Phyllis

D. Airhart

Phyllis

D. Airhart Phyllis

D. Airhart

Phyllis

D. Airhart

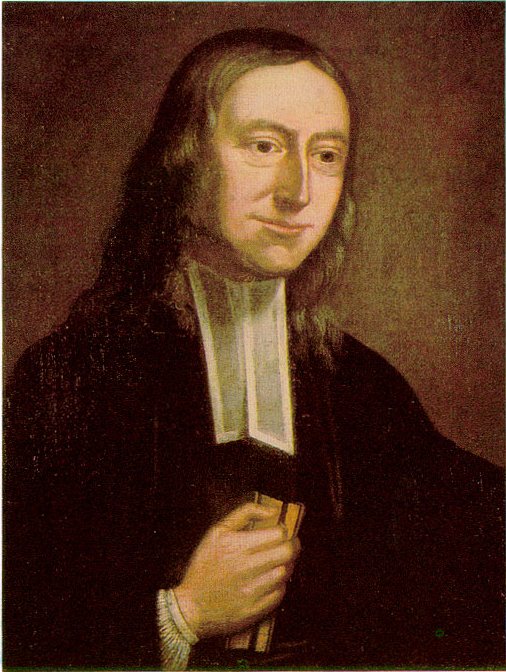

Memory and Mission: John Wesley at 300

Emmanuel College

October 25, 2003

A conversation with my husband Matthew a few nights ago revealed just how little church history I've managed to teach him over the course of nearly 25 years of marriage. I mentioned that I would not be having dinner with him on Saturday because I would be at our Wesley conference progressive dinner that evening. The shocking truth became apparent with Matthew's response to my description of the route of our progressive dinner: we would begin at Victoria, walk over to Wycliffe, and end up at Trinity. "Wycliffe and Trinity? he exclaimed. "Why are you going there? Didn't the Anglicans turf Wesley out of their church?"

Well not exactly. Wesley himself

remained a member of the Church of England all his life, whatever some of his

co-religionists may have thought of his ministry, and our planning committee

wanted to highlight that continuing connection. And yet Matthew is not alone

in thinking of Wesley as something "other" than Anglican. Just how

far does the Wesleyan heritage extend? Imagine for a minute: if Wesley were

with us in any more than spirit for our celebration of his birth 300 years ago,

where would we expect him to worship tomorrow morning? Where might we expect

reports of a "Wesley sighting"?

Well not exactly. Wesley himself

remained a member of the Church of England all his life, whatever some of his

co-religionists may have thought of his ministry, and our planning committee

wanted to highlight that continuing connection. And yet Matthew is not alone

in thinking of Wesley as something "other" than Anglican. Just how

far does the Wesleyan heritage extend? Imagine for a minute: if Wesley were

with us in any more than spirit for our celebration of his birth 300 years ago,

where would we expect him to worship tomorrow morning? Where might we expect

reports of a "Wesley sighting"?

My guess is that he would want to hear Richard Heitzenrater preach at Metropolitan United, once dubbed the "cathedral of Methodism." Perhaps he would instinctively worship with the nearest Anglican parish at Church of the Redeemer. Yet some would argue that there is little memory of Wesley in either the United or the Anglican churches in Canada today. They would bet on spotting him at a Free Methodist church, or one of the other denominations that grew out of Wesley's emphasis on holiness-perhaps with the Church of the Nazarene or the Wesleyan Methodists. Others might look for him among those who minister to the marginalized-the Salvation Army perhaps, or with those like the Pentecostals whose experience of religion is more visibly manifest. Or perhaps the Wesleyan heritage in Canada has been so lost that it is only Methodism as it is brought to Canada from places like Ghana that represents the real Wesleyan heritage. Wesley's influence seems to be ubiquitous and yet, in the minds of some, the Wesleyan heritage is nowhere to be found.

Over the years, and again this weekend, Richard Heitzenrater has convincingly

demonstrated the difficulties inherent in finding the real Mr. Wesley. It should

come as no surprise that Wesley's lingering legacy in Canada has been likewise

elusive. Those laying claim to the Wesleyan heritage in Canada have been looking

for the "real" Wesley almost from the beginning. I want to give a

few examples of how Wesley was remembered in different ways by Canadian Methodists

to illustrate the complexity at the heart of the theme of this conference: the

relationship of memory and mission, in anticipation of the discussion of fidelity

and change that will follow.

