The "Quiet Revolution" in Quebec

WYH3271HS Winter 2017 January 19, 2017

Links

On the asbestos strike, a recent book is Malouf and Deslile, Le quatuor Asebestos

On the Church's acquiescence in the Quiet Revolution, see David Seljak, “Why the Quiet Revolution was ‘Quiet’: The Catholic Church’s Reaction to the Secularization of Nationalism in Quebec after 1960,” Canadian Catholic Historical Association Historical Studies 62 (1996): 109–124.

On the Quiet Revolution, see Wikipedia.

The "Quiet Revolution" ("la Révolution tranquille")

The “Quiet Revolution” (la révolution tranquille) in Quebec in the years after 1960 is seen as transforming the province from a Catholic society to a secular one. There are three major dimensions of this transformation.

- ‘Secularization’ can mean that social authority and resources move from the church to the state.

- In 1960 most of Quebec’s schools and francophone universities, hospitals, and social services were administered by the Church; by 1970, most were administered by the state.

- ‘Secularization’ can also mean that religion becomes less important in society.

- A metric of this transformation in Quebec is the rapid decrease in regular church attendance during this period. Thus, in 1958, 75% of the population attended mass every Sunday (Reginald Bibby, Unknown Gods, p. 6); in 1975 the proportion was down to 31% (Bibby, “Religion a la Carte in Quebec,” 2007.

- However, not everyone agrees that ‘secularization’ in this sense actually happened. Michael Gauvreau, The Catholic Origins of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, 1931–1970 (McGill-Queen’s, 2005) has argued that during the Quiet Revolution Catholics didn’t generally leave Catholicism but, simultaneously with Vatican II, expressed their Catholicism in new ways: less clericalistic, more focused on social justice, more ecumenical, less anxious about modernity. Writing in 2007, Reginald Bibby found that 83% of Quebec’s population continued to identify themselves as Roman Catholic, despite dramatically decreasing attendance. Jacques Rouillard, a historian at l'Université de Montréal, argues that the Quiet Revolution was a natural evolution in Quebec history. (The link is pdf.)

- 'Secularization' can reorient ideas and movements, and Quebec nationalism moved from a religiously coloured sense of the distinctive vocation of Catholic French Canada to a more politically oriented sense of la société Québecoise, connected with aspirations to self-determination and, frequently, constitutional separation from the rest of Canada.

Before the Quiet Revolution

Quebec was among the world’s most Catholic societies. Its beautiful church buildings in central locations were packed with people on Sundays. There were tens of thousands of priests and members of religious orders. The Church had wealth, prestige, close ties to Rome, and well respected leaders. It was a force for social unity in Quebec.

The Quebec style of Catholicism was distinctly ultramontane. Its ultramontanism was expressed in its devotion to the papacy, its triumphalistic tone, its clericalism, its favour for a monopolistic Catholic state, and its mission to reconquer lost spiritual territory.

Education, health, social services, labour, media

Before the 1960s, almost all francophone Quebeckers were Roman Catholic, and Quebec was seen as a Catholic society. The Church, not the state, oversaw most educational and social services.

- Primary and secondary education. The British North America Act of 1867, which confederated Canada, preserved the Roman Catholic confessional school system of Quebec. From 1875 to 1964, schools were administered by a Department of Public Instruction, which had a Catholic committee and a Protestant committee. By the time of the Quiet Revolution, there were about 1500 Catholic school boards each setting its own curriculum. They typically depended on Roman Catholic clergy or members of religious orders for a large proportion of their teaching resources. Teachers were trained by religious orders or in normal schools.

- Higher education. The Roman Catholic Church, either through diocesan judicatories or religious orders, administered about a hundred collèges classiques. (About twenty admitted women.) The three francophone universities, Laval, Montréal, and Sherbrooke, had

Roman Catholic charters. By 1960 only 11% of francophone Quebeckers finished grade eleven, and only about 3% of French Canadians aged 20 to 24 attended university.

Roman Catholic charters. By 1960 only 11% of francophone Quebeckers finished grade eleven, and only about 3% of French Canadians aged 20 to 24 attended university. - Medical care. Roman Catholic religious orders ran most hospitals in Quebec, controlled the education of francophone nurses, and played a major role in medical care. The first lay francophone day nurses appeared in the 1940s, but the great majority of nurses continued to be women religious.

- Social services. The Roman Catholic Church dominated welfare services, family services, charitable institutions such as orphanages (the ‘orphans’ were often children born out of wedlock), and youth associations. In many cases the institutions received some funding from provincial or federal government sources.

