.g. Math classes centred on church calendar, calculating Easter

Very few early medieval children—even wealthy ones—ever encountered a manuscript or book, and certainly children from other walks of life never met with any but oral literature.

But after the twelfth century, children might have been exposed to texts at home or court if they were wealthy, or in the cathedral schools. First in Latin and later in the vernacular, this literature was most often the Bible, a catechism, or a book of manners.

Early modern (“Renaissance”) European children encountered written literature with their parents or other adults—most often spiritual teachers or schoolmasters.

13th-15th c: secular schools begin to appear (Winchester, Eton)

Prior to the mid-eighteenth

century, children's reading was generally confined to literature intended for

their education and moral edification rather than for their amusement.

Religious works, grammar books, and

"courtesy books" (which offered instruction on proper behavior) were

virtually the only early books directed at children. In these books,

illustration played a relatively minor role, usually consisting of small

woodcut vignettes or engraved frontispieces created by anonymous illustrators.

With the invention of moveable type and printing in the

mid-fifteenth century, the access of all, including children, to literature,

significantly increased,

William Caxton, the first great

English printer, printed Reynard the Fox (1481), The Fables of

Aesop (1484), and Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur (1484)--all

classics enjoyed to this day by children.

WHY were exercise and lesson

books for children among Wm C’s first publications in the 1480s?

·

Lucrative market (children destroy books)

·

Training readers for a lifetime of book-buying:

In the late 15th century

(following the invention in the West of movable type), there was a marked expansion in literacy.

Much of the earliest known text for children consists of TEACHING TOOLS:

HORNBOOKS, BATTLEDORES

·

Hornbooks conveyed the printed word to a wide, new

audience.

·

Hornbooks: These were basically wooden paddles with the

alphabet, vowels and/or the Lord's Prayer printed on a single sheet of

parchment. The sheet was protected from children’s dirty fingers by a very thin

layer of horn (from sheep or goats) that had been softened, boiled, and pressed

into a fine transparent covering.

Hornbooks first appeared in the 1440s and lasted for several centuries

as a tool for teaching reading.

·

Later, the paddle-shaped hornbook would evolve into the

more entertaining battledore: a three-leaf cardboard lesson book with a

variety of printed matter including prayers, verses and lists of vowels and

consonants, often with wood-engraving pictures.

·

The more pictorial battledore, a folded piece of

cardboard with an illustrated alphabet, was named after a traditional game in

which hornbooks were used as paddles. The battledore endured until the

mid-nineteenth century.

Alphabet books exemplify one of

the earliest uses of pictures in instructional books for children.

- Chapbooks: Folded paper booklet

sold by peddlers (chapmen), which appeared in the 1580s. Some told stories

such as Who Killed Cock Robin, and Jack the Giant Killer.

Once they could read, wealthier

English children had access to the Book of Curtesye (1477) and Caxton's Aesop

by 1484. The translation of classical works, for example those

of Ovid, into English during the Renaissance also made these texts available,

not only to Shakespeare and other writers, but to the reading population at

large.

“Puritans” is a collective term that refers to a number of extreme Protestant sects.

A very rudimentary sketch of Protestant history: What is the REFORMATION?

Protestantism established a precarious toehold in England very shortly after Luther's initial protest in 1517, but for many years Protestants remained a tiny minority, frequently persecuted.

- however, widespread discontent both at the extent of corruption within the English Catholic Church and at its lack of spiritual vitality.

- A pervasive anti-clerical attitude on the part of the population as a whole and in Parliament in particular made it possible for Henry VIII to obtain an annulment in 1533 of his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) in the face of papal opposition, and in 1534 the Act of Supremacy transferred papal supremacy over the English Church to the crown.

- In the 1550's, under Edward VI, the English Church became Protestant in doctrine and ritual, and even then it remained traditional in organization.

- Under the Roman Catholic Mary I a politico-religious reaction resulted in the burning at the stake of some prominent Protestants and the exile of many others, which led in turn to a popular association of Catholicism with persecution and Spanish domination.

