Summary

From a European point of view, the period from 1755 to 1815 was marked by a series of wars involving the English and French Empires, in which First Nations figured as allies of one side or another. Things looked different from a First Nations perspective. First Nations were fighting to protect their land, people, trade, and independence. They formed and changed alliances, or pronounced themselves neutral, for strategic reasons. Christianities sometimes supported, sometimes mitigated, and sometimes challenged that process. First Nations understandings of their goals and strategies were often shaped by the wisdom of First Nations prophets and spiritual leaders that in turn was influenced by Christianities: examples discussed here are Neolin (Lenape), Tenskwatawa (Shawnee), and Handsome Lake (Seneca). As always, despite the preferences of settler missionaries, First Nations Christianities didn't exclude traditional practices and identities, although they sometimes reinterpreted or reformed them. Racial categories were increasingly used to construct the relationship between settler and Indigenous peoples, and their religions. Compared with the actual complexities of settler–Indigenous relations, it was so easy to deal with just two categories, "white" and "Indian:" you knew exactly who your enemy was. Offsetting that tendency, however, was an intercultural engagement that could blur identities and that often hybridized Christianities. At the end of the period, as a result of mlitary, economic, and demographic changes, settler colonialism was increasingly able to marginalize and repress First Nations.

Outline of this webpage

- Overview of dates

- Primary sources

- Protestants before 1776 (Mohawks; Moor's Charity School; Oneida)

- The Royal Proclamation (Land disputes; the Ohio; race; French and Indian War; Neolin; Pontiac's Rebellion; the Royal Proclamation of 1763; the Treaty of Niagara of 1764; the Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1768)

- Joseph Brant

- The Revolutionary War; refugees; dispossession

- Acadia

- Protestants and the land 1760–1815

- The War of 1812 (Tenskwatawa, Tecumseh, First Nations warriors)

Overview of dates

Some dates

- 1704: In desultory fashion, the "SPG" of the Church of England begins a mission to the Mohawk of New York. For decades the missionary is located in Albany and mainly pastors settlers there.

- 1710: Four so-called Mohawk kings are received by Queen Anne in England. She provides the Mohawks with a church building and sends them a silver communion set (now divided between the Six Nations of the Grand River and Tyendinaga).

- 1715: The Anglican Book of Common Prayer is published in the Mohawk language, the first of several editions.

- 1742: Mohawk catechists and schoolmasters are apparent as the infrastructure of the Anglican mission.

- 1742: William Johnson, a trader living north of the Mohawk River, is made an honorary Mohawk sachem.

- 1744: King George's War (to 1748).

- 1749: Father LeLoutre's War (Acadia), to 1755; Nova Scotia offers a bounty on Mi'kmaq scalps.

- 1753: The Iroquois Covenant Chain, an agreement dating back to the first days of British New York, is declared broken as a result of British land swindles.

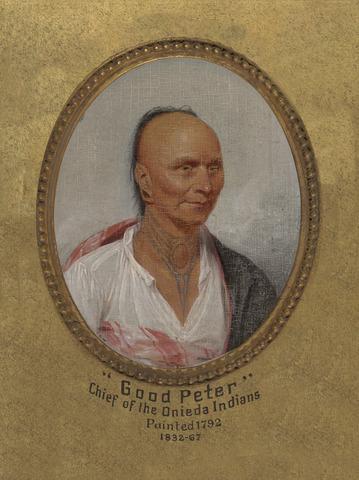

- 1754: Peter Agwrongdougwas, "Good Peter," an Oneida, has begun evangelizing.

- 1754: French and Indian War (to 1763).

- 1754: Eleazar Wheelock, a Congregationalist, begins a school at Lebanon, Connecticut, to train Native catechists.

- 1755: At a Grand Council at Mount Johnson, the Iroquois Covenant Chain is renewed and restored.

- 1755: The Great Expulsion of Acadians (pictured right).

- 1756: William Johnson is appointed the English superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies.

- 1759: Molly Brant, a Mohawk, moves in with William Johnson. They will have a number of children: perhaps eight; reports differ.

- 1759: Fort Niagara falls to a British force led by William Johnson; Quebec is captured by the British.

- 1760: New France capitulates. Johnson negotiates a treaty between the British and the "Seven Fires," by which the latter enter into the Covenant Chain as neutrals.

- 1761: Neolin, a Lenape (Delaware) prophet, receives a vision with Christian overtones from the Master of Life. He preaches resistance to Europeans and the reform of Indigenous ways.

- 1763: The Treaty of Paris gives Britain colonial authority over Canada. Britain ignores a promise to Indigenous peoples to evacuate the Ohio Valley.

- 1763: The King issues a Royal Proclamation, guaranteeing Aboriginal land rights in a vast territory described in terms suggesting everything west of the Appalachians and south of the Ohio.

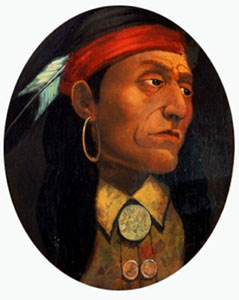

- 1763: Pontiac, using Neolin's teachings, calls a council to lay siege to Fort Detroit. This initiates a rebellion known as Pontiac's War, an effort to defend Indigenous lands from British and American invasion.

- 1764: The Treaty of Niagara is agreed between Britain and First Nations.

- 1764: The Seneca and the British conclude the first land surrender under the terms of the Royal Proclamation.

- 1766: At Fort Ontario (at present-day Oswego, NY), Pontiac and William Johnson make a peace agreement.

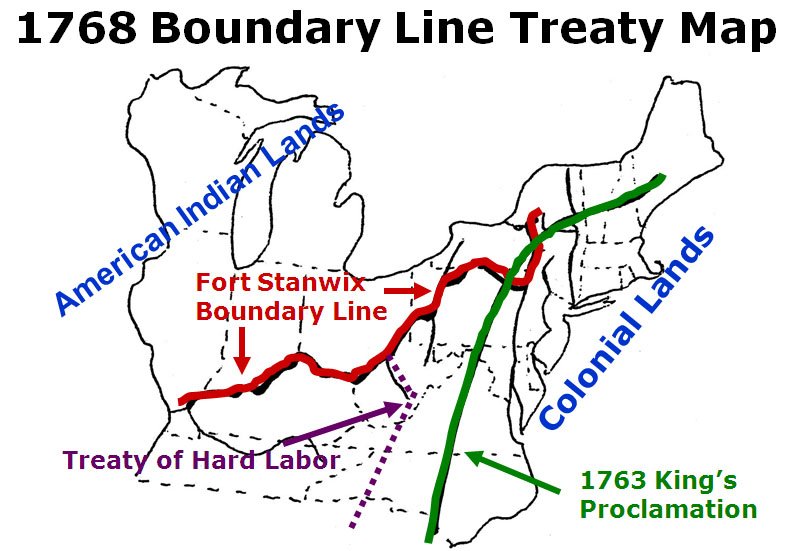

- 1768: The Treaty of Fort Stanwix aims to clarify and partly re-define the boundary established in the Royal Proclamation beyond which Aboriginal land rights are protected.

- 1771: Charles Inglis of Trinity Church, New York, writes the colonial secretary in England to recommend a missionary policy closer to that of the French Jesuits.

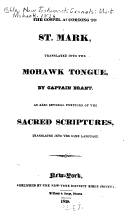

- 1772: Joseph Brant, a Mohawk leader, Molly's brother, goes to live with John Stuart, an Anglican missionary. They will collaborate on translations of the gospel of Mark and the church catechism.

- 1774: Lord Dunmore of Virginia leads a war against Indigenous peoples who are defending their homelands in the Ohio River valley. One result is to move many Indigenous peoples to support Britain during the American Revolution.

- 1775: The American Revolution begins.

- 1776: The Declaration of Independence lists the American colonists' grievances against England. Among other things, it says that the king "has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions." (Nothing is said of the "known rule of warfare" of the squatters in First Nations territories.)

- 1777: Hokoleskwa, Chief Cornstalk of the Shawnee, is murdered by soldiers at Fort Randoph on a diplomatic mission (pictured at right). The Shawnee, formerly neutral, begin moving to support Britain.

- 1783: The Treaty of Paris ends the Revolutionary War. Despite Britain's earlier promises, the Treaty fails to secure recognition of Indigenous lands. Most Haudenosaunee leave, are forced out of, or, in the end, are expelled from New York. Most emigrate to Canada; some move to the New York side of Niagara.

- 1783: The Crawford Purchases transfer to the Crown Anishnaabe lands along the north shore of Lake Ontario and the western St. Lawrence River, so that they can be granted to loyalist settlers.

- 1784: Montreal entrepreneurs create the North West Company, which comes to dominate the fur trade in Canada, outstripping the Hudson's Bay Company by about 10 to 1.

- 1784: In a treaty signed at Fort Stanwix, Haudenosaunee representatives cede huge amounts of land to the United States. The treaty will be repudiated by most Indigenous nations.