- A particular instance which has received particular attention in the press is that in 1955 some orphanages were transformed into mental hospitals, which received higher government funding, and thousands of orphans were certified as mentally defective in order to transfer them to these more lucrative institutional settings. Many reported being victimized by physical and sexual abuse, and medical experimentation.

- Labour. Under the influence of the encyclical rerum novarum (1891), the Roman Catholic Church permitted ‘workingmen’s unions’ so long as they were clearly Catholic, and not secular or ecumenical. It also supported farmers’ cooperatives and credit unions for workers. The Church hierarchy was, however, resolutely anti-socialist. Cardinal Villeneuve of Quebec spoke out forcefully int he 1930s against the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, the precursor to the New Democratic Party.

- Media. The Catholic Church published books, newspapers, and journals, and produced films and programs for radio and television.

The state

Maurice Duplessis (1899–1959), called "le Chef," was premier of Quebec from 1936 to 1939, and from 1944 to 1959. His party, the Union Nationale, was immensely popular in rural and small-town Quebec, and it expressed and promoted conservative, Catholic, family-based values. Duplessis was a committed Roman Catholic who enjoyed warm relationships at the Vatican. Duplessis's government had an anti-statist outlook and took few economic initiatives, but it supported capitalist ventures from outside. In particular, it welcomed American corporations that wanted to exploit the province's natural resources.

Duplessis is often seen as promoting xenophobic, repressive, and anti-Semitic policies, and many refer to his reign as la grande noirceur (‘the great darkness’). As with all historical interpretations, not all agree that there was a grande noirceur, since Quebec also had its flourishing urban, industrial, and progressive subcultures as well. One of Duplessis' most ardent admirers is the conservative financier, columnist, amateur historian, and convicted felon Conrad Black, whose positive assessment of Duplessis can be read here,

The Church

The late distinguished Quebec intellectual Claude Ryan (1925–2004) has helpfully identified two dimensions to the Church before the Quiet Revolution:

- On the one hand, it was the religious dimension of almost the entire society, and therefore had a stake in maintaining the social order. Its leaders were on good terms with the leaders of the state. Policies were often developed through negotiations between government leaders and Church leaders.

- On the other hand, for the same reason, the Church was closely identified with "the people". Ryan recalls a conversation with a bishop of Sherbrooke who noted that almost all the revenues of the diocese came from ordinary people leading hardscrabble lives; its roots were there, not in American capitalism. Where the interests of the government diverged from the interests of the working class, the Church might well identify with the people. This would become clear in the asebestos strike of 1949.

A significant feature of Catholic Church life from the 1920s on was Catholic Action. Catholic action groups were lay organizations, under a bishop’s mandate. These had developed in Europe in the nineteenth century, but were aggressively promoted by Pope Pius XI, "the Pope of Catholic Action". They were instruments for the moral and spiritual formation of the laity, and, in the words of Pope Pius XI in 1927, they represented the participation of the laity in the apostolate of the hierarchy. In Quebec there were Catholic Action groups for farmers, workers, women, and students, among others.

Precursors of the Quiet Revolution

Post-war boom

Many historians think that a post-war economic boom in Quebec brought to prominence a new university-educated bourgeoisie that embraced modern urban commercial and industrial values.

The asbestos strike

Quebec produced 85% of the world’s asbestos, and the major corporation in the town of Asbestos, Quebec, was Johns Manville. In February 1949, five thousand asbestos workers went on strike, seeking, among other objectives, $1 an hour in wages and attention to health concerns such as silicosis. The company brought in scab labour and endeavoured to starve the workers into submission; Duplessis’ government declared the strike illegal and sent in the provincial police, whose conduct earned them an international reputation for brutality. The police made mass arrests, and raided the parish church.

In general the Church supported the workers, who were members of the Canadian Catholic Confederation of Labour. Most conspicuous in his support was Joseph Charbonneau (1892 -1959 ), the archbishop of Montreal, reportedly the largest Catholic diocese in the British Empire. He had every parish in his archdiocese raise collections to help the workers and their families. His public statements were crystal clear:

“The working class is the victim of a conspiracy aimed at crushing them,” he preached at a mass in his cathedral. “When there is a conspiracy to crush the working class, it is the Church's duty to intervene. We value people more than capital."

The strike was settled as of July 1, after mediation by the archbishop of Quebec. The workers gained little of what they had demanded, and many workers never regained their jobs. It has been identified as the first organized populist opposition to the Duplessis government. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, in the book The Asbestos Strike (1974), interpreted the strike as the beginning of modern Quebec.

Archbishop Charbonneau resigned abruptly in February 1950… It has long been speculated that his resignation was forced by the Vatican under pressure from Duplessis, although many other Church leaders in Quebec also supported the workers. He was replaced by Paul-Émile Léger.