We sometimes assume that our memory of the past drives our mission in the present-or

at least ought to give direction to it. I think this is only partly true, at

least for the Wesleyan heritage as it developed in Canada. Memory does indeed

shape mission; but the way we understand our mission sometimes shapes what and

how we think of the past, how we selectively forget certain parts of the past

and distort others-or whether we think of the past at all. Memory has shaped

mission; but mission shapes memory. And like individual memory, collective memory

can fail. I will suggest that our present situation in Canada today presents

some particular challenges for attempts to connect memory and mission.

When John Wesley died in 1791, there were few Methodists in all of British North America to mourn his passing or remember his life. In what is now the six provinces of Canada from Newfoundland across to Ontario, Wesley's movement was made up of about half dozen preachers and less than a thousand members. Those numbers changed dramatically in the century following Wesley's death. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Methodist church had become the largest Protestant denomination in Canada.

Those who scoffed at Wesley and his group in England had ridiculed the regularity with which he and his group methodically carried out religious practices such as prayer, study, fasting, partaking of Holy Communion and acts of charity. But it was other "methods" that came to characterize Methodism when it arrived in our country: the methods of revivalism. Methodists did not "invent" revivalism; but they quickly recognized it as a very effective way of dealing with communities that had no well-organized pastoral charges and were predominantly rural and frontier. In the stories that the first Canadian Methodists told about Wesley, he was transformed from High Church Oxford Anglican to one of the greatest revivalists the Christian church had ever seen. The Wesley they remembered bore a close resemblance to their own Canadian Methodist ministers: he too was saddlebag preacher who had gave up the comforts of a home with Molly to preach the message of Methodism. A circuit often encompassed a very large area, and the long distances made it impossible for a minister to visit a point more than a few times a year. It is not surprising that sermons ending with a call for conversion were commonplace: if you feared for the spiritual welfare of those you were preaching to, and might not see them for a few weeks or even months, the priority was on securing their eternal well-being.

During the nineteenth century, Wesley and the Wesleyan heritage were reinvented to support the changing mission of Methodism as its size and influence grew. Sometimes a few details of Wesley's life were forgotten in the process. For example, support for the temperance movement is so closely identified with the Wesleyan heritage that Wesley now tends to be "remembered" as teetotaler. But while Wesley disapproved of the use of "ardent spirits" like whiskey and gin, and heartily recommended water as his beverage of choice, there is evidence to suggest that he drank and even enjoyed wine, though perhaps not as much as did John Calvin who received rather large quantities of wine to cover part of his salary!

Temperance is only one of the issues where Methodism became caught up in a vision of the church that had as its mission the cultivation of both personal righteousness and social righteousness. For nineteenth-century Methodists, conversion was a life-changing experience. Methodists are sometimes remembered for their emphasis on what they were not allowed to do after this experience: no drinking, no dancing, no card playing, no theatre attendance (and later no moving pictures), no smoking. But before we too hastily dismiss what from our perspective looks like a rather joyless and moralistic religion, it is good to keep in mind what they thought was at stake when they insisted on this strict code of behavior. An experience of salvation had implications for how one lived and thus had both personal and public dimensions.

Methodism's social concern, of which the temperance movement is a notable example, opened up a whole world of issues that were at the cutting edge of progressive social reform. Methodists learned to recognize the social aspects of sin, a lesson which later made them appreciate the social gospel message. They recognized very early on the organic nature of social relationships-the interweaving of home, community and nation-as they observed the consequences of alcohol abuse which was widespread. This helped to create an environment in the Methodist church that was very hospitable to the social gospel. Not surprisingly, in the twentieth century Methodists were found at the forefront of the Canadian social gospel movement. The Methodist Church, as well as smaller holiness denominations who looked to Wesley as their theological guide, now recovered the memory of him as both evangelist and social reformer. The mission of "Christianizing the Canadian social order" became part of the founding vision of the United Church as well.

