1867-1893

The Evolution of National Structures

Useful links

As you begin reading the primary source documents for our course book, you'll find it VERY HELPFUL to read this discussion about reading historical documents

A slide on the Presbyterian union of 1875, from the PCC Archives

An address reflecting on Methodist church history in Manitoba, 1944

Some Presbyterian history through the lens of Knox Presbyterian Church, Toronto

Gerry Ediger's PDF lecture notes on Christianity in Canada 1876-1925

Legislation for Methodist union in 1884, together with the Basis of Union (1884) as Appendix 1,

Print bibliography

- Moir, Enduring Witness

John Moir "Who Pays the Piper", from Early Presbyterianism in Canada - Mark Noll, The Old Religion in a New World, chapter 1

- Johnston, John A. "The Canadian Presbyterian Union of 1875." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers I (1975): 61-106.

- Vaudry, Richard W. "'for Christ's Kingdom and Crown': The Evangelical Party in the Church of Scotland and the Problem of Church-State Relations, 1829-1843." The Canadian Society of Presbyterian History Papers VII (1981): 21-41.

The creation of the dominion of Canada in 1867, and the growing sense that sooner or later it would extend from sea to sea, motivated the denominations to build national church organizations. For Anglicans this "simply" meant (it wasn't so simple in practice) joining together the Anglican organizational structures that already existed in different parts of the country. For Methodists and Presbyterians there were also schisms and splits that had to be healed.

John Moir, "The search for a Christian Canada"

John Moir is an eminent

Canadian historian, now retired, who taught for many years at Scarborough

College of the University of Toronto. He is also a Presbyterian who has

taken a particular interest in the history of Christianity in Canada.

(He's seen here with the Presbyterian moderator at the 2003 General Assembly.)

John Moir is an eminent

Canadian historian, now retired, who taught for many years at Scarborough

College of the University of Toronto. He is also a Presbyterian who has

taken a particular interest in the history of Christianity in Canada.

(He's seen here with the Presbyterian moderator at the 2003 General Assembly.)

In this article, Moir begins by noting that the European powers that colonized the new world typically tried to replicate their own religious institutions. Thus after the British acquired Canada in 1763, they looked for ways to establish the Church of England. But for various reasons they had to accommodate a second, Roman Catholic establishment in 1774. And then in 1848 the Reform government invited other churches into a "hydra-headed religious establishment." This desire for an established Christianity was part of the search for a Christian Canada. Now, establishmentarian ideals seemed to die when the clergy reserves were secularized in 1854, but Moir says that the idea of a "Christian Canada" remained very much alive. In the era of Confederation it took the form of developing "a consensus about what constituted a righteous nation."

Here are some questions for you to consider as you read this article.

When nineteenth-century Protestants referred to a "Christian Canada", what kind of a country did they have in mind? What transitions in the notion of a "Christian Canada" are indicated in Moir's article? How does he account for the transitions?

In what ways did the pattern of establishment that was typical of European churches continue to influence religion in Canada after "disestablishment"?

What is Moir referring to when he uses the term "national church"? Why was a "national church" thought to be a necessity?

What were the problems facing the new nation of Canada? Were the churches "co-opted" into supporting a political agenda that distracted them from the message of the Gospel?

As you look at the mission agenda of the Protestant churches, what do they assume the churches "competent" to do? What is their mission in Canada? What is their view of Canada as a "mission field"?

Was Christianity important to the state because it gave Canadians something to which they could assimilate in the absence of a distinctive national identity? How did the churches contribute to creating a distinctive Canadian culture?

Who is missing from the picture of a "Christian Canada"? How are differences (including religious traditions) handled?

Moir asks (p. 23), "Was there ever a Christian Canada, or was it an impossible dream?" How would you answer?

Presbyterians

Roots of the Presbyterian Church in Canada

Introduction

The Presbyterian Church in Canada was created in 1875 when four separate

Presbyterian denominations united.  (George

M. Grant, a Presbyterian minister in Halifax and later principal of

Queen's University in Kingston, had worked for Presbyterian union in the

Maritimes in 1868.) What may be surprising to Canadian Presbyterians today

was that these denominations weren't merely regional, but represented

distinct understandings of what it meant to be a Presbyterian. Each of

the two major regions (the Maritimes, the old province of Canada) of the

new Dominion of Canada (itself created in 1867), had one Presbyterian

tradition linked to the established Church of Scotland, and another

one comprised of an amalgamation of various groups which had broken

away from the Church of Scotland. (To a large extent these divisions had

resulted from "church/state" controversies — but that term

is somewhat misleading. Often what had been at issue in these divisions

was who got to choose the minister for a local congregation, rather than

what we might think of today as church/state issues, such as prayer in

public schools or the role of religion in politics.)

