The Toronto School of Theology

WYH3271HS Winter 2017 January 26, 2017

Links

Wikipedia articles

On the early days of St. Michael's

See Mark George McGowan, Catholics at the Gathering Place: Historical Essays on the Archdiocese of Toronto, 1841-1991 (Dundurn, 1993).

Francis Boland, C.S.B., "Father Soulerin, C.S.B., Founder and Administrator," 1956

L. Shook, "St. Michael's College: The Formative Years, 1850–1853," 1950.

Robert J. Scollard,Dictionary of Basilian Biography,2nd ed. revised by P. Wallace Pratt (University of Toronto Press for the Congregation of St. Basil, 2005)

On the early days of Wycliffe

Alan L. Hayes, "The Struggle for the Rights of the Laity in the Diocese of Toronto 1850–1879," Journal of the Canadian Church Historical Society 26 (1984): 5–17. U of T users can access this here.

On the early days of Knox

Brian J. Fraser. Church, College, and Clergy: A History of Theological Education at Knox College, Toronto, 1844-1994. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995.

Richard W. Vaudry, "Theology and education in early Victorian Canada: Knox College, Toronto, 1844-61," Studies in Religion 16 (1987): 431–447.

On the early days of Emmanuel

Kenneth H. Cousland, The Founding of Emmanuel College of Victoria University in the University of Toronto, Toronto? 1978. Available at the Emmanuel College library.

St. Michael's, topics

Alexander Reford, "St. Michael's College at the University of Toronto, 1958–1978: The Frustrations of Federation," 1995.

Kevin J. Kirley, "A Seminary Rector in English Canada During and After Vatican II," 1976.

A brief overview of TST

TST is a consortium of seven member theological colleges at the University of Toronto:

- Emmanuel College, a theological college within Victoria University. Emmanuel is connected to the United Church of Canada. Emmanuel is located adjacent to the east entrance of the Museum subway station.

- Knox College, of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. It's located in King's College Circle, at the heart of U of T.

- Regis College, named for Christ the King (collegium Christi Regis), a Roman Catholic school connected to the Society of Jesus. It's in the old Christie Mansion at the corner of Queen's Park Crescent East and Wellesley Street.

- St. Augustine's Seminary, the major seminary of the Roman Catholic archdiocese of Toronto. It's located on the Scarborough Bluffs.

- St. Michael's College, more formally known as the Faculty of Theology of the University of St. Michael's College, a Roman Catholic school connected with the Congregation of St. Basil, a small teaching order that originated in France in 1822. The

main St. Michael's campus is roughly defined by Queen's Park Crescent East, St. Mary Street, Bay Street, and both sides of St. Joseph Street.

main St. Michael's campus is roughly defined by Queen's Park Crescent East, St. Mary Street, Bay Street, and both sides of St. Joseph Street. - Trinity College, more formally known as the Faculty of Divinity in the University of Trinity College, connected with the Anglican Church of Canada. It's located on the north side of Hoskin Avenue at Queen's Park Crescent West.

- Wycliffe College, connected with the Anglican Church of Canada, and representing an evangelical theological position. It's on Hoskin Avenue across from Trinity College.

Six of the seven colleges are located within a ten minutes' walk of one another.

The University of St. Michael's College, the University of Trinity College, and Victoria University are, by Acts of the provincial legislature, federated universities of the University of Toronto. Knox and Wycliffe are federated colleges of the University of Toronto, also by provincial statute. Regis and St. Augustine's are affiliated with the University of Toronto by mutual agreement.

"Toronto School of Theology" can describe the consortium, but it can also describe the not-for-profit corporation which provides various administrative services for the consortium. The TST corporation is not chartered as an educational institution; it registers no students; and it grants no degrees. It provides some common registrarial services and common financial services, and acts as a liaison for various purposes, notably educational quality assurance, between the member colleges and the University of Toronto. The TST building, on the St. Michael's campus, is located on the corner of Queen's Park Crescent East and St. Joseph Street.

All of TST's degree programs operate at a post-baccalaureate level and are accredited by the Association of Theological Schools of the United States and Canada. First theology degrees are called basic degrees, and include the Master of Divinity, Master of Theological Studies, Master of Pastoral Studies, Master of Sacred Music, Master of Religious Education, and Master of Arts in Ministry and Spirituality. Graduate or advanced theology degrees include the Master of Arts, Master of Theology, Doctor of Theology, Ph.D., and Doctor of Ministry.

TST's website is at www.tst.edu.

TST has three affiliate schools: Conrad Grebel (Mennonite) in Waterloo; Huron (Anglican) in London; and Institute for Christian Studies (Christian Reformed) in Toronto. It has had a long-time friendly relationship with Waterloo Lutheran.

Origins: a historical summary

King’s College (1827): predecessor of the University of Toronto

King’s College began its legal existence in 1827 when it received a royal charter. It was the project of the Reverend John Strachan (1778–1867), the parish priest of York (now Toronto), who was a key figure in the oligarchy that controlled the colony of Upper Canada (now Ontario). This oligarchical group has been called “the Family Compact” because of their  web of relationships by marriage. (For instance, John Strachan's son married the daughter of the Chief Justice.) King's College was controversial because, through Strachan's artful advocacy, it was to be an Anglican school benefiting from a munificent landed endowment from the Crown. It was also, at the time, the only public university on the horizon, giving Anglicans a monopoly on the higher education of the colony. Public controversy and other problems delayed the opening of King’s College to 1843. Its building occupied the site of what is now the provincial legislature in Queen’s Park.

web of relationships by marriage. (For instance, John Strachan's son married the daughter of the Chief Justice.) King's College was controversial because, through Strachan's artful advocacy, it was to be an Anglican school benefiting from a munificent landed endowment from the Crown. It was also, at the time, the only public university on the horizon, giving Anglicans a monopoly on the higher education of the colony. Public controversy and other problems delayed the opening of King’s College to 1843. Its building occupied the site of what is now the provincial legislature in Queen’s Park.

Resentments of Anglican privilege in this and other respects continued to build. When ‘responsible government’ was granted in 1848, the elected representatives of the people were finally able to effect change. In 1849, the reformer Robert Baldwin submitted a bill, which was successfully passed and proclaimed, to take away the endowment of King’s and apply it to a new non-sectarian public university, "the provincial university," the University of Toronto. This legislation is called the Baldwin Act or the University of Toronto Act. (Baldwin was himself an Anglican, and was regarded by Strachan as a traitor to the Church.) Against the background of a generation of religious conflict about higher education in the colony, the Baldwin Act prohibited lectureships and degrees in divinity at the University of Toronto. And through many revisions of the University of Toronto Act, this provision remained in force until 1978.

Victoria University (1841)

The Upper Canada Academy was established as a coeducational preparatory school in Cobourg in 1832 by the Canada Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. One of its founders was Egerton Ryerson (1803–1882), a Methodist minister who had become celebrated in Upper Canada by his forthright opposition to Strachan and the Family Compact. When the colonial government resisted chartering the Academy, the Methodists went over its head to Great Britain, and secured a royal charter in 1836. Ryerson served as president. In 1841 it was elevated to the status of a college (which barred females from attending), and it was incorporated as Victoria College, in honour of the Queen. It granted the first BA in Canada West in 1845.

honour of the Queen. It granted the first BA in Canada West in 1845.

The first college buildilng (pictured at right) still stands at 100 University Street East in Cobourg, and is used as a retirement residence.

Victoria created a Faculty of Theology in 1871, to train students for the ministry of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. In 1884, after the Wesleyan Methodist and Methodist Episcopal Churches merged, Victoria and Albert University in Belleville, which was the ME school, merged as well; Victoria College became Victoria University, and the two faculties of theology came together. .