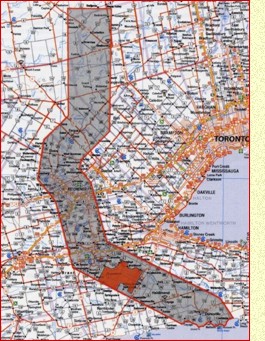

- 1784: In the Haldimand Proclamation the governor-general of Canada grants a large tract of land along the Grand River (purchased from the Mississaugas) to the Haudenosaunee. Today, only 5% to 10% of the original land grant is still recognized by settler governments as belonging to the Six Nations, but much of the land is in dispute.

- 1785: The Northwest Indian War begins (to 1795).

- 1786: Joseph Brant and the Haudenosaunee light a council fire at Brownstown (near Detroit), and gather an Indigenous confederacy to fight for common Indigenous land ownership in the lands protected by the Royal Proclamation.

- 1787: Congress passes the Northwest Ordinance, claiming jurisdiction over Indigenous and settler peoples in lands also claimed by Britain and Brant's Confederacy.

- 1795: The Jay Treaty defines the international boundary around the western Great Lakes. Indigenous voices are absent from the negotiations. Britain gives up its forts in the pays d'en haut leaving Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples defenceless against American armies and settlers. Indigenous peoples are guaranteed the right to cross the border at will.

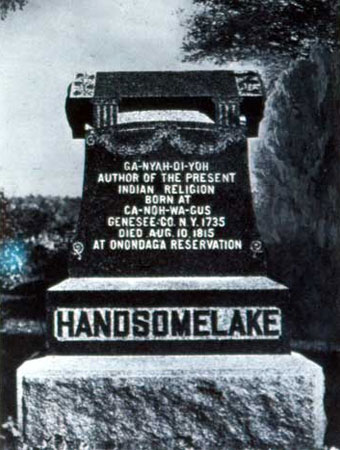

- 1799: Handsome Lake, a Seneca, has a series of visions that empower him to become a major prophet. His teaching connects traditional and Christian wisdom.

- 1808: The brothers Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh establish Prophetstown in Indiana territory, founded on a spirituality with textures of Catholicism and Shakerism. It becomes the largest First Nations community in Ohio country. It promotes a pan-Indian resistance to assimilation into settler culture.

- 1812: The War of 1812 begins. Tecumseh is appointed a British brigadier general in charge of Indigenous soldiers against the Americans.

- 1815: The Treaty of Ghent is approved, ending the war.

Archival sources are spread far and wide, but a large proportion of primary source material has been transcribed and published, and, of that, a significant proportion is now available on-line. For serious research that's intended for publication, archival sources should be consulted, since errors do creep into transcriptions. But for general purposes transcriptions and dependable Internet sources are a very welcome resource.

- Library and Archives Canada. This institution isn't particularly easy to use. For most purposes you have to go to Ottawa in person, although if you know precisely what you want, you can order up a copy. For many documents you have to wait months for Protection of Privacy clearance. If you diligently search the LAC website (it's

not user-friendly), you can unearth helfpul overviews, finding aids, and summaries. The good news is that LAC has scanned a large number of documents for on-line use, and also that staff will respond helpfully to email enquiries. Some of LAC's overall descriptions for this period are the following:

not user-friendly), you can unearth helfpul overviews, finding aids, and summaries. The good news is that LAC has scanned a large number of documents for on-line use, and also that staff will respond helpfully to email enquiries. Some of LAC's overall descriptions for this period are the following:

- Published government documents, colonial period. For several jurisdictions some very hard-working scholars in past generations transcribed great quantities of very interesting documents and published them. Only a few years ago (I remember the days!) you'd only find these in a good research library, and then you could only use them on-site during business hours, but many of these are now available on-line.

- For Canada, Adam Shortt and Arthur G. Doughty, Documents relating to the constitutional history of Canada 1759–1791, part 1 published in 1914, and part 2 published in 1918

- Also for Canada, W.P.M. Kennedy, Statutes, Treaties, and Documents of the Canadian Constitution 1713–1929, Oxford, 1930, linked here

- Also for Canada, New France Archives

- Québec makes available Documents historiques for New France in 4 vols., 1883–1885, volume 1 here

- For New York, including material on the Six Nations, Documentary History of the State of New York (under the direction of Christopher Morgan, Secretary of State), 4 volumes, Albany, 1849–1851. Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4

- Also for New York, Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York,..., 15 vols., Albany, 1853–1887, available on-line at Haithi Trust

- Also for New York, a list, with links, of other Native American materials

- The New York State Library has a full description of dozens of other on-lne historical documents, linked here

- The papers of William Johnson, British superintendent of Indian affairs, northern American colonies, 1756–1774

- Church documents

- The Vatican's documents relating to Roman Catholicism in Canada, 1622–1799, are listed in a guide in English (pdf)

- Records relating to Canada from the archives of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel beginning in 1722 are at British On-line Archives. However, this isn't free. Many academic institutions pay for access for their faculty and students. Many more have the microfilms. The 1000-page classified digest of SPG records is at Canadiana Online.

- Non-institutional documents

- James Dow McCallum, The Letters of Eleazar Wheelock's Indians, Dartmouth College, 1932

- Samuel Kirkland, The Journals of Samuel Kirkland: 18th-century Missionary to the Iroquois, Government Agent, Father of Hamilton College, ed. Walter Pilkington (Clinton, NY: Hamilton College, 1980)

- Joseph Johnson, To Do Good To My Indian Brethren: The Writings of Joseph Johnson, 1751–1776, ed. Laura J. Murray (Amherst: U of Massachusetts Press, 1998)

- Samson Occom, The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan: Leadership and Literature in Eighteenth-Century Native America, ed. Joanna Brooks (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006)

- John Norton, Mohawk Memoir from the War of 1812: John Norton - Teyoninhokarawen, ed. Carl Benn (U of Toronto Press, 2019)

John Norton, The Journal of Major John Norton, 1809-1816, ed. James J. Talman and Carl F. Klinck (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1970)

John Norton, The Journal of Major John Norton, 1809-1816, ed. James J. Talman and Carl F. Klinck (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1970)- John Norton, Mohawk Memoir from the War of 1812: John Norton - Teyoninhokarawen, ed. Carl Benn (U of Toronto Press, 2019). (This duplicates material in the previously listed work, but adds considerable historical commentary.)

- David Zeisberger, David Zeisberger's Official Diary, Fairfield, 1791-1795, ed. Paul Eugene Mueller, in Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society 19 (1963), 5–229

- Charles Johnson, ed., Valley of the Six Nations: A Collection of Documents (Champlain Society, 2013)

- [Black Hawk and William Apess,] Native Memoirs from the War of 1812, ed. Carl Benn (Johns Hopkins, 2013)

- Other guides

- Brandon University, research guide to Canadian history

- University of Toronto, general Canadian history, open access

Protestants begin thinking about mission. Roman Catholic foreign missionaries were energetically at work from the earliest days of New Spain, frequently mitigating the brutality of the explorers, traders, and settlers. Protestant settlers were far more fitful in their attempts to "convert the heathen," even though the latter was typically a mandate in their charters for colonization. The more zealouso American Protestants were jealous of the successful example of the French. Thus a missionary in the 1750s (John Ogilvie) wrote the following to the SPG:

There is not a Nation bordering upon the five great lakes, or the banks of the Ohio, the Mississippi, all the way to Louisiana, but what are supplied with priests & schoolmastres, & have very decent places of worship, with every splendid utensil of their religion. How ought we to blush at our coldness & shameful indiffernece to the propagation of our most excellent religion.

In this section we turn our attention to the Indigenous peoples that wound up in Canada, who were within the reach of the settler Protestants in New York and New England: the Haudenosaunee west of Albany. We've seen that a handful of Dutch Reformed clergy in New York did connect with them in the period of New Netherland (before 1667), but that Roman Catholics had made by far the stronger impression.

The challenge to English Protestants to step up their game would become more acute in Canada in 1763 when colonial authority over the territory passed from France to England. In addition to evangelistic motives, the Church of England, as the established church in England, also evidenced a political agenda: it was sure that making people Anglican would make them more loyal to the King, and to settler political interests.

The Mohawks and the Anglicans

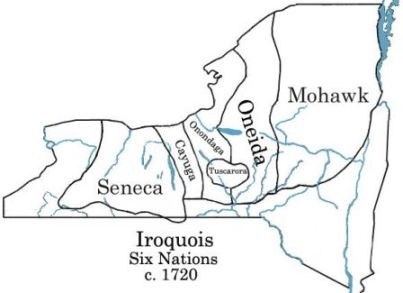

Geographical context. It will be recalled that, before the American Revolution, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy occupied a 300-kilometre corridor from near Albany to Niagara Falls, like a huge Longhouse; and that the Mohawks were the Eastern Door of the Longhouse. They therefore had the closest relations with settlers (first Dutch, then English) in Albany, and, accordingly, they attracted the most missionary attention. It will also be recalled that, from the 1670s, most Roman Catholic converts among the Mohawks had moved north to Jesuit missions or réductions in the St. Lawrence River Valley and had become autochtones domiciliés, sedentary First Peoples, in the federation called the Seven Fires. The council fire for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, where decisions were made for all the Five (later Six) Nations, was in Onondaga territory, near present-day Syracuse. The population of this territory in 1770 was about 8000 Haudenosaunee, plus another 800 from other Indigenous and settler nations.

