The Americas

WYH2003HS Spring 2003-- April 1

Links

A very brief overview of "contact and conquest in early America", by Patrick Minges, a recent Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary

A somewhat longer survey of early American colonialism, by Wayne Ellwood, from the New Internationalist, 1991

A history of the Jesuits from Prof. Joseph MacDonnell, Fairfield Univ., Fairfield, Conn.

A history of Jesuit missions mainly in Argentina and Paraguay, from an Argentine on-line travel guide

Pictures and information about the Jesuit province of Paraguay, 1609-1768, from an "Argentina for tourists" site (lots of annoying pop-ups here, though, and you may not be able to get back here)

Production notes for the Mission

NY Times review of The Mission

A biography of Las Casas, from Darren Provine, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ

"The Legacy of Las Casas", written in 1974 by Benjamin Keen, an historian at the University of Northern Illinois

Las Casas from the (old) Catholic Encyclopedia

We're reading some Jonathan Edwards this week. Here's lots of information about Jonathan Edwards from the website for the Yale edition of his works.

There are lots of websites for U.S. colonial history, too many to survey. Here's one for some primary sources. From the department of history, University of Colorado, here's lots of other links to get you started.

The European division of the Americas

- In the fifteenth century, first Portugal and then Spain began sending ships around the world, with a view to conquest, treasure, trade, and colonization. For the Americas, everyone knows the date 1492, when the Italian Christopher Columbus, sailing for Spain, made landfall in the West Indies and began the Spanish colonial era in America.

- Spain claimed the West Indies, most of South America (except Brazil), Central America, Mexico, Florida, and much of what is now the U.S. Southwest and California.

- Spain and Portugal, first off the mark among European countries in the Americas, were both Roman Catholic, and asked the Pope to help them decide their respective territorial jurisdictions. In 1493 the Pope drew a line from the North Pole to the South Pole, west of the Azores, and gave the Spanish the land to the west, and the Portuguese the land to the east. The powers agreed in the following year to move the line further to the west, so that when Brazil was discovered in 1500, it was given to the Portuguese.

- England's American empire began (some unsuccessful ventures in Newfoundland to one side) in 1607 at Jamestown, Virginia, and "New England" in 1620.

- France's American empire began (Cartier, in 1534, to one side) with Champlain's voyages in the seventeenth century. The first mass in Canada was celebrated in 1615 in Montreal.

Today we're considering Spanish America in the lecture, and British America in the tutorial. We've already taken a look at French America.

The Spanish American Church

- For reasons not particularly flattering to the Spanish conquerors or "conquistadores", Spain conquered the aboriginal peoples of the New World very quickly, through a combination of such tactics as massacre, threats, bribery, and intrigue. By 1515 the West Indies were Spanish. By 1521 the Aztecs were under Spanish domination. By 1536 the Incas were under Spanish control too.

- Priests and friars (and, later, Jesuits) accompanied the conquerors. Many served as chaplains to the conquerors. Some sought to minister to the aboriginals. The diocese of Santo Domingo was established in 1511, the first Mexican diocese in 1525.

- The conquerors sought to use the native peoples as slaves or virtual slaves, initially under the cruel "encomienda" system: colonists could require labour from the Indians, in exchange for (what laughingly passed for) protection and Christian instruction. Most clergy were happy with this system.

Some clergy, however,

protested. The first was Antonio de Montesinos in a famous sermon in

1511 which was bitterly received. The most systematic, courageous, and

brilliant protest came from Bartolomé de las Casas

(1474-1566), who is pictured right, and about whom more can be found

in the links to the left. He won the ear of Cardinal Ximenes and was

made Protector General of the Indians. After years of often discouraging

politicking, he was able to persuade the emperor Charles V to end (or

virtually to end) the encomienda system in 1542.

Some clergy, however,

protested. The first was Antonio de Montesinos in a famous sermon in

1511 which was bitterly received. The most systematic, courageous, and

brilliant protest came from Bartolomé de las Casas

(1474-1566), who is pictured right, and about whom more can be found

in the links to the left. He won the ear of Cardinal Ximenes and was

made Protector General of the Indians. After years of often discouraging

politicking, he was able to persuade the emperor Charles V to end (or

virtually to end) the encomienda system in 1542.- No significant effort was made to build up an indigenous ministry. A papal bull of 1576 permitted the ordination of mestizos or half-castes, but still not aboriginals. The first three Indian priests were not ordained until well after our period, in 1794.

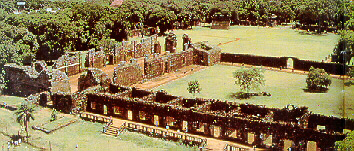

The

most famous frontier missions were those of the Jesuit "Province

of Paraguay", beginning in 1610, with twenty-three mission communities

by 1623. These communities were called "reductions" (reducciónes),

typically designed with a fine church at the centre, rows of houses,

land to cultivate, and buildings for light industry (a plan similar

to the French Jesuit mission at Sainte-Marie in Canada). Literature

was produced in the Guarani language. The illustration is the ruins

of one of the Jesuit missions. The reducciónes suffered frequent

raids, winked at by the Portuguese secular authorities, until the king

of Portugal protected Jesuit regions in 1641. The story of the end of

the missions in the 1750s is told in the film The Mission (1986),

about which further information is linked left. By then the Portuguese

government was impatient with protecting the native people, and equally

impatient with supporting the Jesuits. Portuguese soldiers massacred

hundreds of Indians in 1756, and the Portuguese government drove the

Jesuits out of the territory in 1759.

The

most famous frontier missions were those of the Jesuit "Province

of Paraguay", beginning in 1610, with twenty-three mission communities

by 1623. These communities were called "reductions" (reducciónes),

typically designed with a fine church at the centre, rows of houses,

land to cultivate, and buildings for light industry (a plan similar

to the French Jesuit mission at Sainte-Marie in Canada). Literature

was produced in the Guarani language. The illustration is the ruins

of one of the Jesuit missions. The reducciónes suffered frequent

raids, winked at by the Portuguese secular authorities, until the king

of Portugal protected Jesuit regions in 1641. The story of the end of

the missions in the 1750s is told in the film The Mission (1986),

about which further information is linked left. By then the Portuguese

government was impatient with protecting the native people, and equally

impatient with supporting the Jesuits. Portuguese soldiers massacred

hundreds of Indians in 1756, and the Portuguese government drove the

Jesuits out of the territory in 1759. - In Rome the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith was established for missionary work in 1622. A missionary seminary was founded in Paris in 1663. Increasingly secular clergy became more important in the Spanish American mission than the friars and Jesuits.