Knox College (1844)

Queen’s College had been founded in Kingston in 1841 as an educational institution of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection of the Church of Scotland. A schism led by Scottish evangelicals in 1843, called the Disruption, which created the Free Church of Scotland, triggered a similar schism in Canada, called the Free Church of Scotland Canada Synod. Knox College was founded in Toronto by a sizable Free Church of Scotland group that seceded from Queen’s. Various groupings of Presbyterian churches reunited in a complex process extending from 1860 to 1875, when the Presbyterian Church in Canada was organized. Knox is its largest theological school.

The Diocesan Theological Institute, Cobourg (1842)

The diocese of Toronto was created for the Church of England in Canada in 1839. In 1842 the first bishop, John Strachan, established an institution in Cobourg for the training of clergy, under the tutelage of the rector of St. Peter’s Church, Cobourg.

Trinity College (1851)

John Strachan (pictured at right), disgusted with the secularization of King’s in 1849, was undaunted. He sailed to England and raised funds for a new Anglican university, called Trinity. This incorporated the Diocesan Theological Institute as its Faculty of Divinity. In 1852 it was opened on Queen Street West, on the site of what is now Trinity-Bellwoods Park. For its first few decades it stood opposed to the ostensibly secular, ecumenical educational ethos of the University of Toronto. It was closely linked to the Anglican diocese of Toronto; its provost from 1851 to 1881, George Whitaker, was also for a while the archdeacon of the diocese. The early history of Trinity is very engagingly told by William Westfall,The Founding Moment(McGill-Queen's University Press, 2002).

St. Michael’s College (1852)

In 1852 the Roman Catholic archbishop of Toronto, A.-F.-M. de Charbonnel, began organizing a minor seminary leading students towards the priesthood, and a classical college leading students towards a secular career. Originally separate, they came together as St. Michael’s College, under the management of a small French teaching order, the Congregation of St. Basil. Connecting a minor seminary so closely with a classical college was irregular and caused some consternation at high ecclesiastical levels, since aspirants to Holy Orders were supposed to be educated apart from worldly influences, but teaching resources were too limited to support separate streams.

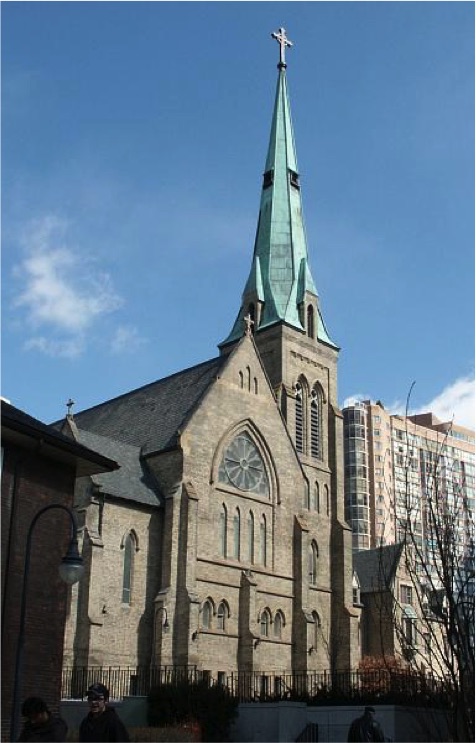

Land was given for St. Michael's by John and Charlotte Elmsley; John was an entrepreneur and philanthrophist. Scandalously, he had been raised as an Anglican in the "Family Compact" but had converted to his wife’s Roman Catholicism in 1833. As it happens, his parents, Chief Justice John and Mary Elmsley, had sold family land to King’s College in 1829, which explains why the St. Michael’s campus is directly adjacent to the University of Toronto campus. The proximity of these two campuses would one day be a significant factor in promoting t he interchange that has been so vital to University federation in Toronto, and to the Toronto School of Theology. Pictured at left: St. Basil's Church, the oldest building on the U of T campus, located on the land gifted by the Elmsleys, and still pastored today by the Congregation of St. Basil. .

he interchange that has been so vital to University federation in Toronto, and to the Toronto School of Theology. Pictured at left: St. Basil's Church, the oldest building on the U of T campus, located on the land gifted by the Elmsleys, and still pastored today by the Congregation of St. Basil. .

For many years, St. Michael's students who were training for the priesthood either finished their formation at a major seminary, or were mentored locally one-on-one by senior priests. To address this situation, in 1892 the Basilians opened a novitiate in Toronto. In 1902 they established a scholasticate for the novices, that is, a house where they could study philosophy or theology with a view to ordination. In 1937 St. Basil’s Scholasticate was renamed St Basil’s Seminary.

In 1954, in order to qualify for government funding, St. Michael's created a Faculty of Theology in which the seminarians could take courses leading to an academic civil degree (the Bachelor of Sacred Theology or S.T.B.).

By the 1960s St. Michael's could justly be considered the premier institution of Catholic theological studies in English Canada, perhaps in rivalry with the University of Ottawa. Its Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, founded in 1929 by the eminent Étienne Gilson, and receiving pontifical status in 1939, enjoyed global prestige. Its theological faculty was academically strong and active. Recognizing the appeal of its theological programs not just to prospective clergy and religious but to laypeople as well, in 1962 it began an M.A. program in theology, and in 1964 a Ph.D. program. Its Faculty of Theology now had two divisions, "professional" for seminarians and "graduate" or "academic" for laypeople.

Wycliffe College (1877)

Wycliffe was founded in 1877 under the name Protestant Episcopal Divinity School, predominantly by lay Anglicans in the diocese of Toronto who challenged their church leaders for being clericalistic, insufficiently respectful of the English Reformation, and anti-ecumenical. This was a local case of a long course of sometimes bitter disputes across the Anglican communion, from about the 1840s to the 1890s, over what was called ‘churchmanship.’ These disputes pitted ‘high-church’ advocates of episcopal authority and a high view of sacramental grace and ecclesiastical tradition, against ‘low-church’ advocates of lay leadership, the centrality of preaching, and the theological authority of ‘Scripture alone’. In Toronto, Anglicans were also divided in their attitude towards the University of Toronto. Low-church Anglicans supported it, and sent their sons there; high-church Anglicans steered clear of it, and sent their sons to Trinity instead.

Some think that other factors were in play as well. It looks as if the Anglican diocesan establishment was primarily English and Scottish in heritage, and Tory in politics, while many of the most prominent lay leaders were Irish in heritage, and Liberal in politics. The lay leader who was most influential in founding Wycliffe was Samuel Hume Blake (1835–1914), a proud Irish Canadian and Liberal Party stalwart (his brother Edward was the provincial Liberal leader for many years).

University federation (1887)

The University of Toronto struggled in its early years. Many parents preferred their children to go to denominational schools such as Victoria, St. Michael’s, Trinity, or Queen’s. As a means of connecting denominational higher education with non-sectarian higher education, the idea of University federation gained traction in the 1880s. The example of Canadian federation was no doubt influential. The Federation Act of 1887 allowed denominational schools to federate with the University of Toronto. The denominational schools would teach courses and organize community life; the “provincial University” would set examination standards and give degrees.

The idea worked. Wycliffe and Knox federated almost immediately; Victoria federated after a couple of years of sharp debate; Trinity entered in 1904, and St. Michael’s (1910) followed (it had to agree to admit female students). Wycliffe and Knox were already located a t the University campus; Victoria moved in from Cobourg, and Trinity moved up from Queen Street West in the 1920s.

t the University campus; Victoria moved in from Cobourg, and Trinity moved up from Queen Street West in the 1920s.