- When Elizabeth I succeeded to the throne in 1558, however, she restored a moderate Protestantism, codifying the Anglican faith in the Act of Uniformity, the Act of Supremacy, and the Thirty-Nine Articles.

Basic Theological Tenets

Four Latin slogans of the Reformation express some

principal theological concerns of Protestantism, though they are not shared by

all Protestants..

- Solus

Christus (Christ alone):

Only Christ is a mediator between God and man (vs. Catholic confession).

- Sola

scriptura (Scripture alone):

Rejects

the Catholic orthodoxy that Tradition, the teachings of the College of Bishops

united with the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, shares primacy with Scripture

for the handing-on of doctrine: Protestants argue that the Bible is the

only rule of faith. This doctrine is connected with the doctrine of private interpretation of the

bible.

- Sola fide (Faith alone): In contrast to the

Roman Catholic concept of meritorious works of penance and indulgences,

masses for the dead, the treasury of the merits of saints and martyrs, a

ministering priesthood who hears confessions, and purgatory the Protestants

argued that every believer is a priest and obtains reconciliation with God

through faith in Jesus Christ, alone.à ROMANTIC ISOLATION, INDIVIDUALISM

- Sola gratia

(Grace alone).

Against the Roman Catholic view that faith and works necessarily occur

together and that works flow from faith, the Reformers posited that

salvation is a gift from God dispensed through Jesus Christ, regardless of

merit - for no one deserves salvation. The Roman Catholic Church, by

contrast, posits that salvation is not dispensed through Jesus

Christ, but was effected by Jesus Christ, on the Cross at

Calvary.

Note: SCRIPTURE

ALONE:

Protestants are

often considered a people 'of the book', in that

-

they adhere

to the text of the Bible,

-

they grew

out of the enlightenment and universities,

-

they

attracted learned intellectuals, professionals, and skilled tradesmen and

silversmiths,

-

their belief

is more abstracted than ritualized, and

-

the great

dissemination of protestant beliefs occurred with the translation by

Protestants into native tongues from Latin (Greek and Hebrew) with the new

technology of the printing press. VERNACULAR

According to the Protestants, the Bible was the direct word of God. Because of this belief, the Bible was seen as an infallible guide to all life including political, social and economic maters. Protestantism is also suspicious of hierarchy, having relentlessly attacked the priestly cast and the Holy See's authority, and thus is closely associated with the local control and political democratization during the 16th and 17th century.

How does this relate to the question of child literacy?:

FOCUS ON BIBLE + REMOVAL OF PRIESTS AS INTERMEDIARY MAKES LITERACY AN URGENT NECESSITY FOR THE SAKE OF EVERYONE’S SOUL

Some statistics:

- eve of Reformation, approx 2.25 million population, and 400 schools (one school to every 5,625 people whereas in 1864 one school for every 23,750

- 15th-c. Reformation: church schools replaced by private benefactors; increase in vernacular teaching

-

Puritanism in England

Puritanism first emerged as an organized force in England among elements -- Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists, for example -- dissatisfied with the compromises inherent in the religious settlement carried out under Queen Elizabeth I in 1559. The Puritan movement was a broad trend toward a militant, biblically based Calvinistic Protestantism -- with emphasis upon the "purification" of church and society of the remnants of "corrupt" and "unscriptural" "papist" ritual and dogma -- which developed within the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Church of England.

CALVINISM:

French-born theologian and

lawyer John Calvin (1509-1564): Calvin’s theology was presented in the Institutes

of the Christian Religion, published in 1536. Basic tenets included the following

beliefs:

- God is totally and completely sovereign

- All men are totally depraved and deserve eternal damnation. In the beginning, man was created in God’s image, but he destroyed the special relationship with the Creator by tasting the forbidden fruit (Adam’s fall). God’s response was harsh, but just — Adam and Eve and all of their descendants forever were condemned and would bear the mark of original sin.

Original sin is the doctrine that as descendants of Adam, we inherit his

sinfulness, just as we inherit his humanity. In the West, primarily

because of St. Augustine, this concept grew to include the idea that we inherit

Adam’s guilt. Calvin took Augustine’s position to the extreme, teaching that we are totally depraved and without any

natural virtue or worth whatsoever.

