Yahweh Faithful and Free

Ezekiel's Response to Exile (From Israel in Exile)

Ralph W. Klein

Among those deported from Jerusalem to Babylon in 597 were King Jehoiachin and Ezekiel the priest, the son of Buzi (1:3).Although Jehoiachin had ruled for only three months, his importance and power continued well into the Exile. Archaeologists have discovered seal impressions in Palestine inscribed with the words "Belonging to Eliakim, the steward of Yaukin," perhaps implying that Jehoiachin was recognized at least by some people as the legal king of Judah until the final destruction of587 .2 In Babylonian documents Jehoiachin is mentioned as "the king of Judah," and it is reported that his five sons were given food from the royal storehouse. Thus, Jehoiachin retained hisstatus as king even in exile. With the accession of Amel-Mardukto the Babylonian throne in 561, Jehoiachin was released from

1.See Walther Zimmerli, Ezechiel, BKAT 13 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1955-69), and idem, the essays reprinted in Gottes Offenbarung, TBü 19 (München: Christian Kaiser, 1963), and Studien zur alttestamentlichen Theologie und Prophetie, TBü 51 (München: Christian Kaiser, 1974). Also useful are the commentaries of Walther Eichrodt, Ezekiel, OTL (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1970), and John W. Wevers, Ezekiel, NCB (Greenwood, S.C.: Attic Press, 1969). Among comparative studies we refer to Dieter Baltzer, Ezechiel und Deuterojesaia, BZAW 121 (Berlin and New York:Walter de Gruyter, 1971), and Thomas M. Raitt, A Theology of Exile:Judgment/Deliverance in Jeremiah and Ezekiel (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1977).

2.See the discussion by Bustenay Oded, Israelite and Judaean History, ed.J. H. Hayes and J. M. Miller, OTL (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1977), pp. 481-82. According to this theory, Eliakim administered the crown property of Jehoiachin.

prison and given special honors (2 Kings 25:27-30). If Jehoiachin was considered the legitimate king even after his deportation, it follows that Jehoiachinís uncle Zedekiah had no legitimate claims to the throne he occupied from 597 to 587, or that, at the least, no hopes of deliverance from Babylon were to be placed in him.

Ezekiel himself seems to have been of this opinion. Not only do we find sharp words of criticism against Zedekiah and his policies (17:5-6, 11-21; 21:25-26), but the dates scattered through-out the book reckon time from the exile of Jehoiachin (1:2; cf. 33:21; 40: 1) and thus implicitly offer a snub to Zedekiah.

One can learn a great deal about the significance of Ezekiel by studying the thirteen dates that are original in his book.3

- Ezekielís call occurred in 593. Although Zedekiah had loyally gone on a mission to Babylon in 594 (Jer 51:59), by mid-summer 593 he had convened a group of rebel states in Jerusalem (Jer. 27-28) whose optimistic hopes Jeremiah forcefully denounced. If we can judge by the uncompromising announcement of judgment against Judah and Jerusalem in chapters 1-24, Ezekiel opposed this revolt with equal vigor. These two prophets saw the historical inevitability of Nebuchadnezzarís victory and theologically affirmed it.

- The final date given in Ezekiel is 571 (29:17). While some materials in the present book come from a later time, the proph-etís ministry itself can be assigned roughly to 593-571. Ezekiel, therefore, prophesied both before and after the final destruction of Jerusalem in 587. He was a later contemporary of his Pales-tinian colleague Jeremiah (626-580s) and preceded Second Isaiah (550-540) by nearly a generation. The latter fact accounts in part for the far different emphasis and tone in the two prophets who worked in the Babylonian Exile.

The oracle dated to 571 also helps us to see that Ezekiel wasable to change or modify an earlier word of God so that it would

- See K. S. Freedy and D. B. Redford, "The Dates in Ezekiel in Relationship to Biblical, Babylonian and Egyptian Sources," JA OS 90 (1970) : 462-85. The date in 24:1 MT is not original but was added from 2 Kings 25:1.

correspond to the actualities of history. According to 26:7ff., Tyre was to fall into the hands of Nebuchadnezzar and be totally destroyed. Despite a thirteen-year siege, however, the Babylonian king came up shorthanded: Tyre was not destroyed and plun-dered. To compensate Nebuchadnezzar for his trouble, Yahweh promised him the land of Egypt as his recompense (29:19-20). Thus Yahweh, according to Ezekielís interpretation, remained faithful to his original promise, though he was free to adjust his word to fit the contingencies of history.

c. Three of the four visions in Ezekiel are given special emphasis by being supplied with dates (1:2; 8: I; 40: 1).4 Zimmerli sees symbolic significance in the year number (twenty-five) of the final vision (see below, n. 25).

d. Seven of the dates fall in the hectic tenth-twelfth years, that is, during the final siege of Jerusalem. Not incidentally, five of these are linked to oracles against Egypt. Egyptís meddling in Palestinian affairs was-as usual for those times-militarily fruit-less and spiritually a disaster.

e. The oracle reporting the fall of Jerusalem is emphasized by providing it with a special date (33:21). This event marked a transition in Ezekielís ministry from words of judgment against Judah and Jerusalem (chaps. 1-24) and against the nations (chaps. 25-32) to words of hope (chaps. 33-48). Editors seem to have underscored this transition by the motif of Ezekielís dumb-ness. Seven days after the call of the prophet, Yahweh announced to him that he would be dumb and unable to reprove rebellious Israel (3:22-27). Later, God predicted that Ezekielís mouth would be opened on the day a fugitive would bring him word of Jerusalemís fall (24:26-27). That promise came true in 33:22: "He had opened my mouth by the time the man came to me in the morning; so my mouth was opened, and I was no longer dumb." Clearly this does not mean that Ezekiel was silent during the first seven years of his ministry-chaps. 1-32 are full of his words.

- Has the original date for the fourth vision (37:1-14) been lost? See Zimmerli, Ezechiel, p. 891. He suggests a date between 586/585 (33:21) and 571 (40: 1) for the vision of the dry bones.