(George

M. Grant, a Presbyterian minister in Halifax and later principal of

Queen's University in Kingston, had worked for Presbyterian union in the

Maritimes in 1868.) What may be surprising to Canadian Presbyterians today

was that these denominations weren't merely regional, but represented

distinct understandings of what it meant to be a Presbyterian. Each of

the two major regions (the Maritimes, the old province of Canada) of the

new Dominion of Canada (itself created in 1867), had one Presbyterian

tradition linked to the established Church of Scotland, and another

one comprised of an amalgamation of various groups which had broken

away from the Church of Scotland. (To a large extent these divisions had

resulted from "church/state" controversies — but that term

is somewhat misleading. Often what had been at issue in these divisions

was who got to choose the minister for a local congregation, rather than

what we might think of today as church/state issues, such as prayer in

public schools or the role of religion in politics.)

This subject continues to be one of the most difficult in our understanding of the development of the Canadian Presbyterian tradition. A very brief description of some of these traditions is offered:

1. Church of Scotland

After the Reformation

parliament in Scotland the official or established church was a Reformed

church in the Calvinist tradition. What was not agreed upon was how that

church was to be governed — by bishops, or by presbyteries. It was

not until 1690 that the Presbyterian form of government became once and

for all the official polity of the Church of Scotland.

After the Reformation

parliament in Scotland the official or established church was a Reformed

church in the Calvinist tradition. What was not agreed upon was how that

church was to be governed — by bishops, or by presbyteries. It was

not until 1690 that the Presbyterian form of government became once and

for all the official polity of the Church of Scotland.

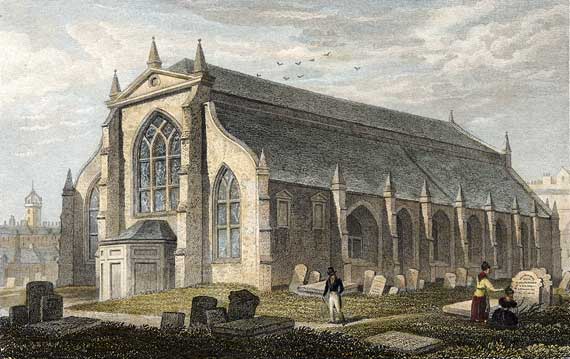

2. Covenanters

The

National Covenant of 1638, pictured below to the right, was signed

by thousands in the churchyard of Greyfriars Church (a quarter mile from

Edinburgh Castle), pictured above. The covenanting tradition never accepted

the Restoration settlement in Scotland in 1660, or later developments.

Covenanters therefore broke off from the main body of the Kirk. They were

persecuted in Scotland, and many went overseas, including British North

America. The covenanting tradition has been independent and has not been

part of the various unions that created the Presbyterian Church  in

Canada.

in

Canada.

3. Secessionists

Secessionists were those who left the Church of Scotland in a series of divisions in the 18th century. Secessionists continued to disagree among themselves, leading to further divisions, and then reunifications. Secessionist Presbyterian ministers were prominent among the early missionaries to Canada both due to their missionary zeal and the reality that they could not legally obtain a parish in Scotland.

4. Free Church

The Free Church grew out of a particular 19th-century split within the Church of Scotland. As many of the ministers sent to Canada from the Church of Scotland had been supported by the Glasgow Colonial Society, whose directors left the Church of Scotland for the Free Church, Scottish divisions resulted in a split within the colonial Canadian church.

5. Other Presbyterians

This "miscellaneous" group is often overlooked. Presbyterians from the United States, with a distinct history and a strong revivalist tendency, established congregations in Upper Canada and other parts of what would become Canada. Irish Presbyterians are almost overlooked in many of our discussions. While we will not focus on these groups, it is important to recognize how diverse the pioneer situation was.

