Useful links

Historical timeline of the United Church of Canada

"The day the United Church was born," from the Observer, June 2000

United Church Archives, "Celebrating our Heritage"

A few back issues of Touchstone

Print bibliography

S.D. Chown, The Story of Church Union in Canada (1930)

N.K. Clifford, "Church Union and Western Canada," in Prairie Spirit: Perspectives on the Heritage of the United Church of Canada in the West, ed. Dennis L. Butcher et al. (1985)

N.K. Clifford, The Resistance to Church Union in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1985)

Kenneth H. Cousland, "Bibliography of Church Union in Canada," in American Theological Library Association Summary of Proceedings, 1959:89-101

Edgar F. File, "A Sociological Analysis of Church Union in Canada," Ph.D. thesis, Boston University (1962)

John Webster Grant, The Canadian Experience of Church Union (1967)

B. Kiesekamp, "Community and Faith: The Intellectual and Ideological Bases of the Church Union Movement in Victorian Canada" Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto (1974)

G. Morrison, "The United Church of Canada, Ecumenical or Economical Necessity," B.D. thesis, Emmanuel College (1956)

E. Lloyd Morrow, Church Union in Canada: Its History, Motives, Doctrine and Government (1923)

George Pidgeon, The United Church of Canada: The Story of the Union (1950)

Margaret Ray, "The Collection on Church Union in

the Archives of Victoria University,"

The Bulletin 3 (1950)

Neil Semple, The Lord's Dominion: The History of Canadian Methodism (chapter 16)

C.E. Silcox, Church Union in Canada: Its Causes and Consequences (1933)

T.R. Millman, "The Conference on Christian Unity, 1889," in Canadian Journal of Theology 3 (1957): 165-174

N.K. Clifford, "The Origins of the Church Union Controversy", JCCHS 18 (1976 ) 34-52 [1902-1911 period]

Richard Ruggle, "Herbert Symonds and Christian Unity", JCCHS 18 (1976) 53-83

Alan Farris, "The Fathers of 1925"

Archibald, Tim F. "Remaining Faithful: Church Union 1925 in the Presbytery of Pictou." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XV (1990): 20-38

Campbell, Douglas F. "Presbyterians and the Canadian Church Union: A Study in Social Stratification." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XVI (1991): 1-32

Clifford, N. Keith. "The Origins of the Church Union Controversy." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers II (1976): 49-71.

________. "Urbanization and the Church Union Controversy." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers V (1979): 31-52.

Corbett, Donald J. M. "The Legal Problems of the Canadian Church Union of 1925." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers V (1979): 53-67.

Cossar, Bruce. "Church Union in Kingston." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XXV (2000): 1-13.

Dunn, Zander. "'the Great Divorce and What Happened to the Children.' an Investigation Concering the Effects of the 'Dis-Union' of 1925 on the Foreign Mission Fields of the Presbyterian Church in Canada." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers III (1977): 58-96.

Grant, John Webster. "1925 and 'All That'." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XXVI (2001): 38-46.

Millar, Michael. "'We, Ministers and Elders,...Hereby Dissent." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XXI (1996): 34-60.

Prideaux, Brian. "'Call Me and an Anti-Disunionist': D.R. Drummond and the Federalist Option in the 1925 Church Union Debate." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XVI (1991): 33-58.

Redmond, Chris. "John Somerville in the General Assembly: Case Study of a Presbyterian Unionist." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers XIII (1988): 31-47.

Anglicans and ecumenism before 1925

Anglicans were the first to propose a church union across denominational lines, but quickly developed cold feet. In 1888 the Lambeth Conference (a decennial meeting of Anglican bishops worldwide, meeting in London) had commended "home reunion" (church union). On that occasion it stated a fourfold basis for ecumenical discussion, which has since been called "The Lambeth Quadrilateral". The following year, taking the cue, the Anglican provincial synod of Canada invited its mainstream Protestant partners into exploratory discussions, and Methodists and Presbyterians did indeed respond. But Methodists proved cool to the idea, and Presbyterians wanted a clearer statement of doctrine than Anglicans were inclined to allow.

