Historical geography

Link to a map of Roman Britain

1. Roman Britain. “Anglican” means “English”. The “Angles” after whom England is named didn’t come into what we now call England until the fifth century, and the name England didn’t appear until about the ninth century, but the territory England now occupies knew Christianity in Roman times. The people who lived there when the Romans conquered it were Celtic, and we call them Britons. Rome removed its armies from Britain in 409 (the year before the great Sack of Rome by “barbarian” armies). That is the end of Roman Britain, though of course British Christianity continued.

2. Origins of England. Angles, Saxons, and other Germanic peoples came to Britain — immigrated, invaded, or were invited (or some combination of these) — in the fifth century. Signs of British culture decline and are replaced by signs of Germanic cultures, because of intermarriage and cultural assimilation, or conquest, or gradually shifting population patterns (or some combination of these). Anglo-Saxon kingdoms sprout up.

3. Celtic Christianity. It appears that British Christians migrated west to Wales and Ireland, and south to Brittany (present-day France), and north to Strathclyde in present-day Scotland. In many of these places the customs of Celtic Christianity survived into the twelfth century.

4. Scotland. North of England lies present-day Scotland, called Caledonia in Roman times (though this territory was never conquered by the Romans). In these times it was inhabited by peoples called Picts. In the sixth century, invaders from northern Ireland called “Scotti” came to occupy the northern part of this territory, while germanic invaders from England came to occupy the southern part of this territory. Northumbria became disputed border territory. The pictish, germanic, celtic, and scandinavian peoples of this northern area were united in the new kingdom of Scotland after the battle of Carham in 1018.

Christianity in Roman Britain

1.

Planting of Christianity. Who began evangelizing Britain,

and when, are unknown. There have been legends that:

1.

Planting of Christianity. Who began evangelizing Britain,

and when, are unknown. There have been legends that:

● Joseph of Arimathea founded a church at Glastonbury in the first century, and that he brought with him the holy grail of Arthurian legend; or that

● Britain was settled by the ten lost tribes of Israel after the Assyrian invasion of 722 BC (a view promoted by "British Israel" and by the twentieth-century American evangelist Herbert W. Armstrong); or that

● Jesus as a youth visited Britain with his uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, as alluded to in Blake's "Jerusalem."

2. Alban. The story of Britain’s proto-martyr, Alban, is given in Bede (H.E., I, vii). It is generally regarded as based in fact. The martyrdom is variously dated in the early 200s, in the 250s during the Decian persecution, or in the early 300s under the persecution of Diocletian. The present-day abbey and cathedral of St. Alban’s, north of London, is supposed to be where Alban was executed.

3. Archaeology. There are remains of Christian house churches and church buildings. The British Museum displays a floor mosaic from a third- or fourth-century church found in Dorset in 1963, featuring the head of Christ along with Christian symbolism.

4. Pelagius. A monk from the British isles who taught at Rome in the years around 400. Pelagianism is usually described as holding that people can take the initial step towards their salvation (underestimating God’s grace, overestimating human capacity). Some say that it’s better described as holding that, at conversion, Christians can rise above sin. Either way, the western Church disowned it.

5. Missionaries.

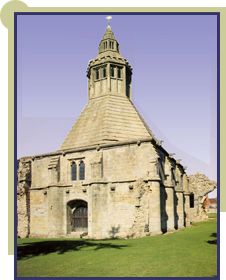

- Ninian. First half of the fifth century? Founded a church from which he evangelized the Picts of what is now Scotland.

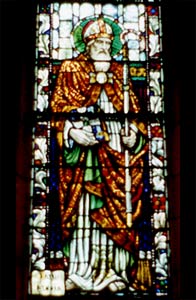

Patrick,

patron saint of Ireland. About the same time? Evangelized

the Irish; left two significant writings.

Patrick,

patron saint of Ireland. About the same time? Evangelized

the Irish; left two significant writings.

6. Gildas. A British Christian who wrote “The Ruin of Britain” around the 540s, the only ancient history of the Celts. He connected the conquest of the Britons by the Germans with the corruption of the Church’s leadership, and urged reform.

7. Monasteries. British Christians were influenced by the style of monasticism connected with Martin of Tours (in present-day France) in the fourth century. This monasticism set higher demands than the more successful, and probably more humane, monasticism connected with St. Benedict two centuries later. Many of the Celtic saints were founders of monasteries. They include : —

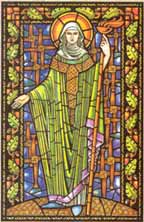

Brigid

(Bride), d. c. 523, abbess of Kildare, a second patron saint of Ireland.

According to tradition, her parents were baptized by Patrick.

Brigid

(Bride), d. c. 523, abbess of Kildare, a second patron saint of Ireland.

According to tradition, her parents were baptized by Patrick. - Columba, d. 597, an Irish monk, and founder of the important monastery at Iona (in the Inner Hebrides off northwest Scotland), a centre for missionary activity in Scotland.

- David, d. 601, an extreme ascetic with a monastery at Mynyw; patron saint of Wales.

- Columbanus, d. 615, an Irish monk who established monasteries in present-day France, Switzerland, and Italy. Spread and popularized the Celtic penitential system, which regularized absolution for sin committed after baptism, and which grew into the requirement of auricular confession as decreed in 1215.

8. Themes of Celtic Christianity.

- Organized around monasteries rather than dioceses; hence more lay than clerical, led more by ascetics than by administrators

- Highly Scriptural; particularly connected with the copying of magnificent illuminated manuscripts of Scripture

- Produced much poetry and hymnody (e.g., “Be thou my vision,” “St. Patrick’s Breastplate”)

- Monasteries were typically in rugged natural spots, and poetry reflects a love of nature

- Very large commitment to evangelism and mission

9. Characteristic Anglican themes as seen in the Roman British period.

- The tension between gospel and culture in the Christian life; in particular, the Christian’s conflicting claims of allegiance between church and state; seen in Alban, and in the many Anglican martyrs recognized in the Calendar.

- But also, the value of expressing the gospel in the signs and artistic forms of the host culture, as seen in early British Christian art work.

- Disputes about the relative weights to be assigned to grace and free will in the Christian life; and perhaps a tendency of Anglicans to set more value on virtuous character, good order, and spiritual discipline than some other varieties of Christian.

- A recognition that the Church is committed to mission, though not necessarily an agreement as to what form that mission should take.

- A concern of Anglicans for their history, and a sense that the study of history may help them see the need for reform.

- Poetry.

- Love of nature.

ALH