Like Wesley's

medallion here in the Victoria College chapel, which changes in appearance depending

on how the light is shining through it, many Methodists of the progressive era

believed that their age had more light to cast on Wesley's image. They believed

that in emphasizing social responsibility they had found an element of Wesley's

work that had not been adequately appreciated to that point. As the Methodist

church prepared for church union, its understanding of its tradition was under

reconstruction, and with it the memory of the Wesleyan heritage. These Methodists

still recalled the memory of Wesley's experience at Aldersgate, where he felt

his heart strangely warmed; they remembered Wesley the itinerant evangelist.

In their efforts to revitalize Christianity in Canada by offering an new approach

to piety, for which a passion for a social reform was a key element, the spiritual

leaders of Canadian Methodism in the early twentieth century were convinced

that they too were preserving the spirit, if not the letter, of Methodism no

less than those who looked to the past to defend more familiar ways.

Like Wesley's

medallion here in the Victoria College chapel, which changes in appearance depending

on how the light is shining through it, many Methodists of the progressive era

believed that their age had more light to cast on Wesley's image. They believed

that in emphasizing social responsibility they had found an element of Wesley's

work that had not been adequately appreciated to that point. As the Methodist

church prepared for church union, its understanding of its tradition was under

reconstruction, and with it the memory of the Wesleyan heritage. These Methodists

still recalled the memory of Wesley's experience at Aldersgate, where he felt

his heart strangely warmed; they remembered Wesley the itinerant evangelist.

In their efforts to revitalize Christianity in Canada by offering an new approach

to piety, for which a passion for a social reform was a key element, the spiritual

leaders of Canadian Methodism in the early twentieth century were convinced

that they too were preserving the spirit, if not the letter, of Methodism no

less than those who looked to the past to defend more familiar ways.

Not everyone agreed with their assessment then or now. Glenn Lucas has argued that "a genuine 'Wesley' tradition had largely disappeared from Canadian Methodism before 1925 and was entirely abolished with church union." There is now no major Methodist denomination in Canada, and he sees only limited traces of Wesley's evangelicalism with its deep roots in catholic tradition. (James Udy and Eric Clancy, eds., Dig or Die, 140-1) What happened to the Wesleyan heritage? With the creation of the United Canada, of course, the Methodist name has become a far less visible feature of the spiritual marketplace. Statistically, those whose name includes either the word "Methodist" or "Wesleyan" number under 160,000. Even if you stretch "Wesleyan" to add holiness and pentecostal groups it's hard to come up with more than a million or a million and a half. Theologically, the emphasis of the church union movement in Canada, and of the twentieth century ecumenical movement more generally, has been on what traditions held in common. This accelerated the process of forgetting the distinctive features of the past. There was no longer a need to refer to the Wesleyan tradition in particular as part of an appeal to tradition (or Calvin or the Westminster Confession for that matter) to support the mission of the church.

And yet I would like to suggest that Wesley's elusive presence, if not his name, has lingered in the United Church in more ways than we generally acknowledge. Some of the features of the movement he launched are still very much present even in aspects of United Church life that frustrate those both inside and out. Admittedly many distinctive practices of early Methodism are long gone, just as some who feared for their preservation predicted. Gone are class meetings; in their place are special purpose groups that are more likely to inspect issues than the religious experience of those gathered. Gone are love feasts; but still present is a spirit of hospitality still much in evidence in church suppers and other events where food is shared.

