Indigenous Christians

WYH3271HS Winter 2017 February 16, 2017

Links

Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports (mostly pdf's)

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the TRC Final Report

The Survivors Speak: A Report

The Role of the RCMP during the Residential School System

Canadian public opinion on Indigenous peoples

TRC Calls to Action

What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation

The Indigenous Studies Portal at the University of Saskatchewan has links to a wealth of resources on Indigenous languages.

Statistics Canada census data on Aboriginal languages today.

Statistics Canada on Indigenous cultural categories today.

First Nations and First Languages from the University of Ottawa.

Aboriginal sections of the Canadian Constitution from UBC.

Aboriginal and Northern Affairs Canada has a great deal of historical and descriptive material.

The same department has profiles of First Nations across Canada.

Wikipedia has entries on Canada's three Aboriginal groups: First Nations, Inuit, Métis.

Statistics Canada has demographic information.

The Canadian Studies Program of the government of Canada's Department of Heritage has considerable study materials.

The Indigenous Studies Portal at the University of Saskatchewan is a treasure trove of resources.

The First Nation / Native American / Inuit Directory gives links to the web portals of Indigenous groups.

UBC has several webpages on Aboriginal Foundations.

The Royal Commission Report on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), 1996.

General changes in the situation of Indigenous peoples

The Canadian Constitution identifies three categories of Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples: First Nations (who come under the Indian Act), Métis, and Inuit. The social, legal, and cultural situation of all three categories has changed dramatically since the 1960s.

Before the 1960s

Often through subterfuge or threat, First Nations peoples east of British Columbia had signed land treaties, and their communities were consigned to reserves, often on marginal land.

Often through subterfuge or threat, First Nations peoples east of British Columbia had signed land treaties, and their communities were consigned to reserves, often on marginal land. - First Nations peoples were subject to the Indian Act. Indian agents had considerable power over Native commerce, movement, and lifestyle.

- First Nations people had few political rights, such as the right to vote.

- Native ceremonies were banned.

- Traditional First Nations governments were banned.

- First Nations people could not retain a lawyer to file claims against Canada, among other restrictions on right to counsel.

- First Nations children could be forced to attend residential schools, under unsanitary conditions, and subject to widespread abuse.

- Government policy was the assimilation of First Nations peoples. Many kinds of cultural expression, including Native languages, were restricted, especially in residential schools.

.After the 1960s

- Status Indians received the right to vote in federal elections in 1960. By 1969 they had also received the right to vote in all provinces and territories.

- Legal cases established that Indigenous peoples came under the Canadian Bill of Rights of 1960, and were protected from discriminatory treatment at law on the basis of their Aboriginal identity.

- In 1969 the federal government took over Indian residential schools from church administration. It decided to phase out all these schools, against some resistance from the Roman Catholic Church and from some Indigenous communities. The last school to close was Gordon's School in Punnichy, Saskatchewan, in 1996, which by then was simply a student hostel.

- In 1969 the Trudeau government issued a white paper, proposing the repeal of the Indian Act and the assimilation of First Nations peoples. Views of First Nations peoples had been largely ignored. The white paper galvanized First Nations people into political action and advocacy.

The Calder decision of the Supreme Court in 1973 helped open the way to the treaty-making in British Columbia, where no previous treaties had been made, and governments had argued that Aboriginal rights had been extinguished by colonization. The Nisga'a Agreement of 2000 was ground-breaking.

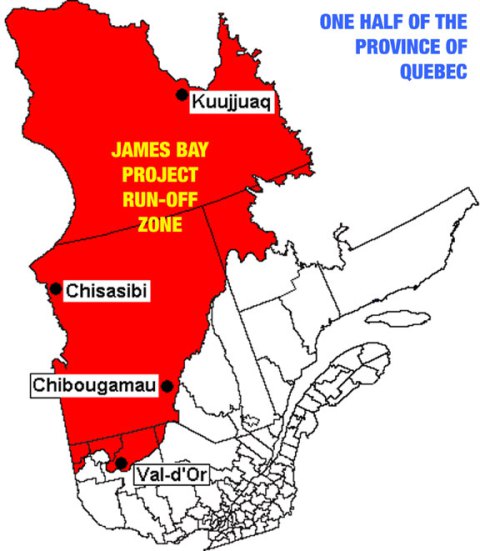

The Calder decision of the Supreme Court in 1973 helped open the way to the treaty-making in British Columbia, where no previous treaties had been made, and governments had argued that Aboriginal rights had been extinguished by colonization. The Nisga'a Agreement of 2000 was ground-breaking. - The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement of 1975, triggered by Hydro-Quebec's desire to build large dams, became a prototype for later agreements with First Nations peoples. It dealt with land claims, financial compensation, environmental protection, education, social services, and self-government.