Geographical context. It will be recalled that, before the American Revolution, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy occupied a 300-kilometre corridor from near Albany to Niagara Falls, like a huge Longhouse; and that the Mohawks were the Eastern Door of the Longhouse. They therefore had the closest relations with settlers (first Dutch, then English) in Albany, and, accordingly, they attracted the most missionary attention. It will also be recalled that, from the 1670s, most Roman Catholic converts among the Mohawks had moved north to Jesuit missions or réductions in the St. Lawrence River Valley and had become autochtones domiciliés, sedentary First Peoples, in the federation called the Seven Fires. The council fire for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, where decisions were made for all the Five (later Six) Nations, was in Onondaga territory, near present-day Syracuse. The population of this territory in 1770 was about 8000 Haudenosaunee, plus another 800 from other Indigenous and settler nations.

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts ("SPG").This Church of England missionary society was founded in 1701 to spread the gospel and support English colonists in "the king’s “plantations, colonies, and factories beyond the seas.” Before the American Revolution, its work with the Mohawks was the most persistent of all its Native North American missions. By 1715 it had translated enough of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer to support services of worship. The SPG was highly clerica listic and Eurocentric, which limited its success for its first three or four decades in Iroquoia, especially since its mission there was really only adjunct to settler ministry in Albany. Still, we read that in the early decades of the SPG mission Mohawk women were independently taking the initiative to lead prayer groups and to teach some Christian principles.

listic and Eurocentric, which limited its success for its first three or four decades in Iroquoia, especially since its mission there was really only adjunct to settler ministry in Albany. Still, we read that in the early decades of the SPG mission Mohawk women were independently taking the initiative to lead prayer groups and to teach some Christian principles.

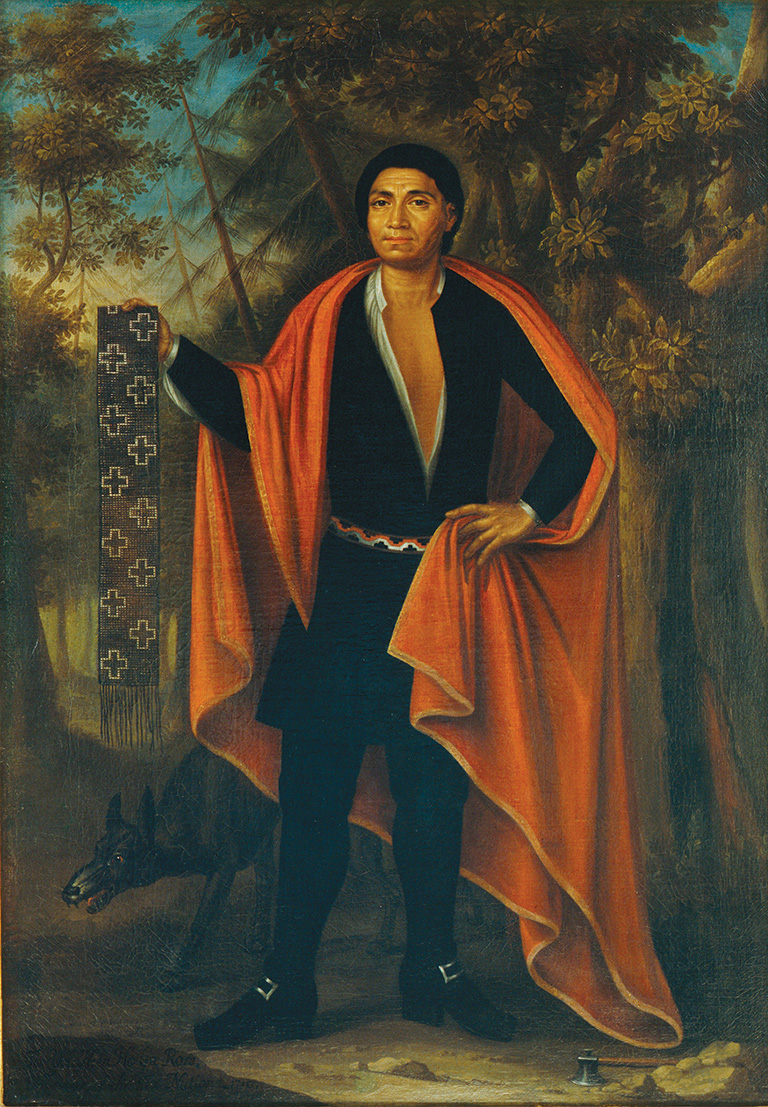

The four "Indian Kings." In 1710, during "Queen Anne's War," as a tactic for strengthening an alliance between the English and the Haudneosaunee, four "Indian kings" were taken to England to thrill Londoners, appear before the SPG, and meet the Queen. Of course the First Nations didn't actually have kings; three Mohawks and one Mahican played the part. It was a serious exercise in diplomacy mixed with a public relations stunt. It made an impression. The Dutch artist Jan Verelst painted a portrait of each of the "kings" (see one of them at theleft). The Queen became fully inspired to support the mission to the Mohawks. She provided a church, a missionary house, a fort ("Fort Hunter"), prayer books, bibles, decorations, and a full silver communion set (pictured below right). (The communion set, now divided between Grand River and Tyendinaga, has an interesting later history of its own; see the article in the linked pdf.)

Mohawk Christian leaders. Building up a Mohawk Anglican church required the leadership of native catechists, schoolmasters, and liturgical leaders.

- The "Indian king" pictured above was Tejonihokarawa, called Hendrick by the English. After he returned to the Mohawk River valley he became a lay preacher and assistant to the SPG missionary. Within six months the t

eam oversaw a hundred baptisms of Mohawk Christians. The reports are than by 1740 most Mohawks were baptized. The historian Edward E. Andrews notes that Hendricks was "a Mahican Mohawk who signed his name in French, allied himself with the Dutch Reformed Church, and begged for English missionaries,... a product of the interlocking cultural matrices ... in the Iroquoian borderlands." Later Chief Hendrick became one of the best known and influential Mohawk leaders.

eam oversaw a hundred baptisms of Mohawk Christians. The reports are than by 1740 most Mohawks were baptized. The historian Edward E. Andrews notes that Hendricks was "a Mahican Mohawk who signed his name in French, allied himself with the Dutch Reformed Church, and begged for English missionaries,... a product of the interlocking cultural matrices ... in the Iroquoian borderlands." Later Chief Hendrick became one of the best known and influential Mohawk leaders. - In the early 1740s Mohawk Christian leaders with the Englisih names Daniel and Cornelius were exercising spiritual authority for the Anglicans.

- In the 1750s an elder named Abraham was an influential lay leader. A prominent Presbyterian minister in Connecticut (Jonathan Edwards) called Abraham "a man of great solidity, prudence, devotion, and strict conversation.”

- Abraham's son Sahonwadie, whom the English called Paulus, was an Anglican lay reader and spiritual leader. He continued in that position into the years when the New York Mohawks had moved to Upper Canada.

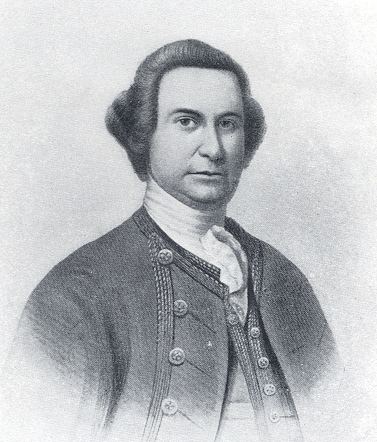

Sir William Johnson (1715?–1774). Johnson (pictured below right) was Britain's superintendent of Indian affairs for the northern American colonies from 1756 to his death. He had been living in the Mohawk River valley since 1738, first as an agent for a wealthy uncle but increasingly on his own as a trader, public official, and military commander. He became fully at home with the Mohawk language and culture; Chief Hendrick became one of his mentors in that process. He married (à la façon du pays) Gonwatsijayenni, Molly (Mary) Brant, and had a number of children with her. (He actually had dozens of children with an indeterminate number of women, mainly Mohawk.) He worked hard to protect the Haudenosaunee from settlers' designs on their land and assaults on their culture. But he also maintained his British lifestyle in an elegant home (pictured below) which is now op en to the public in a state park. He supported his lifestyle with black slaves and white indentured servants. He was generally trusted (but also at least slightly mistrusted) by both the Haudenosaunee and the British: he was a master negotiator, or as some say a bit of a con man. While protecting Indigenous lands from settlement, he also was able to acquire a considerable amount of property, making him, by some accounts, the second largest property-owner in British America. He was a committed Anglican, and apparently a sincerely devout one.

en to the public in a state park. He supported his lifestyle with black slaves and white indentured servants. He was generally trusted (but also at least slightly mistrusted) by both the Haudenosaunee and the British: he was a master negotiator, or as some say a bit of a con man. While protecting Indigenous lands from settlement, he also was able to acquire a considerable amount of property, making him, by some accounts, the second largest property-owner in British America. He was a committed Anglican, and apparently a sincerely devout one.

