WYH2010HF Christianity 843–1648

Divergence 1270–1515

Links and resources

Documents on the Great Schism

- The cardinals in revolt

- The University of Paris on the schism

The Black Death

Documents on the plague from the University of Virginia

The onset of the plague in Florence, from Boccaccio's Decameron

A readable short history of the plague by Skip Knox for Boise State University

A lecture on the black death by Lynn Harry Nelson, University of Kansas.

A discussion of the black death in History Magazine

Ordinances for sanitation during the black death, for a small town near Florence

Medieval English sources for the black death, from Manchester University Press

Shifting explanations for the black death, from History News Network, dated April 2005

PDF-format review of a book on the black plague by Samuel Cohn

Another review of the same book, not PDF

A review of a book about the plague by Norman Cantor

Thomson's The Western Church in the Late Middle Ages suggests that the Late Middle Ages were a period of divergence in several respects.

- The lay rulers of western Europe were growing increasingly strong,

while the papacy's

temporal powers (as opposed to its administration provision of

ecclesiastical affairs) were growing weaker. The kidnapping

of Pope Boniface VIII by a French military squad in 1303 at Anagni

symbolizes this development. (The pope, not the kidnapping, is pictured

left.) The popes therefore often had to bend policies to accommodate

regional interests, especially in what Thomson calls "the age of

concordats", or agreements between the papacy and specific lay

rulers. The

Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges of 1438 is a good example for France.

while the papacy's

temporal powers (as opposed to its administration provision of

ecclesiastical affairs) were growing weaker. The kidnapping

of Pope Boniface VIII by a French military squad in 1303 at Anagni

symbolizes this development. (The pope, not the kidnapping, is pictured

left.) The popes therefore often had to bend policies to accommodate

regional interests, especially in what Thomson calls "the age of

concordats", or agreements between the papacy and specific lay

rulers. The

Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges of 1438 is a good example for France.

- The Great Schism created two papacies (1378-1409) and then three papacies (1409-1417, with continuing conflicts after that). Each papacy was recognized by a different group of lay powers.

Theological

thought diversified. The Ockhamist tradition moved in a different direction

from the Thomist, and other theologians such as Thomas Bradwardine,

John Wyclif (pictured right), and Gregory Rimini were different

yet. The papacy didn't always have the power to enforce standards of

orthodoxy across Christendom, but depended on the lay power, which might

(as in the case of Wyclif) protect divergent thinkers.

Theological

thought diversified. The Ockhamist tradition moved in a different direction

from the Thomist, and other theologians such as Thomas Bradwardine,

John Wyclif (pictured right), and Gregory Rimini were different

yet. The papacy didn't always have the power to enforce standards of

orthodoxy across Christendom, but depended on the lay power, which might

(as in the case of Wyclif) protect divergent thinkers. - Mysticism became much more prominent in the 1300s and 1400s, not necessarily because there were more mystics, but because there was a greater market among a literate laity for mystic writers. Thomson calls this "do-it-yourself religion", another sign of religious divergence.

- There were no great reform movements across the Western Church, as there had been with Cluny and the Cistercians. Reform movements were local. Examples are the Lollards in England and the Hussites in Bohemia, whose reform ideology was regarded as heresy by Church authorities.

- Universities proliferated, the great majority of them now more national than supra-national in appeal and character. (Paris was a notable exception.) Graduates who entered positions of church leadership were thus more likely than before to have a regional outlook.

The Black Death

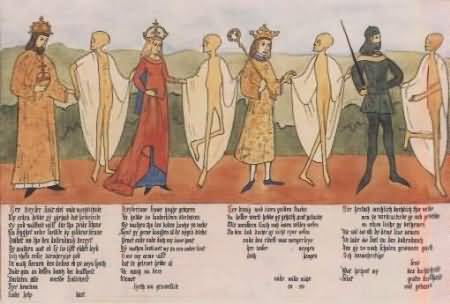

In 1347 three trading

galley-ships arrived at Messina, Sicily, all of whose crew members were

either dead from the plague or infected with it. Over the next four years

it spread across Europe. It's believed that about a third of the population

of Europe was annihilated. (Population in 1347: 75 million. Population

in 1352: 50 million.) The black death killed within a week, sometimes

within a day. Victims frequently developed black blotches in their skin,

whence the name "black death." It's usually believed that the

black death was usually bubonic plague (>"bubo", swelling),

carried by the fleas on rats, or pneumonic plague, spread by coughing,

but some historians of medicine suspect that it was pulmonary anthrax,

and there are other theories as well. Pictured: a 1411 picture

of two victims of the black death.