- A merciful God, however, took pity on man and sent his Son to redeem some of the damned. No man was deserving of such grace, but God freely offered salvation to an unspecified number (thought to be very small) of sinners. These fortunate individuals were known as the Elect; their fate was determined by God before their births (predestination) and was irreversible.

IF EVERYONE’S FATE WAS

DETERMINED, WHY FOLLOW SUCH STRICT GUIDELINES FOR BEHAVIOUR?

No one knew who was among the saved.

It was commonly accepted by many Calvinists that saintly behavior was a sign

that a person was a member of the elect, but doctrine taught that good conduct

could not “win” salvation for anyone. God had decided that matter long ago. On

the other side of the coin, it was almost universally believed among Calvinists

that a life of dissipation was a sure

sign of damnation. Anxiety

was high in these communities as anguished believers contemplated their fates.

There also was a rather constant and unpleasant interest in one’s neighbors’

activities. People found comfort by observing the moral failures of others and

concluding that they were no doubt among the damned.

The Puritans believed that man must follow the Bible exactly and try to

communicate directly with God. In order to communicate with God there

had to be no distractions from their

religion. Thus, Puritans held to an austere and Spartan life. Puritans

immersed themselves in their work and avoided art, sculpture, poetry, drama or

anything else that might be seen as a distraction. Even home furnishings were

simply made of wood. This routine of hard

work fostered a community that was wealthy and industrious. Since God

was an all knowing and powerful force the puritans saw their wealth as a gift

from God and a sign that they were correct. This sense of special election

characterized the sensibility of the earliest English settlers of America

(Paroussia). The Puritans sought to stamp out anything that might interfere in

the correctness of their way. Non-believers were considered to be in error and

were not tolerated.

Puritan literature for children or, “You’re never too little to go to

Hell”:

The beginning of children's literature (i. e., literature intended specifically for a child audience) lies in the Puritan society of seventeenth-century England. Their purpose in writing for children was to inculcate their religious tenets in their own children through the readings, the focus of which was often the moral preparation of the child for death.

Death reached into all corners of life, striking people of

all ages, not just the old. In the healthiest regions, one child in ten died

during the first year of life. In less healthy areas, like Boston, the figure

was three in ten. Bacterial stomach infections, intestinal worms, epidemic

diseases, contaminated food and water, and neglect and carelessness all

contributed to a society in which 40 percent of children failed to reached

adulthood in the seventeenth century.

Since the mortality rate of children in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was high, the Puritans deemed it imperative that children be instructed so as to prevent them from going to Hell upon their passing out of this life and into the next.

Puritanism placed special emphasis on the individual's need to tend to his or her own salvation

For the Puritans:

· knowledge of the Bible was necessary for every human being

· consequently, the ability to read and to understand the Bible was a principal requirement for Puritan children

· Bible stories were the staple of Puritan children

This week’s readings:

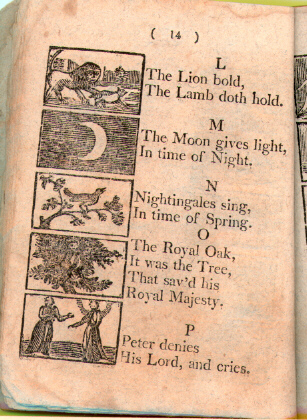

NEW ENGLAND PRIMER—ABCedery: A Puritan publication introducing young children to the alphabet through rhymes

In the 17th and 18th centuries Puritans in England and America dominated thinking about the education of children. The New England Primer (1683) was in use as a reading instruction text longer than any other text in American history—first appearing 1685-90 and continuing in print until 1886.

·

Primers: Small books, often religious in

nature, which appeared in the 16th century. Primers first included

illustrations in the 1650s. The New England Primer was encased in thin oak

sheets covered in coloured paper and printed as early as the 1680s. It was the

staple lesson book for young colonists and early Americans through many

editions and variants. It usually contained prayers and promises for dutiful

children, the anti-Catholic testament of John Rogers, who was the first

Smithfield martyr, a rhymed pictorial alphabet (which often summarized Bible

history) and a Puritan catechism.

