Useful links

(This isn't on war, but it became available recently and we wanted to get your attention. It's a virtual exhibition from the Presbyterian Church on William King, a Presbyterian who founded a settlement for fugitive U.S. slaves in 1849)

Print bibliography

Arthur C. Cochrane, The Church and the War (1940)

Alan Davies and Marilyn F. Nefsky, How Silent Were the Churches? Canadian Protestantism and the Jewish Plight during the Nazi Era (1997)

M.F. McCutcheon et al., The Christian and War: An Appeal (1926)

Tom Socknat, Witness against War: Pacifism in Canada, 1900-1945 (1987)

Charles Thompson Sinclair Faulkner, " 'For Christian Civilization': The Churches and Canada's War Effort, 1939-42," Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago (1975)

Cdn chaplains issue JCCHS vol. 35 Oct 1993

[75 united church ministers,] "A Witness against the War," United Church Observer, October 15, 1931

Gordon L. Heath, "Sin in the Camp: The day of humple supplication in the Church of England in Canada in the Early Months of the south African War", JCCHS 44 (2002) 207-226

Duff Crerar, Padres in No Man's Land (Montreal

and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995

--

J. Michael Bliss, "The Methodist Church and World War I", Canadian

Historical Review, Sept. 1968

David B. Marshall, "Methodism Embattled: A Reconsideration of the Methodist Church and World War I", Canadian Historical Review, March 1985, p. 48-64.

Wars in the 20th century

In Flanders fields the poppies grow ...

Col.

John McCrae, pictured left, the author of this most famous

of Canadian poems, was a Presbyterian from St.

Andrew's Church in Guelph, Ontario, pictured below, right,

where two plaques honour him. He wrote "In Flanders Fields"

in 1915 after the death and simple burial of a close friend. He died in

January 1918 of pneumonia and meningitis. Col. John McCrae was just one

of millions in the 20th century affected by war.

Col.

John McCrae, pictured left, the author of this most famous

of Canadian poems, was a Presbyterian from St.

Andrew's Church in Guelph, Ontario, pictured below, right,

where two plaques honour him. He wrote "In Flanders Fields"

in 1915 after the death and simple burial of a close friend. He died in

January 1918 of pneumonia and meningitis. Col. John McCrae was just one

of millions in the 20th century affected by war.

Yet, it wasn't supposed to be that way ....

The vision at the beginning of the 20th century was of humanity  progressing,

of a time of peace. This is reflected in the minutes and official records

of Protestant denominations in the period prior to 1914. But there were

dark clouds on the horizon. The major powers in Europe — France,

the new nation of Germany, Great Britain, the Austro-Hungarian Empire,

the Ottoman Empire, Italy, and Russia — had become involved in an

arms race. As well, each had made pacts with some of the others.

progressing,

of a time of peace. This is reflected in the minutes and official records

of Protestant denominations in the period prior to 1914. But there were

dark clouds on the horizon. The major powers in Europe — France,

the new nation of Germany, Great Britain, the Austro-Hungarian Empire,

the Ottoman Empire, Italy, and Russia — had become involved in an

arms race. As well, each had made pacts with some of the others.

The world of July 1914 is difficult for us to imagine. The names of some of the countries seem strange. Every one of these European powers, with the exception of France, was ruled by a monarch or an emperor (the Tsar in Russia). All that changed.

World War I

The crisis which sparked the outbreak of World

War I was a minor incident, an assassination

of a minor noble in the Balkans. Yet, this crisis threw all of Europe,

and soon the rest of the world, into a war unlike any seen in history.

Men marched to war confident

of glory, imagining that it would all be over in a matter of weeks and

that they would then be returning to a hero's welcome. The reality was

four years of brutal carnage. Even now, almost ninety years later, the

numbers of casualties in the First World War are numbing. By the time

the war ended four years later, the Central powers (Germany, Austro-Hungary,

Turkey, and other allies) had lost 3.4 million dead, and another 8 million

wounded. The French, British Empire (including Canada), Russia and their

allies had lost an estimated 5 million dead and 9 million wounded.

Men marched to war confident

of glory, imagining that it would all be over in a matter of weeks and

that they would then be returning to a hero's welcome. The reality was

four years of brutal carnage. Even now, almost ninety years later, the

numbers of casualties in the First World War are numbing. By the time

the war ended four years later, the Central powers (Germany, Austro-Hungary,

Turkey, and other allies) had lost 3.4 million dead, and another 8 million

wounded. The French, British Empire (including Canada), Russia and their

allies had lost an estimated 5 million dead and 9 million wounded.