I think in fact that one can identity many parallels between the ethos and concerns of Wesley's movement and various expressions of Methodism in Canada-in the United Church of Canada and I expect in other denominations as well. Here are a few examples in no particular order to illustrate: Music continues to be central. There is a Methodist lineage from Wesley to Voices United that suggests that it is in our hymns that we sing our faith. Wesley's critics accused him of producing thin theology; our theology has been likewise characterized as rather meager. Wesley did not evade controversy and in some cases his actions sparked it; his spiritual descendants, at least in the United Church, have not shied away from taking positions and engaging in practices that spark strong reaction. Both John and his brother Charles had concerns about the quality of ministerial candidates that were drawn to Methodism; I suspect there are some who feel the same way now. Wesley found himself dealing with ineffective and rigid church structures and wanted to restructure them; some would see parallels on that score as well. He dared to propose a revision of the 39 articles on which the Church of England had relied for generations; that too has a familiar ring. There was confusion in his day and ours about who could and could not administer the sacraments. Both Wesley and the United Church have attracted radicals despite their own instincts to be moderate or even conservative. Like Wesley we have a longing for improvement, if not perfection, although nowadays we are more likely to express such aspirations in terms of political rather than personal morality. And some United Church leaders might be gratified to discover that Wesley was not always as assured and certain of his faith as we might expect a prominent spokesperson to be. Like Wesley the United Church seems rather attracted to Anglicanism, and we have flirted (though to this point resisted) reuniting.

As I reviewed some studies of Wesley to gear up for this presentation and started jotting down some of these family resemblances to Wesley and his movement, a impertinent thought crossed my mind: is the problem that there is too little of the Wesleyan heritage in the United Church-or too much? But of course the parallels are there because Wesley was first and foremost the founder of a Christian movement. Wesley's mission was not to start a movement for the sake of novelty, but to reclaim and proclaim the Christian message. Thus it may be as difficult to try to identify which aspects of our faith practices are really Wesleyan as it is to claim we know which of the pictures of Wesley we saw last night bear the closest resemblance to the real Wesley.

Wesley is a fascinating and even admirable leader despite, and in some ways even because, of his flaws and human frailties. He is rightly given an important place in the history of Christianity as one who succeeded raising up the people called Methodists as a movement within the Church of England that quickly grew beyond it. He had a grand design to combine the evangelical with the catholic, and to combine individual transformation with a socially responsible way of life. But over time, his spiritual descendents in Canada have found it difficult to hold those elements in tension.

While a century ago failure to live up to Wesley's ideals was lamented in Methodist circles, we rarely hear such regrets expressed today, except perhaps among those of us who are members of the Canadian Methodist Historical Society. The memory of Wesley has seemed to fade, though we bring him out and dust him off from time to time on occasions such as this weekend's celebration. Why has the Wesleyan heritage seemed elusive to the point of near disappearance in twentieth-century Canada? It is not for lack of historical research. Indeed Methodism has been the subject of some of the finest studies of religion in Canada in recent years. But simply having access to more information about the Wesleyan heritage has not, I suspect, done as much as some might have hoped to connect mission and memory.

The story of Methodism as it relates to Canada no longer seems to function as a collective religious memory, one that those claiming the Wesleyan heritage turn to instinctively to create a framework for experience, formation, or action. We do not lack information about the Wesleyan heritage; what we lack is a sense of how that story connects with our religious identity today. This I think is a matter of concern-not just because memory of Wesley is disappearing, The more pressing issue concerns access to Christian memory of which it is a part. If the future well being of religion and the church's mission depend on memory of our past, indications are, that future is precarious.

This is the conclusion

of one of the most interesting studies of the transmission of religious tradition

that I have come across in recent years. In her book titled Religion as a

Chain of Memory, French sociologist Danièle Hervieu-Léger

dissects the problem of connecting memory and mission. Her work deals with a

problem she sees in France, one that I think we recognize in Canada: we live

in a culture where religion has become deprived of a collective memory of a

religious past that is consciously passed on to others. As a culture, we no

longer value memory, and we have become less adept at imagining a chain of belief

that connects who we are to the past. Hervieu-Léger describes a process

of constructing collective memory that is very similar to how we saw Canadian

Methodists reclaiming Wesley in different ways. Constructing collective memory

is, as she puts it, a process of "selective forgetting, sifting and retrospectively

inventing" that is part of a group's self-definition. (124-25) Individual

memory is then regulated by this collective memory. (It is interesting to think

about Methodism and church union in Canada in this light. At the time some Methodists

were dismayed by what they saw as the selective forgetting of significant parts

of the Wesleyan past in efforts to tell the story of the past in a way that

emphasized what the uniting traditions had in common.)