Rather, it is an editorís way of showing how after the fall of Jerusalem Ezekielís mouth was opened to speak with boldness agreat new word, a word of hope.5

GODíS REAL PRESENCE IN BABYLON,HIS MOBILITY

The book begins with an account of the dazzling appearance of the likeness of the glory of Yahweh that knocked the prophet off his feet (chap. 1). Following this appearance Yahweh ad-dressed Ezekiel and outlined to him his commission and the cir-cumstances under which he would serve (2:1-3:15). Prototypes for such a call can be found in the calls of Micaiah ben Imlah (I Kings 22:19-23) and Isaiah of Jerusalem (Isa. 6), but differences from these earlier accounts also abound. Tradition and innovation go hand in hand.

To some people today chap. I seems to be esoteric nonsense; to others it represents the account of a visit from outer space. The truth lies in another place. Almost all the details of this vision can be traced to ancient Near Eastern religiotheological culture,6 or the idiom of theophanic descriptions in Israel. The intended effect of all the imagery: what Ezekiel saw there in Babylon was nothing else than Yahwehís own glory. That some details (e.g. the hands under the wings in v. 8) are not fully understandable and that the original picture of this chapter may have been supplemented by followers of Ezekiel are not to be denied.

The closer the text comes to describing the center of the theophany, the more words like appearance or likeness crop up(1:26-28). We would take this to be priestly reserve, a hesitancy to say that Ezekiel really saw God. In any case, the "man" he saw

- Robert R. Wilson, "An Interpretation of Ezekielís Dumbness," VT 22 (1972): 91-104, thinks the passages on Ezekielís dumbness," are attempts to defend him against the charge of failing to be a mediator for the people.

- See the recent monograph by Othmar Keel, Jahwe Visionen und Siegelkunst, Stuttgarter Bibel Studien 84/85 (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1977). pp. 125-273. Especially convincing is his interpretation of the four living creatures, w. 5-6. as "heaven bearers." See pp. 207-16 and illustrations 156c-66, 180, and 182.

on the throne had an upper body that gleamed like bronze, a lower body that appeared to be made of fire. The lapis lazuli throne was set on a "firmament" (cL Exod. 24: 1 0), and below it were four animals, each having four heads and four wings and beside which there were wheels within wheels.7 The whole conveyance could move easily in any direction and it was accompanied by a stormy wind, by the noise of an earthquake, Shad-dai, "many waters," and by brightness of various sorts-images that are the common coin of theophanic descriptions in the Old Testament.

It was nothing short of the authentic glory of Yahweh that appeared to the prophet. We read, for example, of the heavens being opened and of Ezekiel seeing visions of God (v. I). The animals who supported the throne had four wings and human features, not unlike the two-winged sphinxes that formed Yahwehís throne in the Solomonic temple. Their four heads represented the best of four categories of creatures: man, lion (king of the wild animals), the ox (supreme among domestic animals), and the eagle (the best of the birds)-only the finest could serve as this Godís thronebearers.8 The stormy wind that brought Godís chariot throne came from the north, Godís homeland in Israelite lore (Isa. 14:12; Ps. 48:2; Ezek. 38:6, 15; 39:2). The wheels were covered with eyes (v. 18), perhaps representing the all-seeingness or omnipresence of God.,í

This glory appeared to the prophet, not in Godís heavenly court (I Kings 22), or even in Yahwehís heavenly/earthly temple(Isa. 6), but "among the exiles by the river Chebar" (1:1, 3). The throne appropriately was quite mobile: the animals that bore it had wings, legs, and even wheels! The spirit was its driving force

- The wheels within wheels may come from a misunderstanding of thick, layered rims on certain depictions of wheels. See Keel, Jahwe-Visionen, pp. 263-67 and figs. 191-92.

- Keel, Jahwe-Visionen, pp. 235-43 and 271, makes a convincing case for an alternate interpretation of the wings and faces. The four wings show that the beings incorporate four cosmic winds while the heads, based on Egyptian art, stand for the four compass points: lion (south) , ox (north) , eagle (cast) , and man (west).

- Keel, Jahwe-Visionen, pp. 267-69, understands them as theological interpretations of nails driven into the rims of the wheels.

(v. 20). Because of the four animals, with their four heads and their wheels within wheels, the conveyance could take off in a new or different direction without turning (1:9, 12, 17). In short, a cascade of images declares Yahwehís mobility and his ability to be present in Babylon.

YAHWEHíS COMMISSIONING OF EZEKIEL

The commissioning speech which Ezekiel reports in chaps. 2-3 initiated a most difficult ministry. The prophet was addressed by Yahweh as son of man, a title used here and ninety-two other times in Ezekiel to indicate the prophetís servant character and the great condescension of God to speak with him at all. In this title and in the emphasis on Godís sending the prophet we find a testimony to Yahwehís sole responsibility for what happens to Israel, whether that be bad news or good.

Ezekielís commission, in any case, was to bring very bad news. His audience included all of Israel, both northern and southern kingdoms, presumably also all Israel which had existed from the Exodus to the Exile. They all, "they and their fathers" (v. 3), had rebelled against Yahweh; they all were nothing but a house of rebels. The prophet was to match their hardness: his forehead would be like adamant harder than flint. Success was not to be his standard. Rather, he was to speak the word of Yahweh 10 regardless of whether they listened or not (2:5, 7; 3:11, 27).

He was literally to incorporate and personify his message. At Yahwehís direction he swallowed a scroll filled-on both sides!-with nothing but lamentation, mourning, and woe (2:10). He would speak to them, "Thus says Yahweh" (2:4), knowing that their rejection of him was finally and simply a rejection of Yahweh himself (3:7). This bitter word tasted like honey to Ezekiel, not because he was masochistic (he was only one who had been sent) but because it was the word of Yahweh (cf. Jer 15:16). By definition Yahwehís words are a joy and a delight.

