Christianity and multiculturalism in Canada since 1960

WYH3271HS Winter 2017 March 16, 2017

Links

CBC television has this recent (March 2017) video on racism, "The Skin We're In".

A video on the oldest Korean church in Toronto (1967).

The story of Avenue Community Church, a Korean church.

A CBC-TV report of 2013 on ethnic diversity in the Roman Catholic Church.

A DMin thesis on cultural diversity in an Anglican setting (pdf) by Sonia Hinds.

Canada's founding myth

The government of Canada citizenship guide identifies three founding peoples: Indigenous, British, French. This view is no doubt shared by many Canadians, and has been a popular interpretive lens for understanding the history of Canada and for defining a national Canadian spirit. It helps explain why English and French are, federally, the two official languages of the country, and why Aboriginal rights are recognized in the Canadian Constitution, section 35.

For the historian it qualifies as a mythical metanarrative, downplaying historical conflicts in the interest of pacifying social and political discontent. In fact, —

- Indigenous peoples were in Canada long before the French or the British, and had no intention to found a nation. When the French and British came, Indigenous peoples did not participate with them politically or share in civil rights;

- British Canadians often looked down on French Canadians as a conquered people, given to papistry, and of somewhat inferior national character;

- French Canadians have often fought, and continue to fight, to separate from "the rest of Canada" in order become who they are truly meant to be. .

The 'founding myth' functioned for many years to justify a whites-only immigration policy and a frankly racist understanding of Canadian identity.

The 'founding myth' functioned for many years to justify a whites-only immigration policy and a frankly racist understanding of Canadian identity.

Bigotries

Until the late nineteenth century Canadian immigration was largely restricted to persons from the British Isles, northern Europe, and the United States.

The settlement of western Canada, and the removal of Indigenous peoples to reserves, required large-scale immigration. Sir Clifford Sifton (1861–1929), the cabinet minister in charge of immigration from 1896 to 1905, crafted an immigration policy which favoured British and white American immigration, but was forced by economic circumstance and practicality to allow other ethnicities. Over the next decades government regulations defined preferred catgories (those most easily assimilated into a white British Protestant or French Roman Catholic culture), non-preferred (generally eastern and southern Europeans), and unacceptable (Jews and visible minorities).

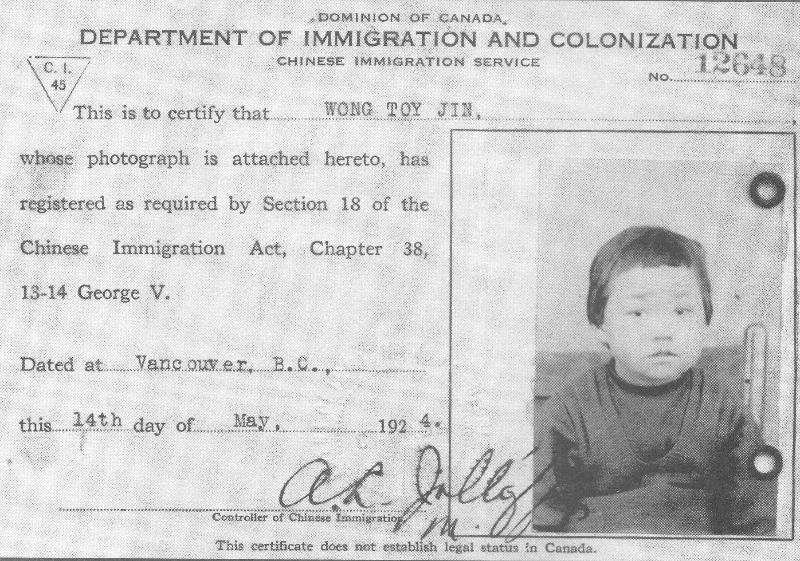

Among the instruments for the exclusion of visible minorities were the Chinese Exclusion Act (1923) and the Continuous Journey Regulations (1908) which excluded people from Japan and India. People of African descent were excluded through a number of means, including health regulations (on the grounds that they wouldn't be able to acclimatize to Canada's cold climate), diplomatic agreements, head taxes, and bureaucratic obstruction.

Mainline Protestant denominations — United, Anglican, Presbyterian —overwhelmingly favoured a British (and, as necessary, a French) Canada, and until World War II lobbied insistently against open immigration.

After World War II

Refugees. Canada began establishing refugee policies after World War II. Jews had been largely excluded from Canada through the 1930s, but with revelations of the horrors  of the Holocaust, refugee Jews began to be admitted in 1945. Other provisions for block groups followed (e.g., Hungarians, Czechoslovakians, Ugandans).

of the Holocaust, refugee Jews began to be admitted in 1945. Other provisions for block groups followed (e.g., Hungarians, Czechoslovakians, Ugandans).

Shame. The Viola Desmond case in 1946 received nationwide publicity, and is often seen as beginning the civil rights movement in Canada. Desmond, a black businesswoman, seated herself in a whites-only section of a movie theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, and was arrested. Her church, Cornwallist Street Baptist Church in Halifax, encouraged her to fight the charge, and supported her through the trials, judicial reviews, and appeals. She was convicted, but the nationwide publicity shamed the nation, and Christian and other leaders advocated for the equal and nondiscriminatory treatment of visible minorities.

Desmond was pardoned, posthumoulsy, in 2010. In 2018 her likeness will appear on the Canadian $10 bill.

Family reunification. Humanitarian concerns promoted provisions for immigration for the purpose of family reunification.

