I. Anglicans in North America before the SPG

June 24, 1497: Jean Cabot discovers Canada

Sept 4, 1578: 1st Anglican eucharist in North America

1583: Colony in Newfoundland with Anglican establishment: unsuccessful

1607: Jamestown, Virginia, founded with Anglican establishment

1619: C of E formally established in Virginia

1641: Massachusetts becomes first British colony to recognize slavery as a legal institution; Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia, New York, New Jersey follow

1669: Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina. This establishes the C of E but grants full liberty of religion (including Jews)

1670: Hudson's Bay Company chartered. Receives ownership of all lands draining into Hudson's Bay.

1682: St. Philip's, Charleston, built

1686: Charter of Massachusetts colony revoked; C of E clergy appointed

1689: Trinity Church, NY, consecrated

1693: College of William and Mary chartered

1699: St. John's, Newfoundland has congregation and pastor

II. Anglicans in North America 1701-1793

1701: SPG is founded. Will send 1597 missionaries to Canada 1701-1900. Continues to assist Canadian Church through 1940

1703: C of E established in Maryland

1710: Port-Royal (Acadia) permanently captured by the British; renamed Annapolis Royal; Anglican garrison chapel operates (1713, Treaty of Utrecht)

1735: John Wesley arrives in Georgia as SPG missionary

1749: Halifax founded; 1750: St. Paul, Halifax, built, oldest Anglican church building in Canada

1755: Expulsion of the Acadians

1763: Treaty of Paris; France cedes to Britain its possessions North America east of the Mississippi. First royal instructions to Governor Murray provide for the establishment of the C of E in Canada

1772: Anglican evangelical Biblical critic Granville Sharp wins the Somerset case; slavery becomes illegal in England

1774: Quebec Act

July 4, 1776: Declaration of Independence; American Revolutionary War begins

1783: Treaty of Paris ends the Revolutionary War; loyalists evacuated; Protestant Episcopal Church in the U.S.A. formally organized

Nov. 14, 1784: Samuel Seabury consecrated bishop by nonjuring Scottish episcopalians

Feb. 14, 1787: William White and Samuel Provoost consecrated bishops for the Episcopal Church, U.S.A.

Aug. 12, 1787: Charles Inglis consecrated bishop of Nova Scotia at Lambeth

1787: New England Company begins first Indian Residential School, Sussex Vale (near Saint John), NB

1788: King's College established in Windsor, NS

1791: Constitutional Act creates Upper and Lower Canada; sets aside the clergy reserves; empowers creation of Anglican rectories. Jacob Mountain appointed bishop of Quebec

III. Anglicans in British North America 1791-1867

1793: Slavery Act of Upper Canada, the first legislation in the British Empire for the abolition of slavery

1812: John Strachan arrives in York

1820: John West begins first Indian residential school in the Canadian West, at Red River.

1828-1829: Test Acts increase religious toleration in England.

July 14, 1833: John Keble preaches the Assize Sermon, the traditional date for the beginning of the Anglo-Catholic Revival

1836-1837: Registration Acts in England recognize non-Anglican marriages; similar legislation follows in the BNA colonies

1845: John Medley, first bishop of Fredericton, the first Tractarian bishop

1846: Repeal of the Corn Laws

1847: Principle of responsible government first applied in BNA (in Nova Scotia)

1849: Robert Baldwin, an evangelical Anglican, wins legislative assent to the Baldwin Act, secularizing the Anglican King's College, Toronto

1851: John Strachan, a high-church Anglican, founds Trinity College, Toronto, to take the place of King's

1854: Clergy Reserves secularized

1863: Long v. Gray establishes the independence of Anglican churches in self-governing British colonies

1863: Henry Budd, a Cree, becomes the first North American Indian to be ordained in the Church of England

1864: Colenso v. Gray vacates coercive jurisdiction of Anglican bishops in British colonies

1865: Robert Machray consecrated second bishop of Rupert's Land

1867: Canadian Confederation. First Lambeth Conference

Political background

1. In the late fifteenth century, European seafaring powers began exploring the new world. Sometimes chaplains went on board their ships. Sometimes they established outposts, garrisons, settlements, or even colonies with a Christian presence.

