Some links for Anglican history and theology

The Eames Commission

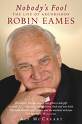

Robin Eames, primate of Ireland, reflects in September 2003 on the question of Anglican unity.

Press release, October 2003, announcing its appointment

Press release, December 2003, announcing its meeting schedule, agenda, and key questions

A correspondent for "Anglicans Online" describes progress as of September 2004

Press report and video resources from Episcopal News Service when the "Windsor report" is published at St. Paul's Cathedral, London, on October 18, 2004

The Windsor report, PDF version

The Windsor report, html version

Eames commission, public documents

Response of the Anglican Church of Canada, Primate's Theological Commission (the St. Michael report), as requested by General Synod; released May 6, 2005

Theologians of the Episcopal Church, at the invitation of the presiding bishop, respond with the book To Set Our Hope on Christ, available in pdf format, released June 21, 2005

Report on hearings concerning the Windsor Report held at the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, Columbus, Ohio, June 14, 2006

Numerous links to responses to the Windsor Report accumulated by the American Anglican Council, a group which holds a conservative position on the blessing of same-sex unions

An excellent article from the Financial Times, Dec. 16, 2005, on issues of Anglican identity. The author, John Lloyd, is the neoconservative editor of FT Weekend Magazine, and a former editor of the New Statesman

A challenge from Anglicans of the global south on Anglican unity, October 2005

Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams on "the only ground for unity in Christ," November 2005

Some Anglican primates from the southern hemisphere are disappointed in Williams' address

On May 28, 2003, an Anglican parish priest in east

Vancouver blessed a same-sex union,

with the permission of her

bishop and in conformity with the policy of her diocese, New Westminster.

On August 5, 2003, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in the

United States approved the election of Gene Robinson, an openly homosexual

priest, as bishop of New Hampshire. These two events stirred

considerable international controversy among Anglicans, and have exposed

entrenched disagreements, not merely about sexuality and human nature, but

also about the authority and interpretation of Scripture, the relation

between Church and society, the understanding of discipleship, the character

of the Church, and the constitution of the Anglican Communion.

Because the Anglican Communion is a family of self-governing churches and

has no instruments of global jurisdiction, it was not at all clear how

Anglicans, as a worldwide group, could process their disagreements.

with the permission of her

bishop and in conformity with the policy of her diocese, New Westminster.

On August 5, 2003, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in the

United States approved the election of Gene Robinson, an openly homosexual

priest, as bishop of New Hampshire. These two events stirred

considerable international controversy among Anglicans, and have exposed

entrenched disagreements, not merely about sexuality and human nature, but

also about the authority and interpretation of Scripture, the relation

between Church and society, the understanding of discipleship, the character

of the Church, and the constitution of the Anglican Communion.

Because the Anglican Communion is a family of self-governing churches and

has no instruments of global jurisdiction, it was not at all clear how

Anglicans, as a worldwide group, could process their disagreements.

Responding

to this controversy, the archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, announced

on October 29, 2003, that he had appointed a commission "to look at the life

of the Anglican Communion in light of recent events," to report to him in a

year's time. In other words, it was not to consider issues of

sexuality as such, but issues of communion among Anglicans. The

commission was chaired by Archbishop Robin Eames, primate of Ireland, and

was therefore commonly called the Eames Commission. It had

seventeen members, representing a spectrum of cultures, theological views,

church positions, and areas of expertise. It met three times, held

hearings, and finally, in October 2004, released its report. It

concluded that there were deep symptoms of a serious illness in the Anglican

Communion and that "there remains a very real danger that we will not

choose to walk together." It made recommendations

towards a healing of divisions and a strengthening of instruments of unity.

The report has been controversial, and has attracted both support and

criticism.

