Studying Canadian Protestantism

Useful links

Brief history of the United Church of Canada

Brief history of the Anglican Church of Canada

Church history resources for the Anglican Church of Canada from Anglicans Online

A virtual exhibition on William King, a Presbyterian who founded a settlement for fugitive slaves in 1849 (hosted by the Prebyterian Church)

The Dutch Reformed presence in Canada, by a gentleman named Dan Knight

How to understand "religion in Canada" by Roger O'Toole, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, partly descriptive and partly methodological

Transcriptions of a few documents for the history of the United Church of Canada, by the Rev. Don Anderson

Mennonite Historical Society of Canada

Canadian Society of Church History

Review by C.T. McIntire of Terrence Murphy and Roberto Perrin, A Concise History of Christianity in Canada

A guide to Internet resources on worldwide Protestantism, from the Wabash Center

Religion in the U.S. and Canada, also from the Wabash Center

"Religions in Canada," reference document from the Department of National Defence

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada

Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada

Evangelical Fellowship of Canada

Reformed churches in Canada, unofficial site

United Church of Canada Archives Network

Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives

Lutheran Church Archives (Canada, Eastern District)

A large number of links for Canadian religious history, from the Canadian Museum of Civilization

David Bennett, a school teacher in Lunenburg, has this website about Canadian history

Transactions of the Manitoba Historical Society have several articles related to religion

Print bibliography

Anglican Church in the North West, bibliography, from Project Canterbury

Defining terms

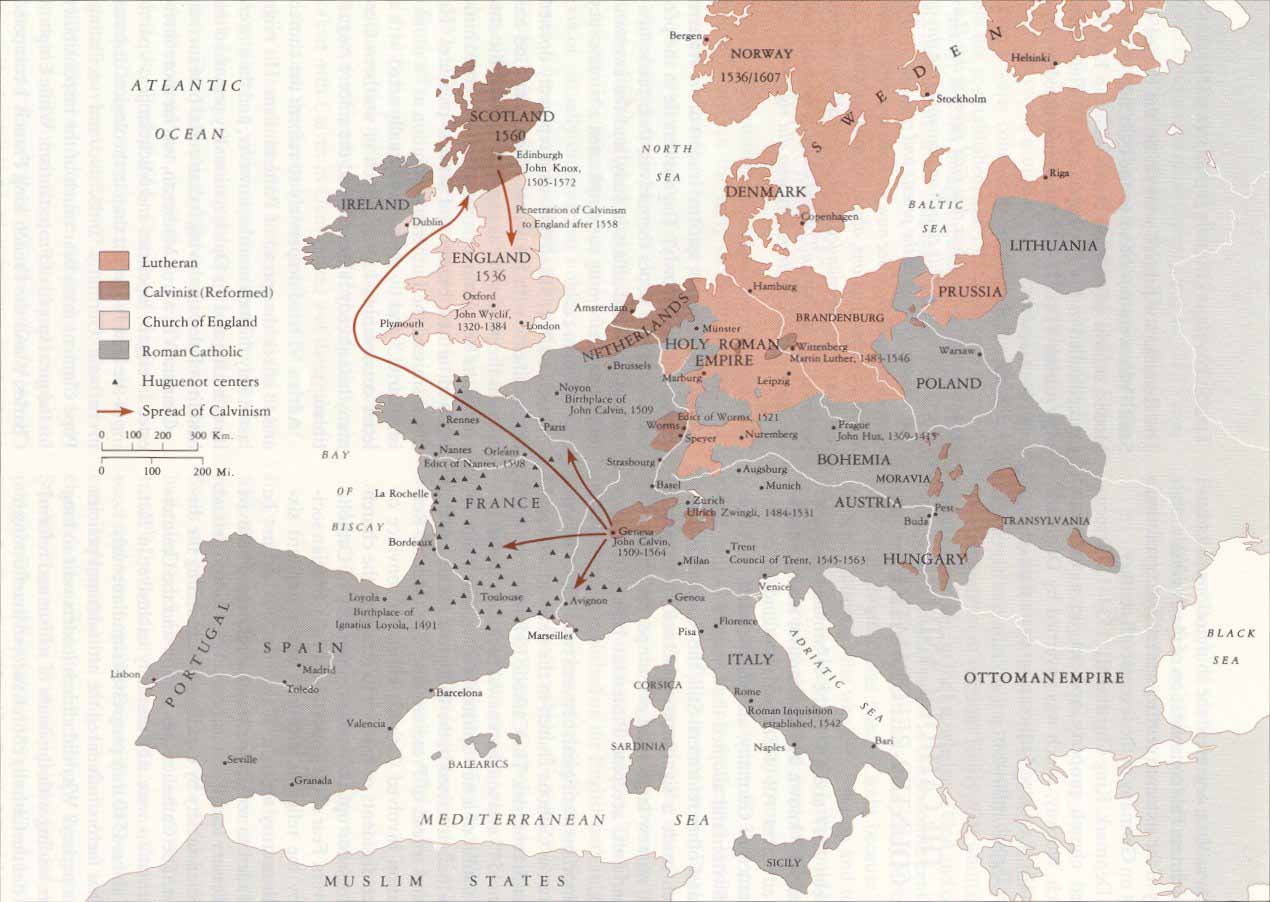

"Protestant" refers to ecclesial groupings which are historical descendants or offshots of those western European churches which during the Reformation of the sixteenth century restructured their organizations and reformed their theology without the permission of the pope (or bishop of Rome). The Protestant churches of the sixteenth century can be divided into two categories:

Churches which

were reformed under the authority of a government. These churches are

sometimes called "mainline Protestant," and include Lutherans,

Reformed, and Anglican. ("Reformed" is used for churches strongly

influenced by the teaching of John Calvin, the chief pastor of Geneva.)