(The late Norm Casey, the long-time Anglican pastor of Six Nations, used to lead his congregations and friends in occasional historical tours to the Mohawk Valley, including Johnson Hall [pictured below left]. He would note that Johnson's home was the model for the home in which the Mohawk poet and performer Pauline Johnson was raised on the Grand River.) .

Johnson's missionary strategy. With the outbreak of the French and Indian War in 1754, and for another fifteen years, the SPG's attention in Iroquoia languished. This state of affairs disappointed Johnson. He worked with the clergy at the influential Trinity Church, New York, to develop a visionary plan for mission work in the Valley. He invited the clergy up to his estate to meet Mohawk leaders and exchange wampum belts, and he guided their thinking about mission strategy in another direction from the SPG's conventional "old, beaten" way, which prioritized clergy authority, a centralized location, and Indigenous assimilation into English society. Instead, Johnson was positively impressed by the more inculturating approach of the Jesuits, which had obviously been highly successful. The outcome was a lengthy memorandum in 1771 from Charles Inglis of Trinity Church to the colonial secretary, Lord Hillsborough. Its principles were evidently Johnson's. They include the following:

- Conversion should precede Europeanization, since "manners are the result of principles." (In any event, the Mohawks are already "in some measure Civilised," since they cultivate land, have tradespeople, raise cattle, are professors of Christianity, and "are as regular and virtuous in their conduct as the majority of white people.")

- Settler officials should "avoid whatever might give offence to the Indians," to avoid the self-defeating mistakes of excessively Eurocentric approaches.

- SPG instructions to the missionaries should first be vetted by William Johnson.

- Missionaries should identify those features of Haudenosaunee piety that can be affirmed. As a parallel, Inglis says that the first preachers of Christianity exploited resemblances between the Christian message and the Eleusianian mysteries.

- Missionaries should live among the Haudenosaunee, not itinerate from Albany, or recruit Indigenous children into schools in settler communities.

I've identified what I think are some highlights in this document, but, to be honest, there are also some "lowlights." The document is indeed quite Eurocentric, though that's no doubt partly with a view to its aristocratic English readers. It's also highly anti-Catholic prejudice, and generally governed by considerations of political expediency.

Moor's Charity School, 1754

Eleazar Wheelock. Wheelock was a Congregationalist pastor in Lebanon, Connecticut, and an itinerant revivalist preacher during the "First Great Awakening" of the 1730s and 1740s. Opponents of the Great Awakening punished the revivalist preachers by taking away their salary in 1743, and so Wheelock made up some income by taking in students. One of them, though, wasn't a paying customer, but a charity case. That was a Mohegan student named Samson Occom (pictured here), who  became a Christian and a celebrated (though poor) preacher. Flushed with this success, Wheelock decided in 1754 to set up an Indian residential school for Indigenous boys and girls. The school was named after a wealthy Connecticut farmer who sponsored the school financially. Wheelock combined a profound disdain for Indigenous peoples, an autocratic nature, a penchant for self-advertisement, a narrow understanding of Christianity, and Eurocentric goals for education. He was also hard to please. He persevered for fifteen years before he gave up and opened a new school primarily for settler students. That was the origin of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, now one of the eight "Ivy League" colleges.

became a Christian and a celebrated (though poor) preacher. Flushed with this success, Wheelock decided in 1754 to set up an Indian residential school for Indigenous boys and girls. The school was named after a wealthy Connecticut farmer who sponsored the school financially. Wheelock combined a profound disdain for Indigenous peoples, an autocratic nature, a penchant for self-advertisement, a narrow understanding of Christianity, and Eurocentric goals for education. He was also hard to please. He persevered for fifteen years before he gave up and opened a new school primarily for settler students. That was the origin of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, now one of the eight "Ivy League" colleges.

Purpose of the school. Wheelock proposed to "purge all the Indian out" of his pupils, convert them (if they weren't already Christian), and train them to be missionaries to Indigenous peoples (not necessarily their own peoples; just any Indigenous peoples). Instruction included Latin and Greek, and classical western literature. The school prefigured the later Indian residential schools of Canada in many ways:

- It took children away from their families;

- it aggressively acculturated the children into English manners;

- it indoctrinated them with a particular form of Christianity (in Wheelock's case, "New Light" Calvinism);

- it made them do farm work under the guise of agricultural training;

- it disdained their culture;

- it punished them harshly.

Wheelock arranged for missionary appointments in Iroquoia for some of the graduates. He sought to oversee them in their mission appointments, but, being ignorant of Haudenosaunee ways, oblivious to the needs of the missionaries, and thiristy for appreciation, he very often alienated them.

The record of the school. During the first seven years Iroquoia was a war zone and Wheelock received no students from that region. Instead he taught Indigenous pupils from the northeastern American colonies such as Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey. With the peace of the Iroquois Covenant Chain in 1760, Wheelock began recruiting Haudenosaunee students as well. By one count, during its whole existence the school taught a total of 52 Indigenous pupils. Several left prematurely; a few died. Five became missionaries, and seven became schoolmasters. Few if any of its pupils lived up to Wheelock's desire to produce people like himself.

Fund-raising. Wheelock marketed the school aggressively, writing public relations materials and collaring potential benefactors. Since running the school was his business, he p rofited from some of the proceeds. In 1766 he acted on a particularly inspired fund-raising idea: he'd send an Indigenous minister to impress wealthy folks in England. His choice, of course, was Samson Occom, who had made good as an ordained minister and an effective peracher. Occom, along with a settler colleague, returned with the remarkable sum of £12,000. As a very rough estimate, that might be worth Cdn $3,500,000 today. But by 1770 Wheelock was discouraged by the failures of the school, which he attributed to the inferior nature of Indigenous peoples. In addition, his hopes of branching out into Indigenous lands were opposed by Wliliam Johnson, who resisted colonial settlement and also didn't much like Wheelock. Wheelock therefore essentially absconded with the funds that Occom had raised for Indigenous schooling, moved to New Hampshire, and used the money for settler education. Occom said, "All the money has done is, it has made Doctor's family very grand in the world."

rofited from some of the proceeds. In 1766 he acted on a particularly inspired fund-raising idea: he'd send an Indigenous minister to impress wealthy folks in England. His choice, of course, was Samson Occom, who had made good as an ordained minister and an effective peracher. Occom, along with a settler colleague, returned with the remarkable sum of £12,000. As a very rough estimate, that might be worth Cdn $3,500,000 today. But by 1770 Wheelock was discouraged by the failures of the school, which he attributed to the inferior nature of Indigenous peoples. In addition, his hopes of branching out into Indigenous lands were opposed by Wliliam Johnson, who resisted colonial settlement and also didn't much like Wheelock. Wheelock therefore essentially absconded with the funds that Occom had raised for Indigenous schooling, moved to New Hampshire, and used the money for settler education. Occom said, "All the money has done is, it has made Doctor's family very grand in the world."

Criticisms. Both settler and Indigenous people grew very critical of Wheelock's school.

- William Johnson at first gave the school some support, but soon came to oppose it.

- As superintendent of Indian affairs, with the task of building trust between the Six Nations and Britain, he knew that any settler efforts to change Indigenous ways of life rightly triggered suspicions.

- He didn't like the idea of raising Indigenous children in ssettler communities.

- He didn't like the idea of "civilizing" Indigenous people since he didn't think that settler people were exactly models of humanity.

- He disliked the revivalist and legalistic style of Wheelock's Christianity. He disliked its "air of the most Enthusiastical Cant" and its “Belchings of the Spirit.” He thought that Wheelock made his pupils "gloomy."

- He was suspicious of Wheelock 's financial ambitions, and especially his possible designs on First Nations lands, which could jeopardize the peace.

- As a high-church Anglican, whose church was "established" in England under the King as supreme governor, Johnson was antagonistic towards "dissenters" (the Anglican term for non-Anglican Protestants), who sometimes supported civil rebellion.

- The Onondaga Council began to hear about Wheelock's rigid Eurocentric approach and his resort to corporal punishment. When Wheelock asked the Council to send him more children, the members replied: "Brother, you must learn of the French ministers if you would understand, & know how to treat Indians."

Some pupils. Several significant Christian leaders attended Wheelock's school.

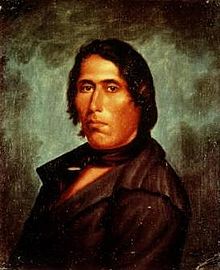

- Joseph Brant (Thayandanegea), 1743–1807, pictured right, was the one who would become most celebrated.