·

Examine the example in the course reader: Note

other kinds of teaching along with spelling

A – define Original Sin (central concept for Puritans)

B + H à importance of Bible to Puritans

CDEMNà some examples taken from nature (child’s surroundings)

Fà strictness, direct reference to CHILD’s daily life

à IDLENESS as a particular vice re Puritans

Bible stories: J (job)

Q + X (Esther)

S + U (Samuel, David)

Y - children are not too little to go to Hell

Z - Zacchaeus - pure, a superintendent of customs; a chief tax-gather (publicanus) at Jericho (Luke 19:1-10). "The collection of customs at Jericho, which at this time produced and exported a considerable quantity of balsam, was undoubtedly an important post, and would account for Zacchaeus being a rich man." Being a short man, arrived before the crowd who were later to meet with Jesus Christ as he passed through Jericho on his way to Jerusalem. The tax collector climbed up a sycamore tree so that he might be able to see him. When Christ reached the spot he looked up into the branches, addressed Zacchaeus by name, and told him to come down. Jesus told the man, who was a hated tax collector, that he intended to visit his house. The crowd was shocked that Christ would sully himself by being a guest of a tax collector.

This led to the remarkable interview

recorded by the evangelist, and to the striking parable of the ten pounds (Luke

19:12-27).

O – imperial education (Charles II of Scotland, who tried to reclaim the throne in 1651 and according to legend, took shelter in the branches of an oak to escape the pursuing English army after his forces were defeated. Charles II escaped to exile in France, and after an 11-year period in which no monarch ruled England, was asked by Parliament to return in 1660 and become king; his return is perhaps alluded to by the second crown encircling one of the branches of the stump in this engraving.

JAMES JANEWAY’s “A Token for Children”

Oxford graduate, Nonconformist preacher, died before aged 40

His Token for children is a martyrology: 13 children, holy lives & early deaths

During the Puritan era, John Foxe's martyrology, Actes and Monuments (1563), was considered suitable for children's reading. Its moral message was considered to justify its grisly and detailed accounts of torture and execution practised on early Protestants in England. Children probably listened to others reading from these books rather than read them themselves, but the presence of illustrations in many adult books was certainly further impetus for juveniles actually to open such volumes, read them, and appropriate them.

1672:

James Janeway's A Token for Children, tales of the 'Exemplary Lives and Joyful Deaths of . . . Young Children,' a grimly puritanical and morbid account in the tradition of John Foxe's Actes, still commonly read until about 1790 in both England and the colonies. Firmly based in the concept of original sin, and intended to frighten youth into compliance with strict codes of morality, this book exemplifies an attitude toward children that was punishing and admonitory. The harsh Puritan attitude in choices of reading and in writing for children persisted in some form or another as an undercurrent until the late nineteenth century in England and America.

Read: Example 1 from “A Token for Children”

Compare it to the other assigned readings this week.

According

to Harvey Darton, the Puritans produced the first children's books in England -

that is, books not intended to be used in school, but for leisure reading.

Relying on a dour pedagogy, Janeway's A Token For Children, first published in

1672 and reprinted well into the middle of the nineteenth century, leads its

readers through a gallery of terrifying death-bed scenes. Darton however

says that the woodcuts were clearly expected to have aesthetic value in

showing, for example, a child without terror contemplating a corpse in a

coffin.

A Lamp and no oyl: faith as necessary preparation

Matt 25:1-13 "Then the Kingdom of Heaven will be like ten virgins, who took their lamps, and went out to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish, and five were wise. Those who were foolish, when they took their lamps, took no oil with them, but the wise took oil in their vessels with their lamps. Now while the bridegroom delayed, they all slumbered and slept. But at midnight there was a cry, ‘Behold! The bridegroom is coming! Come out to meet him!’ Then all those virgins arose, and trimmed their lamps. The foolish said to the wise, ‘Give us some of your oil, for our lamps are going out.’ But the wise answered, saying, ‘What if there isn’t enough for us and you? You go rather to those who sell, and buy for yourselves.’ While they went away to buy, the bridegroom came, and those who were ready went in with him to the marriage feast, and the door was shut. Afterward the other virgins also came, saying, ‘Lord, Lord, open to us.’ But he answered, ‘Most assuredly I tell you, I don’t know you.’ Watch therefore, for you don’t know the day nor the hour in which the Son of Man is coming." (web)

