WYH2010HF Christianity 843–1648

Western Christianity in 843

Links and resources

A publicly accessible on-line history course at Washington State University offers some valuable historical introductions, including :

Charlemagne,

the greatest of the medieval kings, and the model of a Christian emperor,

ruled much of western Europe by the time he passed it on to his son Louis

the Pious in 813. Louis was so religious that he had trouble being taken

seriously by the nobles of his realm — and perhaps by his children.

His three sons by his first wife, and a fourth son by his second wife,

fought for his territory even during his life. After his death in 840,

civil war erupted. A battle to decide on the inheritance was fought in

June 841 at Fontenoy in Burgundy. It followed rules anticipating the later

code of chivalry — for instance, the battle took place not on a Sunday,

and after mass. One estimate is that 40,000 died. In the wake, a treaty

was signed at Verdun in 843 by which Charlemagne's empire was partitioned

among the sons. These are the origins of France, Germany, and Italy.

Charlemagne,

the greatest of the medieval kings, and the model of a Christian emperor,

ruled much of western Europe by the time he passed it on to his son Louis

the Pious in 813. Louis was so religious that he had trouble being taken

seriously by the nobles of his realm — and perhaps by his children.

His three sons by his first wife, and a fourth son by his second wife,

fought for his territory even during his life. After his death in 840,

civil war erupted. A battle to decide on the inheritance was fought in

June 841 at Fontenoy in Burgundy. It followed rules anticipating the later

code of chivalry — for instance, the battle took place not on a Sunday,

and after mass. One estimate is that 40,000 died. In the wake, a treaty

was signed at Verdun in 843 by which Charlemagne's empire was partitioned

among the sons. These are the origins of France, Germany, and Italy.

Feudalism. This term is now out of favour, because it tries

to make a very diverse and changing set of political, social, and economic

relationships sound like a monolith. Its general principle is that  Charlemagne

had given grants of land that carried certain obligations to him; the

owners of these lands became the hereditary nobility. Under his weaker

successors these nobles became very independent, and thus Charlemagne's

empire disintegrated into a very diverse set of largely autonomous jurisdictions.

(An important theme of medieval and early modern history is the building

up of nation-states and monarchies out of these independent duchies, counties,

and other jurisdictions.)

Charlemagne

had given grants of land that carried certain obligations to him; the

owners of these lands became the hereditary nobility. Under his weaker

successors these nobles became very independent, and thus Charlemagne's

empire disintegrated into a very diverse set of largely autonomous jurisdictions.

(An important theme of medieval and early modern history is the building

up of nation-states and monarchies out of these independent duchies, counties,

and other jurisdictions.)

Each noble lord and lady have their system of land tenancy and revenues, their own army (raised from the tenants and serfs under their control), their own courtly life (so that aristocratic courts become sponsors and centres of arts and culture), and their own instruments of social control. In theory the nobles swear obedience to the king and become his "vassals", and in turn have their own vassals (the lesser nobility) and serfs (in effect slaves attached to the land). For church history it's important to note that monastic and other church lands are very much a part of systems of land ownership, and that church officials are part of systems of lordship and vassalage. The confused "feudal" connection between the church and the temporal rulers gave rise to the Investiture Controversy, which we'll consider later.

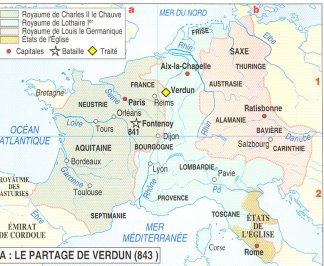

Specific western regions in 843

France. The word began to be used around 1000 for the region where the Frankish people dominated. This very large map represents its diverse jurisdictions, including Normandy, Brittany, Burgundy, Aquitaine, Gascony, and Navarre. The "Spanish marches" ("march"=boundary area), the northern part of the Iberian peninsula recaptured from the Moslems in the early 800s, belonged to the Count of Barcelona, another vassal of the emperor.

Germany. This map shows some its many jurisdictions, notably Saxony, Lotharingia, Franconia, Swabia, and Bavaria.

Italy. This map shows its many jurisdictions, including Lombardy (centred on Milan), Tuscany (centred on Florence), Spoleto, and the patrimony of St. Peter, and in the south, Benevento, Capua, Apulia, Salerno, and Calabria. The exarchate of Ravenna, which had been the seat of Byzantine power of Italy since the days of the Emperor Justinian in the sixth century, was conquered by the Lombards in 751, and came to the pope in 784.

England. From about 500 until the kingdom of England began taking shape in 850, this territory was divided into several independent jurisdictions — traditionally numbered as seven, and thus called the "heptarchy" (Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex), although actually these were not equal in status, and there were additional divisions as well. Here's an easy-to-read map.

Essentials of western Christianity in 843

Monasteries.

These are places of prayer, scholarship, and manual work where life is

organized according to a "Rule" (Latin regula), and their

inhabitants are called "regulars" or monks. By 843 the Rule

of St. Benedict has emerged as the most important monastic rule, although

it comes in several versions. Monasteries own considerable amounts of

property, and are thus prominent landowners and local rulers. Before the

parish system develops, monasteries frequently send itinerating pastors

out into the surrounding countryside to minister to folks.

Monasteries.

These are places of prayer, scholarship, and manual work where life is

organized according to a "Rule" (Latin regula), and their

inhabitants are called "regulars" or monks. By 843 the Rule

of St. Benedict has emerged as the most important monastic rule, although

it comes in several versions. Monasteries own considerable amounts of

property, and are thus prominent landowners and local rulers. Before the

parish system develops, monasteries frequently send itinerating pastors

out into the surrounding countryside to minister to folks.

Papacy. The bishop of Rome is still primarily the bishop of a diocese and a large landowner, but the historical or legendary connection of Rome with Peter and Paul, the abundance of saints' relics found there, the city's heritage as the former capital of the Roman Empire, and its recognition as a patriarchate by the councils of the Church, give the pope more prestige than other western bishops. (The popes usually lived in the Lateran Palace in Rome until 1377, when they usually lived in the Vatican Palace.)

Liturgy. The office liturgy of readings and prayers centred on monasteries and cathedrals, and the mass, or sacrament of the eucharist, were the characteristic worship of the medieval Church. The Frankish kings and the emperor Charlemagne sought to standardize the liturgy. To that purpose they brought the Latin liturgy of Rome into widespread use, adapting it to north-of-the-Alps tastes by mixing in Gaulish and Frankish elements. Benedict of Aniane was particularly notable in the Carolingian liturgical revisions.

Lay leaders. Thomson notes (p. 92) that emperors and kings were often, before the Hildebrandine reforms, seen as having spiritual authority. Nobles and wealthy landowners often made endowments for religious purposes (such as monastic houses and local churches), sometimes setting conditions on their gifts that influenced church policy, and often maintaining a right to patronage (appointing church leaders).