- Samuel Kirkland was a settler child who attended the school, and went on to the College of New Jersey. He launched a mission to the Seneca that failed pretty miserably, and then moved on to the Oneida, among whom he was arguably successful, though divisive, missionary to the Oneida. He broke with Wheelock.

- Joseph Woolley, a member of the Lenape (Delaware) nation, was a missionary to the Oneida, despite the differences in their language and culture.

- David Fowler, a Montauk, whose sister married Samson Occum; he was sent among the Oneida.

Hannah Garrett, a Pequot, who married Fowler and worked with him among the Oneida.

Hannah Garrett, a Pequot, who married Fowler and worked with him among the Oneida. - Hezekiah Calvin, a Lenape, taught among the Mohawk at Fort Hunter.

- Samuel Ashpo, a Mohegan, who worked briefly among the Oneida.

- Joseph Johnson, a Mohegan, who worked for a while among the Oneida; he was Samson Occom's son-in-law.

- Mundius, an Oneida, who returned to teach among the Oneida.

- Five Mohawk assistants (called "ushers"): Moses and Johannes (both recruited by Joseph Brant), "great" Abraham, "little" Abraham, and Peter.

Older histories usually single out Kirkland as Wheelock's most successful missionary graduate, but that may be because (1) he wrote more than the others, (2) he inflated himself more than the others, and (3) he was a settler. Those who have looked closely at the documentation have come away with the sense that Kirkland's First Nations colleagues and mentors helped him out of scrapes, challenged his bad ideas, and generally made him look good.

The Oneida

A case study. Before the American Revolution, Christianities emerged and gained substantial followings in all the Six Nations, except possibly the Cayuga. Although the Mohawk at first attracted the most attention from settler Protestants (largely because it was closest to Albany), the Oneida nation soon appeared to be a comparably promising prospect for Christian mission. Indeed, its language and culture were more similar to the Mohawks than to the other four of the Six Nations, and the kinship ties of the Mohawk and Oneida were close. Over all, the Oneida situation probably best evidences the complex interplays of social, cultural, political, and theological differences and tensions in Indigenous–settler Christianities, and so it makes for a particularly fascinating study. Although this specific case is connected to a specific time, place, and set of people, it's in many ways representative of patterns of complexity in settler and Indigenous Christianities throughout Canadian history.

Geography. The Oneida were the second fire of the Longhouse, just beyond the Mohawks from the Dutch and English settlements around Albany. They were the smallest in population of the Five (later Six) Nations. Their territory extended over six million acres in what's now central New York, where a city, county, and lake bear the Oneida name today. Oneida territory was culturally diverse in the eighteenth century, as it became a destination for Indigenous immigrants and refugees from elsewhere. Among these the Tuscarora people were most notable; after they were forced out of North Carolina by settler territorial encroachment and war, they came to the Oneida region after 1712 and were accepted as the sixth of the Six Nations in 1722. But Lenape, Shawnee, and Mahicans were there too, as well as other Six Nations peoples, as well as British, Dutch, and German settler people. The Oneida were particularly closely connected to the Mohawks, whose language and culture were more similar than the other four of the Six Nations, and who shared many kinship lines. The main settlements in Oneida territory were:

- Old Oneida, the capital in the late seventeenth century. It was located on a hill in what's now southeast Oneida, NY.

- Kanonwalohale, a fortified village with a moat at what's now Oneida Castle, NY, which was developed a few years later. Like Old Oneida, it stood in a defensive location because of a history of attacks from Canada. Kanonwalohale became the new capital as an outcome of community political strains.

- Onaquaga, near what's now Windsor, in southern New York state, on the Susquehanna River. It became a substantial trading post in the 1740s. It grew at the expense of the first two. It became a cosmopolitan town.

Social divisions. Tensions existed between the Oneida of traditional ways and the Oneida who were open to British ways.

- Kanonwalohale and Onaquaga seemed more British. Many residents farmed and raised animals, adopted English material culture (such as clothing, mirrors, and dining implements), and lived as nuclear families in houses and cabins instead of in longhouses. These things weren't true at Old Oneida.

- Old Oneida was the centre of authority for hereditary sachems (hodiyahnehsonh, peace chiefs) and women elders. Kanonwalohale and Onaquaga had a larger presence of Oneida hunter/warriors, who had fought side by side with British soldiers, were more comfortable with British ways, and were more open to the benefits of connecting with British officials and traders. The sachems and women elders certainly had historic reasons to mistrust the settlers and white travelers across their territory who encroached on their land, brought disease, hunted their game, and fished their lakes.

Reasons for Protestant engagement. Many Anglican, Presbyterian, and Congregationalist evangelists, both settler and Indigenous, found a ready hearing from the Oneida, especially those at Kanonwalohale and Onaquaga, who offered warm hospitality to them, or at least to the more likable ones. . Among the reasons that historians suggest to explain why many Oneida were open to Christian ideas are the following:

- The missionaries might help them in worldly and material ways, such as arranging food, bringing gifts, making trade connections, teaching skills in agriculture and husbandry, and healing.

- They could be intermediaries to English power and protection.

- There were many stories of how Christian neophytes were able to solve their problems with alcohol, or effectively address other personal problems.

- Christianity offered spiritual power and divine wisdom, maybe not greater than what was available in traditional religion, but at least worth exploring.

- Christian schoolmasters taught literacy and other knowledge that could help people defend themselves against, maybe even make use of, the systems of settler colonialism.

As the historian Alan Taylor has said, the Oneida were not "passive recipients" but "demanding catalysts" for Protestant missionary work.

Leaders. The most effective Christian leaders among the Oneida were, not surprisingly, the Oneida themselves, not settlers, and not members of other First Nations. Thus although several Algonquian speaking First Nations missionaries made valiant efforts with the Oneida, they usually flamed out. And the achievements of the settler missionaries were usually mixed.

- The young missionary David Brainerd may have served briefly at Onaquaga in 1745. A biography of Brainerd by the Connecticut theologian Jonathan Edwards (available here as a pdf) made him one of the most widely known ministers in colonial America. But he was more successful elsewhere.

- Elihu Spencer, a Presbyterian minister, served at Onaquaga in 1748–1749. He had a son, Thomas Spencer, by an unnamed First Nations woman, whom he abandoned. His "New Light" revivalist preaching is said to have influenced "Good Peter" (below).

- Rebecca Kellogg Ashley was taken captive as a little girl in Deerfield, Massachusetts, and adopted by Mohawks. She returned to settler society as an adult but continued to identify as a Mohawk. She was the translator for Elihu Spencer, Gideon Hawley (who called her "extraordinary"), and other settler preachers at the Six Nations. Thus when the clergy were preaching and teaching, it was actually Rebecca who was being heard. She died in 1757 at Onaquaga.

- Peter Agwrongdougwa, "Good Peter," of Onaquaga (picture

d right), a sachem of the Eel clan, warrior, orator, Christian elder, and advocate for Indigenous land rights, accepted the Christian faith in (perhaps) the 1740s. He learned to read the Mohawk Bible, exercised a ministry of itinerant evangelism across Iroquoia, and led public worship. He's also known for his neck tattoo.

d right), a sachem of the Eel clan, warrior, orator, Christian elder, and advocate for Indigenous land rights, accepted the Christian faith in (perhaps) the 1740s. He learned to read the Mohawk Bible, exercised a ministry of itinerant evangelism across Iroquoia, and led public worship. He's also known for his neck tattoo. - Gideon Hawley, a Congregationalist minister, preached actively at Onaquaga from 1754 until he was forced out by the French and Indian War in 1756.

- Isaac Dakayenensere was a Christian leader with "Good Peter" at Onaquaga. He learned to read and write, and preached widely. In 1765 his daughter married Joseph Brant, who owned property at Onaquaga. The daughter died of tuberculosis in 1771.

- "Deacon Thomas" was another "New Light" convert who worked with Isaac and "Good Peter" at Onaquaga, and was also known for his passionate 90-minute sermons at Kanonwalohale. He was shot and killed by the British as an American spy at Kahnawake in 1779.

- Samson Occom made preaching visits to Oneida territory from 1761 to 1763, and won the respect of the elders. (An excerpt from his short autobiography is available here.)

- Joseph Woolley, David Fowler, Hannah Garrett, Samuel Ashpo, and Joseph Johnson, named above as missionaries or schoolmasters trained by Wheelock, also worked in Oneida country. All were Algonquian speakers. Wheelock apparently thought that all Indigenous people would immediately win a warm reception with all other Indigenous people, which was a little like thinking that people from Poland would find all doors swinging open to them in Scotland. But the Algonquian-speaking missionaries found the Oneida language forbiddingly difficult, and its culture foreign. Besides, they had their own personal problems, such as Fowler with his temper, and Ashpo with alcohol and sex. Most of them were discouraged to see so few results from their teaching, as when the pupils at their schools left for weeks on end during the seasonal hunt, Except for Woolley, who died of tuberculosis at Onaquaga, they all returned home within two or three years.