In 1347 three trading

galley-ships arrived at Messina, Sicily, all of whose crew members were

either dead from the plague or infected with it. Over the next four years

it spread across Europe. It's believed that about a third of the population

of Europe was annihilated. (Population in 1347: 75 million. Population

in 1352: 50 million.) The black death killed within a week, sometimes

within a day. Victims frequently developed black blotches in their skin,

whence the name "black death." It's usually believed that the

black death was usually bubonic plague (>"bubo", swelling),

carried by the fleas on rats, or pneumonic plague, spread by coughing,

but some historians of medicine suspect that it was pulmonary anthrax,

and there are other theories as well. Pictured: a 1411 picture

of two victims of the black death.

The black death returned every few years for the next several decades.

Religious consequences of the black death include:

- Persecutions and slaughters of Jews and other minorities, on the ignorant suspicion that they might have been poisoning wells or otherwise causing the problem.

- The Church's ineffectiveness in stopping or healing the black death promoted some cynicism about the Church's religious powers.

- Flagellants appeared in large groups, beating themselves in self-administered penance. Considered by some living martyrs, they could wield strong local influence. The Church tried to suppress them.

- Those living in monasteries were especially vulnerable, because of

the increased vulnerability to contagious disease. The monasteries never

entirely recovered. Shortages of clergy resulted. (Three archbishops

of

Canterbury, including

Thomas Bradwardine, died of the black death in 1348-1349.) New recruits

to the clergy were observed by some contemporaries to be less able and

less morally conscientious than their predecessors.

Canterbury, including

Thomas Bradwardine, died of the black death in 1348-1349.) New recruits

to the clergy were observed by some contemporaries to be less able and

less morally conscientious than their predecessors. - A pessimistic and anxious mood arose in Europe, seen particularly in images of death in art (an example is pictured here); poetry about the death and wrath of God, such as Dies irae; and devotional tracts on ars moriendi, or the art of dying. (See the next webpage for a further discussion.)

Late medieval theology

Late medieval theology can be studied:

- for its own sake; or

- as a reaction against the theology of the high middle ages, especially the Thomistic synthesis. The twentieth-century neo-thomists read it as a very unfortunate theological decline; or

- as an anticipation of the Reformation, and perhaps especially of Martin Luther. [Depending on the historian, Luther is held to have (a) rejected late medieval theology, (b) developed it, or (c) interpreted it erroneously.]

A division frequently drawn in medieval theology is between

- the via antiqua, the "old way," which recognizes

the capacity of human

reason

to know the world apart from revelation. Thomas Aquinas is the best

example; Duns Scotus in the following century is another.

reason

to know the world apart from revelation. Thomas Aquinas is the best

example; Duns Scotus in the following century is another. - the via moderna, the "modern way," which questions the reasonableness of faith, and rejects the philosophical approach which Thomas had accepted. William of Ockham (pictured right) is the best example.

However, late medieval theology is too diverse to be comprehended within two simple categories.

Late medieval theology is frequently subjected to caricature or over-generalization in histories of theology. A more careful work is Steven Ozment, The Age of Reform 1250-1550 (Yale, 1980); and an excellent work on a specific late medieval theologian (Gabriel Biel) is Heiko Obermann, Harvest of late medieval theology (Harvard, 1963) (see a book review).

Gabriel Biel (d. 1495)

Biel was born in Speyer, in Bavaria, received his B.A. from Heidelberg in 1435, and subsequently studied at Erfurt. He was attracted to the devotio moderna and joined the Brethren of the Common Life in the 1460s. He taught at Tübingen.