Godís actions, in judgment or grace, are never the final word in Ezekiel. Rather, Yahwehís actions are to enable Israel or the

- The expression "the word of Yahweh came to me/to Ezekiel" occurs more than forty times in the book.

nations to know and acknowledge the God who revealed himself in the simple self-proclamation, "I am Yahweh." Such "words of demonstration" occur nearly eighty times in Ezekiel." They come as the conclusion of words against the land of Israel (e.g. 7:2-4), at the end of oracles against foreign nations (e.g. 25:3-5), and at the end of words of salvation (e.g. 37:6, 13, 14). judging Israel and the nations or delivering Israel is only Godís penultimate goal. However hard Ezekielís message was from 593-587, it beat to the drums of Godís love. Ezekielís prophetic ministry was to help Israel recognize that Godís prophet had been among them (2:5; cf 33:33). To know this fact and to acknowledge the Lord who stands behind the prophet mean finally to confess the deeds of him who "says it all" in the words "I am Yahweh." Ezekielís no to Israel demonstrated Godís faithful-ness, but his hard no was also in the service of Godís ultimate yes. Godís fidelity allowed no ignoring of Israelís rebellion, but Ezekielís God was both faithful and free- he had wrath but he was not limited to it. In words from the Book of Ezekiel: "They [Israel] shall know that I am Yahweh their God because I sent them into exile among the nations, and then gathered them into their own land" (39:28; cf. 17:24).

LAMENTATION, MOURNING, AND WOE:GODíS NO TO ISRAEL

For the first six years of his exilic ministry Ezekiel had to announce a final no to Israelís history. That itself is an important voice from exile. False prophets might fail to step into the breach, or they might plaster over the troubles with cries of "Peace, peace," even when there was no peace (13:I-16), but Ezekiel, himself an exile, affirmed the finality and the correctness of Godís judgment. In his view there was no way around 587, either militarily or theologically.

- Walther Zimmerli has traced the history of this expression in earlier biblical literature and its function in the book of Ezekiel itself. See "Ich bin Jahwe," "Erkenntnis Gottes nach dem Buche Ezechiel," and "Das Wort des göttlichen Selbsterweises (Erweiswort), eine prophetische Gattung," Gottes Offenbarung, pp. 11-40, 41-119, 120-32. See nn. 5-9 on p. 43 for a list of the biblical passages involved.

"The end has come" is the way he put it in chap. 7. Aye, "the day of the wrath of Yahweh comes." The themes of Yahwehís day and of the end had been employed already by his predecessor Amos (5:18; 8:2) in the eighth century, but two factors made Ezekielís no to Israel especially difficult:

- A group existed in Jerusalem who thought the bottom had already been hit by the first deportation in 597. Having weathered that storm, they were ready to claim possession of the land, perhaps even to begin a rebuilding program (II: 3). They reacted to Godís judgment with opportunistic resignation: "Life has its ups and downs. The deportation of the ruling classes is our lucky break. Why, we already outnumber Abraham, that single man who nevertheless acquired land" (I 1: 15; 33:24).

- Secondly, Ezekielís no was spoken to Jerusalem, Godís chosen city. This prophet was after all a priest, and he pro-claimed his message among a people who sang, "If I forget you, 0 Jerusalem, let my right hand wither!" (Ps. 137:5). Yet his vision of the abominations in the temple (chap. 8) ended with an uncompromising, heartrending sight: six executioners were dispatched through the city to kill both old and young, not excluding women and children (9:6). Though some people were marked out for deliverance by a taw marked on their foreheads (9:4), the size of the destruction forced Ezekiel to cry out for a halt (9:8). Instead, the destruction moved from the people to the burning of the city and then to the departure of Yahwehís glory from the temple. On a vehicle not unlike the chariot throne of chap. 1, the glory moved to the threshold of the temple, then on to its east gate (IO: 19), and finally to the Mount of Olives (I 1: 23). One senses in this hesitant departure a grieving over the destruction it symbolized.

THE SIGN ACTIONS:ANTICIPATIONS OF JUDGMENT

Ezekielís well-known, often esoteric sign actions also proclaimed the fate of Jerusalem. What he experienced in them anticipated what Godís word was about to do against Jerusalem. The siege he acted out against a model of Jerusalem drawn on a brick was neither a war game nor a sign of the prophetís disturbed mental condition: it was a prediction of things to come (4:1-3). He also acted out a life under siege rations when he scraped together a few grains from the bottom of the barrel in order to stay alive (4:9, 10a), and he used his own hair to dramatize how Jerusalemís inhabitants would be burned in the city, killed in flight, or driven into exile (5:1-2). His orders were to march into exile with a pack on his back (12:1-16), eat his bread with quaking and dismay over the coming stripping of Jerusalem (12:17-20), or sigh with broken heart over the latest news from the homeland (21:6-7). He was ordered to set up a signpost pointing to Rabbah of the Ammonites and Judah-Jerusalem, two alternate routes of attack for the sword of Nebuchadnezzar. When the kingís divination procedures would lead him to attack Jerusalem first (21:18-23), he would hurry to carry out the divine sentence on a city legally convicted of sin. Even the death of Ezekielís wife was an occasion for proclamation: the prophet was forbidden to mourn for her. When asked the reason for his tear-less reaction to the loss of his eyeís delight, he pointed once more to the imminent destruction of the temple. The people would not mourn or weep for that either, he observed, but they would pine away in their iniquities (24:23).

WHY MUST THE END COME?

The offenses of Israel were omnipresent and wide-ranging in Ezekielís telling. The reader grows weary of the endless recounting of words like abominations, detestable things, idols and harlotries. Nevertheless, we need to survey some of the key indictments Ezekiel leveled against his contemporaries in order to understand the seriousness of the Exile in the prophetís eyes.

- Ezekiel 6. The mountains of Israel are here castigated for their high places, regular altars, incense altars, idols, and their sanctuaries on every high hill and under every green tree and leafy oak. The vocabulary recalls that of the Deuteronomic re-form. It would seem that the reform lost its effectiveness after Josiahís death and that under Jehoiakim many of the old syncretistic practices returned.

