Links and resources

Indian missions of the middle Atlantic states, from the Handbook of American Indians, 1906.

Should the Book of Common Prayer be translated into a language "so rude and uncultivated as the Indian"? Yes, says this 1842 preface to a Mohawk Prayer Book.

Pauline Johnson

From The Officers' Quarterly, 1995

From Dictionary of Canadian Biography

At McMaster University Archives; lots of links

Anglican missionaries to the Iroquois

"Iroquois" is the French term for an aboriginal confederacy which the English

called the Five

Nations.

The peoples of this confederacy called themselves the Haudenosaunee, "people of the Longhouse."

On European contact, the Five Nations were centred in what is now

upstate New York, along the Mohawk River west of Albany. The

nations were the Mohawk, Oneida, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga.

In the early 1720s they were joined by the Tuscarora, refugees from

Virginia and North Carolina, and since then their confederacy has been

called the Six Nations.

Nations.

The peoples of this confederacy called themselves the Haudenosaunee, "people of the Longhouse."

On European contact, the Five Nations were centred in what is now

upstate New York, along the Mohawk River west of Albany. The

nations were the Mohawk, Oneida, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga.

In the early 1720s they were joined by the Tuscarora, refugees from

Virginia and North Carolina, and since then their confederacy has been

called the Six Nations.

The Jesuits in New France had significant

missions among the Iroquois

beginning in the 1600s;

the Dutch, who controlled the Hudson River Valley from 1609 to 1664, made feebler attempts.

In 1664 New York fell

within the English sphere of influence. The quasi-independent mission

arm of the Church of England, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel,

sent missionaries to the Iroquois beginning in 1704.

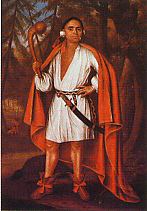

In 1710

four

Iroquois chiefs met Queen Anne at St. James' Palace in London,

sought military assistance against the French, and, with good strategic

sense,

In 1710

four

Iroquois chiefs met Queen Anne at St. James' Palace in London,

sought military assistance against the French, and, with good strategic

sense,

asked

to be properly instructed in religion, the "French Priests" having been "men

of Falsehood." (Contemporary

portraits of the four chiefs by Jan Verelst, including the one at

left, were given to the National Archives in Ottawa by Queen Elizabeth

II in 1977.) The queen had

a chapel constructed at Fort

Hunter, New York, in 1712. (The church was destroyed when the Erie

Canal was dredged, but the vicarage still stands.) She

also sent communion silver. Among the SPG missionaries who made their

mark were :

asked

to be properly instructed in religion, the "French Priests" having been "men

of Falsehood." (Contemporary

portraits of the four chiefs by Jan Verelst, including the one at

left, were given to the National Archives in Ottawa by Queen Elizabeth

II in 1977.) The queen had

a chapel constructed at Fort

Hunter, New York, in 1712. (The church was destroyed when the Erie

Canal was dredged, but the vicarage still stands.) She

also sent communion silver. Among the SPG missionaries who made their

mark were :

- William Andrews, who served from 1712 to 1718. He learned the Mohawk language, and two Dutch Reformed Christians of his acquaintance translated parts of the Book of Common Prayer into Mohawk (published 1715).

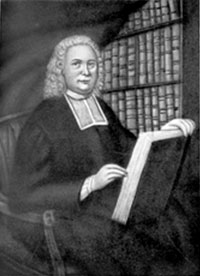

- Henry Barclay, a native-born New Yorker and Yale graduate,

pictured left, who

served from

1734

to 1746. By 1735 he has sufficiently mastered Mohawk to teach

children to read and write in their own language. By about 1742 he

is said to have baptized almost all the Mohawks. He was the

principal translator of a new Prayer Book in Mohawk published in 1769.

1734

to 1746. By 1735 he has sufficiently mastered Mohawk to teach

children to read and write in their own language. By about 1742 he

is said to have baptized almost all the Mohawks. He was the

principal translator of a new Prayer Book in Mohawk published in 1769. - John Stuart, a thirty-year-old Pennsylvanian, who served Fort Hunter from 1770 until 1778, when he was arrested by American rebels. With his friend Joseph Brant, he translated St. Mark's gospel into Mohawk. In 1781 he was exchanged for an American prisoner and made his way to Quebec. In 1785 he moved to Cataraqui, where he became first rector of St. George's, Kingston, and "the father of Anglicanism in Upper Canada." His ministry included pastoral care of Mohawk refugees in Deseronto, and he also travelled to visit the Iroquois of the Grand River territory.