Emperors fell as a result of World War I. The Bolsheviks succeeded in overthrowing the Tsar in Russia, and founding a communist state — although peace on the Western front in 1918 did not affect Russia, where a civil war raged through 1919. The Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires collapsed and new nations, such as Turkey, Austria, and Poland, were created. But the brunt of the blame for the war fell on Germany. The Kaiser abdicated and a Republic was established. Germany was made to pay reparations, or financial payments, to their former enemies . The German economy and new democracy, were no match for the crises which followed the war. The result was the coming to power of a strong-man, the dictator Adolf Hitler. His dream was to build a glorious new kingdom, a third Reich, for the German people which would be purged of all "inferior races", such as Slavs and Jews.

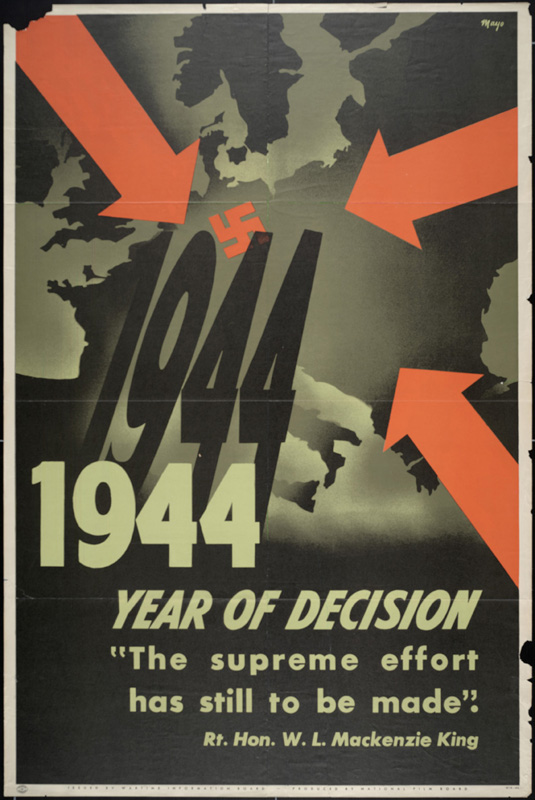

World War II

Where Europe stumbled to war in 1914, every attempt was made to avoid

war in the final years of the 1930's despite the ever increasing ambition

and expansion of the German Reich under Hitler and the Nazis. The invasion

of Poland in 1939 finally forced the France and Great Britain to declare

war against Germany and Italy. World

War II eventually spread around the world, including Japan and the

United States. By the time it was over, the  Axis

powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) had lost 5 million dead while the Allies

(Britain, the United States, Canada and others) had lost over 9 million

dead. Russia alone lost over 7 million dead. At the end of the war, the

world also learned to its horror that the rumours of mass killings of

the Jewish people that seemed beyond belief, had indeed happened. Hitler

and the Nazis had, with great care and malice, planned and attempted to

carry out the extermination of the Jewish people in Europe. The

Holocaust, as the murder of the Jews is known, killed an estimated

6 million Jewish men, women and children. In addition to these 6 million,

Hitler expanded his purification to include other declared "undesirables"

— the mentally handicapped, Slavs, political dissidents, and homosexuals.

An estimated total of 10 million people were systematically murdered by

the Nazi regime. These were not casualties of war. Given that war by this

point had already moved to targeting civilians, the field of battle had

expanded dramatically. The explosion of two atomic bombs, at Hiroshima

and Nagasaki, ushered the world into a new era.

Axis

powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) had lost 5 million dead while the Allies

(Britain, the United States, Canada and others) had lost over 9 million

dead. Russia alone lost over 7 million dead. At the end of the war, the

world also learned to its horror that the rumours of mass killings of

the Jewish people that seemed beyond belief, had indeed happened. Hitler

and the Nazis had, with great care and malice, planned and attempted to

carry out the extermination of the Jewish people in Europe. The

Holocaust, as the murder of the Jews is known, killed an estimated

6 million Jewish men, women and children. In addition to these 6 million,

Hitler expanded his purification to include other declared "undesirables"

— the mentally handicapped, Slavs, political dissidents, and homosexuals.

An estimated total of 10 million people were systematically murdered by

the Nazi regime. These were not casualties of war. Given that war by this

point had already moved to targeting civilians, the field of battle had

expanded dramatically. The explosion of two atomic bombs, at Hiroshima

and Nagasaki, ushered the world into a new era.