- Ezekiel 8. In a great vision Ezekiel visited the temple in Jerusalem and observed four of its abominations. Many of the details remain unclear, but he seems to have seen: (1) an altar outside the temple itself (an explicit violation of Deuteronomyís law of centralization), which threatened to drive Yahweh far from his sanctuary (8:3, 5-6); (2) a secret rite in a dark room, perhaps representing the cult of the dead, associated with Osiris (8:7-13);12 (3) women weeping for the Sumero-Babylonian vegetation deity Tammuz or Dumuzi (8:14-15); (4) twenty-five men worshiping the sun right at the door of the temple.

Jeremiah mentions no such abominations in the post-Josian temple. Did Ezekiel base his critique on the sins actually being committed in his day, or has he selected sins from various eras of Israelís history to characterize their utter rejection of God? Such a telescoping of Israelís sin history might account for his catalog of sins in chap. 6 as well.

- Ezekiel 15. The only specific offense mentioned in this chapter is Israelís faithless actions (v. 8). More important is the way in which Ezekiel characterizes the people as lacking any worth. He compares them to the "wood" of a grapevine which has no value for the carpenter even when it is whole. How much less when it is burned and charred! Israelís general claim to value before God is denied; its specific status after the first deportation of 597 is only that of potential fuel for more fire.

- Ezekiel 16 and 23. These chapters compare Jerusalemís or Israelís behavior to that of adulterous women (cf. Hos. 1-3; Jer2:2-3; 3:6-14). According to chap. 16, Jerusalem was bad from the beginning. Her father was an Amorite, her mother a Hittite, apparently the prophets theological interpretation of the cityís late incorporation into Israel. Despite Yahwehís loving care, Jerusalem played the harlot, both by consorting with other gods and, at least according to the present text, by associating with other nations-Egypt, Philistia, Assyria, and Chaldea. Jerusalem is a harlot who pays her customers, an ironic allusion to the tribute she had dispatched to foreign powers. Jerusalem is worse than

- Cf. W. F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1953), pp.166-67.

Samaria, which fell in 721; aye, she is worse even than Sodom, whose people failed to help the poor and needy. In comparison with Jerusalem, Samaria and Sodom appear righteous!

Chap. 23 continues the accusation of spiritual harlotry, but now it is used to describe two sisters, Oholah and Oholibah, standing respectively for Samaria and Jerusalem, the capitals of the northern and southern kingdoms. The southern kingdom is depicted as being much worse than the northern, especially in her running from one foreign lover (ally) to another. She flitted from the Assyrians (vv. 12-13) to the Babylonians (vv. 14-18), only to pick up with the Egyptians (vv. 19-21). Behind this last accusation we should see a criticism of Jerusalemís vain alliances with Egypt in her final days. Such harlotry, says Ezekiel, is what she did in Egypt already before the Exodus.

- Ezekiel 20. In response to an inquiry brought by the elders of Israel before the final fall of Jerusalem, Ezekiel told a negative .,salvation history" in three phases that fully justified Yahweh's brusque rejection of the inquiry in v. 31. Israel had benefited from Godís gracious acts and received instructions or laws from God in each of the three phases, but she acted rebelliously against him and called forth his wrath. Nevertheless, Yahweh acted repeatedly for the sake of his name, lest it be profaned among the nations, and he did not pour out his wrath.

The cause for all these severe judgments is solely Israelís. Neither the period in Egypt nor the one in the wilderness (per contra Hosea and Jeremiah) was the "good old days." Israel was rebellious right from the start in Egypt. There never had been a time of faithfulness. So deeply rooted is the peopleís sin that their behavior in the land is irrelevant-one way or the other-to the question of the onrushing judgment 13. Since the present generation doggedly repeats the sins of the fathers, their inquiry is rejected outright.

Why must the end come? Despite his long and at times verbose telling of Israelís faults (cf. also 22:1-16, 23-31), Ezekiel seems

- The history of Israel in the land, vv. 27-29, is the contribution of a later hand.

to be at a distance from the day-to-day events of Jerusalemís last six years. We have no sure way of telling how many of the specific charges are plausible, but his main point was that the guilt for all of Israelís history would come to a head in the present generation. Israelís history lacked any period in which righteous-ness prevailed. From the stay in Egypt until his own day, the prophet sees nothing but abominations, detestable things, idols, and harlotry.

JUDGMENT ON THE NATIONS

The Book of Ezekiel contains words against seven nations in chaps. 25-32, and a further oracle against Edom in chap. 35. Despite disagreements, now as before, over which of these oracles comes from the prophet himself, a number of observations can be made on the present text that help us understand Israelís reaction to exile. It is doubtful that any of these oracles can be dated later than the sixth century.

- Tyre is rebuked for its pride (28:1-10), especially for its pride in its beauty (27:3; 28:17); for its violence (28:16); and for the unrighteousness of its trade (28:18). The prophet also scores Tyre for rejoicing over Jerusalemís fall (26:2).

- Ammon, Moab, Edom, and Philistia are similarly criticized for celebrating the profanation of Godís sanctuary and the fall of Judah, and for sharing in the plundering of the land. The judgment on Israel had stemmed from Godís righteous decision; it should not be the occasion for self-aggrandizement or territorial expansion by others.

- The oracles against Egypt criticize it for its useless offers of support for Judah in the final years and for the disastrous false trust this evoked from Israel (29:6.-7). Egyptís pride (29:3, 9), its arrogance as a superpower (31:3ff.), and its violence (32:32) have earned it total annihilation at the hands of Babylon.

- The word of demonstration form (Erweiswort) abounds in the oracles against the nations. Thus, the punishment of the nations is seen not as an end in itself or even merely as retribution for the sins mentioned in paragraphs 2-3 above. Rather, the seven foreign nations will come to know and acknowledge through their experiences of judgment the God who says "I am Yahweh." Such an acknowledgment by the nations is the goal also of Godís saving acts for Israel (e.g. Ezek. 36:23; 37:28).

- The destruction of the nations is the beginning of Israelís salvation. No longer will these nations hurt Israel (28:24). Their defeat, in fact, will be followed by Israelís renewed dwelling in the land (28:25) or the exaltation of Israelís power (= its horn, 29:21). Through the events connected with the defeat of the na-tions, Israel too "will know that I am Yahweh" (e.g. 28:24, 26).

