WYH2010HF Christianity 843–1648

From 1100 to 1270

Links and resources

General- The Internet Medieval Sourcebook on the Crusades; bibliographies and links to documents are here.

- Ms. Weid, a school teacher in Missouri, has a huge site on the First Crusade

- A very usable website on the First Crusade maintained by an Australian/British medical editor with an interest in medieval history

- A lecture by Lynn Nelson, a retired professor at the University of Kansas on the First Crusade

- The crusades, a treasure-trove of links from Manchester University Press

- Art history of the crusades, from the Metropolitan Museum, New York

A virtual course on the crusades given at Boise State by Dr. Skip Knox

- The First Crusade

- The kingdom of Jerusalem

- Islam during the crusades

- The Second Crusade

- The Third Crusade

- The Fourth Crusade

- The Fifth Crusade

- The later crusades

Sources for the First Crusade

- Urban II, the speech at Clermont declaring the First Crusade, 1095, in five versions

- Sources for Peter the Hermit's part of the First Crusade

- Sources for the Constantinople part of the First Crusade

- Sources for the Antioch part of the First Crusade

- Sources for the Jerusalem part of the First Crusade

- Some primary source documents from the website of the modern Knights Templar order.

The Fourth Crusade

- Villehardouin (died ca. 1213) on the Fourth Crusade

- Microsoft Word document of several sources, from the University of Leeds

- A letter from the sixth crusade

- The memoirs of Joinville, on the disastrous seventh crusade

- Extract of an Arab account of the crusade of St. Louis

The crusades

The First Crusade (1095–1099)

IN

1095, the Christian emperor in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) asked

the Pope for help from western Christians to defend the Church from pagan

Turks. Perhaps this wasn't a good idea. The request changed the course

of history. On Nov. 27, outside the cathedral in Clermont, France, Pope

Urban II preached a crusade. Thousands and thousands responded, at great

cost and personal sacrifice. Over the next few years they made their way

to Constantinople, either overland through Hungary or by sail across the

Adriatic and then through Serbian territory (see

the map), and then down the coast of Asia Minor to Syria. There was

no commander-in-chief, and rivalries among the European leaders were intense

and frequently bitter. The loss of life among Moslems, Jews, and Christians

was enormous. Crusaders finally

IN

1095, the Christian emperor in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) asked

the Pope for help from western Christians to defend the Church from pagan

Turks. Perhaps this wasn't a good idea. The request changed the course

of history. On Nov. 27, outside the cathedral in Clermont, France, Pope

Urban II preached a crusade. Thousands and thousands responded, at great

cost and personal sacrifice. Over the next few years they made their way

to Constantinople, either overland through Hungary or by sail across the

Adriatic and then through Serbian territory (see

the map), and then down the coast of Asia Minor to Syria. There was

no commander-in-chief, and rivalries among the European leaders were intense

and frequently bitter. The loss of life among Moslems, Jews, and Christians

was enormous. Crusaders finally  captured

Jerusalem itself from the Moslems. All those inside the walls, men, women,

and children, were butchered. On Christmas day, 1100, a French leader

named Baldwin (French "Baudouin") was made king (see

left). Later a Latin cleric was made bishop. (The blood-red

cross above right is "the Jerusalem Cross" or "Crusader

Cross", emblem of the Templar Crusaders.)

captured

Jerusalem itself from the Moslems. All those inside the walls, men, women,

and children, were butchered. On Christmas day, 1100, a French leader

named Baldwin (French "Baudouin") was made king (see

left). Later a Latin cleric was made bishop. (The blood-red

cross above right is "the Jerusalem Cross" or "Crusader

Cross", emblem of the Templar Crusaders.)

Among the principles of the Crusade: (1) the killing of heathen was declared to be no sin; (2) the pope declared the crusade a holy cause for God, and promised absolution of all sin for those who completed the crusade; (3) the pope promised to excommunicate those who committed themselves to the crusade but turned back prematurely; (4) popes became part of the military structure of Europe; (5) divisions among Christians were escalated; (6) by the time the crusades were completed, the reputation of Christians for butchery and perfidy was permanently established in the east.