This is the conclusion

of one of the most interesting studies of the transmission of religious tradition

that I have come across in recent years. In her book titled Religion as a

Chain of Memory, French sociologist Danièle Hervieu-Léger

dissects the problem of connecting memory and mission. Her work deals with a

problem she sees in France, one that I think we recognize in Canada: we live

in a culture where religion has become deprived of a collective memory of a

religious past that is consciously passed on to others. As a culture, we no

longer value memory, and we have become less adept at imagining a chain of belief

that connects who we are to the past. Hervieu-Léger describes a process

of constructing collective memory that is very similar to how we saw Canadian

Methodists reclaiming Wesley in different ways. Constructing collective memory

is, as she puts it, a process of "selective forgetting, sifting and retrospectively

inventing" that is part of a group's self-definition. (124-25) Individual

memory is then regulated by this collective memory. (It is interesting to think

about Methodism and church union in Canada in this light. At the time some Methodists

were dismayed by what they saw as the selective forgetting of significant parts

of the Wesleyan past in efforts to tell the story of the past in a way that

emphasized what the uniting traditions had in common.)

Hervieu-Léger argues that we are now witnessing "the collapse of the framework of collective memory which provided every individual with the possibility of a link between what comes before and his or her actual experience." (130) She and others detect something different from the typical reconstruction of collective memory that has characterized the transformation of religion in the past. Indeed, some warn that it is indicative of "a definitive disintegration of religion." (139) One of the consequences of this loss of collective memory is an accelerated shift towards individualized spirituality (140) evident in the emphasis on self-help and self-realization that we find in much of what goes by the name of "spirituality" today.

The interest in spirituality signals a pervasive spiritual hunger that presents the church with opportunities. And yet it is not without its hazards. Martin Marty was recently reported in the Presbyterian Record's account of his lecture in Montreal as warning those gathered about pop spirituality, and is quoted as saying: "The biggest threat within the Christian world is the rise of individualized spirituality"-those who see themselves as "spiritual but not religious." (April, 2003)

Hervieu-Léger would likely concur, and she sees consequences beyond religion: without a memory of cultural continuity it is hard to imagine a common future. We are not only post-modern; we are now witnessing, to borrow a phrase from her, the emergence of a "post-traditional" generation, for whom the world of tradition has collapsed, replaced by a world where signs and language lack historical depth. (164-65) This does not mean that tradition is useless in creating a system of meaning; it does mean that the authority of tradition is limited by the willingness of individuals to submit to it. Its power can no longer be assumed by its representatives nor imposed by them. (167) When there is a conflict between individual experience and conformity to an institutional interpretation of tradition, experience has primacy. (170)

She sees the critical task of religious institutions, the task on which their survival may depend, as coming to terms with the problem of the broken chain of memory. (168) How will organized religion deal with the problem of "propagating and reprocessing" religious signs, now that picking and choosing among them is an individual matter? The last paragraph of her book invites investigation into an area which she says is "ambitious, probably too ambitious" involving the problem of transmission of tradition-that chain of memory-in modern societies. She wonders, how do you reconstruct the "continuing line of belief" when the common experience of individual believers today provides no support for such an endeavor? (176) To bring it back to where we are: how do we reconnect memory and mission?

Answering that question is the task of the next panel, but I will raise a few questions with quick observations in closing. Where do we find the "real" Wesley who will provide inspiration for our mission-perhaps even like Marcus Borg's Jesus, the Wesley we've never known? Or, we might well ask, does remembering the Wesleyan heritage still matter given the rather gloomy outlook for religious tradition in general? And at first glance Mr. Wesley seems to have left us a legacy that is far too elusive and ambiguous to be helpful. Whatever Wesley may have intended, Wesleyanism as it has developed can be viewed as an earlier stage of the subjectivization of religious experience that has helped to break the chain of memory. Wesley and Wesleyanism valued the authority of religious experience and sought assurance in experience as a signal of transcendence. He was fascinated by the accounts of religious experiences of his Methodists and wanted to hear about them-from both men and women as we learned from Molly. He collected and published testimonies of such accounts. And he tried, not always successfully, to reconnect those experiences to the broader Christian memory within and beyond the Church of England.