St Augustine’s Seminary (1913)

St. Augustine’s Seminary (pictured at left) was founded as the major seminary of the Roman Catholic archdiocese of Toronto. The building was funded by Eugene O’Keefe, the brewer and philanthropist, and was erected on a 62-acre site on the Scarborough bluffs.

Emmanuel College (1928)

In 1925, the United Church of Canada was created out of the Methodist Church, the Congregational Church, and most of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. Knox College remained Presbyterian, but all the board, all the faculty, and most of the students at Knox joined the United Church. They created a new theological school called Union College in 1926, which merged into the Faculty of Theology at Victoria University in 1928. The resulting theological school was called Emmanuel College.

Regis College (1930)

Regis was founded in 1930 as an undergraduate college. It was located at first on Wellington Street in Toronto. A theological program was added in 1943. It received the name Regis in 1954. In 1956 it received authorization to grant ecclesiastical degrees, and in 1957 St. Mary’s University in Halifax began granting degrees on its behalf. It moved to North York in 1961. In 1976 it moved downtown to St. Mary Street, near Yonge Street, and in 2008, in affirmation of its identity as the Jesuit college at the University of Toronto, it moved on campus to its present location in Queen's Park.

The Toronto Graduate School for Theological Studies (1944)

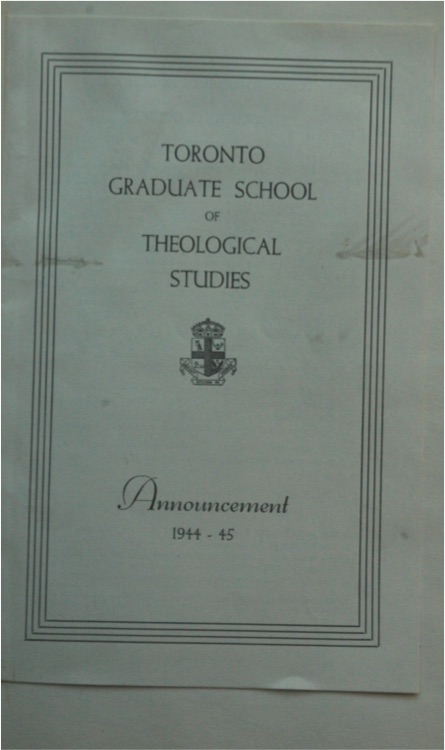

The Toronto Graduate School for Theological Studies (1944)

The TGSTS was created in 1944 as a federation of Emmanuel, Knox, Trinity, and Wycliffe Colleges to collaborate in offering programs leading to the Master of Theology (ThM) and Doctor of Theology (ThD). Ecumenical cooperation at this level was a remarkable breakthrough; Emmanuel and Knox represented the two sides in the bitter disputes around the founding of the United Church of Canada in 1925, while Trinity and Wycliffe represented opposing sides in the long-standing “churchmanship” controversies.

TGSTS was incorporated in 1964.

The origins of the TST

Vatican II and St. Michael's

Pope Paul VI issued the Council's decree on ecumenism in 1964. The decree was welcome at St. Michael's, which was already closely connected to the University of Toronto, and now had encouragement from the Vatican to bring its theological faculty into closer alignment with the other schools. Particularly influential in this process was Gregory Baum (1923– ), a professor who was also the founding editor of The Ecumenist, and who was indefatigable in supporting ecumenism not just on campus but across the country. Archbishop Philip Pocock, the chancellor of St. Michael's, and Fr. John Kelly, the president, were also strong supporters of ecumenism. St. Michael's joined the TGSTS in 1965.COCTET (1968–1969)

Vatican II, prominently among several factors, stimulated a considerable enthusiasm for further ecumenical rapprochement among the Toronto colleges. A study committee in 1967–1968 began to consider how to bring the colleges more closely together, and in May 1968 this group evolved into the more formal Committee on Cooperation in Theological Education in Toronto. Bill Fennell, the principal of Emmanuel (pictured at left), chaired. COCTET included the president of Regis College from the beginning, and later a representative from St. Augustine's. The Atkinson Foundation of the Toronto Star contributed $10,000 to the project. The dierctor of the American Association of Theological Schools, as it was then styled, offered counsel.

Committee on Cooperation in Theological Education in Toronto. Bill Fennell, the principal of Emmanuel (pictured at left), chaired. COCTET included the president of Regis College from the beginning, and later a representative from St. Augustine's. The Atkinson Foundation of the Toronto Star contributed $10,000 to the project. The dierctor of the American Association of Theological Schools, as it was then styled, offered counsel.

Members of the first meeting of COCTET were William Fennell (Emmanuel, Chair); J. Charles Hay (Knox, secretary); John C. Kelly and Elliot B. Allen (St. Michael's), Howard Buchner and John C. Hurd (Trinity), Leslie Hunt and Reginald Stackhouse (Wycliffe), A.B.B. More (Victoria), J. Stanley Glen (Knox), Frederick E. Crowe and E.F. Sheridan (Regis), and David Schuller (AATS).

Among the questions for COCTET to decide were:

- =Should the schools merge into a union college, or retain their identity as members of a consortium? (COCTET favoured a consortium.)

- -Should the TST grant degrees, or should the member colleges continue to grant degrees? (COCTET favoured leaving degree-granting to the colleges.)

- -Should the graduate teaching of theology be done under the auspices of conortium, or in the University of Toronto? (COCTET favoured the consortium.)

In May 1969 COCTET issued a press release, announcing that the Toronto School of Theology was being founded by the seven colleges, and that its operations would begin in September (1969). In addition to the Th.M. and Th.D. degrees already administered by the TGSTS, the schools would now also collaborate on basic degrees (the M.Div. and M.R.E.).

However, the M.A. and the Ph.D. at St. Michael's were not included in the arrangement. St. Michael's preferred to administer these on its own, through a new unit which it called the Institute of Christian Thought (ICT). This decision caused some bitterness at TST, which felt undermined. The reasoning at St. Michael's was that (1) TST would become so overwhelmingly interested in professional programs that it would give short shrift to graduate degrees; and (2) it would be preferable to connect the M.A. and Ph.D. with the University of Toronto, which was expected to create a graduate unit in religious studies. But ICT and TST created a Joint Committee on Admissions and Arrangements in 1972, and established an arrangement whereby students enrolled in other TST colleges could take the M.A. and Ph.D. programs, and graduate from St. Michael’s. For a host of reasons, however, the ICT failed to flourish; it was dismantled in 1979, and administration of the M.A. and Ph.D. programs at St. Michael's was transferred to TST, where it remains today.

