Background: The Liturgical Movement in the Roman Catholic Church

- Research and reflection into liturgical origins were stimulated by the Benedictine revival of the 1830s — Dom Guéranger (1805–1875), the priory of Solesmes, L’année liturgique (1841–1866), Institutions liturgiques (1840–1851)

Pius X

(pictured right): his "motu proprio" of 22 November 1903 called

for the active participation of the laity in worship; in 1905, he issued

a decree on frequent communion

Pius X

(pictured right): his "motu proprio" of 22 November 1903 called

for the active participation of the laity in worship; in 1905, he issued

a decree on frequent communion - The re-discovery and attribution of the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, 1906–1910, gave liturgists a purported model of the ante-Nicene liturgy. This was very influential.

- One of the most important and characteristic leaders of the early Liturgical Movement was Dom Lambert Beauduin (1873–1960) of Mont César. He critiqued individualistic piety at Malines in 1909. He gave a theology of the body of Christ. He was influential in publishing la vie liturgique, the ‘Semaines liturgiques’

- Less characteristic but also influential was Odo Casel (1886–1948) of the Benedictine monastery at Maria Laach, author ofThe mystery of Christian worship.

- Other Benedictine connections: Klosterneuberg; St. John’s, Collegeville, Minnesota (which publishes the journal Worship)

- Within the Roman Catholic Church the Liturgical Movement was slow to gather supporters, and was hindered by rivalries and disagreements. Attempts were made to silence Beauduin

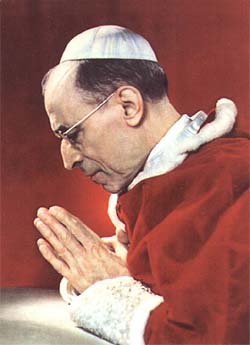

Pope

Pius XII (1876–1958; pope from 1939; pictured right) represents

a turning-point, since he both supported and set limits on the Liturgical

Movement. His encyclical Mystici corporis (1943) legitimized

Liturgical Movement thinking of the Church as the mystical body of Christ.

His encyclical Mediator dei (1947) generally affirmed the Liturgical

Movement, but included strictures on subjectivity and lex orandi

lex credendi

Pope

Pius XII (1876–1958; pope from 1939; pictured right) represents

a turning-point, since he both supported and set limits on the Liturgical

Movement. His encyclical Mystici corporis (1943) legitimized

Liturgical Movement thinking of the Church as the mystical body of Christ.

His encyclical Mediator dei (1947) generally affirmed the Liturgical

Movement, but included strictures on subjectivity and lex orandi

lex credendi - In the following decade leading up to Vatican II, the cause of liturgical form in the Roman Catholic Church was supported by liturgical conferences and certain reforms in policy

- Vatican II represents the triumph of the Liturgical Movement. Things to know: aggiornamento; the publication of Hans Küng et al., The Council and Reunion (1963); the constitution Sacrosanctum concilium (1963); Consilium (1964); new rites (missal 1970)

For further reading see John Fenwick and Bryan Spinks, Worship in

Transition (NY: Continuum, 1995)

The parish communion movement in the Anglican

church

- The classical shape of Sunday morning Anglican worship from the sixteenth century to the 1890s was Morning Prayer — Litany — Antecommunion, with Communion once a quarter. From then to the 1970s there were various models, but a typical one was Morning Prayer three Sundays a month, Communion once a month.

Many voices were raised

in the 1920s in favour of weekly communion. These include Charles Gore

(1853–1932), pictured right, author of The body of Christ: an

enquiry into the institution and doctrine of Holy Communion (1901);

Henry de Candole (1895–1971) at St. John’s, Newcastle (1926–1931).

Many voices were raised

in the 1920s in favour of weekly communion. These include Charles Gore

(1853–1932), pictured right, author of The body of Christ: an

enquiry into the institution and doctrine of Holy Communion (1901);

Henry de Candole (1895–1971) at St. John’s, Newcastle (1926–1931).