Paul-Emile Leger

Before being appointed archbishop of Quebec in March 1950, Leger moved among conservative circles at the Vatican, and it was expected that he might be more favourable than Charbonneau had been to Duplessis' conservative, anti-statist, status quo ideologies. However, Léger would prove to be even more progressive, and arguably more effective, than Charbonneau. At Vatican II his was a progressive but orthodox voice. In Canada he was a strong ecumenist. In Quebec he recruited lay leaders, supported workers, and recognized value in the new nationalism. He resigned in 1968 to work in a leper colony in Cameroon.

The anti-Duplessis media

Le Devoir. Under the editorship of Gerard Filion (1947-1963), this independent daily newspaper took a critical view of the Duplessis government, supported workers, and critiqued Catholic clericalism. Gerard Pelletier wrote for Le Devoir from 1947 to 1950.

Radio Canada. This publicly supported radio and television corporation showcased progressive media commentators such as Rene Levesque.

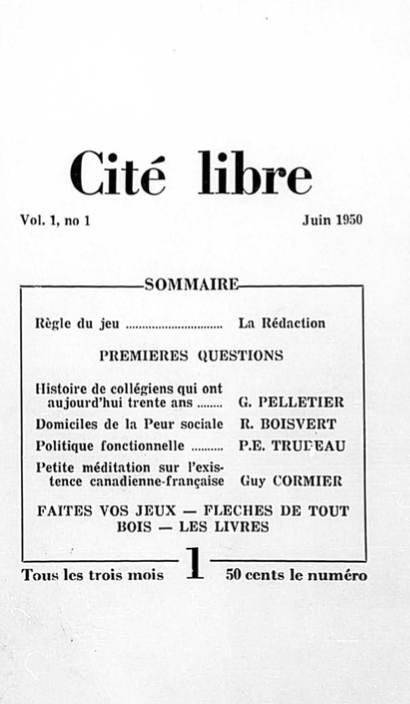

Cite Libre. After the asbestos strike, Pierre Elliott Trudeau was moved to helped found the progressive Quebec journal Cite Libre. , one of the few Quebec periodicals which dared to be forthrightly opposed to the Duplessis regime.

Les trois colombes (Anglophones called them "the three wise men"). Trudeau, Pelletier, and Jean Marchand, who had roused the workers at the asbestos strike with his spellbinding speeches, became a significant progressive triumvirate in the 1960s.

Les insolences du frère Unsel

This book, published anonymously in 1960, was a scathing attack on the Catholic educational system. Its author was later disclosed to be Jean-Paul Desbiens (1927-2006), a member of the Marist order. With dry wit, the work pictured an antiquated and repressive Catholic educational system that was at base anti-intellectual and culturally impoverished. It quickly sold 100,000 copies, ten times as many as a typical best-seller in Quebec. It can be read (in French) here.

The Quiet Revolution begins

The trigger

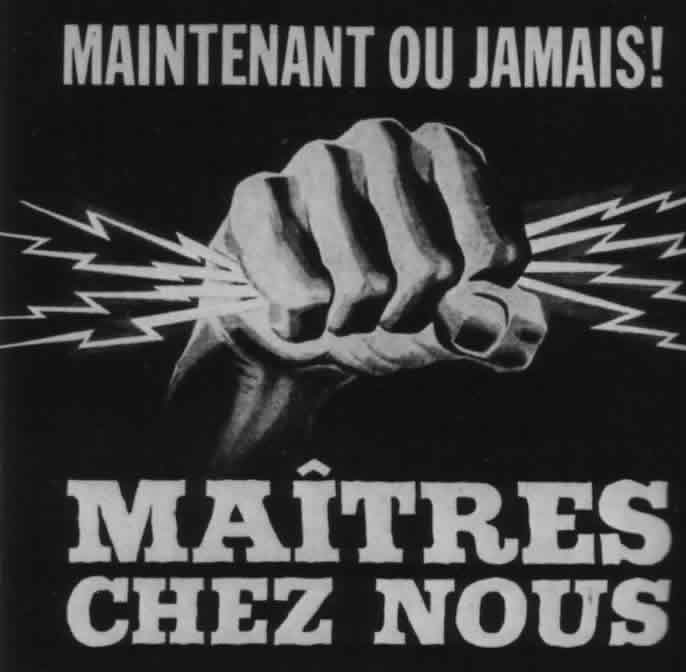

The acknowledged trigger of the Quiet Revolution of Maurice Duplessis in 1959; his successor (Paul Sauvé) died a few months later; and in an election of 1960, the Liberal Party of Quebec was elected to power under its premier Jean Lesage (1912–1980). The party’s campaign slogan “maîtres chez nous” expressed French Canadians’ revolt against American and English Canadian economic dominance. It also implied that voters could gain control of their lives by electing a government that would stand up for workers, not capitalists; it thus reflected a desire to move from a nationalism centred on a strong Church, to a nationalism centred on a strong state. “Maîtres chez nous” became a rallying cry of Quebec nationalism.