TST Begins

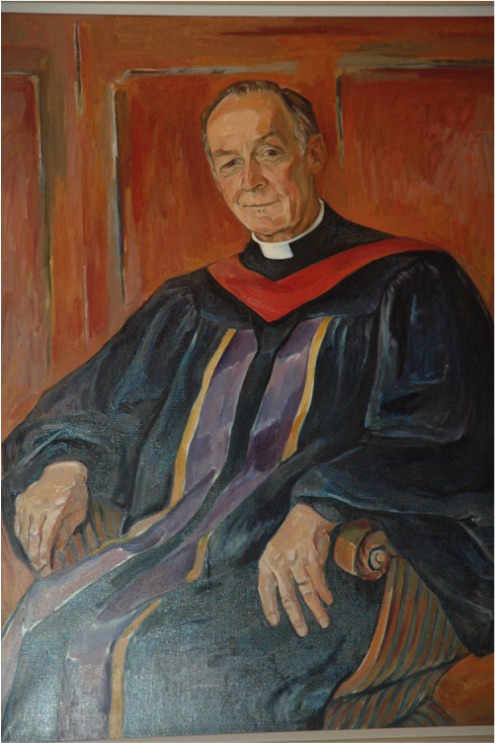

The first Director. C. Douglas Jay, pictured here, a professor of philosophy of religion and theological ethics at Emmanuel College, was appointed the first Director. He would serve from 1969 to 1980. It's generally acknowledged that his low-key manner, and his highly consultative and patient but persistent style of leadership, were  essential elements in the success of TST. His academic staff included Prof. John Hochban, S.J., registrar, and Prof. Charles Hay, director of advanced degree studies. Robert Blackburn and Grant Bracewell, librarians at Victoria and Emmanuel, coordinated library arrangements for the consortium. Assistant directors for field education and continuing education were also appointed. Campus space was found for the TST offices.

essential elements in the success of TST. His academic staff included Prof. John Hochban, S.J., registrar, and Prof. Charles Hay, director of advanced degree studies. Robert Blackburn and Grant Bracewell, librarians at Victoria and Emmanuel, coordinated library arrangements for the consortium. Assistant directors for field education and continuing education were also appointed. Campus space was found for the TST offices.

TST fires up. Six of the colleges began cooperating immediately (St. Augustine's required a year to prepare). Common approval of course offerings, according to a common standard and in a common timetable, was essential; this process was completed quickly, and a TST-wide course bulletin was published in time for the new academic year in September. Rooms were allocated. A few TST-wide courses were developed, including "Introduction to New Testament" and a survey course in Church history. A TST Board of Trustees was appointed. In 1970, TST was incorporated. (Formally, the letters patent for the incorporation of the TGSTS were amended with a new name and a revised statement of objectives.) TST is not chartered as an educational institution, but operates as a not-for-profit corporation under the laws of Ontario. TST applied for and received associate status with AATS, the accrediting agency.

Issues and successes. The success of TST depended in large measure on the cooperation, trust, and personal chemistry of the college heads. Stanley Glen of Knox and Leslie Hunt of Wycliffe were known to be cool to the project, although most of their faculty members were committed. At St. Augustine's some who thought that Vatican II had gone too far were also resistant. But TST's beginnings were promising. Ecumenical interest was strong, and in TST's first year, 96% of students took at least one course outside their home college.

Organizational structures. TST has a By-law providing for a Board with representation from the member colleges. An Academic Council sets academic policy. Its committees include a Basic Degree Council, a Graduate Studies Council, and a Curriculum Committee. The college heads meet at least once a month for consultation; the college registrars meet roughly once a month as well; the college librarians meet five or six times a year; and the finance directors and development directors meet at more irregular intervals. Graduate students across TST have an association called the TST Graduate Students Association (TGSA), and basic degree students across TST, as of 2016, have their organization called the TST Roundtable.

TST and the University of Toronto, to 1979

Church influence at U of T before 1969

The federated colleges and religious culture. Although the University of Toronto Act prohibited lectureships in divinity, the campus ethos was distinctly Christian through most of the 1960s. The Federation Act of 1887, section 81, authorized University College to make regulations for religious instruction and attendance at worship. Entering federation in 1904, Trinity College negotiated a concession that it could impose curriculum requirements in religious knowledge. Seeing that a precedent had been established, Victoria and St. Michael's followed suit. University College didn't require a course in religious knowledge, but it did allow a "religious knowledge option," often taught by theological faculty members at Knox or Wycliffe.

The University of Toronto relied on church resources in numerous ways. The church-supported federated schools employed some of the University's most distinguished faculty members, including Northrop Frye (an Emmanuel graduate and United Church minister) at Victoria, and Marshall McLuhan at St. Michael's. Two of the University's most influential presidents were clergy (Sir Robert Falconer, 1907–1932; Henry Cody, 1932–1945), pictured at right. One of U of T's first interdisciplinary  centres, the Centre for Medieval Studies, depended heavily on church-related medievalists from the federated colleges. The historian Catherine Gidney, in A Long Eclipse (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004), has identified a strong religious culture in English Canaidan universities into the early 1960s, as seen in official pronouncements, curriculum, student life, and institutionalized moral standards.

centres, the Centre for Medieval Studies, depended heavily on church-related medievalists from the federated colleges. The historian Catherine Gidney, in A Long Eclipse (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004), has identified a strong religious culture in English Canaidan universities into the early 1960s, as seen in official pronouncements, curriculum, student life, and institutionalized moral standards.

A new regime. In 1966 the federal government, which had financially supported post-secondary institutions directly, decided to give educational funding to the provinces for distribution. Canada had supported denominational schools, but Ontario didn't, except for half-funding for theological programs. The financial stress on the federated universities moved them to consider new, more subordinate relationships with U of T. In 1970 a wide-ranging set of changes in the curriculum in Arts and Science at U of T, called the Macpherson reforms, eliminated the undergraduate "core curriculum" in favour of a self-service curriculum allowing students to choose their courses. This change reduced college influence in the education of undergraduate students. As part of this change, the religious knowledge requirement at the federated universities, and the religious knowledge option at University College, were eliminated. In 1974, by a Memorandum of Agreement between U of T and the federated universities, faculty members at the federated universities became members of amalgamated U of T departments. U of T would improve funding to the "feds", but would need to approve all future funded faculty appointments at the colleges, and would control promotion and tenure. All these changes reduced the influence of the federated universities, and therefore reduced the historic Christian connections of U of T.

As a measure of the decline of Church influence among "the feds", ordained faculty members virtually disappeared from undergraduate education. The most notable change was at St. Michael's. In the early 1950s St. Michael's had only one lay faculty member; in 1969 lay faculty members were in the majority; and by the 1990s almost no clergy or religious taught undergraduate students.

Religious studies at U of T

Theological professors taught U of T undergraduates until 1970. Many of the professors who taught undergraduate courses in religious knowledge in the federated schools had their primary appointments in theology. In the 1960s these included David Demson and John Webster Grant from Emmanuel, Eugene Fairweather, Derwyn Owen, Cyril Powles, James Reed, and John Hurd from Trinity, and Herbert Richardson and Richard Schiefen from St. Michael’s. Also, some persons with U of T appointments taught in the theological schools, such as Joanne Dewart  (later Joanne McWilliam), pictured at left.

(later Joanne McWilliam), pictured at left.

'Religious studies' develops as a secular academic discipline. In the 1960s and early 1970s, an academic unit for the study of religion from a 'secular' point of view took shape at U of T. This development was part of a larger trend; departments of religious studies were on the rise in English and American unviersities in the 1960s. 'Religious studies' was often seen, in those pre-post-modern days, as more scientific and value-free than theological studies. Ninian Smart, a professor at the University of Lancaster, U.K., was a pioneer in religious studies as a secular discipline, and he promoted religion departments in the U.K. and the U.S.A.

In 1965 a University commission chaired by a law professor, Bora Laskin (later chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada), recommended master's and doctoral programs in religious studies. Against those who feared that the teaching of religion would be a mask for proselytism, Laskin replied that one might as well abolish departments of politics and economics on the grounds that students might get indoctrinated by Conservative or Liberal ideas.