Economic necessity. Immigration was seen as necessry to support the growing post-War economy.

The origins of multiculturalism

Ellen Fairclough (1905–2004)

Ellen Fairclough (1905–2004)

Fairclough, who was raised in Zion Tabernacle Methodist Church (now Zion United Church), Hamilton, was Immigration Ministry from 1958 1962, in John Diefenbaker's Conservative government. (She was the first woman cabinet minister in Canada. She was also the first woman prime minister in Canada, serving as acting prime minister for a day in Diefenbaker's absence.)

She introduced regulations that largely eliminated racial discrimination in immigration. She also increased immigration limits, and liberalized refugee policy.

Beginning in 1971, and in every year since, most immigrants to Canada are of non-European ancestry.

The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism

This royal commission was established by Lester Pearson's Liberal government in 1963, in response to grievances from French Canadians in the context of the Quiet Revolution.

Its Preliminary Report, published in 1965, recommended a bicultural Canada; it was attacked both by "One Canada" Conservatives and by "Third Force" Canadians (neither British nor French).

Its Final Report, published in 1969, led to the Official Languages Act of 1969, making English and French the official languages of Canada. It also recommended greater status and support for persons of other cultures.

Multiculturalism

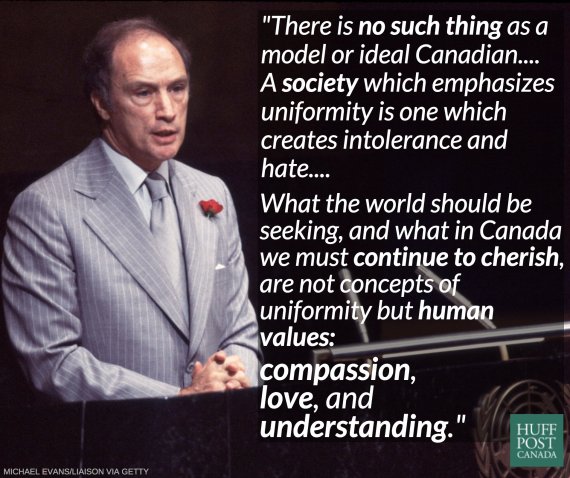

In 1971 Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau announced in the House of Commons a policy of multiculturalism. He declared that the government of Canada accepted "the contention of other cultural communities that they, too, are essential elements in Canada." Part of the political calculus in the announcement was to shore up Liberal support in western Canada, where many Third Force Canadians lived, and to check the separatist cause in Quebec, which saw biculturalism as an acknowledgement of the special and distinct status of Quebec within Confederation — a view which Trudeau deplored.

Ethnodiversity in Canada today

Post-Nationalism

In an interview with the New York Times in December 2015, a few weeks after his election, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called Canada "the first postnational state." Canada is characterized by a multiplicity of identities from all over the world. There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada"....There are shared values — openness, respect, compassion, willingness to work hard, to be there for each other, to search for equality and justice."

Immigration and ethnic identities

Based on the last full census in 2011, Statistics Canada has published an overview of immigration and ethnocultural diversity in Canada. Canada's foreign-born population was over 20% of its total population, the highest of the G8 countries. Asia was the largest source of immigrants. More than 200 ethnic groups were reported. Just under 20% of the population identified themselves as visible minorities; of these, the three largest groups were South Asians, Chinese, and Blacks. Most lived in the three largest census metropolitan areas (Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver).

About 67% of respondents reported affiliation with a Christian denomination. Other religions reported were:

- Muslim, 3.2%

- Hindu, 1.5%

- Sikh, 1.4%

- Buddhist, 1.1%

- Jewish, 1.0%

- No religious affiliation, 23.9%

Christianity and multiculturalism in Canada

Bramadat and Seljak

This subject has begun to be researched in the last few years. An early example is Paul Bramadat and David Seljak, eds., Christianity and ethnicity in Canada (Toronto ; Buffalo : University of Toronto Press, 2008). U of T library users can access it here, This is a collection of essays by various scholars, each looking at ethnicity in a particular Christian denomination or tradition. The editors state their major points in their Introduction:

- They affirm "secularization" in Canada, but they seem to use the term in the sense of the disentanglement of Christianity from major state institutions.

- Religion in Canada has been privatized and subjectified, loosening community bonds. Older Christians, across different denominations, report a sense of "loss".

- Christianities are traditionally related to ethnicity: English Anglicans, Scottish Presbyterians, German or Scandinavian Lutherans, Greek Orthodox, Ukrainian Catholic, Dutch Reformed, Frisian Mennonite, etc.

- Many Canadians think of themselves as Christians, often for reasons related to their ethnicity, but have an extremely loose connection with any church institution. The borrow the phrase "believing without belonging."

- Nevertheless, Canadians who think of themselves as Christians but don't practice Christianity shouldn't be thought of as fooling themselves. They are negotiating complex identities.

- Many of these religious traditions are becoming ethnically diverse: Nigerian Anglicans, Korean Presbyterians, Chinese United Church, etc. This has created tensions, partly because immigrant Christians are often more conservative on sexual and social issues than Christians of the dominant ethnicities. A tendency is the erosion of ethnic correlations to Christian traditions; thus, German-speaking services among Lutherans have become rarer than they once were.

- The case of Quebec is peculiar; it is a secular province but the impact of the Roman Catholic ethos survives.

- Evangelical congregations are sometimes ethncially particular, but in most cases are reportedly welcoming to all.