Useful links

A helpful and learned overview of fundamentalism from the Religious Movements Homepage Project of the University of Virginia.

Grant Wacker of the Divinity School at Duke University on "the rise of fundamentalism".

A biography of T.T. Shields by a professor at the seminary which he founded.

Print bibliography

Fundamentalism in general, not necessarily Canada

Karen Armstrong, The Battle for God: A History of Fundamentalism. New York: Ballantine Books, 2001.

Brenda E. Brasher, The Encyclopedia of Fundamentalism, New York: Routledge, 2001.

Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby (eds.). The Fundamentalism Project, several volumes, University of Chicago Press.

The acerbic journalist H.L. Mencken writes an obituary of Gresham Machen in the Baltimore Sun, 1937. Mencken had almost as little use for Machen's Calvinism as for cannibalism, but he seems to have liked modernism even less.

Canadian content

Robert Burkinshaw, "Evangelicalism in British Columbia: Conservatism and Adaptability", JCCHS 38 (1996): 77-100

William H. Katerberg, Modernity and the Dilemma of North American Anglican Identities, 1880-1950, Monteal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2001

D.C. Masters, "The Anglican Evangelicals in Toronto 1870-1900", JCCHS 20 (1978) 51-65

David Marshall, " Premier E. C. Manning, Back to the Bible Hour, and Fundamentalism in Canada," in Marguerite Van Die, Religion and Public Life in Canada, 2001, 237-254.

David Priestley, Memory

and Hope, Wilfrid Laurier Press, 1996.

Nina Reid, "Christian Darwinism in the Knox College Monthly, 1883-1896", JCCHS 31 (1989) 15-32

Robert A. Wright, "The glow in the eastern Sky: The impact of Mahatma Gandhi and Toyohiko Kagawa on the Canadian Protestant Churches in the Interwar Years," JCCHS 32 (1990) 3-23

R.C. Chalmers, See the Christ Stand: A Study in Doctrine in the United Church of Canada (1945), chapters 1-4

Alfred Gandier, The Doctrinal Basis of Union and the Historic Creeds (1926)

T.B. Kilpatrick, Our Common Faith, Toronto: Ryerson, 1928

David Marshall, Secularizing the Faith (1992)

J.R.P. Sclater, Modernist Fundamentalism (1926)

N.K. Clifford, "Religion in the Thirties: Some Aspects of the Canadian Experience" in The Dirty Thirties in Prairie Canada, ed. R.D. Francis and H. Ganzevoort (1983)

Donald Schweitzer, "The Great Depression: The Response of North American Theologians," in Gregory Baum, ed. The Twentieth Century: A Theological Overview (1999)

R.B.Y. Scott and Gregory Vlastos, Towards the Christian Revolution (1936)

Harold Wells and Roger C. Hutchinson ed., A Long and Faithful March: "Towards the Christian Revolution," 1930s-1980s (1989), especially Hutchinson's introduction

Michael Bourgeois, "Answering Darwin's Challenge: Evolution and Evangelicalism in the Theology of Richard Roberts," Historical Papers, Canadian Society of Church History (2000)

Michael Gauvreau, The Evangelical century: college

and creed in English Canada from the Great Revival to the Great Depression,

McGill-Queen's University Press, 1991.

John Line, "Barth and Barthianism," Canadian Journal of Religious Thought 6 (1929): 98-104

D.L. Ritchie, "Barth and Barthianism," Canadian Journal of Religious Thought 6 (1929): 317-25

Richard Roberts, The Christian God (1929). (Roberts, a Presbyterian who joined the United Church, became moderator of the United Church of Canada, 1934-1936.)