A NEW EXODUS: GODíS YES TO ISRAEL

Like the D redaction of Jeremiah and like Second Isaiah, Ezekiel foresaw a new exodus as Godís way of remaining faithful to the promise inherent in the first exodus. The most extensive treatment of this motif appears in a disputation word at 20:32-44 that has been placed at the end of the pericope rejecting the eldersí inquiry (20:1-31).14 The passage begins with the peopleís expression of defeat and hopelessness. If Godís judgment is inescapable since his decision on exile had been reached before Israel entered the land under Joshua, why not live among the nations in peace and serve their idols (v. 32)? Yahweh replied with an oath: "As I live, says Lord Yahweh, surely with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, and with wrath poured out, I will be king over you. I will bring you out from the peoples and gather you out of the countries where you are scattered" (vv. 33-34).

Godís kingship meant that he would bring a new exodus (cf. Exod. 15:18), surely a promise that was not easily believable early in the Exile. Yahweh had to argue for it by invoking a curse on himself ("as I live . . ."). His kingship could be inaugurated only by a power display against the enemy. In addition, his wrath would be poured out, according to Ezekiel, on the rebels and transgressors within exilic Israel (v. 38; cf. v. 8, 13, 21). That is,

- See Zimmerli, "Der Ďneue Exodusí in der Verkündigung der beiden grossen Exilspropheten," Gottes Offenbarung, pp. 192-204, Cf Baltzer, Ezechiel und Deuterojesaia, pp. 2-11.

not everyone who would experience the new exodus would be allowed to go on to Zion. Instead, the exodus would commence from many countries (v. 34), and it would lead to a judgmental confrontation between Yahweh and Israel in the "wilderness of the peoples" (v. 35). Yahweh would be Israelís judge (v. 36) as he had judged and purified Israel during its first desert wandering. Like a shepherd he would make all sheep pass under his staff, with the result that only a few and then only those who did not rebel or transgress (v. 38) would enter the land of Israel (cf. 34:17-19 and Matt. 25:31-46).

The goal of this new exodus is a procession to Zion, not merely a retaking of the land (v. 40). Attainment of this goal will demonstrate Godís holiness, his godhead, for all the nations to see (v. 41). The gift of the land itself (v. 42; cf. 11:17-18; 34:13;36:24; 37:21) will be the fulfillment of the old promise to the fathers, and it will lead to a double insight: (1) the people will know and acknowledge that their God is that Yahweh whose identity was disclosed at the time of the first exodus (v. 42: cf. Exod. 3 and 6); and (2) they will be led to recognize their own shameful behavior when they see the great deeds of Godís kind-ness (v. 43).", The only reason why exilic Israel can know God is that Yahweh acts for his own nameís sake and not according to their own corrupt doings (v. 44). That name, or reputation, was slandered when Israel went into captivity among the nations (36:22). Now Yahweh must save his own reputation-that is, he must vindicate his holiness-by rescuing Israel (36:23; cf. 39:25). Israelís miserable condition is not the reason why Yahweh chooses to act (36:22-23).

In sum, the new exodus for Ezekiel presents the faithful God acting freely, that is, in a way appropriate to the new situation of exile. The prophetís stern picture of God as king, judge, and shepherd reminded his contemporaries of their accountability for the Exileís judgment. Yet Ezekielís Yahweh also counteracts

- CE 6:8-10; 16:54, 62-63. Similarly, the new temple will make Israel re-member with shame her former iniquities (43: 10-1 1).

the despair of the people by promising military action against their foes and by invoking self-imprecations to support his own words. By manifesting his holiness Yahweh will produce a purified remnant as a witness to the nations. On his holy mountain, toward which the exiles freed from Babylon process, Yahweh will accept his repentant people and receive from them their faithful and abundant offerings.

THE GOOD SHEPHERD

Chap. 34 begins with a woe oracle against the shepherds or rulers of Israel, who have only cared for themselves and not for the flock (people) entrusted to them. They have not fed the sheep, strengthened the weak, healed the sick, bound up the crippled, brought back the strayed, or sought the lost. Ruling violently, they turned their flock over to wild beasts. The unrighteous rulers, in short, are responsible for Israelís falling prey to the nations. The bottom line on this unit is a word of judgment against these rulers or shepherds (v. 10; cf. 17:11-21;19:1-9, 10-14; 21:25-27).

Yet the chapter goes on to describe how Yahweh himself will act as the good shepherd. He will seek out the lost sheep in exile and will bring them home to Palestine where he will feed the hungry and help all who are injured or oppressed. Later traditionalists (see especially vv. 23-24) modified this word by having Yahweh promise to rule through an earthly shepherd, a new David. The monergism of Godís action as shepherd presupposed in the original oracle, however, is the real strength of Ezekielís own solution to the problem of exile.

CREATION AND RESURRECTION

The theocentric emphasis is also well represented in the vision of the dry bones (37:1-14). In this vision the prophet saw a valley covered with bones that were both numerous and dry. This symbolism meant that many people had died and that they had been dead for a long time. Ezekiel was told to prophesy to these bones and tell them that Yahweh would supply them with sinews, flesh, and skin, and that then he would enliven them by giving them breath (v. 6). Clearly, the prophet understands the resurrection of these bones as a new creation; the parallels to Jís creation account (Gen. 2:7; cf. Eccles. 12:7) are unmistakable. A great theophanic noise accompanies the reassembly of the bones, and the enlivening spirit comes, at the prophetís invitation, to set the re-formed people on their feet as a mighty army. This vision is interpreted by vv. 11-14. The interpretation identified the bones with the whole house of Israel and cites three complaints of the people, which are then disputed: "Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are clean cut off" (v. II). Strangely, the metaphor soon changes from bones strewn on a battlefield to corpses lying in graves. While the metaphor in vv. 1-10 was primarily that of new creation, the miracle described in vv. 11-14 is more explicitly resurrection. In addition, the verb employed for "bringing up" from the graves is used elsewhere in the Bible to denote the Exodus (I Sam. 12:6; Hos. 12:14). This resurrection/exodus is to be followed by life in the land.