- In the 1930s the parish communion movement took shape. Very influential in this was A.G. Hebert (1886–1963), who visited Mont César and Maria Laach in 1932, and published Liturgy and Society (1935). Themes of the book include: his protest against individualism; his understanding of liturgical formation; a theology of liturgical mystery; a theology of the whole people of God; a theology of offering in liturgy. His book Parish Communion followed (1936)

- Several Anglican organizations emerged to champion parish communion, most notably Parish and People (C of E), with origins in 1948; and Associated Parishes (U.S.A.), with origins in 1946

- Most Anglican parishes in the English-speaking world moved to weekly communion in the period 1960s–1980s.

- The appeal of weekly communion:

It helped overcome wars of churchmanship

It sought to unites people liturgically

It clarified the office of the clergy and the ministry of the laity

It offered a highly integrated theology of Church, liturgy, and ministry - Criticisms of weekly communion (here concentrating on criticisms made

by Michael Ramsey, then bishop of Durham, in Durham Essays):

It made communion a little too comfortable; the discipline of conscientious self-examination came to be lost

The daily offices were seldom used afterwards

Ramsey detected a Pelagian tinge in the enterprise

For further reading see Alan L. Hayes and John Webster, What Happened to Morning Prayer? (1997)

The Anglican Liturgical Movement

- The influence of the Roman Catholic Liturgical Movement on leading Anglican thinkers, such as W.H. Frere, can be seen in the 1920s and 1930s. (The Liturgical Movement also influenced other communions as well.)

- Exerting a huge influence in the Anglican world and beyond was Dom Gregory Dix (1901–1952), and his almost inexplicably successful book Shape of the Liturgy (1945). He took Hippolytus as the model of early Christian worship, and emphasized the importance of tradition.

- Massey Shepherd (1913–1990), who wrote a large amount on Anglican liturgy and was a principal speaker at the Anglican Congress of 1954, Minneapolis, was also influential.

- Lambeth 1958 supported liturgical reform.

- At the Keele Conference of 1967, the first conference of Anglican evangelicals, the final document gave a greater-than-expected support to the direction of the Liturgical Movement

- Revisions of the Book of Common Prayer, or alternative liturgies, dominated the worldwide Anglican agenda 1964–1985

For further reading see Alan L. Hayes, “Tradition in the Anglican Liturgical Movement 1945–1989”, in Anglican and Episcopal History 69 (2000) 22–43

The Canadian scene

- The 1959 revision of the BCP, confirmed in 1962, was the last of the traditionalist revisions

- In 1965 General Synod called for a new BCP in modern English. Diocesan bishops were permitted to authorize exploratory liturgical uses. There followed the era of “the paperback liturgies”

- In 1971 General Synod mandated creating alternative services. See BAS, Introduction, pp. 7ff.

Creating the

BAS was given to the Doctrine and Worship Committee of General Synod

1971–1985. Paul Gibson as liturgical officer staffed the Committee.

Significant contributors included Eugene Fairweather (Trinity), pictured

right; David Holeton (Trinity / Vancouver School of Theology), William

Crockett (Vancouver School of Theology), Joachim Fricker (dean of Niagara,

later bishop of the Credit Valley), and, for music, George Black (Huron

College). The BAS was produced in 1985 (distributed 1986).

Creating the

BAS was given to the Doctrine and Worship Committee of General Synod

1971–1985. Paul Gibson as liturgical officer staffed the Committee.

Significant contributors included Eugene Fairweather (Trinity), pictured

right; David Holeton (Trinity / Vancouver School of Theology), William

Crockett (Vancouver School of Theology), Joachim Fricker (dean of Niagara,

later bishop of the Credit Valley), and, for music, George Black (Huron

College). The BAS was produced in 1985 (distributed 1986). - The BAS was initially controversial and the response mixed, often because of pastoral ineptitude in its introduction into various parishes and dioceses.

- Prayer Book Societies were formed or gathered membership. The Hoskin Group / Liturgy Canada was formed.

- By the 1990s many, including some of its creators, were finding it dated and deficient in some respects, but for many reasons little energy could be found for further revision.