- Samuel Kirkland (1741–1808), the settler Presbyterian minister and a Moor's graduate, was an active missionary among the Oneida until the Revolutionary War, when he became an army chaplain for the Patriots. During the war he wa an antagonist of Joseph Brant, who was a Loyalist, but after the war they maintained an affectionate correspondence. Ostensibly a protector of Indigenous lands, he profited handsomely from land speculation in Iroquoia. He repented of this behaviour as his death drew near.

Tensions around Christianities. Christianities unsettled Oneida society, or perhaps more often exacerbated divisions that already existed.

- English missionaries often raised suspicions. Did they have designs on Indigenous land? If they weren't greedy themselves, would their Christianities pave the way for land speculators? The Oneida expressed precisely this anxiety to Wheelock. At the little village of Jeningo, the local Oneida wanted a missionary, but not an English one.

- Haudenosaunee societies were generally on edge during these years of war and settler territorial encroachment, and religious challenges could be particularly disruptive.

- As we noted earlier, traditional elements of Oneida society, typically the hereditary sachems and clan mothers, were naturally anti-English and anti-Christian. They were therefore hostile to Christian preaching and evangelism. In general, the former capital of Old Oneida was hostile to Christianity, while Kanonwalohale embraced it.

- Some parents were ambivalent about literacy and schooling, which usually privileged English ways of knowing, and disparaged First Nations ways. In several cases parents welcomed schooling for their children at first, but cooled later. The missionaries interpreted this pattern as inconstancy.

- Some families divided over religious issues.

Christianities themselves came divided. "New Light" revivalist religion was not like following liturgical texts in the Fort Hunter chapel, and neither was like the Jesuits' processions with sacred objects and Latin chants.

Christianities themselves came divided. "New Light" revivalist religion was not like following liturgical texts in the Fort Hunter chapel, and neither was like the Jesuits' processions with sacred objects and Latin chants. - The "New Light" emphasis on sin and wrath could be profoundly discouraging. Idesa of sin were unfamiliar in traditional Oneida spirituality. Samuel Kirkland told the story in 1767 of being confronted by an intoxicated Oneida in considerable despair who attacked him physically and railed, "I hate you, and all English ministers," and said that he (the Oneida) "was too great a sinner to live;" and said to Kirkland, "You...are the cause of it, by your continual talk of Sin, Sin, Sin, as though there was nothing else in the World.'"

Christianities and Haudenosaunee spirituality. While English missionaries disparaged Oneida culture, and traditional Oneida elders in turn disparaged Christianity, many Oneida Christians saw attractions in both these spiritualities. After all, the Oneida had experienced enough forms of Christianity to know that it was pretty malleable.

- Haudenosaunee tradition and Christianity agreed on a Creator god, and Oneida creation stories bore some similarities to the first chapters of Genesis.

- Sharing, good works, and kindness were intrinsic to both spiritualities.

- Prayers and ceremonies of thanksigiving were common to them as well.

- The dynamic hostility of evil and good were themes in the sacred stories of both traditions.

- The historian Edward E. Andrews suggests that the Oneida could understand Christ, both human and divine, as a kind of shape-shifter, a very familiar being to them.

- Songs and hymns, particularly the Psalms as sung sacred texts, appeared to be very compatible with Oneida cultural and ritual traditions.

- Old Testament stories about the devotion of Isarel to its land, and Biblical language celebrating the landscape and the many strange and beautiful things of creation, struck resonant chords with the Oneida. "O ye mountains and hills, bless ye the Lord!"

- The military imagery of the Old Testament was evocative for the Oneida.

Importance. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 has been called Canada's "magna carrta" of Aboriginal land rights. Its historic authority was recognized by three members of the Supreme Court of Canada in its Calder decision of 1973. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms, section 25, explicitly incorporates the Aboriginal rights recognized by the Royal Proclamation.The Royal  Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1991–1996, highlighted it as a key to Indigenous–settler reconciliation. At first sight it may not appear essential to the story of Indigneous and settler Christianities in Canada. But Indigenous peoples see an intimate connection between land and spirituality that sometimes eludes settler folk; and the councils of the mainline churches in Canada since the 1960s have understood that, as a matter of gospel discipleship, they are called to solidarity with Indigenous peoples in their fight for the recognition of Aboriginal land rights. So the background, intentions, and immediate aftermath of the Royal Proclamation deserve attention.

Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1991–1996, highlighted it as a key to Indigenous–settler reconciliation. At first sight it may not appear essential to the story of Indigneous and settler Christianities in Canada. But Indigenous peoples see an intimate connection between land and spirituality that sometimes eludes settler folk; and the councils of the mainline churches in Canada since the 1960s have understood that, as a matter of gospel discipleship, they are called to solidarity with Indigenous peoples in their fight for the recognition of Aboriginal land rights. So the background, intentions, and immediate aftermath of the Royal Proclamation deserve attention.

Land disputes. Settler encroachments on Indigenous territory and disputes about land generated mayhem, political agitation, violence, and war from the 1740s to the end of the War of 1812. The "Overview" of dates above gives some brief examples. We've just noted some tensions around land use in Haudenosaunee territory before the American Revolution, but those were comparatively benign, since both New York nor Britan wanted to protect their military and trade alliances there, and so avoided provocation as much as possible. The area of dispute most important for Canadian history was the Ohio River valley. This is no longer part of Canada, of course, but until 1795 it was.

Ohio. The Ohio River rises at what's now Pittsburgh, and flows southwest into the Mississippi River at what's now the southern tip of Illinois. This area between the Appalachian mountain range and the Mississippi, south of the Great Lakes, was of critical interest to a number of players. In the years leading up to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the interested parties included the following:

- The various communities that lived there, often in settlements attracting First Nations of different languages and kin connections, along with French traders, missionaries, and explorers, and increasingly with English adventurers.

- The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who claimed the area by right of conquest, and after 1758 included the peoples there in its covenant chain. (An article by Jon William Parmenter discusses this; it's a pdf and may be behind a pay wall.)

- France, which included this area in its map of New France. The relationship of New France to the peoples of the pays d'en haut had long been, for the most part, mutually beneficial, respectful, and peaceful.

- Careless British officials who blurted out that the British should claim sovereignty. Britain officially was much more cautious, at least about land south of the Ohio River. Sir William Johnson, for example, recognized the claims of his friends the Haudenosaunee.

- Colonial leaders in Pennsylvania and Virginia, who wanted to expand their territories.

- Illegal settlers, essentially squatters on Indigenous territory, widely viewed by everyone else as the ne'er-do-well dregs of English society seeking their fortune, at whatever cost to the rest of the world.

There was no peaceful way to keep order in the Ohio. No one had the recognized authority to try. As a result, there were many acts of horrific violence triggering at least equally horrifically violent acts of revenge.

Race. Many historians have traced the racial construction of Indigenous–settler conflict to this period. Colonial settlers were more often lumping all "Indians" together into a single prejudiced stereotype; First Nations peoples began speaking generically of "whites." (True, it's hard to know for sure what the First Nations people were saying, since what they said was almost always written by the settlers, but most historians think that this language of "whites" was accurately represented.) Accordingly, if a settler wanted to avenge a murder by, say, a Shawnee, any "Indian" would do. If a Shawnee wanted to avenge a murder by, say, a Virginian, any "white" would do.

The most dramatic example, shocking in its extreme but otherwise like many others, was the massacre at Gnaddenhutten, Ohio (pictured here). It's now a historical monument. The background to the story begins in the 1740s, wh

en missionaries from the Moravian Church, which taught Christian pacifism, started to sponsor small communities of Lenape (Delaware) Christians. In March 1782 a Pennsylvania militia group raided the Gnaddenhutten community, and finding artifacts like spoons and tea kettles, and noting brands on the horses, decided that they were thieves. As Richard White interpreted it, "for Indian haters," who made stark binary distinctions between "white" and "red," "all these things were marks of whites," and if "Indians" possessed them, they must have stolen them. The militia took the Christian Lenape two or three at a time into slaughterhouses, one for men and the other for women and children, and killed them with mallets and knives — 28 men, 29 women, and 39 women. They plundered the loot, and burned the villages. None of the perpetrators was ever brought to justice.

French and Indian War. This American segment of a global war between European empires, called the Seven Years War, consumed the years from 1754 to 1763. From a First Nations perspective, it was a war to protect Aboriginal lands and rights. Different First Nations allied with different parties, depending on their sense of their strategic interests.

- In general terms, most of the Haudenosaunee remained neutral until 1758, when they partnered with the British.

- The Ojibwe, Odawa, Algonquin, and Wyandot partnered with the French. The Lenape and Shawnee also partnered provisionally with the French, hoping for help in removing their dependence on the Haudenosaunee. The Seneca, at the west end of the Haudenosaunee "longhouse," near French outposts in Niagara, also tilted towards the French.

- The Seven Fires, the "domiciled" Christian peoples of Quebec, supported the French for most of the war, on the condition that they wouldn't be expected to fight the Haudenosaunee. but moved towards neutrality, or even support for the British, under Haudenosaunee influence.