Richard Roberts, The New Man and the Divine Society: A Study in Christianity (1926)

Modernity

David Lyon of Queen's University, in his study of Postmodernity (1994), gives a helpful description of "modernity" from which the following characteristics emerge:

-

the scientific spirit,

the conviction that the most reliable way to discover truth — perhaps

even the only way — is objective and value-free research into universally

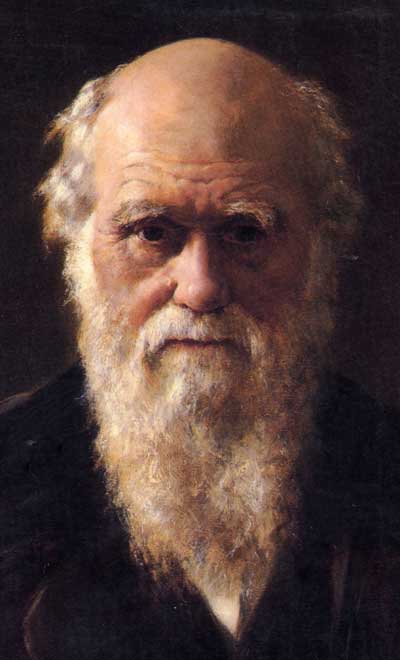

accessible data. In the 1860s this was exemplified perhaps above all

by Charles Darwin, pictured right, whose theory of evolution

flew in the face of Genesis 1-3.

the scientific spirit,

the conviction that the most reliable way to discover truth — perhaps

even the only way — is objective and value-free research into universally

accessible data. In the 1860s this was exemplified perhaps above all

by Charles Darwin, pictured right, whose theory of evolution

flew in the face of Genesis 1-3. - the specialization of life and knowledge, exemplified by people's tendency to compartmentalize their family, work, social, religious, political, economic, and other relationships

- bureaucracy, the rationalized exercise of authority in both the public and private sectors through specialized offices with impersonal procedures

- social interventionism, the view that people can and should make their world a better place through such means as technology, government legislation, and social controls

- what Paul Ricoeur has taught us to call a "hermeneutic of suspicion": a distrust of people's motivations, behavior, beliefs, value systems, religious systems, and historical writings, on the grounds that they are controlled by such unconscious natural forces as class interest (as for Karl Marx), the will to power (as for Friedrich Nietzsche), and sexuality and repression (as for Sigmund Freud).

Modernity

first began appearing on the theological radar screen in Germany. In retrospect,

Friedrich

Schleiermacher (1768-1834), a proponent of the Romantic movement and

a founder and professor of the University of Berlin, has often been seen

as "the father of liberal Protestantism" (pictured left). In

1835 David

Friedrich Strauss' Leben Jesu ("Life of Jesus") treated

the gospels simply as historical documentary sources and interpreted them

in a modernizing way.

Modernity

first began appearing on the theological radar screen in Germany. In retrospect,

Friedrich

Schleiermacher (1768-1834), a proponent of the Romantic movement and

a founder and professor of the University of Berlin, has often been seen

as "the father of liberal Protestantism" (pictured left). In

1835 David

Friedrich Strauss' Leben Jesu ("Life of Jesus") treated

the gospels simply as historical documentary sources and interpreted them

in a modernizing way.

Theology and modernity

From the 1850s, the churches underwent some intense theological struggles with modernity. In particular, should biblical interpretation and doctrine accommodate the discoveries of geology, the theory of evolution, and the sometimes corrosive new methods of historical study? Those who said "yes" were called "modernists". The term "liberal" in theology has much the same meaning. In Anglican circles the term "broad church" was used.

Some prominent theological liberals were appearing in Britain and the United States by the 1850s, and in Canada by the 1870s.

Perhaps the earliest significant scuffle in English-speaking Protestantism began in 1862 when John William Colenso (1814-1883), the Anglican bishop of Natal in what is now South Africa, began publishing advanced criticism of the Pentateuch. He was deposed by his archbishop for heresy in 1863, but the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council overruled the deposition on technical grounds. Canadian bishops, who were profoundly outraged that a bishop was being allowed to teach heresy, called for a meeting of all Anglican bishops worldwide to deal with the crisis. This was the origin of the first Lambeth Conference (1867). The Conference was clearly unhappy with the JCPC's decision and preferred a new bishop of Natal.

Some early Canadian liberals

In 1875 the minister

of the newly built St.

Andrew's Presbyterian Church, King Street, Toronto, D.J.