Changes during the Quiet Revolution

- Health care and social services. Quebec joined the federal hospital insurance program in 1961. The government established a study committee on public assistance (the Boucher Committee, 1963) and accepted its recommendations for much increased state intervention in order to promote greater social equality. The training of nurses was secularized. Movements towards overhauling and secularizing the medical system resulted in the Health Insurance Act of 1970, a comprehensive measure for the prevention and treatment of health problems and the improvement of social conditions. The Quebec Pension Plan was created. The Civil Code was changed in 1964 to provide for the legal equality of spouses.

- Education. In 1963 the government appointed a royal commission on education, respectfully appointing a senior Roman Catholic priest, Msgr Alphone-Marie Parent, as chair. In 1964 the government created a Ministry of Education. It maintained a confessional system of primary and secondary education (as required in the BNA Act), but reduced the nu

mber of Roman Catholic school boards from 1500 to 55, and standardized curriculums. It abolished the collèges classiques and replaced them with secularized CÉGEP’s (collèges d’enseignement général et professionel) offering two-year pre-university and three-year vocational programs. The Universités Laval, Montréal, and Sherbooke all received secular charters, and the Université du Québec system was established. Educational access was improved. Normal schools were abolished, and teachers are now trained in university programs. [Note. In 1997 school boards were secularized; confessional streams were replaced by linguistic streams.]

mber of Roman Catholic school boards from 1500 to 55, and standardized curriculums. It abolished the collèges classiques and replaced them with secularized CÉGEP’s (collèges d’enseignement général et professionel) offering two-year pre-university and three-year vocational programs. The Universités Laval, Montréal, and Sherbooke all received secular charters, and the Université du Québec system was established. Educational access was improved. Normal schools were abolished, and teachers are now trained in university programs. [Note. In 1997 school boards were secularized; confessional streams were replaced by linguistic streams.] - Labour. The Catholic workingmen's unions secularized. La Confédération des travailleurs catholiques became la Confédération des syndicats nationaux. Similarly, l'Union catholique des cultivateurs became l'Union des producteurs agricoles. The government allowed the unionization of the civil service A new labour code (Code du Travail) was adopted in 1964, which made unionizing much easier and gave public employees the right to strike.

- Nationalizations. The government's agency Hydro-Québec bought out almost all the private distributors of electricity in the province in 1963, and began planning major projects. Several public companies were created to exploit the natural resources of the province: SIDBEC (sidérugie du Québec) for iron and steel, SOQUEM (société québecoise d'exploration minière) for mining, REXFOR (la Société de recupération, d'exploitation et de developmment forestière) for forestry, and SOQUIP (la Société québecoise d'initiatives petrolieres) for oil and petroleum.

Vatican II

Vatican II met from 1962 to 1965, simultaneously with the Quiet Revolution. It was hugely influential in helping Roman Catholic leaders and intellectuals in Quebec discern a direction for re-visioning the Church in its new social and political context. Iin particular, Vatican II:

- Rejected the kind of state establishment of religion where governments support a religious monopoly;

- Recognized a significant role for the apostolate of the laity, and restrained clericalism;

- Accepted the modern world;

- Affirmed the Church's commitment to social justice.

The Church in Quebec in the Quiet Revolution

Predictably, some Catholics supported the changes, and some opposed them. Dominicans, for instance, were notable for supporting the new order, while Sulpicians more conspicuously resisted.

But perhaps surprisingly, the Church and the new political order adapted to each other. The progressives generally continued to consider themselves Catholic, though in this age of Vatican II their Catholic identity shifted. For their part, the bishops affirmed the people's right to self-determination, and rejected the old idea that the proper task of the state was to favour the Catholic Church.

Claude Ryan has noted the following themes in the pastoral letters of the Quebec bishops on social and economic matters between 1960 and 1980:

- Economic progress should be harmonized with social justice and human development.

- Christians should be supcisious of both Marxist ideology nor capitalist ideology

- The Church identifies with the poor, the weak, the marginazlied, immigrants, the unemployed, the homeless

- Christians affir human rights

- Organizations following a cooperative philosophy are to be preferred

He notes that the tone of the pastoral letters are no longer authoritative but reflective. The bishops are no longer negotiating policies with the government from a position of power and moral authority, but discussing the implications of Christian discipleship with the people.