On board the English ships there were sometimes Anglican chaplains. The calendars of commemorations in the BCP and BAS identify September 4, 1578, as the date when Robert Wolfall, ship's chaplain to Martin Frobisher, celebrated the eucharist for the first time in what is now Canada. That happened at Frobisher Bay.

3. In the seventeenth century English political and economic theorists took the view that controlling trade, and establishing and protecting colonies, were good things. This was called "mercantilism". Mercantilism was implemented by the Navigation Acts and the Board of Trade. England established colonies in several places, including North America. Colonies were supposed to provide natural resources for manufacture in England. They were not allowed to trade directly with foreign powers. Colonists sometimes found this environment a repressive one.

Typically, the Church of England was established in English colonies overseas (though sometimes England gave colonies to non-Anglicans who might make other religious provisions). From the English government point of view, the Church built moral character and provided pastoral care for the colonists. From the colonial point of view, the Church was sometimes identified as part of the repressive political apparatus of social control.

3.

We have already heard about "the Glorious Revolution” of 1688–1689,

when Parliament threw out James II, a Roman Catholic king, and invited

William and Mary (the latter is pictured here) as the new king and queen.

Of course this was highly controversial. Did Parliament really have

authority to get rid of kings? This question was intimately connected

with another: should non-Anglican religions be tolerated? Two parties

emerged.

3.

We have already heard about "the Glorious Revolution” of 1688–1689,

when Parliament threw out James II, a Roman Catholic king, and invited

William and Mary (the latter is pictured here) as the new king and queen.

Of course this was highly controversial. Did Parliament really have

authority to get rid of kings? This question was intimately connected

with another: should non-Anglican religions be tolerated? Two parties

emerged.

a. One group was called "tories" (as a political name) or "high-church" (as an ecclesiastical name). They affirmed the divine right of kings, the duty of passive obedience on the part of subjects, the importance of church establishment in the English constitution, and the importance of episcopacy and sacraments, being characteristics which distinguished Anglicans from other Protestants.

b. The other group was called "whigs" or "low-church". They affirmed the opposite.

These terms have changed meaning several times over the centuries, but these were the first uses.

4. Here are the kings and queens of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries:

- George I 1714–1727

- George II 1727–1760

- George III 1760–1820

- George IV 1820–1830 (this period 1714-1830 is the "Georgian" period)

- William IV 1830–1837, Victoria 1837–1901.

Here are the governments: Whigs dominated under George I and George II (when toryism was considered slightly disloyal). Tories dominated 1760–1830.

The Enlightenment

1. From the mid-seventeenth century, scientific discovery was charateristic of English intellectual life. Isaac Newton (1642–1727) is the representative figure of this development. The Royal Society (1662) is the representative institution.

2. From this date there grows the age of "Enlightenment”, a turning-point in history, and often regarded as the origins of modernity. From this point, in the West, Christians had to decide whether and how to connect their faith with scientific discovery.

3. A very influential whiggish intellectual of this early scientific culture was John Locke (1632–1704). He was known for arianism in religion, and the social contract theory in politics. He wrote the constitution for the American colony called Carolina. He took the view that government is established, not from above by conquerors and kings and queens, but from below, by the people. His views influenced the American revolutionaries of 1776, who decided that, by their poor government, the king and government of England had breached the original social contract, and that they had the right to institute a new government instead.

4. In English church affairs, the corresponding intellectual movement was "Latitudinarianism". This meant that Christians should honour a wide latitude of doctrine and practice. Latitudinarians assigned considerable religious authority to reason (as opposed to revelation) and urged charity in matters of church doctrine and discipline ("charity is greater than rubrics").