A deep, underlying tension characterized the Puritan view of death. On the one hand, in line with a long Christian tradition, the Puritans viewed death as a blessed release from the trials of this world into the joys of everlasting life. At the same time, the Puritans regarded death as God's punishment for human sinfulness and on their deathbeds many New Englanders trembled with fear that they might suffer eternal damnation in Hell.

From their earliest upbringing, Puritans were taught to fear death. Ministers terrorized young children with graphic descriptions of Hell and the horrors of eternal damnation and told them that at the Last Judgment their own parents would testify against them. Fear of death was also inculcated by showing young children corpses and public hangings.

BUNYAN

Illustration seldom accompanied fiction before the nineteenth century, but many other attributes attracted young people to writing for adults. John Bunyan’s illustrated spiritual allegory, Pilgrim's Progress (1678), was extremely popular with children for the next 150 years, evidenced even then by Jo March's tales of struggle with self-mastery in Little Women or Maggie Tulliver’s struggles in The Mill on the Floss. Insofar as the development of strong moral values and mindfulness of God were driving forces of English and American society, this book was made available to children, and, it seems, quite popular.

[Other books of the period appropriated by

children as their own included Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Robinson

Crusoe (1719), both no doubt attractive for their exciting plots and

evocative settings, which stimulated youthful imaginations as much as those of

their elders.]

EXAMINE THE BUNYAN SELECTIONS IN

THE READER: IN WHAT RESPECTS CAN WE SAY THAT ITS INTENT IS TO AMUSE?

John

Bunyan's originally unillustrated Divine Emblems (1686) uses poems to draw

spiritual lessons from homely (and sometimes odd) objects such as a top,

stinking breath, or an hourglass.

DIVINE EMBLEMS:

- analogies are often unexpected, curious

- it takes some mental exercise to actually follow his comparisons: they require a very active engagement

1. effort to comprehend distracts reader from choice to agree with comparison

2. in form, these emblems are a radical appropriation of metaphysical conceits

-

METAPHYSICAL poets, the name given to a diverse group of 17th-century English poets whose work is notable for its ingenious use of intellectual and theological concepts in surprising conceits, strange paradoxes, and far-fetched imagery. The leading metaphysical poet was John Donne. Other poets to whom the label is applied include Andrew Marvell, Abraham Cowley, John Cleveland, and the predominantly religious poets George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, and Richard Crashaw. In the 20th century, T. S. Eliot and others revived their reputation, stressing their quality of wit, in the sense of intellectual strenuousness and flexibility rather than smart humour.

conceit: an unusually far-fetched or elaborate metaphor or simile presenting a surprisingly apt parallel between two apparently dissimilar things or feelings: ‘Griefe is a puddle, and reflects not cleare / Your beauties rayes’ (T. Carew). Under Petrarchan influence, European poetry of the Renaissance cultivated fanciful comparisons and conceits to a high degree of ingenuity, either as the basis for whole poems (notably Donne's ‘The Flea’) or as an incidental decorative device. Poetic conceits are prominent in Elizabethan love sonnets, in metaphysical poetry, and in the French dramatic verse of Corneille and Racine. Conceits often employ the devices of hyperbole, paradox, and oxymoron.

-Bunyan chooses homely objects, familiar to lower/middle classes

Legalist: not simply one knowledgeable of law or a stickler for

legality. In theological terms, a legalist is one who believes in the doctrine

of justification by works.

--vs “Grace alone” doctrine of Protestantism—only God (not good works) can

save a person’s soul.