Several observations seem warranted:

- Radical, dependency on God for any future hope is the major theme of this passage. The very dryness of the bones and the peopleís complaints about their hopeless condition empha-size that no self-deliverance is possible. By describing the restoration of Israel as a creation, resurrection, exodus, or a new gift of the land, the prophet alludes to activities which by definition are solely the work of God. Furthermore, the "breath" is not merely the breath of life related in some way to the four winds (v. 9). It is the spirit that comes from Yahweh-"my spirit" (v. 14).

- New life in the land is not an end in itself. Rather, the en-livening of the enfleshed bones (v. 6) or the resurrection and subsequent gift of the land (vv. 13-14) have as their ultimate intention Israelís recognition and acknowledgment of Yahwehís true identity: "You shall know that I am Yahweh." This faith goal, this doxological intention, puts decisive checks on any merely nationalist understanding of salvation.

- The pericope ends with a powerful appeal to the word of God as the basis for hope: "I have spoken and I will do it, oracle of Yahweh" (v. 14, RWK). The hope conveyed by this vision is not just a possibility, one of many future scenarios. Israel can count on it, it is part of Godís word. The power that guarantees new life after exile is that creative word of God proclaimed by the prophet.

A future for Israel can only be understood under the category of life from death. The radicality of judgment and the radicality of Godís salvation could hardly be more sharply expressed. Israelís misery is not just its fate; it is also its guilt. Israelís future will happen without any self-help on her part, The vision of the dry bones expresses Godís unconditional promise for the future (but see 18:24).

THE SPECIFICS OF THE NEW AGE-A NEW COVENANT

In passages thought to be authentic Ezekiel does not frequently or unambiguously use the term covenant to describe preexilic Israelís relationship to Yahweh. His picture of future Israel, how-ever, includes an everlasting covenant of peace, and in this idea he shows both continuity and contrast with other exilic authors.

1. 34:25-30.(16) The new covenant described in these verses is called a covenant of peace, a promise of wholeness and prosperity. Wild animals will no longer disturb Israel (vv. 25, 28; cf. v.8),17 nor will enemy nations oppress, enslave, or reproach them(Vv. 27-29). In fact, Israel will dwell securely in the wilderness and sleep in the woods (vv. 25 and 27), and no one will intimidate them (v. 28). The covenantal peace will mean good rainfall, fruitful trees, abundant crops, and an end of hunger (vv. 26, 27,29; cf. 36:29-30, 34-35). A word of demonstration containing the covenant formula brings this pericope to its climax: "They shall

- This passage is one of a series of supplements to the description of Yahweh as good shepherd in vv. 1-16. While the words may come from the school of Ezekiel rather than from the prophet himself, they are hardly to be dated later than the end of the Exile. Cf. Zimmerli, Ezechiel, P. 847.

- Elsewhere in Ezekiel wild animals are agents of Godís punishment (5:17;14:I5,21; 33:27).

know that 1, Yahweh their God, am with them, and that they, the house of Israel, are my people" (v. 30). The detailed blessings of this new covenant display many verbal similarities to Lev. 26:3-13, but the blessings according to Leviticus are responses to human obedience; in Ezekielís monergistic theology they are free gifts of God. No reference is made in Ezekiel to any specific agricultural efforts; everything comes from Yahwehís hand.

- 37:26. "I will make with them a covenant of peace, an eternal covenant it will be, and I will multiply them." 18 Two comments need to be made on this passage. First, the new covenant includes the blessing of human fertility-good news for a people in exile and similar to the command/promise to be fruitful and multiply which we will study in P (chap. 6). Great population growth is also promised in 36:10-11, 33, 36, 37-38, where we read also of the restoration and rebuilding of the cities (cf. 28:26). Secondly, the covenant, though everlasting and connected with fertility as in P, is a new covenant, even if the word new is not explicitly used. Ezekiel does not rely on the covenants with Noah or Abraham (like P) or appeal to a return to Horeb/Sinai (like Deuteronomy; cf. Dtr). The new covenant he foretells has many similarities with the new or renewed Sinai covenant referred to in Jeremiah (31:31-34).

- 16:59-63.19 In this pericope Yahweh confirms that Jerusalem has broken the covenant and will experience punishment appropriate to her deeds. Yet, he promises to remember the earlier covenant (v. 60; cf. v. 8) made in the days of her youth, despite the fact that Jerusalem has persistently forgotten her faithful youth (vv. 22 and 43). When Yahweh remembers, he will establish an everlasting covenant, leading Jerusalem to know and acknowledge him. The giving of this covenant is linked with the forgiveness of

- For the text see BHS and Zimmerli, Ezechiel, p. 906.

- Vv. 44-59 deal with Jerusalem and her sisters rather than with Jerusalem herself as in vv. 1-43. Since vv. 59-63 build on vv. 44-58, they are not part of the original text, though there is no need to date them later than the end of the Exile.

sins, as in Jeremiah (v. 63). Since the broken covenant carried with it Godís curse, the promise of a new covenant might seem to trivialize Godís anger or make him appear inconsistent. Ezekiel, however, affirms the full depth of Israelís sin and holds to the necessity of Godís punishment. A new covenant is only possible theologically and logically by the interposition of Godís gracious forgiveness. Forgiveness also plays a role in Yahwehís promise to purify restored Israel: "I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean from all your uncleannesses, and from all your idols I will cleanse you" (36:25; cf. v. 33).

The new covenant will last forever. The corollary of this permanence is that the Israel of the restoration will be faithful and obedient. God will enable Israelís new obedience by inwardly transforming them: "A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you; and I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes and be careful to observe my ordinances" (36:26-27- cf. v. 29 and II: 19). Only Yahwehís actions and his forgiveness free Israel for service (cf. 34:22; 37:23).

The new covenant is part of Godís faithfulness to his earlier relationship with Israel, but it is also part of his gracious freedom in that (a) the covenant is made possible by his forgiveness, (b) it will result in a faithful Israel, and (c) it will last forever.

