WYH2010HF Christianity 843–1648

Western Christianity 843–1050

Links and resources

See John A. Thomson, The Western Church in the Middle Ages (Arnold, 1998), pp. 3-78).

An introduction to medieval Europe from the University of North Florida.

East central Europe in the tenth century, from the History Text Archive, edited by a Ph.D. from Syracuse University

The English church before the Danish conquest, from Minnesota State University, Mankato; followed by the English Church under Cnut

"The baptism of Rus," from a 1989 book by Paul Steeves

The Bollandists, students of saints' lives

A lecture on the era from Southwest Baptist University

Some resources on the Sermon of the Wolf

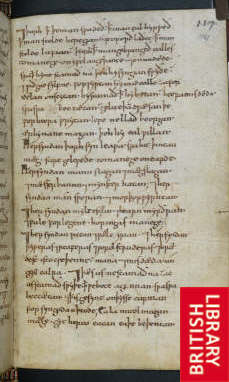

The earliest known

ms of the sermon, from the British

Library

The earliest known

ms of the sermon, from the British

Library

- The text, from Florida State University

- Material on Wulfstan included in this chapter from the emuseum at Minnesota State University, Mankato

- From the online Literary Encyclopedia, written by a scholarly collective, edited by from the University of East Anglia

- A BBC intro to the sermon

A recent biography of Wulfstan.

Your U of T library card can get you Internet access to an article on

another one of Wulfstan's sermons (Joyce Tally Lionarons in The Review

of English Studies 55 (2004) 157ff. Here's part of the abstract:

The textual identity of Old English works in modern print

editions often varies in order to suit the aims of a specific editorial

theory or the purposes of an individual editor. ... [The article also

discusses] the ways in which homiletic texts were received in Anglo-Saxon

England and edited in more modern times.

Popes

Popes of the day in the old Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia

The cadaver synod, 897, from a law professor at the University of Georgia

Sergius III (904-911)

Cardinals of the 10th century, from a Florida International University website

The extension of Christianity

Although the geographical contraction of Christianity in the century after Mohammed is very striking, its extension northward into Europe is equally important.

The conversion of the Slavs

Cyril

(d. 869) and Methodius (d. 884) were sent to Moravia by the

patriarch of Constantinople in 863. They preached in the vernacular (which

was Slavonic) and, more controversially, translated the liturgy into Slavonic.

They proved very successful missionaries. The Moravian mission was later

eradicated, but their posthumous influence extended to Bulgaria, Serbia,

and Russia, where Slavonic remains the liturgical language for Orthodox

and Roman Catholics.

Cyril

(d. 869) and Methodius (d. 884) were sent to Moravia by the

patriarch of Constantinople in 863. They preached in the vernacular (which

was Slavonic) and, more controversially, translated the liturgy into Slavonic.

They proved very successful missionaries. The Moravian mission was later

eradicated, but their posthumous influence extended to Bulgaria, Serbia,

and Russia, where Slavonic remains the liturgical language for Orthodox

and Roman Catholics.

The conversion of Russia

In the 950s,

Princess Olga (c. 890-969), pictured below left, the regent of the

Rus confederation centred on Kiev, visited Constantinople. Before or during

or after that visit, she was introduced to Christianity and converted.

She then attempted, unsuccessfully, to convert her son and others. Her

grandson Vladimir (956-1015) converted to Christianity in  988,

as part of a military alliance with the Byzantine Empire which included

his marriage to the Emperor's sister. He put away his hundreds of concubines,

destroyed pagan temples, built churches and schools, invited missionaries,

and gave alms to the poor. A

more colourful story from the Russian Primary Chronicle is linked

here.

988,

as part of a military alliance with the Byzantine Empire which included

his marriage to the Emperor's sister. He put away his hundreds of concubines,

destroyed pagan temples, built churches and schools, invited missionaries,

and gave alms to the poor. A

more colourful story from the Russian Primary Chronicle is linked

here.

The conversion of Scandinavia. This was a slow process, discussed at some length in the Thomson textbook. Also see this brief BBC summary. The process began with St. Anskar (801-865), the "apostle to the north." The medieval Life of Anskar by a friend and disciple is linked here.

The Vikings

1.

The Vikings. Vikings began to raid the coasts and islands

of western Europe in the late 700s. They continued to be a threat until

about 1050.

1.

The Vikings. Vikings began to raid the coasts and islands

of western Europe in the late 700s. They continued to be a threat until

about 1050.

In the 800s the Vikings

were a Germanic people living in Scandinavia. "Vikings"

may come from a Scandinavian word meaning “pirates”, or maybe

it means “streams”, which are what their boats sailed up, looking

for plunder. The term "Norse" is also used, meaning people from

the north. (The drawing comes from a webpage with

further information about the Vikings.)

Sometimes after their raids, a few Vikings might stay in Britain or Ireland or France or Spain or wherever they might be, and establish base camps for their armies. Some might settle, intermarry, and become Christian; historians call these folks "Normans". Norman settlers around the mouth of the Seine, in what is now called Normandy, reached an agreement with the king of France in 912 by which they would be welcome in the land if they became Christian and recognized the king. They soon adopted French ways and the French language. In 1066 the duke of Normandy led an invading army into England, where he became king. In 1071 other Normans invaded Sicily. Normans there and in southern Italy would become important protectors of the papacy in the following decades.

Cluny

Over time, monasteries

had a way of growing lax in discipline, fervour, and piety. In the tenth

century there began the first in a series of monastic reform movements.