Sir William

Johnson (1715-1774) came to the Mohawk Valley in 1738 to oversee an

uncle's estate, and became a successful businessperson, sometime military

commander,

and

government Indian agent. In his last thirty years he appears to have

"gone native," as was said, adopting Mohawk clothing, hairstyle, and habits,

and taking

Gonwatsijayenni (Mary or Molly Brant, Thayendanegea's sister) as his

wife by Indian ceremony (it was believed). As for Molly Brant, she had

attended an Anglican mission school as a child, and she remained a devout

Anglican all her life. In her last years she attended St. George's,

Kingston, where she "sat in an honourable place among the English."

and

government Indian agent. In his last thirty years he appears to have

"gone native," as was said, adopting Mohawk clothing, hairstyle, and habits,

and taking

Gonwatsijayenni (Mary or Molly Brant, Thayendanegea's sister) as his

wife by Indian ceremony (it was believed). As for Molly Brant, she had

attended an Anglican mission school as a child, and she remained a devout

Anglican all her life. In her last years she attended St. George's,

Kingston, where she "sat in an honourable place among the English."

Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant)

Thayendanegea (1743-1807) was sponsored to a Christian school in

Connecticut by Sir William Johnson, and at about age 19 "began truly to

love our Lord Jesus Christ," according to his schoolmaster. He

spoke at least three Iroquois languages as well as English fluently.

He married an Oneida woman in 1765, and on her death in 1771 went to

live with John Stuart, with whom he published a translation St. Mark's

gospel, a Mohawk commentary on the catechism, and a history of the

bible. In 1775 he was chosen a chief. He led warrior

parties for the British during the American Revolution, and "emerges in

the official dispatches as the perfect soldier," according to the

Dictionary of Canadian Biography (linked above). After the

war, he worked hard and not entirely successfully to maintain the unity

of the Iroquois confederacy and to extract justice for his people from

the Americans and British. He secured a large grant of land from

William Haldimand, the

governor

of Canada, in 1784. He helped arrange a schoolmaster and church

there, but was unsuccessful in having a minister appointed.

St. Paul's Church,

was built in 1785, and dedicated in 1788 by John Stuart. It is the

oldest Protestant church in Ontario. In 1904 it received the

status of a royal chapel. Brant made a fresh Mohawk translation of

the Prayer Book. He critiqued many aspects of white culture as

inconsistent with Christianity, including social inequality, the

manipulation of justice by "enterprising sharpers," and harsh prisons.

“Cease ... to call other nations savage, when you are tenfold more the

children of cruelty than they,” he wrote.

governor

of Canada, in 1784. He helped arrange a schoolmaster and church

there, but was unsuccessful in having a minister appointed.

St. Paul's Church,

was built in 1785, and dedicated in 1788 by John Stuart. It is the

oldest Protestant church in Ontario. In 1904 it received the

status of a royal chapel. Brant made a fresh Mohawk translation of

the Prayer Book. He critiqued many aspects of white culture as

inconsistent with Christianity, including social inequality, the

manipulation of justice by "enterprising sharpers," and harsh prisons.

“Cease ... to call other nations savage, when you are tenfold more the

children of cruelty than they,” he wrote.

Emily Pauline Johnson-Tekahionwake (1861-1913)

Among the best known of the Mohawks of the Grand River is Pauline Johnson-Tekahionwake, a very popular, widely published, best-selling poet and author who went on recital tours in North America and Britain between 1892 and 1910. Her great-grandfather's English-language surname Johnson was given him at baptism by Sir William Johnson. Her father, who became a chief, began his career as a translator for the Anglican church on the reserve. Her mother was an English woman who raised her children "as Indians in spirit and patriotism," as Pauline later wrote. An uncle by marriage was the Anglican minister on the reserve in the 1850s. She grew up on the Chiefswood estate on the Grand River (which was bequeathed to the Six Nations Band Council). She had little formal education, but read voraciously from the family library. Religious themes figure rather prominently in her writing, including her short story "As it was in the beginning," which adopts the persona of a young Cree girl who is sent to an Indian residential school. Tekahionwake's reputation suffered after her death; she has not quite belonged either to native Canadian or European-Canadian literature; and her romantic tendencies have not appealed to academics. However, after receiving favourable notice in essays by Margaret Atwood in the 1980s, she began to be recovered as a post-colonial, feminist, native author who effectively critiqued the conventions and prejudices of her time.