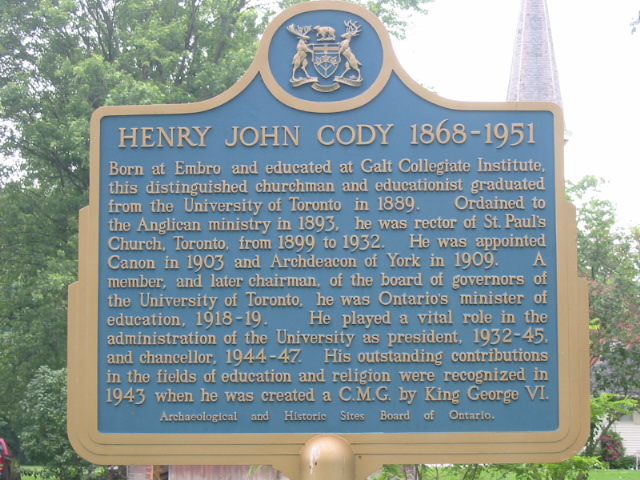

The most energetic Anglican

proponent of church union was Herbert Symond, latterly of Montreal. (An

article about him by Richard Ruggle is referenced in the left-hand column.)

Another was Henry J. Cody, the influential rector of the large and wealthy

St. Paul's, Bloor Street, in Toronto. But most bishops were opposed, and

without their support no progress could be made. Perhaps the mellowest

of the episcopal opponents was Bishop John Cragg Farthing of Montreal,

who not only protected Symond, but who also endorsed what was up to that

time the most advanced ecumenical theological institution in Canada, if

not North America, the Joint Board (founded in 1912) of the four theological

colleges (Anglican, Congregational, Presbyterian, Wesleyan Methodist)

that were affiliated with McGill University.

The most energetic Anglican

proponent of church union was Herbert Symond, latterly of Montreal. (An

article about him by Richard Ruggle is referenced in the left-hand column.)

Another was Henry J. Cody, the influential rector of the large and wealthy

St. Paul's, Bloor Street, in Toronto. But most bishops were opposed, and

without their support no progress could be made. Perhaps the mellowest

of the episcopal opponents was Bishop John Cragg Farthing of Montreal,

who not only protected Symond, but who also endorsed what was up to that

time the most advanced ecumenical theological institution in Canada, if

not North America, the Joint Board (founded in 1912) of the four theological

colleges (Anglican, Congregational, Presbyterian, Wesleyan Methodist)

that were affiliated with McGill University.

Anglicans were cool to church union for several reasons. First and foremost was that they insisted on a strong episcopal authority, which they couldn't expect most Methodists or any Presbyterians to accept. Another was that they didn't want to jeopardize their close relationship with the mother Church of England. Thus the kind of Canadian nationalism which helped energize church union among other Methodists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists was actually something of a handicap among Anglicans. Another was the probably accurate perception that Anglican proponents of ecumenism were also theological liberals, as Symonds and Cody were. The residual conflicts between "high-church" and "low-church" Anglicans also figured, with the "high church" wanting to protect the integrity of Anglican ecclesiastical order against the toxic dangers of dissenting Protestantism. A final factor was what John Webster Grant has called "an almost incredible degree of mutual misunderstanding" between Anglicans and their prospective ecumenical partners in their correspondence of 1908-1909 (Church in the Canadian Era, p. 112, footnote 52).

The founding of the United Church of Canada

The following six sections are a draft version of an article which Phyllis Airhart has since published in Routledge's Encyclopedia of Protestantism (s.v. "United Church of Canada").

The founding of the

United Church of Canada stands as one of the most important and controversial

episodes in Canadian religious history. The inaugural ceremony in Toronto

on 10 June 1925 brought together the Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland

and Bermuda). the Congregational Union of Canada, and all but a third

of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. A number of local congregations

already operating as union churches, most of them in western Canada, were

also formally received into the new organization. The United Church of

Canada began with approximately 8,000 congregations, 600,000 members and

3,800 ministers. Since then it has remained the largest Protestant denomination

in Canada.

The founding of the

United Church of Canada stands as one of the most important and controversial

episodes in Canadian religious history. The inaugural ceremony in Toronto

on 10 June 1925 brought together the Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland

and Bermuda). the Congregational Union of Canada, and all but a third

of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. A number of local congregations

already operating as union churches, most of them in western Canada, were

also formally received into the new organization. The United Church of

Canada began with approximately 8,000 congregations, 600,000 members and

3,800 ministers. Since then it has remained the largest Protestant denomination

in Canada.