Responding

to this controversy, the archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, announced

on October 29, 2003, that he had appointed a commission "to look at the life

of the Anglican Communion in light of recent events," to report to him in a

year's time. In other words, it was not to consider issues of

sexuality as such, but issues of communion among Anglicans. The

commission was chaired by Archbishop Robin Eames, primate of Ireland, and

was therefore commonly called the Eames Commission. It had

seventeen members, representing a spectrum of cultures, theological views,

church positions, and areas of expertise. It met three times, held

hearings, and finally, in October 2004, released its report. It

concluded that there were deep symptoms of a serious illness in the Anglican

Communion and that "there remains a very real danger that we will not

choose to walk together." It made recommendations

towards a healing of divisions and a strengthening of instruments of unity.

The report has been controversial, and has attracted both support and

criticism.

A question of Anglican identity

The

controversies on sexuality represented by the diocese of New Westminster

and by Gene Robinson take us into the question of Anglican identity.

What does it mean to be an Anglican? Does it make sense to speak

of "Anglicanism", and if so, what is it? Is it

possible to distinguish between those theological affirmations,

liturgical expressions, and lifestyles which are clearly within

Anglicanism and those which are clearly outside? Who

decides?

The

controversies on sexuality represented by the diocese of New Westminster

and by Gene Robinson take us into the question of Anglican identity.

What does it mean to be an Anglican? Does it make sense to speak

of "Anglicanism", and if so, what is it? Is it

possible to distinguish between those theological affirmations,

liturgical expressions, and lifestyles which are clearly within

Anglicanism and those which are clearly outside? Who

decides?

There are also other paths into the question of Anglican identity.

- Spirituality, devotion. Many Anglicans seek to be loyal to the Anglican tradition, but aren't sure where to find it. They therefore seek to identify its norms.

- Concern for theological integrity. Stephen Sykes, in Integrity of Anglicanism (1978), argued that, as a matter of theological integrity, Anglicans needed to know what they believed. There are many styles of Anglican theology ─ liberal, conservative, radical, and feminist, intersecting sometimes with more protestant views, sometimes with more catholic ones. Sykes argued that the current fashion of simply trying to be comprehensive of all theological diversity reflected "a vested interest in refusing to think straight." Many Anglicans didn't know what they believed, and indeed many supposed that belief wasn't really very important anyway.

- Liturgical diversity. Until the 1960s, most Anglicans worldwide worshiped according to one of the two families of the Book of Common Prayer, the 1549 family and the 1552 family. Since then, with Liturgical Movement liturgies (such as the Canadian Book of Alternative Services), radical liturgies (such as the Canadian Alternative Eucharistic Prayers,1998), conservative catholic liturgies, charismatic services, local uses written by parish committees, Celtic liturgies, and informal services, there's no longer a common liturgical sense among Anglicans. It's easy for Anglicans to feel like strangers in their own church, and this may undermine a sense of communion.

- Cultural and ethnic diversity. Anglicanism is generally open to inculturating the gospel in its various host societies ─ that is, making use of symbols, language, music, architecture, art, and forms of thought that make sense in the local culture. With a host of various inculturations, however, Anglicans' sense of common identity can get lost.

- Interdenominational controversy. When Anglicans are criticized by others, they will often seek to show that Anglicanism has been misunderstood, and will give an alternative account of its identity. Note the Roman Catholic declaration Dominus Iesus, and this BBC summary of reaction by the archbishop of Canterbury among others.

But it's also possible to argue that the very question of Anglican identity can lure us into a kind of idolatry. In the end, why should we care about Anglicanism? It's merely one imperfect expression of Christian discipleship among others; and in the end it's Christ that's important, not Anglicanism. Here's Michael Ramsey in The Gospel and the Catholic Church (1936):

While the Anglican Church is vindicated by its place in history, with a strikingly balanced witness to the gospel, to the Church and to sound learning, its greater vindication lies in pointing through its own history to something of which it is a fragment. Its credentials are its incompleteness, with the tension and travail in its soul. It is clumsy and untidy; it baffles neatness and logic. For it is sent not to commend itself as the "best type of Christianity", but by its very brokenness to point to the universal Church wherein all have died.