ISAAC WATTS

Dissenting tutor and pastor, wrote many hymns (e.g. “joy to the world”)

Watts's Divine Songs Attempted in Easy Language for the Use of Children belongs to the history of children's literature. Less forthright than John Bunyan's Book for Boys and Girls (1686) and less fierce than James Janeway's A Token for Children: being an exact account of the conversion, holy and exemplary lives, and joyful deaths of several young children (1671?), the verses reflect common eighteenth-century views of childhood. Reprinted again and again, they held their place in British and American nurseries for close to two hundred years. By the middle of the nineteenth century Watts's songs were so widely known and at once sufficiently old-fashioned that Lewis Carroll could expect an appreciative audience for his Alice in Wonderland (1865) parodies of Watts in "'Tis the Voice of the lobster, I heard him declare" and "How doth the little crocodile."

The verses of Isaac Watts' Divine Songs (1715) were composed of easy, often pretty lines, which gave more emphasis to praise and thankfulness as suitable religious emotions for a child, and displayed a gentleness new for his time, though the Puritan emphasis on the innate wickedness of children is still evident.

(Another advance in the struggle between

instruction and delight)

Watts's version of literary morality and religion is attuned to contemporary psychology, which in its historical turn was indebted to the spiritual self-consciousness of the Puritans. The promotion of virtue depended on the poet's capacity to move his reader, to inspire feelings conducive to virtue and piety. This feature is characteristic of the literature not of romance but of sensibility. Religious feeling was good in itself, a hallmark of piety, and good as well as a motive force, encouraging virtuous living.

The new element lightens the poet's heavy burden of responsibility and Renders an honest enjoyment of literature legitimate. Indeed, Watts's love of literature rings in the language of his protest against the immorality of contemporary literary practice. Joy in words was not new to religion; good preaching demands verbal wit and a rhetorical ear. The understanding of how imaginative literature might function as a means to a devotional end was, however, distinct from traditional understanding. Virtuous poetry elevated thoughts and inspired piety.

Note the first person pronoun in some of our Watts selections: these poems are meant to be performed by children. (See Alice in Wonderland)

In this respect, these poems resemble Watts’s hymns.

As congregational song, hymns were texts for amateur public performance, loaded with evangelical importance and theological authority, they were severely limited to the three meters of psalmody and to common Christian language and understanding. Indeed, hymns depended for their success on real pleasures, on their value as entertainment. Singers, quite ordinary singers, perhaps distracted by worldly concerns, were to be caught up in the "divine delight" of a poetry that far surpassed secular enjoyments. This essential delight took highly visual, even dramatic, form akin to the stained-glass windows and liturgical drama of non-Calvinist traditions.

Features of Watts’s songs:

- Gently softens the Christian message

- Conscious desire to praise

- Deliberate effort to divert, amuse and entertain

- Children are still miniature adults—god-fearing, sin-obsessed

- Become memory exercises for children to performà parodied in Alice

Watts's preface "To all that are concerned in the Education of Children" advocates Christian educational poetry as pleasurable, memorable, substantial, and devotionally useful.

- He declares the nonsectarian content of the songs, in which "the Children of high and low Degree, of the Church of England or Dissenters, baptized in Infancy or not, may all join together."

- He has "endeavoured to sink the Language to the Level of a Child's Understanding, and yet to keep it (if possible) above Contempt."

- To facilitate singing, the verse forms are those of the metrical psalter. Given these constraints, the songs in themselves are hardly remarkable as lyric poetry.

-

Simple and straightforward in

form and content, they range from little songs of praise to a concise scheme of

redemption, Adam through the Judgment, in eight stanzas. Cautionary songs warn

against lying, quarrelling, scoffing, swearing, idleness, mischief, keeping

evil company, and having pride in clothes. In others, love between brothers and

sisters and filial obedience are recommended.

-

The supposition behind his

method was that the individual was

intrinsically capable of virtue or piety. He or she had the resources, which only needed focus and

cultivation. This confidence in human ameliorability is apparently at

odds with the conviction of the worm-like baseness of humankind. The depravity

of humanity, an item of Watts's faith, is evidently incompatible with his

poetic intent and method.

SHERWOOD AND THE SUNDAY SCHOOLS MOVEMENT

Starting in 1807, poor excluded from schools for mid/upper as a matter of policy: previously, spaces would be found for exceptionally bright poor students.