But the victory of either France or Britain wasn't in the interest of any of the First Nations. Their higher strategy was to maintain a balance of power between the two European empires, France and Britain..

Outcome of the war. From the point of view of Euro-Canadian history, the war ended with the fall of Quebec in 1759 and the fall of Montreal in 1760, upon which Britain took authority in Canada pending the Treaty of Paris in 1763. From a First Nations point of view, however, the realy turning-point of the war was the capitulation of the French Fort Niagara (pictured here) in 1759, after British and Haudenosaunee warriors under the command of Sir William Johnson had laid siege. (Seneca warriors who were with the French in the fort exited under a flag of truce, since they didn't want to fight their fellow Haudenosaunee.) You can visit Old Fort Niagara, complete with re-enactors; it's near Youngstown, New York.

Outcome of the war. From the point of view of Euro-Canadian history, the war ended with the fall of Quebec in 1759 and the fall of Montreal in 1760, upon which Britain took authority in Canada pending the Treaty of Paris in 1763. From a First Nations point of view, however, the realy turning-point of the war was the capitulation of the French Fort Niagara (pictured here) in 1759, after British and Haudenosaunee warriors under the command of Sir William Johnson had laid siege. (Seneca warriors who were with the French in the fort exited under a flag of truce, since they didn't want to fight their fellow Haudenosaunee.) You can visit Old Fort Niagara, complete with re-enactors; it's near Youngstown, New York.

With the fall of Fort Niagara, French alliances in the pays d'en haut fell apart, and Indigenous peoples in the Ohio were horrified to realize that the British conqueror would no longer be held in check by France.

The Seneca attempted unsuccessfully to continue the war against Britain with its First Nations allies to the west.

British arrogance. Once Britain won, it made no effort to construct a lasting peace with the First Nations, as New France had done well. To be sure, during the war, Britain ssaid all the right things and made very reassuring promises. In a treaty with 500 chiefs at Easton (in what's now Pennsylvania) in 1758, when Britain needed the support, or at least the neutrality, of First Nations, it promised that, if it won the war, it would leave them at peace in their lands, exit Ohio country, and rebuild a peaceful trading relationship. British officials reiterated this promise in several other situations, as in 1760 at Fort Oswego (now part of Oswego, New York). In the articles of capitulation of Montreal in 1760, Article 40 guaranteed that France's "Indian" allies "shall be maintained in the lands they inhabit," and shall have "liberty of religion." But after the war British leaders, particularly the dreadful Jeffery Amherst, the governor-general of British North America as of 1760, treated Indigenous peoples as conquered subjects. The British:—

- trespassed on and took over Aboriginal lands;

- occupied the former French forts in First Nations territory and erected new ones;

- demanded the unilateral release of prisoners held by Indigenous nations, contrary to time-honoured conventions with the French;

- sent punitive military missions;

- ceased the ceremonies of gift exchanges that had been a fundamental part of the relationship with the French, reflecting the meeting of autonomous parties;

- raised the prices of goods, limited ammunition needed for hunting, and allowed a copious trade in liquor

- ignored and disparaged long-standing diplomatic conventions between European and Aboriginal nations;

- turned a blind eye to settler violence;

- allowed itself to be represented by a number of frankly racist officials.

Amherst expressed the goal, in so many words, of exterminating the Indian race, and wanted to distribute to them blankets infected with smallpox. (If you think that story is a myth, the University of Massacusetts has news for you.) It isn't clear whether he got his way. William Johnson kept advising Amherst to maintain French policies amd the tried-and-true traditions of Indigenous–settler relations, but to no avail.

In early 1763, the news reached Canada that France had ceded its territory to Britain. Indigenous peoples were first crushed, then defiant. They began to prepare for war.

Prophetic movements. During this very troubled period several First Nations and settler prophets, male and female, arose to proclaim messages both spiritual and political that showed the influence of Christianities. While settler churches were generally conservative institutions, the Christian Scriptures are rich with prophecies, apocalyptic visions, condemnations of the rich and powerful, and calls for social justice. They are always a great resource for defiant and radical movements. First Nations prophets often drew on them for messages of reform, renewal, and resistance.

Neolin. One of the most important of these prophets, because of his influence on a First Nations rebellion, was Neolin, a Lenape who was residing in the Ohio country. He received a life-changing vision in 1761 which he described in  language reminiscent of the New Testament book of the Revelation of St. John, but also of First Nations visions and stories. A woman of radiant beauty led him to the summit of a mountain, where a handsome man dressed in white presented him to the Master of Life.

language reminiscent of the New Testament book of the Revelation of St. John, but also of First Nations visions and stories. A woman of radiant beauty led him to the summit of a mountain, where a handsome man dressed in white presented him to the Master of Life.

"I am He who hath created the heavens and the earth," the Master of Life told Neolin. "Because I love you, you must do what I say."

The Master of Life denounced the sins of his children: alcohol, promiscuity, witchcraft, unkindness, and above all their indulgence of settler land-grabbers. Neolin's message combined attacks on settler colonialism, with all its cultural hegemonies and its projects of land dispossession, with calls for the reform of First Nations societies, whose spiritual weakness, he thought, had enabled the settlers. In other words, Neolin saw First Nations peoples not simply as victims of settler colonialism, but as agents who could take control of the situation by deciding to follow God's commandments. And God's principal commandment at this time was to keep First Nations and settler people separate. (Or perhaps it was that Indigenous people should remain separate from the British in particular; there's some doubt.)

Neolin's prophecies appear to connect Christian and First Nations wisdom in the project of social reform and justice. But some elements seem more distinctly Christian than First Nations: direct access to a supreme, all-powerful God who guides history and hands down commandments; the Devil; an afterlife of heaven for the righteous, and hell for the unrepentant; and additional rituals, some of them intended to replace such traditional ceremonies as those involving medicine bags and bundles. Neolin's prophecies are an example of the cultural interchange of Christian and spiritual wisdoms in the project of social justice.

Pontiac's Rebellion. Neolin's prophecies caught on beyond his own Lenape people, and most notably they caught the attention of Obwandiyag (Pontiac), an Odawa war chief in Detroit. That town had a fort, formerly French but now in English hands, and around the fort a diverse population of Odawa, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Wendat peoples. Pontiac succeeded in uniting these peoples in a short-lived, very brutal anti-British action that began with the fort at Detroit. It has been called the First Nations War of Independence. The rebellion moved on to Fort Pitt (at what's now Pittsburgh), Fort Niagara, and the countryside. The rebellion achieve d none of its long-range purposes, but First Nations warriors were effective against British soldiers, and the war was extremely costly to the British in lives and treasury. It was painfully evident to the Lords of the Board of Trade and Plantations in London that a less arrogrant, more conciliatory policy would have been cheaper. Amherst was called home and replaced.

d none of its long-range purposes, but First Nations warriors were effective against British soldiers, and the war was extremely costly to the British in lives and treasury. It was painfully evident to the Lords of the Board of Trade and Plantations in London that a less arrogrant, more conciliatory policy would have been cheaper. Amherst was called home and replaced.

Pontiac continued to seek alliances against the British for another two years. When his taste for war seemed to flag, Charlot Kaské, a Roman Catholic Shawnee war chief, led the resistance in his stead. In 1765 a council of First Nations leaders at Detroit ratified a peace agreement presented by Pontiac and a British emissary.

Drafting the Royal Proclamation. In September 1763, a few months after Britain had received colonial authority over Canada in the Treaty of Paris, one of the King's secretaries of state asked the Commissioners of Trade and Plantations to draft a proclamation "declaratory of the several arrangements to be made in the new acquisitions in America," including matters of "Indian" commerce. The Board evidently kept in mind the dangers of worrying First Nations about the security of their land-holdings. From that point of view they should have announced that Britain had no authority over the land at all. But, on the other hand, their other problem was that settler squatters were invading First Nations lands, and that the colonies, particularly Pennsylvania and Virginia, were eager to expand westward. From that point of view, the Board wanted to assert its authority over the land, so that Britain could flex its muscle to restrain the colonies and expel the squatters. This is the reasonable interpretation offered by the Ojibwe legal scholar John Borrows to explain why the Royal Proclamation, when it was published, looked so double-minded.

Issuing the Royal Proclamation. The Board worked fast, and on October 7, 1763, the king issued his Proclamation. It renamed Canada "the province of Quebec," defined boundaries (or sometimes left them vague), and mandated governments for its new territories. And, most importantly in the long term, it protected Aboriginal lands according to the following provisions:

- The lands of "Indian" nations under the King's protection are reserved to them;

- The American colonies can't at present survey or make land grants from territories beyond the western source of rivers flowing into the Atlantic (i.e., west of the ridge of the Appalachians);

- No one may take possession of these lands without royal permission;

- No private person may purchase "Indian" lands or otherwise treaty with Indigenous peoples;

- "Indians" may dispose of their lands only to the Crown, and only at a public assembly;

- Trading with "Indians" requires a royal licence.