The earliest important reform in the Benedictine tradition, and perhaps

the most historically important of all, was the abbey of Cluny in Burgundy.

It was founded

in 910 (see the original charter) by the duke of Aquitaine. It founded

several daughter houses, and departed from the Benedictine tradition by

exercising authority over them, thus creating a centralized monastic order.

It was highly blessed in its abbots, whose wisdom, piety, and leadership

gave the abbey its real importance. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries

it was arguably the second most important centre of western Christianity

after Rome. The monastery was suppressed in 1790 during the French Revolutionary,

but parts of some of the buildings remain.

Over time, monasteries

had a way of growing lax in discipline, fervour, and piety. In the tenth

century there began the first in a series of monastic reform movements.

The earliest important reform in the Benedictine tradition, and perhaps

the most historically important of all, was the abbey of Cluny in Burgundy.

It was founded

in 910 (see the original charter) by the duke of Aquitaine. It founded

several daughter houses, and departed from the Benedictine tradition by

exercising authority over them, thus creating a centralized monastic order.

It was highly blessed in its abbots, whose wisdom, piety, and leadership

gave the abbey its real importance. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries

it was arguably the second most important centre of western Christianity

after Rome. The monastery was suppressed in 1790 during the French Revolutionary,

but parts of some of the buildings remain.

The papacy

The strong connection of the papacy with the Franks during the time of Charlemagne declined, as the Empire did, after his death. Italy was also destablized by the Viking invasions . The 900s are often considered the historic low point of the papacy, when it was captive to the rivalries and politics of the important families of Rome and central Italy. Six popes took office between 891 and 898, three of whom were murdered. During the period 904-964 the intriguing Theophylact family was central to its fortunes; some popes were the lovers or illegitimate children of two women, Marozia and Theodora, from which this papal period is sometimes called the "pornocracy". Another branch of the same family, the Crescenzi, exercised similar influence from 976 until they were forced out of Rome by the emperor Henry II in 1014. Another branch of the family, the Tusculani, took control in 1012 with the election of Benedict VIII, who was followed by his brother John XIX, who was not ordained before becoming pope, and then their nephew Benedict IX, who sold the papacy in 1045, reclaimed it in 1047, and was exiled in 1048.

Local worship

The idea of local churches was late to develop. The nobility might build cathedrals for the bishops they appointed, and might endow monasteries for those with a vocation in that direction, and those who sought masses or baptisms or pastoral ministrations were expected to repair there.

Chapels. Clergy in monasteries, as we have seen, might itinerate around the countryside and say masses from time to time in local communities. Sometimes chapels would be built for them. They were strictly adjuncts to the monastery, however. They seldom had baptismal fonts, for instance, since baptisms took place in the monastery church.

Shrines, martyria, basilicas. Places of worship were also built to honour relics and serve as places of special holiness. These might become destinations for pilgrimage.

Proprietary churches. These were private churches owned

by a landlord (or a monastery). These developed in the eighth and ninth

centuries as manors were built by local gentry (not nobles) around Europe

and Britain, and the lord of the manor was often the propietor. The proprietor's

motives might include piety, prestige, and family tradition. In Anglo-Saxon

England, one who built a church might be accepted as a thegn or lord.

The family

from generation to generation maintained ownership and control, appointed

the clergy, and received the revenues. The proprietary church, or its

revenues, or the right to appoint its priest (called an "advowson"),

could be bought and sold like any other real property. (The picture shows

the Anglo-Saxon tower of Bosham church, Sussex.

The family

from generation to generation maintained ownership and control, appointed

the clergy, and received the revenues. The proprietary church, or its

revenues, or the right to appoint its priest (called an "advowson"),

could be bought and sold like any other real property. (The picture shows

the Anglo-Saxon tower of Bosham church, Sussex.

Parish churches. The Hildebrandine reformers viewed the proprietary church, under the control of a layperson, as an abuse. In the late 1000s and 1100s most proprietary churches came into the possession of the bishops (sometimes by gift, sometimes by sale, sometimes by expropriation) and became parish churches, which are, in away, proprietary churches where the bishop is the proprietor. This was the system promoted by Gregory VII. A parish church was under the control of the bishop, was in principle independent of lay influence, served a local geographical territory with identifiable parish boundaries, had an endowment and a steady revenue system through tithes, fees, and offerings, and had a priest with full job security who was accountable to his ecclesiastical superiors and not to any layperson.

Penitence and penance

Sarah Hamilton in The Practice of Penance, 900–1050 (Boydell, 2001), seeks to revise the usual account. The standard view is that private (monastic) penance originated in sixth-century Celtic monasticism, where religiously committed layfolks and monks made their confession as part of a spiritual direction, whereas public (liturgical) penance developed in the late 700s, when Carolingian bishops disciplined prominent persons who had sinned grievously. Then (according to this view) in the 1100s the practice of penance transmogrified into a sacramental act of contrition, done "publicly" in church buildings but "privately" in confessional boxes out of earshot. Hamilton's study suggests that the monastic and liturgical practices didn't at all remain strictly distinct in the 900s and 1000s. On the contrary, they strongly influenced each other. The influence of the monks was huge, as they wrote liturgies, taught the clergy, and administered pastoral care. Many bishops supported these new developments in the practice of penance as a valuable reform. Penance was becoming a valuable tool of pastoral care and social reconciliation. More changes were yet to come; the high middle ages saw the development of "one-stop" penance — confession, assignment of penance, and absolution, all in one event.