The Second Crusade (1145–1148)

The crusading state of Edessa (in what is now eastern Turkey), founded in the first crusade, fell to the Seljuk Turks in 1144. Pope Eugenius III declared a crusade in 1145. Unlike the First Crusade, this one was led by kings: Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. Their armies were defeated by the Seljuks in what is now Turkey. Surviving crusaders proceeded to besiege Damascus, and were defeated. Buoyed by their success, the Seljuks captured most of the crusading state of Antioch as well, and went on to unify most of the Muslim world from Syria to Egypt. There was, however, a small success when English crusaders on their way to the Holy Land helped capture Lisbon from the Moors (the Muslim empire in what is now Spain and Portugal).

The Third Crusade (1189–1192)

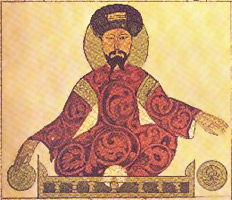

A Kurd named  Saladin,

pictured right, in an almost contemporary image,

became sultan of Syria in 1174, ending Seljuk control

there and beginning the Ayyubid dynasty. A powerful ruler, he eventually

controlled Egypt and North Africa as well. He initially left the Crusaders

alone, but after several raids by the rogue pirate Raynald of Châtillon,

he attacked the kingdom of Jerusalem and destroyed the Crusader army at

the Battle of Hattin, 1187, the turning-point in Crusading history. Within

a few months he had reconquered most of the crusading states. It is said

that Pope Urban III collapsed when he heard the news, and later died.

His successor Gregory VIII proclaimed the third crusade. The Emperor Frederick

Barbarossa took up the cross in March 1188, but was killed in a riding

accident a year later in Turkey, and most of his army died of plague.

France and England collected a "Saladin tithe" to support the

Crusade. King Richard

Saladin,

pictured right, in an almost contemporary image,

became sultan of Syria in 1174, ending Seljuk control

there and beginning the Ayyubid dynasty. A powerful ruler, he eventually

controlled Egypt and North Africa as well. He initially left the Crusaders

alone, but after several raids by the rogue pirate Raynald of Châtillon,

he attacked the kingdom of Jerusalem and destroyed the Crusader army at

the Battle of Hattin, 1187, the turning-point in Crusading history. Within

a few months he had reconquered most of the crusading states. It is said

that Pope Urban III collapsed when he heard the news, and later died.

His successor Gregory VIII proclaimed the third crusade. The Emperor Frederick

Barbarossa took up the cross in March 1188, but was killed in a riding

accident a year later in Turkey, and most of his army died of plague.

France and England collected a "Saladin tithe" to support the

Crusade. King Richard  I

"the Lionheart" of England, pictured

left, led an English and Norman army to the eastern Mediterranean,

where they took Cyprus from the Eastern Christians. With the French and

the Germans, he recaptured Acre in 1191. The Crusaders did not, however,

recapture Jerusalem; by a treaty between Richard and Saladin in 1192,

the Muslims retained control of Jerusalem, but unarmed Christain pilgrims

could visit the city.

I

"the Lionheart" of England, pictured

left, led an English and Norman army to the eastern Mediterranean,

where they took Cyprus from the Eastern Christians. With the French and

the Germans, he recaptured Acre in 1191. The Crusaders did not, however,

recapture Jerusalem; by a treaty between Richard and Saladin in 1192,

the Muslims retained control of Jerusalem, but unarmed Christain pilgrims

could visit the city.

The military hostilites between Richard and Saladin were chivalrous and respectful; when Richard was wounded, Saladin offered his personal physician (Muslim medicine was the most advanced in the world).

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204)

At first Pope Innocent III's call in 1198 for a fourth crusade was ignored.