Macdonnell, raised doubts about the doctrine of eternal punishment

in a sermon on Romans 5:12-21. Some accused him of affirming universal

salvation contrary to the Westminster Confession, and his case made its

way to his Presbytery in 1875 and then to the General Assembly in 1876

and 1877. After a very complicated and divisive ecclesiastical trial,

a way was found to exonerate Macdonnell. It has been argued that this

decision allowed Canadian Presbyterians to take a leading role in higher

criticism and Biblical theology. In 1889 Macdonnell moved a resolution

in Toronto Presbytery for the replacement of the Westminster Confession;

the motoin lost. An

1897 life of Macdonnell is available on line from Our Roots/ Nos

Racines. (Another Presbyterian liberal is John Cambell of Presbyterian

College, Montreal.)

In 1875 the minister

of the newly built St.

Andrew's Presbyterian Church, King Street, Toronto, D.J.

Macdonnell, raised doubts about the doctrine of eternal punishment

in a sermon on Romans 5:12-21. Some accused him of affirming universal

salvation contrary to the Westminster Confession, and his case made its

way to his Presbytery in 1875 and then to the General Assembly in 1876

and 1877. After a very complicated and divisive ecclesiastical trial,

a way was found to exonerate Macdonnell. It has been argued that this

decision allowed Canadian Presbyterians to take a leading role in higher

criticism and Biblical theology. In 1889 Macdonnell moved a resolution

in Toronto Presbytery for the replacement of the Westminster Confession;

the motoin lost. An

1897 life of Macdonnell is available on line from Our Roots/ Nos

Racines. (Another Presbyterian liberal is John Cambell of Presbyterian

College, Montreal.)

In 1890 George Coulson Workman (1848-1936) of Victoria University began arguing that the messianic prophecies in the Old Testament didn't truly foreshadow the historical Jesus Christ. Albert Carman, the general superintendent of the Methodist Church and the chair of the board of regents of Victoria, and Edward Dewart, the conservative editor of the Christian Guardian, led an attack on him. Workman was supported by the president of Victoria, Nathanael Burwash, but the Board decided to remove him from the teaching of theological students, and he resigned and moved to Wesleyan College, Montreal. Another Methodist liberal was George Jackson, also at Victoria, whose vindication in 1910 ended the Methodist heresy hunts. (See George A. Boyle, "Higher Criticism and the Struggle for Academic Freedom in Canadian Methodism," Th.D. thesis, Victoria 1965.)

Frederick Julius Steen (1867-1903), a Wycliffe graduate who taught apologetics and church history at Montreal Diocesan Theological College, aroused suspicion for reading too much Schleiermacher, teaching an untraditional course in apologetics, and being a little loose on Biblical interpretation. He was forced to resign in 1901, and the heartless treatment he received from Archbishop William Bennett Bond probably led to his early death.

Isaac G. Matthews (1871-1959), professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College from 1904 to 1919, began to be criticized in 1908, but kept his job. Ever after, McMaster was suspected by many Baptists as excessively liberal.

It has been rumoured that Charles Venn Pilcher (1879-1961), a teacher at Wycliffe, was quietly eased out 1908 because of his liberal tendencies, but if so, the hard feelings didn't last, for he returned to the staff in 1919.

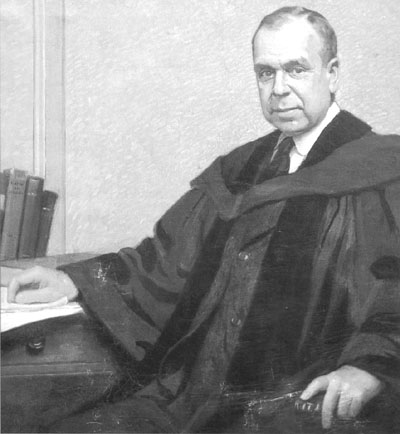

Fundamentalism

The extreme reaction to modernism is commonly called

fundamentalism, and it represents the dissent of many Protestant Christians

to the increasing accommodation of modernism after 1900. In particular,

it sought to protect a theological place for traditional supernaturalism

against modernizing naturalism. Nevertheless, it wasn't simply a restatement

of tradition; it was a new movement in a new age. The intellectual origins

of fundamentalism are complex; it probably draws on American premillennialism,

Scottish common-sense

philosophy, the Princeton school of  Biblical

interpretation associated with John

Gresham Machen (1881-1937), pictured left, and American evangelicalism.