Methodists

Methodists in Canada took a major step towards consolidation in 1874 when the Wesleyans and New Connection Methodists formed the Methodist Church of Canada. In 1884 they joined the Primitive Methodists, Bible Christians, and the Methodist Episcopal churches to form the Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland, and Bermuda — often shortened to "CNB"). Some of the pre-union Methodist bodies had been organized only in Ontario. Now together they formed the largest Protestant denomination in late nineteenth-century Canada.

The Methodist Church has sometimes been described as the most "Canadian"

of the various Protestant denominations in the years after Confederation.

While no more enthusiastic at the time than other churches about the prospects

of Confederation, after 1867 they responded with enthusiasm to the challenge

of meeting the religious needs of those who were settling in the new communities

that followed the construction of a national railway system. Differences

of theology and polity paled alongside the mission  challenges

that faced religious leaders. (When Methodist James Woodsworth

arrived in Portage la Prairie in Manitoba in 1882, he was still under

the jurisdiction of Toronto Conference, which at that time stretched from

Belleville to the west coast!)

challenges

that faced religious leaders. (When Methodist James Woodsworth

arrived in Portage la Prairie in Manitoba in 1882, he was still under

the jurisdiction of Toronto Conference, which at that time stretched from

Belleville to the west coast!)

Consolidation was an expression of the impulse to relate to the emerging national culture. Cooperation seemed to be the answer to wasteful competition and depletion of scarce resources — not just money but personnel. (The logic of this principle soon appealed to denominational leaders who proposed an even more ambitious consolidation: union of Protestants across confessional lines to create the United Church of Canada.) But cooperation within and between denominations was not a new idea that dawned on religious leaders only after 1867.

Confederation is often alluded to as the event that sparked organizational convergence, but at the local level cooperation had been going on in various ways prior to 1867. Methodists, for example, had been energized by a series of revivals in the late 1850s, and had worked together for a common cause.

The common sense of mission that accompanied evangelistic endeavors helped

lay the groundwork for the acceptance of the proposed denominational unions,

especially (but not exclusively) among Methodists. Methodists and other

Protestants shared the strong sense of missionary purpose that was sweeping

the Anglo-American world in the late-nineteenth century. Some countries,

including Canada, sent large numbers of missionaries around the world.

But in Canada there was a missionary task even closer at hand: the impulse

to creating a Christian Canada that connected congregations in the Maritimes

with those in the prairies and in-between.

Consolidation solved some problems but created others. Discontents spurred

the growth of new religious denominations that took root in Canada, among

them the Salvation Army, a number of holiness denominations, and the Plymouth

Brethren. And of course, not to be forgotten is the demographic makeup

of the new immigrants who began to arrive in great numbers. Many of them

were Catholic, adding to the complexity of creating a "Christian

Canada": whose brand of Christianity would it be? Such worries were

among the challenges that made even more ambitious plans to consolidate

Protestant influence seem like a good idea at the time.

Anglicans

As of 1875, there were

two ecclesiastical provinces of Anglicans in the dominion of Canada: (1)

the ecclesiastical province of Canada, which included the dioceses in

the civil provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes; and (2) the

ecclesiastical province of Rupert's Land, which included the dioceses

in the North West (today's Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, the Yukon,

and parts of the Northwest Territories). There were also some dioceses

in British Columbia which had not yet joined together as an ecclesiastical

province.

As of 1875, there were

two ecclesiastical provinces of Anglicans in the dominion of Canada: (1)

the ecclesiastical province of Canada, which included the dioceses in

the civil provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes; and (2) the

ecclesiastical province of Rupert's Land, which included the dioceses

in the North West (today's Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, the Yukon,

and parts of the Northwest Territories). There were also some dioceses

in British Columbia which had not yet joined together as an ecclesiastical

province.

(To the left, from the Chilliwack museum, is Caroline McCutheon (1854-1926), a South African in birth who lived in British Columbia from 1859 to 1894. She attended St. Thomas Anglican Church, Chilliwack.)

In 1885 the Canadian

Pacific Railway was completed when Lord Strathcona drove the last spike

at Craigellachie, BC. In the same year an Anglican choir director in Petrolia,

Ontario, proposed a motion at provincial synod for "church consolidation".