A centre for the study of religion opens at U of T. By 1969 the religious knowledge teachers from the federated universities had organized themselves into what they called the “Combined Departments,” appointed one of their number as chair, agreed to open some of their courses to students from other colleges, drafted a prospectus for an interdisciplinary concentration in religion, and proposed a change in the name of their discipline to “religious studies”. They then formed a committee, with additional members from TST, other University departments, and the Institute for Christian Thought at St. Michael's, to develop a proposal for a Centre for Religious Studies. The proposal was approved in 1973 by the executive of the humanities division and the council of the School for Graduate Studies. The proposal went to a review by external assessors. These included Ninian Smart. They raised caveats. Faith-based disciplines like Christian theology should be excluded. (Islamic theology and Jewish theology weren't seen as problems.) The reviewers particularly warned against using too many faculty members from TST. That, they argued, would swing the hegemony of the program to Christianity. The graduate dean was incensed at Smart's implication that the University was incapable of managing its resources; others, suspicious that TST was trying to gain a foothold in the University, applauded Smart's strictures.

Supporters, including the graduate dean, fought hard in favour of the proposal, and the Centre for the Study of Religion was established in 1976, offering the MA and PhD in religion. The mandate of the Centre excluded theology.

Note: U of T now offers an undergraduate program in religion as well, and the Centre has become the Department for the Study of Religion.

Evaluation. The development of religious studies as an academic discipline may reflect, on the one hand, a decline in participation in church life, but, on the other hand, a continuing interest among students and resesarchers in the kinds of questions that religions raise. However, the institutional distinction between religious studies and theology wasn't a foregone conclusion. At many universities (e.g., Oxford, Cambridge, McGill, Yale, Chicago), theology and religion operate in the same departments. The differentiation at Toronto arose for historical reasons dating back to the first U of T Act in 1849, which prohibited lectureships of divinity, and was reinforced by the influence of Ninian Smart. The U of T culture has been scrupulous in differentiating religious studies from theological studies, and careful institutional and conceptual boundaries are maintained between the two. Some, with regret, have seen the situation as expressing and promoting academic territoriality, especially as academic departments are naturally competitive for prestige, funding, and students. In practice the boundaries have been porous, since a significant though not overwhelming number of TST professors have had status appointments in religion (today the number is about fifteen), and many areas of research are equally at home in theological studies and religious studies. Moreover, the University culture now promotes interdisciplinarity.

Intersetingly, in the 1980s Ninian Smart himself repudiated his earlier rigid distinction between religious studies and theological studies as excessively "purist".

The Memorandum of Agreement, 1979

TST envisions a closer relationship with U of T. As early as COCTET, TST wanted to preserve and develop the close relationships with U of T enjoyed by the three federated universities and the two federated theological colleges. In 1971 Director Jay launched a series of meetings on this theme. One idea was that U of T would grant TST's degrees in theology; John Evans, the president of U of T, indicated in 1973 that such an arrangement could be possible, if the U of T Act could be sutiably amended and if the academic quality of the theological programs could be verified. A working group of U of T's Academic Affairs Committee in 1975 affirmed the TST’s high academic standards and international reputation, and considered that closer relationships would be “mutually beneficial and should be encouraged.” It recommended some form of affiliation between TST and U of T.

It emerges that a closer relationship with U of T may have positive financial consequences. Ontario theological schools were still receiving half-funding (one-half a basic income unit or BIU per student), and from 1971 they jointly began advocating for an increase. In the middle of 1975 the Ministry announced a doubling of grants to one BIU per student, but only for theological schools whose degrees were conferred by an associated university. (Among other things, the government understood that the funding of professional education helped employment rates.) Some universities in Ontario would qualify for this largesse immediately ─ Queen’s, St. Paul’s, Western Ontario ─ but the TST schools would need to find a way to have their degrees conferred by the University of Toronto. The obvious catch was that the U of T Act explicitly prohibited it from conferring degrees in theology.

Concrete negotiations begin. In 1975 TST and U of T began what Director Jay would later call “intricate and extensive” negotiations, which would last three years. The most difficult issue was that the TST colleges generally wanted to maintain their autonomy, while the University needed to protect the academic standards of any programs that it was seen to sponsor. Moreover, the increase in government funding depended on U of T's granting theological degrees, but the theological colleges wanted to grant their own degrees. There are different stories as to who invented the finally successful formula, but on a blizzard-bound morning in January 1977 the negotiators agreed to the magic word “conjoint”: degrees in theology should be awarded by each of the TST member colleges conjointly with the University of Toronto.

Dissent emerges. Many at U of T doubted whether theological studies, as based conceptually in a faith commitment, could be a serious university discipline. However, the chair of the Centre for the Study of Religion, Willard Oxtoby, replied that “a modern university mu st reflect long and hard before it excludes from its purview, or declares itself uninterested in, so mighty a matter as theology in human life.” Oxtoby recognized that the objections, in part, arose from the fact that U of T was so recently emerging from the context of Christendom; many wanted the University to keep their experience of a repressive Christianity far away. It was specifically an issue with Christianity; Oxtoby noted that no one seemed to object to his own area of teaching, which was Islamic theology. Another objection was that U of T wouldn't be administering the programs for which it would be giving (conjoint) degrees. This was the objection of the dean of the School of Graduate Studies, John Leyerle. He was overruled by the president of the University, James Hsm, who said that as TST was an external body, the matter came under his own authority, not the School of Graduate Studies.

st reflect long and hard before it excludes from its purview, or declares itself uninterested in, so mighty a matter as theology in human life.” Oxtoby recognized that the objections, in part, arose from the fact that U of T was so recently emerging from the context of Christendom; many wanted the University to keep their experience of a repressive Christianity far away. It was specifically an issue with Christianity; Oxtoby noted that no one seemed to object to his own area of teaching, which was Islamic theology. Another objection was that U of T wouldn't be administering the programs for which it would be giving (conjoint) degrees. This was the objection of the dean of the School of Graduate Studies, John Leyerle. He was overruled by the president of the University, James Hsm, who said that as TST was an external body, the matter came under his own authority, not the School of Graduate Studies.

U of T reviews TST and approves a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA). The University naturally required verification of the academic quality of TST’s programs. TST produced a substantial self-study, and U of T commissioned three external appraisers (R.B.Y. Scott of Princeton, Claude Welch of the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley; and Wilfred Cantwell Smith of Harvard). They reported favourably. The Ontario Councl of Graduate Studies ruled that the programs didn’t need its approval since they wouldn’t be attracting full formula funding from Ontario, but only 1 BIU per student; thus in the provincial funding system these were on a par with undergraduate degrees, not graduate degrees. U of T's Academic Affairs Committee debated the matter vigorously, and finally recommended the drafting of an MOA. This was done, and approved with revisions by U of T, the TST, and the TST member colleges; the government of Ontario indicated that the MOA would qualify the TST colleges for increased funding. The MOA depended on a legislative amendment to the University of Toronto Act, allowing conjoint degrees in theology; this was secured.

Two programs are excluded. It was only at this point, in May 1978, that the TST discovered that the M.A. and Ph.D. degrees would not be included as conjoint degrees. The outside appraisers had included these programs in their reports. But U of T declared that they were not TST degrees but St. Michael's degrees, and that anyway (in Douglas Jay’s summary of President Ham’s words) the M.A. and Ph.D. presented “a particular difficulty to the Graduate School since they duplicate existing nomenclature.” A sentence was added to the MOA committing all parties to continue discussing the place of the M.A. and Ph.D. degrees. But from that point on, these were "non-conjoint" degrees.

The MOA is signed. The parties to the agreement assembled for a formal signing in February 1979 (pictured above). President Ham wrote in a report to U of T, “In the staff and the libraries of the member institutions of the Toronto School of Theology there resides a wealth of scholarly resources which, when effectively combined with the University’s strength in the languages, history and culture of the heartlands of the great religions of the world, will make Toronto a centre of really extraordinary strength in religious studies.”