- In 1985 the Indian Act was amended to void 'enfranchisement', a process by which status Indians could lose status under the Indian Act. It also allowed status Indian women who 'married out' (to non-Indians) to retain their status. A further provision, which provided that after two generations of 'marrying out' status was lost, would have largely effected the legal assimilation of First Nations people in a few generations, but this provision was partly corrected by a further amendment to the Indian Act in 2011, forced by a ruling of the Supreme Court in 2009 in McIvor v Canada. .

- The Sparrow decision of the Supreme Court in 1990 affirmed Aboriginal and treaty rights under the Canadian Constitution.

- The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, from 1992 to 1996, triggered by the Oka crisis of 1990, recommended sweeping changes in the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the government of Canada. Its direct constitutional and political results were rather few, but its 4000-page report has been influential in re-setting the historical narrative of settler-Indigenous relations.

- The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement of 2006 was the result of the largest class action lawsuit in Canadian history, involving approximately 85,000 residential school survivors. This was a way of dealing with thousands of individual lawsuits by survivors who had suffered horrific abuse in the residential school system. The Agreement provided for compensation, an apology by the federal government, and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, mandated by the IRSSA (above), met from 2008 to 2015, reviewed a huge amount of documentation and heard from 6500 witnesses. It issued 94 recommendations.

- In the 2015 federal election, a historically large proportion of First Nations people voted, and ten First Nations candidates were elected to Parliament.

- First Nations populations appear to be increasing. In 1981 Statistics Canada reported 293,000 status Indians and 75,000 non-status Indians. In 2001 Statistics Canada reported 558,175 status Indians and 50,675 non-status Indians, but cautioned that these numbers probably under-represented the reality.

Indigenous peoples and the churches

Christian identification

- In the 2001 census, of 1,359.010 respondents self-identifying as Aboriginal, 42% identified as Roman Catholic, 22% as some form of Protestant, 28% as "none", and 2% as following Aboriginal spirituality. There are numerous issues with the data, including the fact that not all reserves participated in the census, some reserves reported data quality issues, and the census offered only one choice of religion (e.g., a respondent couldn't choose both "Protestant" and "Aboriginal spirituality").

- The National Household Survey of 2011 indicates that among Indigenous peoples, 506,000 associate with Roman Catholicism, 134,000 with the Anglican Church, 59,000 with the United Church, and 36,000 are Pentecostal. About 63,000 associate with Aboriginal spirituality. One in five claim 'no religion'.

- 'Métis' is a contested term, but in the historic sense of persons descended from mixed Aboriginal and European parentage in the Canadian North West, dating back to when the Hudson's Bay Company controlled this territory, most 'Métis' are Roman Catholic.

- Most Inuit are Anglican, and many are Roman Catholics. Traditional ways, once differentiated from Christian belief and practice, are now more often understood as compatible.

Justice and Leadership

- In the Anglican Church of Canada, there have been nine Indigenous bishops, and at present there are approximately 130 Indigenous priests. There is a National Indigenous Anglican Bishop (Mark MacDonald). An Anglican Council of Indigenous Peoples was established by General Synod in 1975; it has 20 members, all Indigenous. A national gathering of Indigenous Anglicans takes place every three years, and is called the Sacred Circle. General Synodo has a department of Indigenous Ministries. An apology for the Anglican role in Indian residential schools was offered by the then Primate, Archbishop Michael Peers, in 1993, to the National Native Convocation, and is considered an important event in re-setting relationships.

- The Roman Catholic Church in Canada has not apologized for residential schools, on the stated grounds that, as a unit, it did not participate in them. Instead, individual dioceses and religious orders participated in them. About 70% of compulsory residential schooling in Canada was administered by various parts of the Roman Catholic Church. Pope Benedict XVI expressed sorrow for the suffering of residential school students in 2009, in a way that did not imply the Church's responsibility. There is hope that Pope Francis might visit Canada in 2018, meet with residential school survivors, and offer an apology. has a Canadian Catholic Aboriginal Council.

- In the United Church of Canada, there is an Aboriginal Ministries Circle. It apologized for its participation in colonialism in 1986, and for its involvement in residential schools in 1998. It runs an Aboriginal centre for spirituality and training for ministry in Manitoba.

- Native Pentecostal churches have developed, including in Vancouver and Chilliwack.

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada supports initiatives for justice for Indigenous peoples.

- The Presbyterian Church in Canada supports ministries with Aboriginal persons. Its General Assembly published a confession in 1994 which asked forgiveness from Indigenous persons for its role in residential schools.

Stories

The Ojibway writer Richard Wagamese (shown at right), in "Returning to Harmony," speaks of how he was affected by the residential school system, and how he was able to reach a sense of reconciliation.

A gathering of Aboriginal Christians in 2006, many of them with experiences in Canadian prisons, discussed the diversity of Christian experiences and the diversity of ways in which these might be connected with Indigenous spiritualities.