Books on Anglicanism

Information sources on Anglicanism from Trinity College Library

See this booklist posted by the diocese of Ottawa

"Anglican Communion" in Columbia Encyclopedia

A chronological survey

!Roman Britain: to about 400

Christianity

in Britain begins in the period when large parts of it are controlled by the

Roman Empire. We don't know who first brings Christianity there:

perhaps Roman administrators or soldiers or traders. Some Britons are

converted. The Britons are a Celtic people; so the influence of Celtic

Christianity on Anglicanism starts here. Medieval Anglicans such as Bede

will later claim Roman British Christianity as an important part of their

heritage. They'll tell stories of British Christian zeal, martyrdom,

mission, and controversy.

Christianity

in Britain begins in the period when large parts of it are controlled by the

Roman Empire. We don't know who first brings Christianity there:

perhaps Roman administrators or soldiers or traders. Some Britons are

converted. The Britons are a Celtic people; so the influence of Celtic

Christianity on Anglicanism starts here. Medieval Anglicans such as Bede

will later claim Roman British Christianity as an important part of their

heritage. They'll tell stories of British Christian zeal, martyrdom,

mission, and controversy.

!Medieval Anglicanism: 400–1529

With the immigration and/or invasion of the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and other Germanic peoples in the 400s, we can begin to speak of England (Angle-land) and an English Christianity. "Anglican" etymologically means English; the ecclesia anglicana, the English Church, is now being born. The medieval period can be divided into two sub-periods.

(1) Before 1066. Celtic Christianity flourishes spiritually. Anglo-Saxon Christianity develops after Pope Gregory I sends the missionary Augustine, called Augustine of Canterbury, among the English (597–604). Celtic Christianity generally seeks to remain independent of Roman influence; by contrast, Anglo-Saxon Christianity gravitates towards Rome. The differences are sometimes fanned into conflicts.

(2) After 1066. The Anglo-Saxon leadership of the Church is largely replaced after England is conquered by the Normans (former Scandinavian Vikings who have settled in what is naturally called Normandy, in northwestern France). Anglicanism becomes more Europeanized.

By the Reformation, the basis has been laid for the Anglicanism that we know, with its Celtic, English, Norman, and Roman influences (among others).

!The Reformation and Elizabethan periods (1529–1603)

During these seventy-five years or so a new religious spirit shapes

Anglican identity, and a

new

understanding of Anglican authority is forged. To speak generally, this

spirit is moderately Protestant, as seen in its commitment to Scripture, its

criticisms of papal authority, and the strong influence of lay leaders (king

or queen, Parliament, lay patrons of parishes). Significant

instruments of Protestant influence are the Prayer Books, the homilies of

the reign of Edward VI, the histories of John Foxe, the Thirty-Nine

Articles, and the writings of such divines as John Jewel and Richard Hooker,

who defended the Church of England against controversialists on both the

Roman Catholic and Puritan sides.

new

understanding of Anglican authority is forged. To speak generally, this

spirit is moderately Protestant, as seen in its commitment to Scripture, its

criticisms of papal authority, and the strong influence of lay leaders (king

or queen, Parliament, lay patrons of parishes). Significant

instruments of Protestant influence are the Prayer Books, the homilies of

the reign of Edward VI, the histories of John Foxe, the Thirty-Nine

Articles, and the writings of such divines as John Jewel and Richard Hooker,

who defended the Church of England against controversialists on both the

Roman Catholic and Puritan sides.

!The making of imperial Anglicanism (1603–1867)

In 1603 the crowns of England and Scotland are united in the person of the king — who is numbered James I in the English succession, and James VI in the Scottish succession. By now, too, Anglicans have reached the New World — they celebrate the eucharist at Frobisher Bay (1578), announce the establishment of the Church of England in Newfoundland (1583), and found Jamestown in Virginia (1607). With the founding of overseas British colonies and the rise of the British Empire, Anglican Christianity is extended to new cultures and races under the supervision of mission societies, and Anglicanism diversifies. The Episcopal Church in the United States becomes independent of English jurisdiction during the American Revolution (1776–1783). Globalization, colonialism, and indigenization raise fresh questions of Anglican identity and authority.

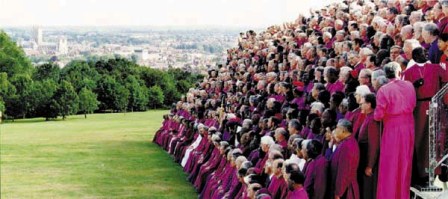

!The worldwide Anglican Communion (since 1867)

With

the important legal cases of Long v. Gray (1861) and Colenso v. Gray (1866),

which conclude that Anglican churches in self-governing colonies are

independent of the Crown and therefore of the Church of England, colonial

Anglican churches find themselves autonomous. Some fear that Anglicanism is

diversifying too much, and losing its English centre of gravity. Hoping to

tame these centrifugal forces, the ecclesiastical province of Canada

requests a meeting of Anglican bishops worldwide. The result is an episcopal

conference at Lambeth Palace, London, in 1867. This becomes the first in a

series of Lambeth Conferences held every ten years or so. the first Lambeth

Conference (1867). With this an Anglican communion is coming into existence,

as a worldwide family of autonomous churches. Throughout this period we see

pressures on the Anglican Communion in two directions. On the one hand we

see forces for greater closeness and cooperation: recent examples are the

Anglican Congress at Toronto in 1963, and the creation of the Anglican

Consultative Council and the Partners in Mission program in the following

decade. But on the other hand we see forces tending to undermine closeness

and cooperation: examples are the ordination of women, beginning in a

significant way in the 1970s; the displacement of the Prayer Book in the

1980s by forms of worship influenced by the Liturgical Movement; and strong

disagreements beginning in the 1990s about human sexuality. All three of

these developments raise profound questions about theological authority,

notably in the categories of Scriptural interpretation, tradition, and

doctrine.

With

the important legal cases of Long v. Gray (1861) and Colenso v. Gray (1866),

which conclude that Anglican churches in self-governing colonies are

independent of the Crown and therefore of the Church of England, colonial

Anglican churches find themselves autonomous. Some fear that Anglicanism is

diversifying too much, and losing its English centre of gravity. Hoping to

tame these centrifugal forces, the ecclesiastical province of Canada

requests a meeting of Anglican bishops worldwide. The result is an episcopal

conference at Lambeth Palace, London, in 1867. This becomes the first in a

series of Lambeth Conferences held every ten years or so. the first Lambeth

Conference (1867). With this an Anglican communion is coming into existence,

as a worldwide family of autonomous churches. Throughout this period we see

pressures on the Anglican Communion in two directions. On the one hand we

see forces for greater closeness and cooperation: recent examples are the

Anglican Congress at Toronto in 1963, and the creation of the Anglican

Consultative Council and the Partners in Mission program in the following

decade. But on the other hand we see forces tending to undermine closeness

and cooperation: examples are the ordination of women, beginning in a

significant way in the 1970s; the displacement of the Prayer Book in the

1980s by forms of worship influenced by the Liturgical Movement; and strong

disagreements beginning in the 1990s about human sexuality. All three of

these developments raise profound questions about theological authority,

notably in the categories of Scriptural interpretation, tradition, and

doctrine.