Perhaps that effort to reconnect is the nexus: why Wesley still has something

to offer the search for a model for ministry with the post-traditional generation,

those whose primary authority in religious matters is their own subjective experience.

Is there something to be learned from the Wesleyan model about how to channel

religious energy in a way that will restore spiritual vitality and begin to

repair the broken chain of Christian memory?

There is a certain irony in the position of many denominations organized by

Wesley's spiritual descendants. Many of them are in a position oddly similar

to the Church of England of Wesley's time as it struggled to satisfy the religious

longings of the day. In the recent census figures to which I alluded to earlier,

I noted the small numbers of those whose religious affiliation might be considered

in some sense "Wesleyan" or "Methodist". The decline in

many of these denominations in the past decade stands in striking contrast to

another census category: those who chose to identify themselves as having "no

religion". This group is numbered at nearly 4.8 million, even excluding

those who self-identified as agnostic, atheist, or humanist. Compare this to

the United Church at a little over 2.8 million and the Anglican Church at a

little over 2 million.

I suspect that the group identifying themselves as having "no religion" includes many who also describe themselves as "spiritual but not religious". Many in Canada today no longer expect to find their spiritual needs met by institutional religion, and find no reason to belong to them. Wesley saw many in his day who felt the same way about institutional religion. He was committed to creating communities that would bring together the various individual expressions of spiritual longing. His movement in England and in North America sought to channel the intuitive, personal dimensions of popular religion with its emphasis on personal authority into a disciplined framework.

Perhaps we also need to recover the part of the Wesleyan heritage that challenges, as Wesley did, the complacency of organized religion-even the valuing of toleration and inclusion that can tend toward a too easy acceptance of things as they are. Emulating Wesley's "catholic spirit" does not mean standing for nothing or doing nothing. But I think that Wesley not only had a catholic spirit; he had a catholic memory which provided him with a toolkit of spiritual practices. In his efforts to renew the 18th century church, we see him introducing seemingly "new" practices which turn out to a retrieval of very old practices borrowed from the early and medieval church, and his own Anglican tradition.

Finding a way to minister "outside the box" of the parish system

was Wesley's mission in the 18th century; it may still be ours in the 21st century.

Wesley expected far more than a "warmed heart". Methodists participated

in organized communities of mutual support. They were directed to avenues of

service to God and neighbour. And let's not forget that they were expected to

learn about the Christian faith, not only through reading the Bible and other

books, but by singing. As we look for ways to rebuild Christian memory this

is an aspect of the Wesleyan heritage that we should continue to proudly lift

up as in the past. Perhaps it is not surprising that both Wesley's movement

and others at this conference have recognized the importance of worship and

especially music.  The

poet Kathleen Norris recounts in her book Dakota: A Spiritual Geography

the story of her return to church after being away for many years. It was at

first the hymns that she had loved to sing as a child that drew her back to

church. She writes, "I am just now beginning to recognize the truth of

my original vision: we go to church in order to sing, and theology is secondary."

(91) This is perhaps only partly true: the singing and the theology may be one

and the same.

The

poet Kathleen Norris recounts in her book Dakota: A Spiritual Geography

the story of her return to church after being away for many years. It was at

first the hymns that she had loved to sing as a child that drew her back to

church. She writes, "I am just now beginning to recognize the truth of

my original vision: we go to church in order to sing, and theology is secondary."

(91) This is perhaps only partly true: the singing and the theology may be one

and the same.

This is all the more important as we think of the repairing the broken chain of religious memory. For Wesleyans at least, and maybe more than most, singing is important. We sing our faith; we remember those "old" hymns; like Kathleen Norris, one of the reasons we come together is to sing. Hymns may be a way to help to teach the faith, and thus a way to restore the broken chain of Christian memory.

And finally, perhaps we need to remember the Wesley who refused to use fidelity

to the past as an excuse to avoid or escape change. Wesley did not become frozen

in the past structures or practices of his church or even his own personal past-nor

should we be frozen in either our past or our present age as we continue to

honour the Wesleyan heritage. Perhaps there is yet more light that will shine

through Wesley's writings. Perhaps best of all is that we may yet come to share

Wesley's confidence that God is still with us as we move ahead.