Along with day schools, Sunday schools fill this gap: --Sunday schools teach poor children and adults to read (Scripture)

NB: Sherwood was a plagiarist and bowdleriser (the closing hymn in our selection is stolen from Watts): selective idea of sin, different ideology from ours.

Evangelicals (19th-c)à missionary movement, Post Colonial context

Evangelical, a term literally meaning "of or pertaining to the Gospel," was employed from the eighteenth century on to designate the school of theology adhered to by those Protestants who believed that the essence of the Gospel lay in the doctrine of salvation by faith in the death of Christ, which atoned for man's sins. Evangelicalism stressed the reality of the "inner life," insisted on the total depravity of humanity (a consequence of the Fall) and on the importance of the individual's personal relationship with God and Savior. They put particular emphasis on faith, denying that either good works or the sacraments (which they perceived as being merely symbolic) possessed any salvational efficacy. Evangelicals, too, denied that ordination imparted any supernatural gifts, and upheld the sole authority of the Bible in matters of doctrine. The term came into general use in England at the time of the Methodist revival under Wesley and Whitefield, which had its roots in Calvinism and which, with its emphasis on emotion and mysticism in the spiritual realm, was itself in part a reaction against the "rational" Deism of the earlier eighteenth century. Early in the nineteenth century the terms "Evangelical" and " Methodist" were used indiscriminately by opponents of the movement, who accused its adherents of fanaticism and puritanical disapproval of social pleasures. The Evangelical branch of the Anglican Church coincided very nearly with the "Low Church" party.

The Evangelical party of the Church of England (the established church) flourished from 1789 to 1850, and during that time increasingly dominated many aspects of English life and, with its dissenting or nonconformist allies, was responsible for many of the attitudes today thought of as "Victorian." These heirs of the seventeenth-century Puritans believed:

- that human beings are corrupt and need Christ to save them-- thus the emphasis upon puritanical morality and rigidity;

- that the church hierarchy and church ritual are not as crucial to individual salvation as a personal conversion based on an emotional, imaginative comprehension of both one's own innate depravity and Christ's redeeming sacrifice-- thus the emphasis upon an essentially Romantic conception of religion that stressed imagination, intensity, and emotion, and also upon the Bible, which could provide such imaginative experience of the truths of religion. What effects would you guess Evangelicalism had upon fiction? Poetry?

-

that converted believers must

demonstrate their spirituality by working for others-- thus Evangelical zeal in

missionary work, Bible societies, anti-slavery movements, and many social

causes;

- that the converted will be persecuted and that such persecution indicates the holiness of the believer (since Satan has much power over man and his world; see 1 above)-- thus Evangelical willingness to speak on behalf of unpopular causes and, rather annoyingly to many contemporaries, to take any political, social, or religious opposition as a martyrdom;

- that God arranged history and the Bible, of which every word was held to be literally true, according to elaborate codes and signals, particularly in the form of typology, an elaborate system of foreshadowings (or anticipations) of Christ in the Old Testament-- thus Evangelical emphasis upon complex integrated symbolism and upon elaborate interpretation of everything from natural phenomena and contemporary history to works of art and literature

Sunday Schools: aimed to “reform manners, implant religious knowledge, and encourage proper observance of the Sabbath” (Sarah Trimmer).

Although often bigoted (racially and socially), these reformers advocated important improvements such as abolition of slavery, child-labour legislation.

Their stories are accessible, emotionally satisfying, and highly moral (therefore approved by parents)

Note:

- White is the traditional colour for children’s funerals. Although Sherwood gives a full definition of “hearse,” she forgets to explain this!

- Why does Augusta deserve her fate?

- How are gender stereotypes expressed here?

- What are the class connotations of the story?

TURNER:

The religious context has been removed from the cautionary tale

Completely domestic context

Helen the giddy girl is ONLY disobeying her mother

Giddiness is a mental state, not a spiritual one

Her mother’s advice is completely practical

HOFFMAN

Note the full title of Struwwelpeter.

How has the Cautionary Tale has been turned into nonsense?

What are the signals that let us know that “Poor Pauline’s” predicament is funny?