The MOA has been renegotiated and revised several times. New agreements were reached in 1983, 1989, 1994, 2004, and 2014. Typically there have been themes of interest in each negotiation, such as academic freedom in 1989 and quality assurance in 2014.

Administrative consequences. As U of T required common TST-wide standards for ithe conjoint degree programs, the member colleges began a busy process of negotiating agreement on a variety of matters. For example, the member colleges varied in the number of courses required for an M.Div.; this matter had to be settled. Most colleges had non-credit degree requirements, such as field placements; these had to be transparent, and preferably eliminated. A Basic Degree Handbook covering all TST colleges was hashed out. College registration systems were integrated into U of T's system. Acocrdingly, U of T's systems in such areas as course coding and the reporting of marks were accepted.

A function of the conjoint degree system has been that whenever new policies needed to be developed, as in matters of academic discipline, non-academic discipline, professional behaviour in field placements, and the like, the default has been for the TST colleges to work together to adapt U of T policies. This has spared TST from considering each issue 'from scratch'.

Evaluation. The first MOA identified its purpose as qualifying the theological colleges for increased government funding. This was really too narrow a statement, since much more was envisioned, and much more has resulted. The 2014 MOA acknowledges the original importance of an increase in funding, but states more fully,

Among the several benefits of this arrangement between TST Member Institutions and the U of T are enhanced resources and quality assurance. Accordingly, the parties to this Memorandum and their respective governing bodies have entered into this agreement for the express purposes of:

• Promoting the academic quality of theological studies;

• Strengthening opportunities for students to engage in theological studies; and

• Facilitating research and inquiry in this area by students and faculty.

TST has indeed benefited from the rich academic and other resources of its U of T environment, and from U of T's persistent attention to educational quality. Also, U of T exercised a kind of gravitational pull that encouraged the TST colleges to accept University policies and procedures, which spared them many internal debates and possible divisions. In addition, as U of T is regularly ranked among the top research universities in the world (see cha rt at left), its endorsement of TST's theological degrees has increased their value for graduates.

rt at left), its endorsement of TST's theological degrees has increased their value for graduates.

Tensions are bound to arise, however, between the University's mission and the mission of the member colleges. While the member colleges accept the mission statement of the University, they are also commited, perhaps primarily, to service to the Church. In a world of limited resources of time and money, it's necessary to establish priorities, and theological schools are sometimes stressed by the need to attend to their obligations to the Church and the gospel while also serving other good purposes.

Programs

TST had four degree programs when it began. Before 1970 graduates of theological programs earned simply a college diploma, or a bachelor's degree (Bachelor of Divinity; Bachelor of Sacred Theology), or a Licentiate, depending on the school and the patterns of the denomination. From 1970 North American theological education began to agree on the nomenclature Master of Divinity for graduation from a three-year post-baccaluareate program. In the United States the M.Div. was generally seen as a professional graduate degree, since it operated on a post=baccalaureate level; in Canada it was generally seen as a second-entry undergraduate degree, since it was the first program in a new discipline.

At first TST had four programs:

- The Master of Divinity (basic degree, professional);

- The Master of Religious Education (basic degree, professional);

- The Master of Theology (advanced degree, academic);which built on the M.Div.; and

- The Doctor of Theology (advanced degree, academic), wh ich built on the Th.M.

Lay theological education, originally ignored, came to be supported. The assumption in 1969 was obviously that all basic degree students had professional goals, and that all advanced degree students had begun as students with professional goals. But some students simply wanted to study theology for its own sake. Around 1973 Wycliffe introduced the Master of Religion program, which required three years of study but had no required professional component. Students could also register for the M.A. at St. Michael's. In the 1990s demand for lay theological education seems to have blossomed, and around 1998 TST colleges began introducing the Master of Theological Studies degree, a two-year academic program. (The Wycliffe M.Rel. was eventually closed.)

The D.Min. was introduced in 1978. At first TST had no professional advanced degree in theological studies. In 1972 the Association of Theological Schools, the accrediting agency in theological education, approved a professional doctorate called the Doctor of Ministry. TST opened its D.Min. program in 1978. Requirements for the D.Min. vary dramatically among the 170 or so North American theological schools that offer it. TST's version is among the most demanding, which has probably limited its competitive appeal.

A pastoral program for lay leaders was introduced. In the United States the program that has shown the greatest growth in the past twenty years or so is the "M.A. in ..," as a niche professional degree. Theological schools fill in the blank with areas of pastoral interest, such as "MA in Youth Ministry," "M.A. in Leadership," "M.A. in Counselling," and the like. Ontario doesn't allow the M.A. nomenclature for professional degrees, and the TST nomenclature is "Master of Pastoral Studies." This was begun at Emmanuel in 1998, and is now offered at Knox College as well.

Two colleges have unique programs reflecting some niche strengths. Regis College has a Master of Arts in Ministry and Spirituality, or M.A.M.S. (to avoid the implication that it's an M.A. degree in a particular area). It's often used by students intending to be spiritual directors in the Ignatian tradition. Emmanuel College has a Master of Sacred Music degree for church musicians. It's administered in connection with the Faculty of Music at U of T.

A conjoint Ph.D. was introduced in 2014. As indicated above, the first MOA in 1979 promised a conversation between TST and U of T about the possibility of a conjoint Ph.D. program in theological studies. Conversations did indeed occasionally happen, but fruitlessly. That's a long story. But in 2012 U of T agreed that TST could apply to begin a conjoint Ph.D. program. Professor Terry Donaldson of Wycliffe College was appointed the principal advocate to develop the application. Many meetings were held on the matter among TST faculty members, heads of colleges, administrators, and interdisciplinary partners at U of T. It was decided that, unlike the Th.D., which encourages students to focus fairly exclusively in a sub-discipline of theological studies, the Ph.D. would be cohort-based. All Ph.D. students, whatever their main interest, would take two core courses together. The program would have more extensive supervisory mentoring. It would place a more intentional and consistent emphasis on interdisciplinarity and methodology. After administrative approvals at TST and U of T, and a review by external assessors, the program was approved by governance and by the Ontario government. The Th.D. program is no longer open to new admissions.

A conjoint M.A. will be introduced in 2017. After the approval of the conjoint Ph.D., TST applied for a conjoint M.A. in theological studies. After an external review, this was approved in 2016 by TST and U of T governance, and by the Ontario government.

Multi-faith education has begun. After Mark Toulouse became principal of Emmanuel in January 2009, opportunities arose for the college to expand its faculty, curriculum, and community relationships in ways that would enable it to serve Muslims in Toronto. Later similar opportunities developed with the Buddhist community. Emmanuel now has a Muslim studies stream and a Buddhist studies stream in its Master of Pastoral Studies programs. These are conceived not as 'religious studies' programs for non-adherents, but as programs to serve leaders and members of these communities. Most faculty members in these areas have sessional appointments or contractually limited term appointments (CLTA's), but in 2016 Dr. Nevin Reda (pictured right) was appointed to teach Muslim studies in the professorial stream.

Multi-faith education has begun. After Mark Toulouse became principal of Emmanuel in January 2009, opportunities arose for the college to expand its faculty, curriculum, and community relationships in ways that would enable it to serve Muslims in Toronto. Later similar opportunities developed with the Buddhist community. Emmanuel now has a Muslim studies stream and a Buddhist studies stream in its Master of Pastoral Studies programs. These are conceived not as 'religious studies' programs for non-adherents, but as programs to serve leaders and members of these communities. Most faculty members in these areas have sessional appointments or contractually limited term appointments (CLTA's), but in 2016 Dr. Nevin Reda (pictured right) was appointed to teach Muslim studies in the professorial stream.