ONE NATION, ONE PRINCE-KING

Could there be an Israel without a Davidic king? Ezekiel had much to say against earlier princes of Israel (cf. 22:6, 25) and especially against Zedekiah, the last king (17:12ff.), but the promise to David remained for him, or at least for the members of his school who edited his work, part of the ongoing fidelity of Yahweh. Yet, Yahweh was free to modify the description and function of the royal office. The Book of Ezekiel includes restrictions on the future royal office, thus offering an implicit criticism of previous excesses, and gives it a far lesser role than the notion of the "presence of God" which is at the center of the prophet's picture of coming times .20 Though almost all the passages dealing with the future Davidide may be supplements to authentic oracles, none of them presupposes the later difficulties connected with the disappearance of Zerubbabel. A date between587 and 538--that is, in the Exile--seems probable for all of the following items.

- 17:22-24. In this supplement to vv. 1-21, Yahweh promises to take a piece from the top of the cedar and plant it on the high mountain of Israel. The cedar stands for the Davidic line, the high mountain for Zion. From this new tender plant will grow a gigantic tree in which all the creatures of the earth, both beasts and birds, will seek refuge. No specifics are given about the character of this coming ruler, nor are we informed about any of his activities. The whole point seems to be that all the trees of the field, that is, all nations, will recognize in this new act Yahweh at his characteristic best; he humbles the proud and exalts the lowly (cf. I Sam. 2:7; cf. Luke 2:52). The new monarch of the Davidic line will not inaugurate the new age by military strength. Rather, Yahweh alone brings new times whose peaceful character will redound to his own glory. The promise, in any case, is sure: "I have spoken and I will do it" (v. 24).

- 34:23-24. This messianic supplement promises that alongside Yahweh the good shepherd (vv. 11-16) there will be one earthly shepherd. The emphasis on the word one shows that the divided kingdom with its attendant evils will be a thing of the past. The new shepherd is to be called "my servant" and "David." Earlier prophets had identified the Messiah as a descendant of David (Isa. 9:6-7; Jer 23:5-6), and the use of the title David for him is not unknown elsewhere (Hos. 3:5; Jer 30:9-10). Yahweh explicates his relationship to the messiah in a modified covenant formula: "I Yahweh will be God for them; my servant David will be prince in their midst." The title prince may be an

- Godís gift of a new king/prince is never the rationale behind a word of demonstration, thus showing its less-than-central significance.

- Cf. Zimmerli, Ezechiel, p. 1248. None of the words about the nasií in Ezek.40-48 can be dated prior to 571.

attempt to show the ancient roots of this office in Israel (cf. Exod. 22:7), or it may be an implicit criticism of the pretensions of or the corruption of preexilic kingship.

- 37:22 and 24-28. After the vision of the valley of dry bones(vv. 1-14), chap. 37 contains an account of a symbolic act, promising the reunification of Israel (vv. 15-19). Israelís future is not to be plagued with the troubles of the divided kingdom. A supplement to this symbolic act in vv. 20-23 (24a) makes the reunification a product of the new exodus and the new gift of the land. just as there would no longer be two kingdoms, so there would no longer be two kings. The. promise of one king in v. 22 is only the corollary of a reunited Israel.

In the following pericope, vv. 24b-28, we are told of new Israelís obedience, and this is followed by four promises that will be everlasting-the land, the Davidic prince, the covenant, and Godís presence in the sanctuary. As we shall see, the last of these is of climactic importance. As to the Davidic prince who will last forever, it is important to note that his presence is almost incidental, and nothing specific is said about his function.

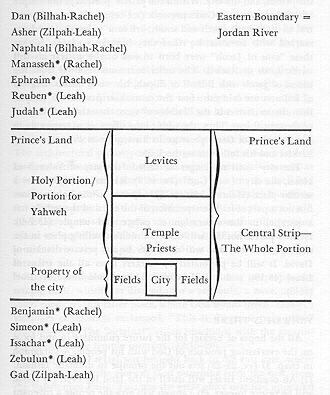

- 40-48. In these final chapters of Ezekiel reference to a prince (nasií) is made some twenty times, though perhaps none of these references comes from the original draft of the book. The prince will receive land (45:7; 48:21, 22) on either side of the territory assigned to the priests and Levites and on either side of the city (see diagram below). This will guarantee him income, but it is also meant as a polemic: never again will the kings appropriate the property of average citizens (45:8), an offense which the Deuteronomist had already seen as an ever-present danger (I Sam. 8:11-17a). This royal land will be inviolable (46:16-18), but by the same token the prince will not be able to violate the land of others under this arrangement. In addition to land, the prince will receive certain taxes (45:16)from which he is to provide the offerings for various feasts including the Passover (45:17, 22). The prince will perform his cultic duties in the east gate (44:3; 46:1-12) as a first among equals. He will be the most prominent member of the worshiping community, but a member of the community nevertheless, without explicit priestly functions. No rulership functions are assigned to him in 40-48.

THE LAND

Though Ezekiel contains little or nothing about a new conquest, the promise of the land frequently appears. By giving the land once more to Israel, Yahweh will remain faithful to his promises to the patriarchs, especially to Jacob (20:42; 28:25;37:25; 47:14). The land will be considered permanent just like the covenant and kingship. A broken covenant had led to loss of land and resultant exile. In the new, unbreakable possession of the land, no one will be able to make Israel afraid (e.g. 34:28), and the people will dwell on the land securely (e.g. 34:25). The promise of the land is made concrete in the descriptions of its extent and of its divisions (45:1-8; 47:13-48:29).22 Ezekielís placing of the eastern border along the Jordan River (47:18) may reflect the fact that the Transjordanian territories throughout their history had been more open to the suspicion of syncretism, idolatry, and apostasy. Excluding these territories from the promised land lessens the risk of any future falling-away.