Colonies before the American Revolution

1. Newfoundland became a fishing station in the 1490s with occasional Anglican presence during the summer season. In the 1580s Sir Humphrey Gilbert attempted a settlement there, and the Church of England was formally established. But the settlement didn't last. In 1699 a settled minister was sent to St. John's and a congregation developed. This is the oldest Anglican congregation in what is now Canada.

2. The thirteen American colonies were established at various times beginning with Virginia in 1607. The Church of England was established in the southern colonies. Congregationalism came to be established in the northern colonies. Toleration of religion was the rule in the middle colonies, plus Rhode Island. As the established church, the Church of England ran local government, received government support, and was in some measure controlled by the government. There were no bishops in North America, and the result is that lay leaders became highly influential in American Anglicanism, as they still are.

The Anglican Church in the "southern" colonies was characterized by a "low church" (latitudinarian) ethos, strong church involvement in local government, and a high degree of lay control often exercised through vestries.

The Anglican Church in the "northern" colonies was characterized by a "high church" (tory) ethos, a strong sense of clerical authority, and hostility towards non-episcopal churches.

A controversy about the appointment of bishops for America mbittered relations among Anglicans, and between Anglicans and non-Anglicans, before the Revolutionary War.

3.

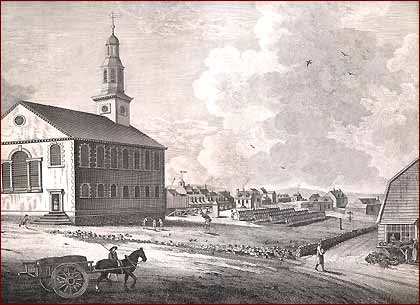

Nova Scotia came partly into English hands after 1710, and Anglican

congregations began to come into existence. The oldest Anglican

church building in what is now Canada is St. Paul's, Halifax (1750).

3.

Nova Scotia came partly into English hands after 1710, and Anglican

congregations began to come into existence. The oldest Anglican

church building in what is now Canada is St. Paul's, Halifax (1750).

4. Quebec had a very small Anglican presence before the American Revolution. What is now Ontario had almost no European population before the American Revolution.

The Anglican Church before the Revolution

1. Thomas Bray, an Anglican priest who had served as a bishop's commissary in Maryland, recognized a huge need for mission assistance for the Church in America, and worked to create the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (S.P.G.) (1701). This had powerful and wealthy friends, and it supported most Anglican clergy and churches in the thirteen colonies before the American Revolution, and most Anglican clergy and churches in what is now Canada for many years afterwards. It continued to support Anglican churches in Canada until as late as 1940.

Significant characteristics of the SPG include:

- A high-church ethos.

- A well developed systemto ensure the accountability of SPG missionaries. This system sometimes conflicted with the jurisdiction of colonial bishops.

- Provision for regional conferences of clergy. These would grow into the diocesan conventions of the Episcopal Church in the U.S., which in turn were the model for diocesan synods in Canada.

2. Anglicans in the southern colonies tended to be whiggish and low-church, those in New York and New England tory and high-church. Southern Anglicans tended to be content not to have bishops, but New England Anglicans sought diligently to have American bishops appointed. Many at the time (including John Adams, later president of the United States) thought that the aggressive campaign among some Anglicans for Anglican bishops was a principal cause, or perhaps even the major cause, of the American Revolution. Bishops were seen as agents of English political repression.

British North America 1783- 1867

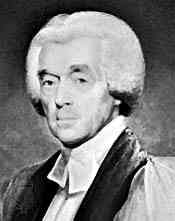

1.

Anglicans, and everyone else, had to take sides during the American

Revolution. The choice was to be a "patriot" or a "loyalist".

Most southern Anglicans became patriots. Most northern Anglicans

became loyalist. The most noteworthy Anglican patriot was William

White (1748–1836), chaplain to the Continental Congress and later

the first presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States.