This was not the first multifaith initiative at TST. TST sought to make a joint faculty appointment with Jewish Studies in 1982, which fell through for jurisdictional reasons. Conrad Black, a TST trustee, donated a handsome endowment, called the Kaplan Fund, to support teaching in Judaism at TST. In 1987 TST moved unsuccessfully towards appointing Willard Oxtoby in Islamic Studies in 1987. St. Michael's for several years offered a popular Jewish Studies stream as part of its M.A. In 2008 discussions began with a prospective rabbinical school, which hopefully would have affilated with TST, but the project wound down with the ill health of the rosh yeshiva.

Canada needs spiritual care workers. Canada has an increasingly multi-faith social context, and institutions such as hospitals, the military, family counselling services, and schools, which once might have looked for Christian chaplains, now look for spiritual care workers. Such workers may operate from a particular faith tradition, but in a multi-faith context. In 2015 the Ontario government proclamed an Act that creates a regulatory college to oversee such workers. In 2016 TST, with U of T, created a conjoint Certificate in Spiritual Care and Psychotherapy with the intention tohat it will help persons train for membership in the College of Registered Psychotherapists of Ontario.

The arts. A TST faculty group is currently in discussion about developing a curricular stream in arts and theology. This has partly been stimluated by the "Mystical Landscapes" exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario, running from October 2016 to February 2017, which several faculty members and students at TST helped to conceive.

Indigenous studies. TST has enthusiastically taken up the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Several dozen courses currently address, in whole or in part, issues of Indigenous religion and social justice. TST recognizes that it needs to involve Indigenous Christians and other elders, and listen to them carefully, as it proceeds.

Evaluation. Although there's statistical reason to believe that church participation is declining, interest in theological education has diversified. In 1969 it could be assumed that only clergy and members of religious orders would seek theological education. (I can attest that when I began seeking out a theological school in 1968 that didn't expect me to be training for ministry, I found only one in North America — McGill — which is where I went.) But lay theological education, both for academic purposes and for purposes of lay leadership, has burgeoned.

A study could also be done of patterns in curricular developments over the decades, which would probably show how changes in the perceived needs of the Church, and changes in educational philosophies, research methods, and areas of interest, have influenced theological education significantly. One example given above is TST's re-thinking of the academic doctorate as it moved from a Th.D. to a Ph.D.

TST's building

For many years TST's office space was at the edge of the Victoria campus. Administrative offices for TST were housed for many years on an upper floor of 4 St. Thomas Street, in a building owned by Victoria University (the building no longer exists). Space was limited there; in particular, there was no room for meetings. It was also well removed from the centre of campus life, and had a very low physical profile. TST's leaders sought a solution that would give them a more conspicuous presence on the U of T campus, more space for administration, meeting rooms, and control over its facilities, preferably at a reasonable expense.

In the early 1980s a building on Queen's Park became available. At 47 Queen's Park Crescent East there was a handsome old  Victorian building, in some disrepair, which had originally been designed by David Dick (the architect for the Wycliffe College building) for Reuben Millichamp, a successful partner in a dry goods firm. It had been acquired by the Ontario government in 1921, and transferred to U of T in 1981. The latter used it to house the department of linguistics. St. Michael's had been eyeing it for many years, since it was adjacent to its campus. Leaders from U of T, TST, and St. Michael's worked out an agreement whereby U of T would lease the building to St. Michael's for $1 a year, with the understanding that St. Michael's would license its use to TST for $1 a year. TST would renovate and maintain the building.

Victorian building, in some disrepair, which had originally been designed by David Dick (the architect for the Wycliffe College building) for Reuben Millichamp, a successful partner in a dry goods firm. It had been acquired by the Ontario government in 1921, and transferred to U of T in 1981. The latter used it to house the department of linguistics. St. Michael's had been eyeing it for many years, since it was adjacent to its campus. Leaders from U of T, TST, and St. Michael's worked out an agreement whereby U of T would lease the building to St. Michael's for $1 a year, with the understanding that St. Michael's would license its use to TST for $1 a year. TST would renovate and maintain the building.

The necessary renovations were extensive, and cost TST over $895,000 (in 1981 dollars!). U of T's lease to St. Michael's, and St. Michael's licence to TST, were both executed on June 30, 1984.

Further renovations were undertaken. In 2004 improvements were required to improve the use of space, and to meet requirements of the Fire Code and the Building Code. It was decided to create offices for rental at below-market rates to faith-based organizations. In this way TST would be serving the Church, providing an ecumenical environment for small Christian organizations that might otherwise feel isolated from one another, and receiving revenue to cover maintenance costs. The renovations cost $450,000.

In 2016, the slate roof was replaced. It has a life expectancy of about a century.

St. Michael's licence to TST expires in 2026.

Academic freedom

In 1989 TST's negotiations for a new MOA with U of T were influenced by an issue of academic freedom that had arisen during the term of the previous MOA. Between June and September 1984 Emmett Cardinal Carter, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Toronto, removed or required the resignation of three faculty members of progressive theological outlook at St. Augustine's Seminary, one of them a tenured professor. This followed an investigation of the seminary by Marcel Gervais, the auxiliary bishop of London, which was commissioned because of concerns about doctrinal orthodoxy, formation for the priesthood, alleged homosexuality, and a party in January 1984 in a professor's apartment involving alcohol and woman students from Trinity College. The story made front-page news in the Globe and Mail over a period of weeks, in stories reported by Peter Moon and Stanley Oziewich, and also in The Varsity, the U of T student paper. Discussions followed among TST, St. Augustine's, U of T, and the archdiocese. The Association of Theological Schools dispatched a consulting team. The faculty members were not treated without compassion: the tenured professor received good references and was quickly appointed to an American university; a second faculty member was given full funding for a doctoral program; a third faculty member was given a position in a parish. But from the University's point of view, terminating faculty members for progressive views or for writing imprudent documents was a violation of generally accepted standards of academic freedom. The issue remained unresolved for a period of time, until in 1988 U of T demanded that Cardinal Carter accept its policy on academic freedom and related personnel policies. The Cardinal refused, and St. Augustine's was suspended from the MOA. The seminary thus lost government funding for its programs, and its students were removed from conjoint degree program registration, student services, and library privileges. In the following year, however, accommodation was reached on all sides, and St. Augustine's was restored to the MOA. In the years following U of T remained sensitive to issues of academic freedom at TST.

Ecumenism

Most though not all TST colleges have highly ecumenical student bodies. At several colleges, the student body represents literally dozens of Chrisitan and other denominations, including some of no stated affiliation. Ecumenical interchange is thus built into the classrooms and social settings of most colleges.

At the graduate level, ecumenical education across collage boundaries is a well established reality. Students registered in one college can freely take courses at other colleges. For the Ph.D. program, two of the eight required courses are TST-wide cohort courses. There's a tendency, indeed, for doctoral students to register in the college where their supervisor teaches, and that means that they will usually take courses from their supervisor; but, otherwise, there's no statistical tendency for students to choose courses offered by their home college.

At the basic degree level, however, most students now take courses at their home college. This is a dramatic (and disappointing) change from TST's early years. Some statistics will illustrate. The following chart compares sample semesters in 1977 and 2015 to show the percentage of student course registrations where the student took a course within his or her home college; this is for all basic degree students (MDiv, MRE, MTS, MPS, MSMus, MAMS). It indicates that students today are much less likely to cross college boundaries than their predecessors were in the heady early days of TST.