By bringing together Methodism and two varieties of the Reformed tradition

(Presbyterians and Congregationalists), the United Church of Canada was

the first modern experiment in union across confessional lines in western

Christianity. Despite much enthusiasm for Christian unity in the nineteenth

and twentieth centuries, this "organic" type of union was rarely

consummated in other places. However, it was a model well suited to the

Canadian

context. Divisions were easier to overcome than in many other countries

since the uniting parties had already succeeded in consolidating along

denominational lines by the time serious union discussions were underway.

The prospect of creating a church that would relate in a special way to

the young nation of Canada, which had been confederated in 1867, was an

alluring one at a time when national identity was fragile. Church leaders

also saw union as the most effective way to take care of the religious

needs of new immigrants who were arriving in large numbers. The west was

a particular challenge; attempts to reach the new settlements in the prairies

stretched competing denominational resources.

Canadian

context. Divisions were easier to overcome than in many other countries

since the uniting parties had already succeeded in consolidating along

denominational lines by the time serious union discussions were underway.

The prospect of creating a church that would relate in a special way to

the young nation of Canada, which had been confederated in 1867, was an

alluring one at a time when national identity was fragile. Church leaders

also saw union as the most effective way to take care of the religious

needs of new immigrants who were arriving in large numbers. The west was

a particular challenge; attempts to reach the new settlements in the prairies

stretched competing denominational resources.

Even in these propitious circumstances, church union was accomplished only after a long and bitter round of negotiations drawn out over a period of nearly three decades. After hearing exhortations from denominational leaders urging greater cooperation for over a decade, representatives of the three traditions begin work on a "Basis of Union" in 1904. Four years later it was ready for consideration by the courts of the three churches and their members.

Support for union among Methodists and Congregationalists was solid and approval quickly secured, with only Methodists in Newfoundland voting to reject it. The story was different in the Presbyterian Church, which saw the organization of an effective resistance movement to oppose union at the local level after the General Assembly approved it. Under the provisions of legislation passed in federal parliament in 1924, a congregational vote was held in each Presbyterian congregation to determine whether it would join the new church. A commission was appointed to distribute the general denominational assets. Dissenting congregations who rejected the recommendation of the General Assembly to enter union thus continued to hold property as the "Presbyterian Church in Canada." The issue of whether the dissenters could legally carry that name was contested until it was resolved by the Supreme Court of Canada in their favor in 1939.

Religious life in Canada was thus left less united than the founders had hoped. Their anticipation of the 1925 union as the first of more to follow has also gone largely unrealized, although the Evangelical United Brethren became part of the United Church of Canada in 1968. Over the years other denominations, notably the Anglicans, Baptists and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), have considered amalgamation, but no such discussions are currently underway. Particularly disappointing was the termination in 1975 of discussions with the Anglicans to create the Church of Christ in Canada.

However, the United Churchof Canada remains a leader in ecumenical activity, with mutual recognition of ministries emerging as the main expression of its commitment to Christian unity. It provides leadership in ecumenical affairs nationally as well as at the international level. It was instrumental in organizing the Canadian Council of Churches in 1944 and was a charter member of the World Council of Churches in 1948. It retains its relationship with the World Alliance of Reformed Churches and the World Methodist Council.

Characteristics of the United Church

During the controversy over church union, those who objected to forming the United Church of Canada claimed that it was liberal to the point of being apostate and more interested in politics than spirituality. Such charges obscured the importance of its evangelical heritage and the commitment to transformation of both individuals and institutions which was central to the evangelical piety of the founding traditions.

The articles of faith adopted in 1925 as part of the Basis of Union reflected the liberal evangelical perspective of its early twentieth-century formulation. Those who prepared it regarded it as a statement of the "common faith" of the uniting denominations and an articulation of the theological convictions of their own generation. Since formulation of a confession of faith in meaningful language for the times was viewed as the ongoing task of each generation, a committee soon began work on the "Statement of Faith" approved in 1940. What is referred to as the "New Creed" has been in use since 1968 with a few modifications over the years. In response to calls for a new confession of faith, the General Council requested in 2000 that the Committee on Theology and Faith begin work on a document which would honor the church's theological diversity and acknowledge its place in a pluralistic world.

The church also proudly celebrates the influence of the social gospel which was evidenced in its impulse to serve as the "conscience of the nation." It has claimed that aspect of its heritage when taking positions on political and social issues viewed at the time as risky or controversial. Its theological schools and congregations have been receptive to biblical criticism, an openness reflected in preaching and educational projects, notably the "New Curriculum" introduced in the 1960s. Some decisions, such as its positions on remarriage of divorced persons in the early 1960s and ordination of gay and lesbian persons in 1988, generated controversy at the time but later have been adopted with less fanfare by other denominations. It continues to study, issue statements, and make efforts to influence governments and other agencies responsible for shaping policy on such issues as abortion, capital punishment, racial equality, land use, refugees, and poverty.