The most noteworthy Anglican loyalist was Charles Inglis (1734–1816),

rector of Trinity Church, New York, and later first bishop of Nova Scotia

(pictured left).

1.

Anglicans, and everyone else, had to take sides during the American

Revolution. The choice was to be a "patriot" or a "loyalist".

Most southern Anglicans became patriots. Most northern Anglicans

became loyalist. The most noteworthy Anglican patriot was William

White (1748–1836), chaplain to the Continental Congress and later

the first presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States.

The most noteworthy Anglican loyalist was Charles Inglis (1734–1816),

rector of Trinity Church, New York, and later first bishop of Nova Scotia

(pictured left).

2. After the Revolution, many loyalists, including a significant number of Anglicans, made their way north. Thus a large English population, and a large Anglican Church presence, came to exist in Nova Scotia and what is now Ontario, and also in what is now New Brunswick and Quebec.

We're reading William White's reflections in class. White was instrumental in re-organizing American Anglicanism after the Revolution as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (PECUSA). With the permission of the U.S. government and the governments of the affected states, White and others were consecrated Anglican bishops in the Church of England. A New England priest, Samuel Seabury, had already been consecrated bishop by bishops in the Episcopal Church of Scotland, which was not recognized in England, although its bishops were in the historic succession. Tensions between high-church New Englanders and low-church others had to be addressed in the founding convention of the new Episcopal Church (and it wasn't easy).

3. Some very important Anglican churches were supported by the government, but most were supported by English mission societies. The most important ones were the S.P.G. and the Church Missionary Society, which to a large degree represented the high-church and evangelical wings of the church, respectively. A third society which changed its name several times but which can be called the Colonial and Continental (Col. and Con.) was also important, and was ultra-evangelical.

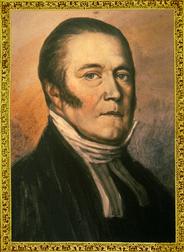

4.

A number of politicians as well as the early Anglican bishops, especially

Jacob Mountain in Quebec and John Strachan in Toronto (pictured left),

favoured an established Anglican church. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick,

and Prince Edward Island did establish the Church of England in their

territories by statute. In Quebec, with the large Roman Catholic

presence, it was not politically feasible, and it would certainly have

been resisted in what is now Ontario as well, where perhaps only 20% of

the settlers were Anglican. We read Strachan's sermon on the death

of Mountain as an important statemetn of the establishment ideal.

4.

A number of politicians as well as the early Anglican bishops, especially

Jacob Mountain in Quebec and John Strachan in Toronto (pictured left),

favoured an established Anglican church. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick,

and Prince Edward Island did establish the Church of England in their

territories by statute. In Quebec, with the large Roman Catholic

presence, it was not politically feasible, and it would certainly have

been resisted in what is now Ontario as well, where perhaps only 20% of

the settlers were Anglican. We read Strachan's sermon on the death

of Mountain as an important statemetn of the establishment ideal.

5. Anglicanism was established by statute in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, and had a certain quasi-established status in Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec). In Canada the Church of England received from the Crown the gift of a huge amount of land, called the clergy reserves. This was almost worthless at first, but it was intended to become a valuable endowment. Also, Anglican clergy had something approaching a monopoly on the right to perform marriages (along with Roman Catholics, of course).

6. The establishment ideal began declining in the 1830s, and most of the last trappings of church establishment disappeared by the early 1860s. Reasons include:

- English legislation increasing religious toleration in the late 1820s and early 1830s

- A greater number of non-Anglicans in the provincial legislative assemblies.

- The decline of mercantilism (it began to be replaced by capitalism, which preferred free markets, not protected markets, and which tended to a similarly non-protectionist mentality in matters of religion).

- The achievement of "responsible government" by British North American provinces, which led to similar patterns of self-government by Anglicans.

- Tractarianism

(the Anglo-Catholic movement), which disliked the establishment ideal,

since it seemed to subordinate church to state.