TST Basic Degree Students: Course Cross-Registrations: Percentage staying in home college

| College | % course registrations in student's own college, winter 1977–78 |

% course registrations in student's own college, fall 2015–16 |

| Emmanuel | 57 | 96 |

| Knox | 55 | 86 |

| Regis | 53 | 65 |

| St Augustine's | 29 | 97 |

| St Michael's | 43 | 76 |

| Trinity | 43 | 81 |

| Wycliffe | 45 | 90 |

In the early years of TST, John Hochban, S.J., the TST registrar, was particularly concerned to encourage Roman Catholic students to take courses from non-RC colleges, and vice versa. (Fr. Hochban's own home college of Regis has always done well in this respect.) He therefore published statistics of RC/non-RC course registrations every semester. On this basis, the contrast is even more dramatic;

TST Basic Degree Students: Course Cross-Registrations: Percentage crossing the RC/non-RC barrier

| College | Proportion of course registrations RC->non-RC or non-RC->RC, winter 1977–1978 | Proportion of course registrations RC->non-RC or non-RC-:>RC, fall 2015–2016 |

| Emmanuel (non-RC) | (to RC) 31% | 2% |

| Knox (non-RC) | (to RC) 27% | 5% |

| Regis (RC) | (to non-RC) 11% | 8% |

| St. Augustine's (RC) | (to non-RC) 15% | 1% |

| St. Michael's (RC) | (to non-RC) 17% | 7% |

| Trinity (non-RC) | (to RC) 33% | 10% |

| Wydliffe (non-RC) | (to RC) 22% | 3% |

From this point of view, TST has fallen far short of its ecumenical potential; it appears that the exposure of students to points of view outside the tradition of their college registration has declined significantly. To what extent this situation is the result of student choice, and to what extent the result of college direction, isn't known.

Possible explanations for the decline in course cross-registrations include the following:

- Ecumenical zeal in general has waned since the years immediately after Vatican II.

- There are broader cultural signs — for instance, in the political realm —that people prefer to listen to points of view they agree with, and avoid the others.

- Declining church memberships may have inclined denominational mentalities to turn inward.

- After the first generation of TST college leaders, who pioneered TST together and built up a warm personal chemistry, the second generation began to return to a "business-as-usual," self-protective attitude.

- For various reasons, degree requirements increased, and many could only be met by courses offered in the student's home college.

- The number of part-time commuting students increased, putting scheduling pressure on a few premium time slots from Tuesday to Thursday, which colleges filled with required courses. Students therefore had less opportunity to choose electives outside their college.

- Since TST has a system for transferring some funding to colleges in proportion to the number of students they teach, college leaders have a financial incentive to keep their students in their own college.

Quality assurance

TST's relation to U of T changed dramatically after it came under a new University-wide quality assurance program in 2011.

Before 2011. Formerly U of T had relied for this purpose primarily on the accrediting reviews of TST and its member colleges as conducted under the auspices of the Association of Theological Schools. The succession of MOA's laid down general academic standards for TST and its colleges, but before 2011 U of T had no systematic, consistent handle on TST's programs. From 1996 to 2010 U of T had an "Undergraduate Program Review  Audit Committee" (UPRAC) which probably should have covered TST's basic degree programs, but these were overlooked. In 2001 the Ontario Council of Graduate Studies (OCGS) conducted its first review of TST's Th.M. and Th.D. programs, and it reported favourably, but OCGS was independent of U of T.

Audit Committee" (UPRAC) which probably should have covered TST's basic degree programs, but these were overlooked. In 2001 the Ontario Council of Graduate Studies (OCGS) conducted its first review of TST's Th.M. and Th.D. programs, and it reported favourably, but OCGS was independent of U of T.

"UTQAP" begins. In 2010 a group commissioned by the Council of Ontario Academic Vice-Presidents developed a plan for a province-wide quality assurance process that would combine the quality assurance functions of OCGS and UPRAC in a different kind of way. It would be a little more decentralized, allowing each university to make assessment decisions in the context of its own particular mission. It would also be more formative, that is, aimed towards improvement, whereas OCGS reviews were concerned that programs reached a satisfactory threshold of quality. Province-wide standards were approved, and each Ontario university was asked to develop a quality assurance process consistent with the province-wide template. The University of Toronto created its U of T Quality Assurance Process (UTQAP) in 2011. This system included a process for the cyclical review of every academic unit; the review involves a self-study and a visit by a team of external assessors. TST was one of the first academic units, perhaps the first, that was required to undertake a cyclical review under UTQAP. TST submitted its self-study in December 2011, received an external reviewing team in January2012, and received a report back in April 2012.

Some program changes were required. The reviewing team found TST's M.Div. program strong and its other basic degree programs very satisfactory, but it had concerns with the Th.D. program. It identified no problems with the sheer academic quality of TST's graduate faculty, students, courses, or theses. But the team felt that TST hadn't realized its full potential. It suggested that TST needed to work more closely with U of T, to develop stronger interdisciplinary connections. It found that doctoral students were too much 'on their own' in a program which even at the best of times can be a little lonely; it suggested a more systematic emphasis on the faculty mentoring of doctoral students, and a cohort-based approach that would help doctoral students work more collaboratively. It recommended the development of a more coherent TST-wide faculty research culture as opposed to a college-by-college research culture. It suggested careful faculty complement planning. It recommended greater administrative efficiencies to help get doctoral students more quickly through their program. These suggestions fed into the development of the new conjoint Ph.D. program and onto the agendas of the heads of colleges and graduate faculty.

The new UTQAP regime shaped the discussions for the MOA of 2014. Since the early 2000s U of T's general academic ethos had been what Vatican II would have called 'subsidiarity,' favouring decentralization, with decision-making delegated to the lowest appropriae level. As a result, not just TST but departments across the U of T had made decisions on their own with what looked, in retrospect, like insufficient consultation and communication. UTQAP was developed to ensure a more consistent observance of quality standards across U of T, while still allowing for local initiative and latitude. The work of the office of the Vice-Provost Academic at U of T was revved up accordingly. The 2014 MOA was conceived as applying these principles to TST. U of T has no direction to give to TST colleges or faculty members as to the substance of what they teach, and it allows each academic unit some liberty to interpret regulations in the way that best fits their local context, but the formalities of teaching appointments, accountability structures, admissions, program requirements, curriculum review, academic discipline, and the like need to be carefully observed.

There were some other consequences. TST was for the first time required to reimburse U of T for the cost of numerous services that it had formerly received for free, such as Internet connectivity, email, and learning technology platforms. TST leaders thought that this was fair, although, naturally, a little financially painful. TST accepted U of T's policy on 'teaching stream' faculty members, which allows some TST professors to concentrate on teaching without being required to produce original research. U of T wanted all TST's non-conjoint programs to be clearly distinguished from conjoint programs; non-conjoint students would be removed from U of T's registration system, and wouldn't have U of T student identification cards ("T-cards"). They wouldn't have access to student services and wouldn't have library privileges (unless they purchased them).

Evaluation. Bringing TST under UTQAP, and the provisions of the new MOA, have been double-edged for TST. The culture of compliance has increased TST's administrative workload considerably, especially given that TST for many years largely flew under U of T's radar. But the burdens of a compliance culture are a common pattern in recent North American higher education. Another worry is that, while the current U of T administration is highly supportive of theological education, the new UTQAP regime might allow a less friendly U of T administration in the future to create obstacles to progress. There's probably no question that TST thinks much more consistently now about quality assurance issues than it did before UTQAP, and this kind of attention likely had paid dividends for academic excellence, operational consistency, concern for studetns, and reputation. And there are readier opportunities than before for fruitful interchange with other academic units at U of T, which enriches research and teaching.