The province of Canada invited the province of Rupert's Land to a conference,

which was held in Winnipeg in 1890. They agreed on an organizational plan

which would create a national church, to be called the Church of England

in Canada. It would be governed by a general synod, with jurisdiction

over doctrine, worship, discipline, missions, and certain other matters.

Its chief pastor would be a primate with the title archbishop. There were

many debates about principles and details, but the Winnipeg Scheme with

revisions was accepted in 1893 at the first General Synod in Toronto.

In 1885 the Canadian

Pacific Railway was completed when Lord Strathcona drove the last spike

at Craigellachie, BC. In the same year an Anglican choir director in Petrolia,

Ontario, proposed a motion at provincial synod for "church consolidation".

The province of Canada invited the province of Rupert's Land to a conference,

which was held in Winnipeg in 1890. They agreed on an organizational plan

which would create a national church, to be called the Church of England

in Canada. It would be governed by a general synod, with jurisdiction

over doctrine, worship, discipline, missions, and certain other matters.

Its chief pastor would be a primate with the title archbishop. There were

many debates about principles and details, but the Winnipeg Scheme with

revisions was accepted in 1893 at the first General Synod in Toronto.

Document

2: "Sermon preached at the opening service by the metropolitan of

Rupert's Land," General Synod, 1893

Document

2: "Sermon preached at the opening service by the metropolitan of

Rupert's Land," General Synod, 1893

A "metropolitan" is the head of a province, and is usually styled "Archbishop". (A province is a family of dioceses.) Robert Machray (1831-1904), bishop of the diocese of Rupert's Land (centred on Winnipeg), and also the metropolitan of the province of Rupert's Land (the whole North West, the former Hudson's Bay territory), preached the sermon at the opening service of the first General Synod of the Church of England in Canada. The text is a good source of information for his views of what was to be gained by church consolidation. (Eastern Anglicans would have had rather different views.)

Page 64: The future has "grand possibilities."

Pages 65-65: Machray acknowledges differences of opinion between eastern and western Anglicans about the new church constitution. Most easterners (who would dominate General Synod for the foreseeable future) had wanted to abolish provincial synods; westerners wanted to retain them, and the west got its way.

Page 65: Machray notes that western Anglicans envision three purposes for a General Synod: united practical work; a uniformity of liturgical use; and speaking to Canadian society with one voice. For the rest of the sermon, he will examine the first and the third of these purposes. (Note that he doesn't presume to speak for eastern Anglicans.)

Page 65: Machray notes that Anglicans are following the good example of Presbyterians.

Presbyters: Anglicans, except for Anglo-Catholics, rather seldom used the word "priest" in the nineteenth century, although the word was certainly used in the Prayer Book. "Presbyters" or "ministers" was the more common term.

Pages 66-67: Missions were very important to western Anglicans, since the vast majority of their parish churches were mission churches (i.e., churches that weren't financially self-supporting, and depended on outside aid). They were much less important to Anglicans in the more affluent east, many of whom had resisted church consolidation for fear of being on the hook for subsidizing western missions. Note here that Machray cites the good example of Methodists who have already assumed responsibility for Indian missions (among Anglicans, Indian missions are still being supported from England).

Pages 67-69: In Machray's view, church conslidation for Anglicans should be seen as a step towards a union of all the "estranged and separated brethren". He presumably means English-speaking Protestants, but he doesn't say so. What a grand vision! Where did it come from?

Pages 69-70: Just as Jesus' prayer for unity in the "Farewell discourses," John 17:11, leads to his prayer that his followers may be sancitifed, 17:19, so Machray moves from his vision of a grand inclusive Christian community for Canada to an exhortation towards self-consecration and self-surrenderto God in service.

Lincoln judgment: In 1889 the archbishop of Canterbury, Edward Benson, heard charges brought by evangelicals against the saintly bishop of Lincoln, Edward King, an Anglo-Catholic ritualist who had used advanced forms of ceremonial in public worship, in violation of English law. For instance, he had mixed wine with water in the communion cup. The bishop of Lincoln was cited to appear in an ecclesiastical court headed by the archbishop of Canterbury, E.W. Benson. After a trial, the bishop of Lincoln was exonerated on most charges, and received no sentence on the others. It was the last significant ritual prosecution in England.