The Cold War

The end of World War II brought another major political change. Former allies, the United States and the Soviet Union, emerged as rival superpowers. In the so-called "Cold War" which followed, nuclear weapons were stock-piled and wars were fought throughout the developing world, as each super-power attempted to limit the expansion of the other. Korea. Angola. Indochina/Vietnam. Malaya. Cuba. Nicaragua. Mozambique. Ethiopia. Many of these wars are now forgotten, yet each had a dramatic effect on the countries in which they were waged and on the broader world.

The Korean War

The

Korean war (1950-1953) demonstrates the tensions of the Cold War period.

Korea, which had been occupied by Japan since 1910, was divided into two

regions after World War II. Forces from the Soviet sphere (the region

North of the 38th parallel) invaded the South in 1950. A failure to mention

Korea as a strategic interest in an American government speech may have

led North Korea to assume that this invasion would not be opposed. American

and United Nations forces rushed to defend South Korea. The resulting

war, eventually ended by a truce which established a border very near

the original one, cost the Republic of Korea 591,000 dead and 1.3 million

missing or wounded. North Korean casualty figures (missing and wounded)

stand at close to 1 million. The United States casualty figures stand

at over 33,000 killed while Canadian casualties were 320 killed and over

1,000 missing or wounded.

The

Korean war (1950-1953) demonstrates the tensions of the Cold War period.

Korea, which had been occupied by Japan since 1910, was divided into two

regions after World War II. Forces from the Soviet sphere (the region

North of the 38th parallel) invaded the South in 1950. A failure to mention

Korea as a strategic interest in an American government speech may have

led North Korea to assume that this invasion would not be opposed. American

and United Nations forces rushed to defend South Korea. The resulting

war, eventually ended by a truce which established a border very near

the original one, cost the Republic of Korea 591,000 dead and 1.3 million

missing or wounded. North Korean casualty figures (missing and wounded)

stand at close to 1 million. The United States casualty figures stand

at over 33,000 killed while Canadian casualties were 320 killed and over

1,000 missing or wounded.

The Persian Gulf

The collapse of the Soviet Union and its allies in the Warsaw Pact has

not ushered in peace. Canada went to war

in 1991, in the Persian Gulf in order to stem the expansion of Iraq

into Kuwait.

The churches and war

Each of these wars had, in a different way, a dramatic impact on Canada and on each of the Protestant denominations. Some wars unified the population, at least in English Canada. Others led to division within congregations and the national church, as Christians with differing opinions struggled to know what was faithful. Many members of Christian churches in Canada have first hand experience of war, making the Sunday closest to Remembrance Day a time of remembering and mixed emotions.

Here from Library and Archives Canada is a picture of a church parade (compulsory church service) on board the S.S. Franconia in World War I.

Our class will look at the topic of War and how it has affected Protestant churches, specifically the United Church of Canada (and its antecedent denominations), the Anglican church, and the continuing Presbyterian Church in Canada.

Our readings include several primary sources:

- a sermon preached in 1917

- two articles published in magazines in the early 1940s debating the issue of Pacifism

- an historical article looking at preaching in World War I

A few notes:

- Contrary to how Canadians now like to perceive themselves, Canada was a rather militaristic nation through the late 19th century and much of the 20th century. Our contemporary idea that we are primarily "peacekeepers" has developed only within the last few decades. Canada was a very strong presence, and an aggressive advocate, in the War in South Africa (Boer War), as well as World War I, World War II, and the Korean conflict.

- As vital parts of the Canadian society and establishment, Canadian churches were supporters of the Canadian government in War. Pacifism was a minority position at best. One of the contrasts between the denominations we are studying is that there were a small minority of pacifists in the Methodist tradition (and later the United Church of Canada), but no prominent examples in the Presbyterian or Anglican traditions. As we will see in our class, this changed only gradually over the course of the 20th century until the time of the first Gulf War.

- Pacifism was not a popular position in Canadian society in the 20th century, even if recent comments in the media might lead us to think otherwise. Nor should we assume that there was not popular support for the fight against perceived communist aggression in places such as Vietnam, Angola, or El Salvador.

Questions to consider

What were the various responses of Christians in Protestant denominations to war in the 20th century?

How did these positions change over time? Why might they have changed?

Is there evidence, as Macdonald suggests, of crusader imagery in Eakin's sermon? What are the forces which might lead someone who philosophically opposed war in 1913 to such a position four years later?

"Just war" seems to be the dominant ethical position held by most Protestant churches. How have particular wars and historical events (World War I, World War II, Vietnam, September 11, 2001) affected those positions? Do you see evidence of this in the Niebuhr/Roberts debate?