The relevant excerpt from the Royal Proclamation can be found here. On the one hand, it seems to assert Britain's sovereignty over First Nations land; on the other hand, it seems to say that First Nations have rights to the land for as long as they want. If they do want to dispose of any land, the Crown is the only potential buyer.

The Council of Fort Niagara. Officials in London were no doubt oblivious to the traditions of Indigenous–settler relations, and thought that a simple unilateral royal proclamation could settle Indigenous–settler affairs. William Johnson knew better. First Nations weren't subjects of the Crown, but independent nations. The Royal Proclamation would have no authority among First Nations unless First Nations agreed to it. He knew that it needed to be transformed from a unilateral declaration to a multilateral treaty. By now Johnson was free of Jeffery Amherst, and he was arguably the most important British official in British North America. He called together a peace council for the summer of 1764 at Fort Niagara. He made sure that invitations were delivered to First Nations far and wide, along with copies of the Proclamation and strings of wampum, according to traditional practices.

The Treaty of Fort Niagara. When the council was convened, it was reportedly the largest and most representative in history, with 2000 chiefs from two dozen nations, arriving from territories extending from Hudson's Bay to the Missisippi to Acadia. (Some First Nations refused to attend.) The gathering renewed the Covenant Chain of Friendship, added oral promises, and exchanged gifts and wampum belts. A new two-row wampum belt, like the ones that had been presented so many times since the arrival of the Dutch a century and a half earlier, confirmed the treaty. John Borrows has argued (in this pdf) that the Treaty of Niagara, incorporating the Royal Proclamation, the verbal promises, and the two-row wampum, is the fundamental agreement between the British Crown and the First Nations of Canada.

The failed treaty at Detroit. A few weeks later Colonel John Bradstreet met with Indigenous representatives at Detroit to negotiate a peace treaty. It turned out to be unacceptable to both Britain and the First Nations, so it might be ignored, but the reaction to it was telling. When William Johnson saw it, he was dumbfounded: the draft treaty asserted British sovereignty. First Nations certainly had no intention of accepting such an idea, Johnson knew, so it must have been included

from the ignroance of the Interpreter or from some other mistake; for I am well convinced that they [the First Nations] never mean or intend, any thing like it; ... neither have they any word which can convey the more distant idea of subjection, and should it be fully explained to them, and the nature of subordination punishment etc., defined, it might produce infinite harm.

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix. In 1768 William Johnson met representatives of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, each of the Six Nations and Shawnee and Lenape representatives at Fort Stanwix (now a historical monument in Rome, New York). The intent was to settle land disputes and reduce violence between squatters and First Nations peoples between the Appalachians and the Ohio River by a cession of land. The Haudenosaunee, who claimed territory all the way to the Tennessee River, believed they had the right to surrender this land, without the permisson of the First Nations living there. Johnson, himself a land speculator, ignored his conflict of interest. As the simple map below shows (thank you, National Park Service), this Treaty extended British territory way beyond the Proclamation line to include territory south and west of the Ohio River. Correspondingly, it pushed "Indian territory" ever further to the northwest. Johnson didn't actually have the authority from London to reach this agreement, and to many at the time, and to almost everyone since, it looked like a bad idea. The Haudenosaunee collected over £10,000 from Britain for ceding this additional land. (The Shawnee and the Lenape, who lived on this land, didn't accept the treaty. The Shawnee continued to fight for land south of the Ohio until 1774, when, as a result of Lord Dunmore's War, they were forced to concede it. But then the American Revolutionary War placed the land again in dispute among First Nations, British, and Americans.)

The Quebec Act (1774). This Act of the British Parliament extended the boundaries of the province of Quebec very aggressively, to include what's now Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota. A likely reason for this expansion of boundaries is that the British wanted more direct control over this territory in order to forestall settler and squatter invasions and land speculation, and to protect the First Nations there. To the American colonists, however, this was an "intolerable act" and a cause for war.

Significance. Joseph Brant (Thayandanagea), a Mohawk, Wolf Clan, was a leader in one of the last "pan-Indian" movements for Aboriginal land rights before the twentieth century. During his lifetime he was more effective than any other single person at keeping issues of Aboriginal land rights and social justice on the agenda of Canada's colonial rulers. Some have called him an unacknowledged founder of modern Canada. His commitment to Anglican Christianity was a key part of his identity; he was a missionary, worship leader, preacher, Bible translator, church builder, and parish leader.

Early life. Brant grew up in a Christian household, it appears, mainly in Canajoharie (the "Upper Castle") on the Mohawk River. His family was comfortably situated. It was involved with trading, was was professionally connected with William Johnson. When Joseph's sister Molly became William Johnson's wife à la façon du pays, young Brant enjoyed privileged access to Johnson's First Nations and settler social network. He fought for Britain in the French and Indian War, then functioned as a diplomatic emissary for Johnson, and fought again for Britain in Pontiac's War. He attended Wheelock's school in Connecticut, as well as (briefly) an SPG missionary school in Canajoharie. His facility with English and the western elements of his education made him unusually bicultural, an essential qualification for his many diplomatic tasks and for his advocacy on behalf of his people. After two marriages each ending in the wife's untimely death, he married Catherine Adonwentishon, a Mohawk, Turtle Clan, of high clan rank.

Military leadership. Brant was named a Mohawk war chief in 1771. During the American War of Independence, he was the military leader of a volunteer company for the British, and received an officer's commission from the governor of Quebec, Frederick Haldimand. He received no pay, but Haldimand promised to protect Haudenosaunee land rights if the British won the war.

In Canada. When the British didn't win the war, Haldimand nevertheless supported Britain's Haudenosaunee allies. A little later we 'll look at some of the things he did, but for now let's just note that Brant became a recognized leader at a new Haudenosaunee territory at Grand River, which runs from north to south into Lake Erie, west of Lake Ontario. His critics would say that his leadership had an autocratic and self-interested dimension, and his reputation at the Six Nations of the Grand River has been tarnished by his sale to settlers of lands that weren't his to sell. Also, from the end of the American Revolution he was the principal leader of the Western Confederacy of First Nations fighting for American and British recognition of Aboriginal land rights in Ohio country, as we'll consider shortly.

'll look at some of the things he did, but for now let's just note that Brant became a recognized leader at a new Haudenosaunee territory at Grand River, which runs from north to south into Lake Erie, west of Lake Ontario. His critics would say that his leadership had an autocratic and self-interested dimension, and his reputation at the Six Nations of the Grand River has been tarnished by his sale to settlers of lands that weren't his to sell. Also, from the end of the American Revolution he was the principal leader of the Western Confederacy of First Nations fighting for American and British recognition of Aboriginal land rights in Ohio country, as we'll consider shortly.

Anglican leadership. After his first wife died in 1771, Brant lived for a year or two with John Stuart (1740–1811), the SPG missionary at Fort Hunter near Tiononderoge, "the lower castle." Brant had quickly struck up a friendship with Stuart, a tall, warm-hearted Pennsylvanian. Brant tutored Stuart in Mohawk, and regularly acted as his interpreter at church services. The two of them collaborated on translations into Mohawk of the Gospel of St. Mark, an exposition of the Anglican catechism, and a history of the Bible, all published in 1787. Later, at Grand River, Brant arranged the construction of the Mohawk chapel, the oldest Protestant church in what's now Ontario, and seems to have functioned as its principal superintendent.

Revolution, refugees, dispossession

The American Revolution. Many American colonists in the 1770s resented having to pay to protect First Nations beyond the Appalachians. Britain was imposing taxes and financial charges on the American colonists for this purpose among others. They also resented the Quebec Act of 1774 which extended the territory of Quebec way into "Indian country" to give greater protection to the First Nations there. (They also resented the Quebec Act for maintaining French-Canadian culture and for giving Roman Catholics far more rights than they enjoyed in England itself.) In April 1775 war broke out, pitting American rebels or "Patriots," who wanted independence from Britain, against "Loyalists." Governments of the thirteen "original" British American colonies committed themselves to the Revolution. The other British colonies didn't go along (Nova Scotia, St. John's Island [now Prince Edward Island], Quebec, Newfoundland, Rupert's Land, West Florida, East Florida).

First Nations and the Revolution. Different First Nations made different decisions about the Revolution:

- The New England First Nations generally supported the Revolution.

- A Haudenosaunee council at Albany in August 1775 agreed on neutraliity.

- Despite the position of neutrality, individual Haudenosaunee made their own decisions. It's often said that the Oneida and Tuscarora supported the Americans and the other four nations supported the British, but in fact, when we drill down nation by nation, all the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee and all the Seven Fires of Quebec were at least to some extent divided in allegiance. Many served as scouts, guides, and soldiers. Most others sought to remain neutral.

- Joseph Brant, as we've seen, raised a company of Mohawk and settler Loyalist volunteers. His group was vigorously effective at war.

- The Ohio First Nations attempted to remain neutral. Why should they care about a conflict between one white nation against another? But before too long, violent Patriot aggression moved most of them to support the British.