Biel is a late medieval nominalist theologian, who holds the following views.

- God can do anything which does not involve logical contradiction (this is his potentia absoluta), but has freely established laws for himself to follow (this is his potentia ordinata). He has chosen these laws in congruity with his loving and merciful character.

- Thus God doesn't will what is good or right (he would then be subject to some prior principle). Rather, what he wills, is right. The will of God is the first principle of all justice. (Natural law is the second principle; positive human law is the third principle.)

- The potentia ordinata could not have been predicted by reason. Revelation is necessary. Faith cannot be grasped by reason. The facts of faith are not logically linked. Faith therefore relies on an external authority, namely, Scripture, Church, tradition, or preacher.

- History moves from the mercy of the Incarnation to the justice of the last judgment. Our acceptation by God, and our participation in the final beatific vision, requires our being just. We cannot be justified without the grace of God. However, God has obliged himself to infuse his grace into anyone who has done his very best (facere quod in se est) to renounce sin and love God for God's sake. The first justification takes place in baptism, which infuses sanctifying grace but does not eliminate our liability to sin (fomes peccati or 'tinderbox of sin'). The second justification is centred on the sacrament of penance, seen as an act of Christ, not the act of the priest.

- Predestination is God's foreknowledge that the believer will do his very best, and will therefore be justified.

- None of us can be sure of our salvation, since we can't know whether we're in a state of grace, nor whether we will persevere to the end.

Luther, who will also study at Erfurt, will react sharply against Biel's view of justification, which he will interpret as a species of the Pelagian heresy (over-valuing human will, under-valuing divine grace). However, he will share, indeed exceed, the nominalists' high estimation of Scripture and tolerance for paradox.

The Age of Concordats Gordon Belyea

- Secular rulers become more assertive. With the Great Schism and the conciliar movement, the Papacy saw its claims to universal authority in the church challenged, at least on the administrative and jurisdictional levels. Secular rulers were more assertive in claiming and assuming control over their respective lands, and in insisting on preferment of their own nominees to ecclesial positions, including the College of cardinals. The papacy had to come to terms with this changing circumstance, which it did through a series of concordats with individual secular rulers. Practical management of the universal church would increasingly devolve to the national level, to become effectively under lay control.

- The concordats established during the 15th and early 16th century saw lay rulers win important gains in their ability to influence ecclesiastical appointments and to control the payment of taxes (e.g., for annates), and witnessed the circumscribing of the powers of ecclesiastical courts. Marriage law and the penitential system remained firmly in the church's control, however. The former meant that the church still played a vital role in regulating political marriages; the latter was a means by which pastoral oversight could continue to be offered to Christians in an increasingly splintered Christendom. The overall willingness of lay rulers to acknowledge the theoretical supremacy of the papacy may well reflect their own concern not to be hoist on their own petard: lay monarchies could be subject to similar temporal challenges as those with which the papacy was being faced.

- Reform proposals were brought forward during this period,

but were subordinated to political struggles. Any impetus for reform

came from the localities; centralised reform of the ecclesial bureaucracy

faced insuperable obstacles from vested interests. The papacy, particularly

under the Borgias, had neither the means nor the incentive to push for

reforms similar to those seen in the 11th century. Beyond its spiritual

concerns, it was enmeshed in the European powers' struggles for control

of the Italian peninsula. The popes were very much monarchs - the finances

required to maintain the administrative bureaucracy of the church required

them to have territorial possessions, with the court and the trappings

that accompanied it. The papacy did not have the advantage of building

a hereditary dynasty, though rampant nepotism in the appointment of

cardinals offered some means of aspiring to this, which Alexander VI

most certainly did. Maintenance of visible power was both seen as a

necessity in dealing with the other powers of Europe, as well as being

undoubtedly a function of vanity. In any case, it certainly meant that

the papacy had become greatly secularized by this point which, oddly

enough, may not have greatly affected its spiritual authority.