But preachers generated popular interest, and leaders of states began

seeing opportunities for personal advantage. The ostensible goal was to

recapture Jerusalem, and the strategy now was to attack Egypt first, where

the sultan's power lay. Venice contracted to transport crusaders to Egypt,

but when the crusaders couldn't pay the full amount agreed, Venice convinced

them to attack the Catholic city of Zara in Dalmatia, and hand it over

to Venice (1202). The pope then excommunicated the Venetians and the crusaders.

After this, one Alexius Angelos, the son of a deposed Byzantine emperor,

easily persuaded the Venetians to divert the crusaders to  Constantinople

and capture the city, where Alexius could be put on the throne, and the

Venetians could gain considerable material profit. This they did in 1203.

The new emperor Alexius was, however, strangled by a usurper, and anti-Latin

factions frequently provoked the crusaders, who attacked, sacked, and

burned Constantinople in 1204, torturing and massacring a considerable

part of the population, and raping girls and boys. The Latin Empire of

Constantinople was then established, with Baldwin of Flanders and a Venetian

as patriarch. Land was distributed to the Latins, particularly the Venetians.

(See

Delacroix' painting of 1840, now in the Louvre.) (Constantinople was

recaptured by the Byzantines in 1261.)

Constantinople

and capture the city, where Alexius could be put on the throne, and the

Venetians could gain considerable material profit. This they did in 1203.

The new emperor Alexius was, however, strangled by a usurper, and anti-Latin

factions frequently provoked the crusaders, who attacked, sacked, and

burned Constantinople in 1204, torturing and massacring a considerable

part of the population, and raping girls and boys. The Latin Empire of

Constantinople was then established, with Baldwin of Flanders and a Venetian

as patriarch. Land was distributed to the Latins, particularly the Venetians.

(See

Delacroix' painting of 1840, now in the Louvre.) (Constantinople was

recaptured by the Byzantines in 1261.)

Further crusades

- The children's crusade (1212). A German shepherd boy persuaded several thousand children to go on a crusade. They got as far as Italy, where many were sold into slavery. Recent scholarship suggests that no such crusade happened. There may have been a religious protest movement of peasants, called in contemporary sources pueri, a word which can also mean children.

- The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221). In 1213 Pope Innocent III's bull Quia maior called for a fifth crusade, and the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) passed several decrees on the matter. The crusaders failed to recapture Jerusalem and disastrously failed to capture Cairo, but, with many deaths, won the port town of Damietta in Egypt.

- The Sixth Crusade (1228–1229).

The Emperor Frederick II managed to sign a truce with the sultan

of Egypt, who wanted to keep Jerusalem from his nephew. Frederick entered

Jerusalem and crowned himself king, and then went home. Jerusalem fell

to the Mamluks in 1244. (The fifth and sixth crusades are sometimes

counted as one.)

- The Seventh Crusade (1248–1254). King Louis IX of France (St. Louis) and 20,000 soldiers took Damietta, and tried unsuccessfully to take Cairo. Many of his troops died of starvation and disease. Louis contracted dysentery, but was cured by a Muslim physician, then released on payment of a ransom. He made an alliance with the rulers of Egypt who allowed him to rebuild the old crusading cities, but when his money ran out, he went home.

- The Eighth Crusade (1270). This was another crusade led by King Louis IX. He sailed to the African coast with his army, and he and most of his men died. His last word: "Jerusalem."

- The Ninth Crusade (1271–1282). As the Mamluks were recapturing the last remaining crusading cities, Prince Edward of England and Charles of Anjou, sailed to Acre, where they reconciled some factions. Edward returned to England to become king, and Charles took control. Charles and the Venetians, with the pope's permission, then tried to recapture Constantinople from the Byzantine Christians, but Charles was prematurely forced to return home because of a political crisis (the Sicilian Vespers).

- The end of the crusading states. In 1291, after Christians killed some Muslim merchants and refused to make restitution, the Sultan Khalil successfully besieged Acre, and killed 60,000 prisoners, and then recaptured all the rest of the crusaders' territory. 200 years of crusades had finally failed to achieve anything other than a great deal of death and destruction.