Churches which

were reformed under the authority of a government. These churches are

sometimes called "mainline Protestant," and include Lutherans,

Reformed, and Anglican. ("Reformed" is used for churches strongly

influenced by the teaching of John Calvin, the chief pastor of Geneva.)- Churches which were organized by individual leaders or by groups of believers without the sanction of a government. These are sometimes called "radical Protestant," and are sometimes further categorized into Anabaptist, spiritualist, and rationalist.

Baptists, who baptize only believing adults and not infants, now generally trace their history to the Anabaptists; earlier generations of English-speaking Baptists usually traced their movement to certain Anglicans who beginning in the late 1500s rejected a legal establishment of religion. Methodism began as a revival movement within eighteenth-century Anglicanism.

The term "Protestantism" isn't really an "-ism" in the sense of a theory or set of beliefs, since Protestants disagree among themselves about theology and discipleship.

"Canada" is used in the title of this course to mean any part of North America which now is within the boundaries of Canada. The term was used in a much more restrictive sense between 1791 and 1867 (to mean what is now Ontario and Quebec), and had other meanings before 1763.

The Protestant denominations in Canada

"Christian denomination" is used to mean a reasonably stable organization of congregations and ministries. The underlying sense is that Christianity is a religion practiced under the auspices of a number of alternative associations of believers, and that each of these associations has its own distinctive name or "denomination" and its own distinctive practices and beliefs. In a society which practices religious toleration, as Canada does, the advantage of the neutral term "denomination" is that it allows Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and other Christian groupings the Scriptural name "Christian," without raising the potentially divisive question whether any one of them is more truly Christian than the rest. In other words, the term has a relativizing connotation. Many Christians therefore resist thinking of their own church as a mere "denomination."

The

summary statistics of religious affiliation in Canada, as indicated

by the 2001 census, are linked here. Historically the "big three"

denominations in  Canada

were Roman Catholic, United Church of Canada, and Anglican Church of Canada;

the "little three" were Baptist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian.

But the 2001 census showed, first, that #2 and #3 were much closer in

size to #4, #5, and #6 than to #1:

Canada

were Roman Catholic, United Church of Canada, and Anglican Church of Canada;

the "little three" were Baptist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian.

But the 2001 census showed, first, that #2 and #3 were much closer in

size to #4, #5, and #6 than to #1:

- Roman Catholic: with an affiliation, according to the 2001 census, of 12,793,000 (43.2%)

- United Church of Canada: 2,839,000 (9.6%)

- Anglican Church of Canada: 2,035,000 (6.9%)

- Baptist, 729,000 (2.5%)

- Lutheran, 607,000 (2.0%)

- Presbyterian, 410,000 (1.4%)

Moreover, the 2001 census showed that Christianities other than mainstream Protestant (such as evangelical and non-European) had outstripped the little three: "Christian not included elsewhere" + "Protestant not included elsewhere" represented 4.5% of the population. Finally, the 2001 census showed an unprecedented number of Canadians claiming "no religion" at all: 16.2% of the population.

Needless to say, a great many people who tell census-takers that they are, say, Anglican, are almost never seen in any Anglican church.

Historiography

Historical

writing about Protestantism in Canada can be divided into four periods.

(I've drawn these from John S. Moir, "Canadian Religious

Historiography: An Overview," reprinted in John S. Moir, Christianity

in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Paul Laverdure (Gravelbourg, SK:

Laverdure & Associates, 2002), pp. 136-150.)

Historical

writing about Protestantism in Canada can be divided into four periods.

(I've drawn these from John S. Moir, "Canadian Religious

Historiography: An Overview," reprinted in John S. Moir, Christianity

in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Paul Laverdure (Gravelbourg, SK:

Laverdure & Associates, 2002), pp. 136-150.)

- Before World War I: popular, unscholarly, even propagandistic. Much was published by the very busy presses of the Christian Guardian newspaper, run by the Canadian Methodist Conference, and was geared to showing that Methodism had a very strong, very positive influence on Canadian society.

- From World War I to World War II: writing shifted "from providential history towards a humanistic philosophy," mostly written by secular historians interested in the political origins of Canadian nationality. Moir can find only six or eight religious historical monographs from this entire period.

- From 1945 to the 1960s: religion became one of a great many specialized historical interests among Canadian historians, leading to "historical reductionism and balkanization." Christians continued to do almost all the writing on the history of Christianity, and several triumphalistic denominational histories were written.

- Since the 1960s: social history and social-scientific technique were adopted by historians. A significant number of secular historians now began researching religious themes, and several universities formed departments of religion that were not denominationally affiliated. Academic standards were improved, access to archival resources was opened up, and the number of publications increased. But secular historians tended to assume a theologically liberal viewpoint, and Moir saw signs as he wrote of a tendency to intellectual conformism and political correctness.