Being the "conscience of the nation" has not always been a comfortable role. The apology to native peoples which the denomination issued in 1986 was accompanied by an experiment to provide their congregations with greater autonomy and responsibility through creation of the All Native Circle Conference in 1988. The church continues to wrestle with the financial and moral implications of the residential schools set up and supported by those who saw assimilation of native children to mainstream culture as their best hope of inclusion in modern industrial society. This proved to be an experiment with tragic consequences for many native families. The church's involvement in helping the federal government to operate the schools was an entanglement for which the General Council apologized in 1998.

Leadership in the United Church

The church's

leaders have set the tone for its work from the outset. One of the memorable

moments of the first General Council in 1925 came when former Methodist

General Superintendent S.D. Chown, the architect of church union and considered

the leading candidate for the moderator's position, stepped aside in favor

of George Pidgeon (pictured right), the principal spokesperson

for the uniting Presbyterians. The position of moderator has since recognized

the gifts of distinguished men and women in the church, while providing

the church with a way to highlight its mission and ideals in the selection.

The church's

leaders have set the tone for its work from the outset. One of the memorable

moments of the first General Council in 1925 came when former Methodist

General Superintendent S.D. Chown, the architect of church union and considered

the leading candidate for the moderator's position, stepped aside in favor

of George Pidgeon (pictured right), the principal spokesperson

for the uniting Presbyterians. The position of moderator has since recognized

the gifts of distinguished men and women in the church, while providing

the church with a way to highlight its mission and ideals in the selection.

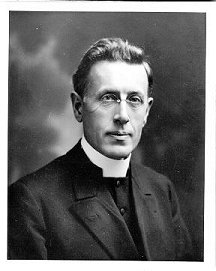

Other executive

positions have provided the incumbent with opportunities to put the social

and spiritual agenda of the church before the public. James Endicott,

a missionary to China, caught the attention of the public and gained notoriety

as a "public enemy" for his outspoken support for the Communist

Revolution. In the early years, the secretaries of the Board of Evangelism

and Social Service were particularly effective in using press and pulpit.

In the 1950s James R. Mutchmor opposed the three B's: "betting, beer

and bingo" while in the 1960s Ray Hord's condemnation of the Vietnam

War and support for "draft-dodgers" created headlines. Medical

missionary Robert McClure was an effective public spokesperson for overseas

work and in 1968 became the first lay member to serve as moderator.

Other executive

positions have provided the incumbent with opportunities to put the social

and spiritual agenda of the church before the public. James Endicott,

a missionary to China, caught the attention of the public and gained notoriety

as a "public enemy" for his outspoken support for the Communist

Revolution. In the early years, the secretaries of the Board of Evangelism

and Social Service were particularly effective in using press and pulpit.

In the 1950s James R. Mutchmor opposed the three B's: "betting, beer

and bingo" while in the 1960s Ray Hord's condemnation of the Vietnam

War and support for "draft-dodgers" created headlines. Medical

missionary Robert McClure was an effective public spokesperson for overseas

work and in 1968 became the first lay member to serve as moderator.

The United

Churchof Canada was the first denomination in Canada to ordain women (Lydia

Gruchy in 1936, pictured right) and has since elected women

to other prominent positions. In 1980, Lois

Wilson (pictured below, left) became the first woman to serve

as moderator. In 1994 Virginia Coleman was elected as Secretary of General

Council, the denomination's chief administrative office.

The United

Churchof Canada was the first denomination in Canada to ordain women (Lydia

Gruchy in 1936, pictured right) and has since elected women

to other prominent positions. In 1980, Lois

Wilson (pictured below, left) became the first woman to serve

as moderator. In 1994 Virginia Coleman was elected as Secretary of General

Council, the denomination's chief administrative office.

Structure, Key Organizations, and Publications

The United

Church of Canada is organized at four levels: local congregations or pastoral

charges; 91 district Presbyteries which exercise oversight of 20-50 pastoral

charges; 13 regional Conferences which meet annually; and the national

General Council which meets on a biennial or triennial basis to make decisions

in areas of program and administration concerning the whole church.