But it wouldn't likely have been so successful if it weren't also a social

and political movement. It spoke for many who felt displaced by the rapid

social changes represented by industrialization, urbanization, and unrestrained

corporate capitalism. See George Marsden, Fundamentalism and American

Culture ...1875-1925 (Oxford University Press, 1980).

Biblical

interpretation associated with John

Gresham Machen (1881-1937), pictured left, and American evangelicalism.

But it wouldn't likely have been so successful if it weren't also a social

and political movement. It spoke for many who felt displaced by the rapid

social changes represented by industrialization, urbanization, and unrestrained

corporate capitalism. See George Marsden, Fundamentalism and American

Culture ...1875-1925 (Oxford University Press, 1980).

The term "fundamentalism" is said to have first been used at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, where an annual Bible conference was held from 1883 to 1897. (Its conservative founders included Cyrus Scofield, the dispensationalist editor of the Scofield Bible, and J. Hudson Taylor, who began the China Inland Mission.) The term is more often connected with the series of theological pamphlets called The Fundamentals, funded by two millionaire brothers in the southern California oil industry, 1910-1915. Among the authors were Dyson Hague, a part-time instructor at Wycliffe College, and William Caven, principal of Knox College.

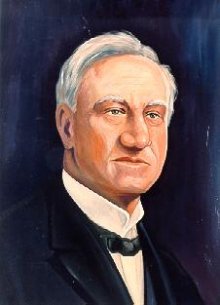

The fundamentalist-modernist controversy split

some U.S. denominations. Most notably, among Presbyterians, Westminster

Theological Seminary was formed in 1921 in protest against the newly liberal

Princeton Theological Seminary, and the Presbyterian Church experienced

schism in 1934. (A

good overview from the perspective of one of the schismatic churches is

linked here.) The controversy in Canada was also bitter but with one

notable  exception

its results were less visibly dramatic. The notable exception was the

schism from the Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec, beginning in

1926, engineered by the indomitable T.T. (Thomas Todhunter) Shields, pictured

right, minister of Jarvis Street Baptist Church, Toronto. (Shields

was unusual among fundamentalists in being an amillennialist.)

exception

its results were less visibly dramatic. The notable exception was the

schism from the Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec, beginning in

1926, engineered by the indomitable T.T. (Thomas Todhunter) Shields, pictured

right, minister of Jarvis Street Baptist Church, Toronto. (Shields

was unusual among fundamentalists in being an amillennialist.)

Notes on Reading 9, i.e., our first reading for this week: Dyson Hague, "The History of the Higher Criticism," from THE FUNDAMENTALS, 1910.

The "higher criticism" was the term for textual criticism. It was typically used for the more modernist forms of Scriptural criticism, such as source criticism, form criticism, and redaction criticism. Hague distinguishes non-modernist (supernaturalist) textual criticism, which he approves, from modernist textual criticism, which he doesn't.

Page 88, the suggestion that fundamentalism is essentially a defence of supernaturalism finds its first support in the last full paragraph. This becomes a theme of the article.

Page 90, the German influence in modernist theological scholarship is recognized here. German influence was also strong on North American graduate education in general. At the first American graduate school, Johns Hopkins University (founded in 1876), virtually all the faculty had received at least some of their training in Germany, and the Berlin model which they adopted there shaped all subsequent North American graduate studies.

Page 97, in his criticisms of the assumptions of the higher critics, Hague is by no means assuming an anti-intellectual perspective, but quite the reverse. He thinks that the higher critics have not carefully scrutinized their own presuppositions. See also page 115, "Not obscurantists." (An obscurantist is not someone who believes in obscurity, but one who prevents the progress of knowledge.)

Page 100, if nothing else, read "the point in a nutshell".

Page 112, a new approach is taken. If Christ is Truth, and if Christ recognized the Pentateuch as Mosaic, he could not be mistaken.