The United

Church of Canada is organized at four levels: local congregations or pastoral

charges; 91 district Presbyteries which exercise oversight of 20-50 pastoral

charges; 13 regional Conferences which meet annually; and the national

General Council which meets on a biennial or triennial basis to make decisions

in areas of program and administration concerning the whole church.

The work of the divisions of General Council is supported through contributions

from local congregations through the Mission and Service Fund. The four-court

structure of the church was reviewed in 2000. The General Council approved

a restructuring plan which will be voted on by all presbyteries and pastoral

charges and the results considered by the next General Council. The proposed

changes would combine the responsibilities and powers of current presbyteries

and Conferences into a single entity.

The United Church of Canada relates to a variety of educational institutions

which includes thirteen theological schools and programs, five educational

centers, and six liberal arts colleges and universities. The educational

work of the denomination is also carried on in congregations through organizations

for children, youth, and

gender-specific associations for adults. Centralized coordination at the

national level was evident in the 1940s and 50s in organizations such

as the Canadian Girls in Training which began 1915 and continued after

union (shown above: Kitimat (B.C.) First United Church CGIT, 1960),

Trail Rangers for boys 12 to 14, Tuxis Boys for 15 and up, an Older Boys

Parliament, and the Young People's Society. "As One That Serves"

was an idea for a Methodist men's club in Vancouver just before church

union which spread across Canada. At the time of church union, the voluntary

societies which women had organized in the nineteenth century emerged

as the Woman's Missionary Society and the Woman's Association which in

turn amalgamated in 1962 as the United Church Women.

for children, youth, and

gender-specific associations for adults. Centralized coordination at the

national level was evident in the 1940s and 50s in organizations such

as the Canadian Girls in Training which began 1915 and continued after

union (shown above: Kitimat (B.C.) First United Church CGIT, 1960),

Trail Rangers for boys 12 to 14, Tuxis Boys for 15 and up, an Older Boys

Parliament, and the Young People's Society. "As One That Serves"

was an idea for a Methodist men's club in Vancouver just before church

union which spread across Canada. At the time of church union, the voluntary

societies which women had organized in the nineteenth century emerged

as the Woman's Missionary Society and the Woman's Association which in

turn amalgamated in 1962 as the United Church Women.

Since the 1970s the church's special-purpose groups have experienced loss of membership and dwindling support for volunteer activities. This has spurred a number of efforts to loosen national coordinating structures to see what new forms emerge. The most striking move was a decision in 2000 to adopt the name "Women of the United Church of Canada" to refer collectively to the church's programming for women. Whereas the focus of United Church Women was fundraising, hospitality and study, the new organization will incorporate UCW units as well as spirituality and support groups that have emerged as alternatives.

The

publication of The Hymnary (1930) and The Book of Common Order

(1932) gave definition to the worship traditions of uniting congregations.

A new Service Book was published 1969. The Hymn Book, published

jointly with the Anglican Church of Canada in 1971, was followed a generation

later by Voices United 1996, a work which has received a more enthusiastic

reception than its predecessor. The United Church Observer is the

official publication of the denomination.

The

publication of The Hymnary (1930) and The Book of Common Order

(1932) gave definition to the worship traditions of uniting congregations.

A new Service Book was published 1969. The Hymn Book, published

jointly with the Anglican Church of Canada in 1971, was followed a generation

later by Voices United 1996, a work which has received a more enthusiastic

reception than its predecessor. The United Church Observer is the

official publication of the denomination.

Geography

The United Church of Canada operates primarily in Canada, although a few Methodist congregations in Bermuda comprise a presbytery which relates to Maritime Conference. The denomination has also been involved in overseas missions since its founding. The churches which joined to form the denomination had established missions in such places as Angola, China, India, Japan, Korea and Trinidad. This work continued and at first expanded after union. The largest mission in the whole of China before the Communist Revolution was its West China Mission. Reflecting a changed concept of world outreach from "foreign missions" to an emphasis on working with ecumenical partners around the world, the United Church of Canada now works under the direction of indigenous ecumenical partners in overseas countries at the request of churches and agencies, providing funding and personnel for projects.

Expansion or Decline?

Since its founding the United Church of Canada has followed a trajectory similar to mainstream churches in the United States during the same period: it enjoyed something of the status of a voluntary (though never legal) establishment for the first few decades; suffered a decline in membership and financial resources during the depression years; experienced a post-war revival of religious interest which included new congregational development in the suburbs; and has recently seen lower rates of membership and participation with the first reported loss of membership in 1966. In 1999 it reported the number of confirmed members as 668,549.