The mapís division into twelve tribal allotments and a central sacred area symbolizes Godís saving intent; it is not a realistic blueprint. No irregularities of geography are taken into account in drawing the tribal boundaries, but each tribe is ascribed an equal portion (47:14). Perhaps we should see here a reaffirmation of the egalitarian principles of early Israel, according to which all things really belong to Yahweh and no one was to accumulate riches at the expense of his neighbor (Lev. 25:13, 23; cf. also Isa. 5:8 and Mic. 2:1-5). The reinstitution of the tribal divisions may be implicit criticism of Solomon, whose new administrative

- These sections come from later, though still exilic, bands. For detailed discussion see G. Ch. Macholz, "Noch Einmal: Planungen für den Wiederaufbau nach der Katastrophe von 587," VT, 19 (1969): 322-52; W. Zimmerli, "Planungen fiir den Wiederaufbau nach der Katastrophe von 587," VT 18 (1968): 229-55; and idem, "Ezechieltempel und Salomostadt," Hebräische Wortforschung VTSup 16 (1967): 398-414.

districts dispensed with the old tribal system (I Kings 4:7-19).The map of the new land of Israel can be diagramed as follows:

We note that Dan is still in the north, as in preexilic times Uudg.18:27; but cf. josh. 19:40-48), and that seven of the twelve tribes are north, of the central strip, thus approximating the greater size of the territory once known as the northern kingdom. In general, however, the organizing principle is quite different from the original land division. The land of Israel now finds its focus on the central strip within which are portions for the Levites, the priests, and the city. Within the priestsí portion is the temple with its guarantee of Godís presence (see below). Next to the central strip, to both north and south, are four tribes that we have marked with an asterisk. What they have in common is that these "sons of Jacob" were born to one of the patriarchís full wives, Leah or Rachel. The other four sons resulted from the union of Jacob with Bilhah or Zilpah, his wivesí maids. Degrees of holiness are laid out: first the central strip with the temple, then the territories of the "full-born" sons, then those of the sons of the concubines. Thus, the whole land offers silent testimony to the centrality of Godís presence in his temple as the response of Ezekiel and his followers to the Exile.

The City (23) will no longer be called "the city of Yahweh of Hosts, the city of our God" (Ps. 48:8). Rather, it has become a secular place (Hebrew hol, 48:15), adjacent to the holy portion, but not a part of it. The separation of the city and the temple has a parallel in the separation of palace and temple (43:7-9). Neither palace nor city will defile Yahwehís dwelling place in the new age. The city also will no longer be the private domain of David. It will be populated by workers from all the tribes of Israel (48:19), and it will belong to the whole house of Israel (45:6).

YAHWEH IS THERE

All the hopes of Ezekiel for the future culminate in and focus on the everlasting presence of God with his people. A paragraph in chap. 37 (vv. 25-28) sets out the promise in dramatic fashion: (1) An obedient Israel will dwell in the land for ever. (2) David will be prince forever. (3) Yahweh will give the people a covenant that lasts forever. (4) "I will set my sanctuary in their midst for ever. My dwelling place shall be with them; and I will be their God and they shall be my people. Then the nations shall know

- Obviously Jerusalem is intended, though the name itself is not used in 48-.15-19.

that I Yahweh sanctify Israel, when my sanctuary is in the midst of them for ever." The promise that Yahweh will dwell in the midst of his people is stated three times; twice it is underscored with the term for ever. Only this promise is connected with the covenant formula ("I will be their God and they shall be my people"). Only the fulfillment of this promise will cause the nations to acknowledge Yahweh.

Chaps. 40-42 contain Ezekielís vision of the new temple. (24) In the twenty-fifth year of his exile, (25) Ezekiel was brought to the land of Israel and was set down on a high mountain (40:2). Ezekiel saw three outer gates, located on the east, north, and south respectively, leading into the outer courtyard. Facing these gates were three more gates leading to the inner court (40:1-37). The architectural prototype of these gates has been discovered by modern archaeologists in tenth-century Solomonic contexts at Gezer, Megiddo, and Hazor. Presumably, Jerusalem also itself had such gates (cf. I Kings 9:15, 19). In any case, Ezekiel has transferred these gates from the city defenses to the temple area itself. Since there is no western gate, we might suppose that the prophet meant to render impossible the sin of 8:16-18. However one approached the new temple, he would not face the rising sun in the east.

Ezekiel was subsequently led through the inner court into the temple itself, which was divided into a vestibule, a nave, and an inner room. At this latter place, where God would dwell, Ezekielís visionary companion exclaimed, "This is the most holy place" (40:47-41:4). The "original" vision concluded with the measuring of the entire temple complex (42:15-20).

At this point Ezekiel was brought back to the east gate, where he saw and heard the glory of God returning from the east, from the Babylonian Exile. This was the same glory that had appeared

- Perhaps only 40:1-37; 40:47-41:4; and 42:15-20 are to be considered original. So Wevers; cf. Zimmerli.

- Zimmerli notes that the dimensions of the buildings in the temple vision are all multiples of twenty-five. He suggests that this number twenty-five reflects the twenty-fifth year of the date formula and that the twenty-fifth year would make the halfway point of a jubilee period when a release could be expected.

at his call (chaps. 1-3) and at his vision of Jerusalemís destruction (chaps. 8-11). This glory reentered through the east gate and filled the temple (43:1-5). The east gate, through which the glory had passed, was then permanently closed (44:1-2). No one would ever again step on the holy path by which Yahweh had returned. With the gate permanently closed, Yahwehís presence could also be considered permanent.

What would Godís presence mean for Israel? Ezekielís guide took him back to the door of the temple, and there he saw water flowing from the temple toward the east. At first it was only ankle deep, but it grew gradually deeper until one could only swim in it; it had become too deep for walking (47:1-6). Along the banks of this river were trees which bore fresh fruit every month. When the river emptied into the Dead Sea it made the briny waters fresh, and fish abounded even in the (formerly) Dead Sea (47:7-12). The meaning of this passage becomes clear when it is studied against the background of ancient Near Eastern and Old Testament tradition. The Canaanite god El had his dwelling at the meeting place of two rivers, and the Old Testament also frequently associates water with Yahwehís dwelling place (Gení 2:10-14; Ps. 46:4; cf. Isa. 8:5-8). Hence, Ezekielís description of a stream at Godís dwelling place is in itself no surprise. But his stream represents also the marvelous transforming powers of Godís presence: it brings to life the infertile Judean wilderness and even gives life to that sea whose very name is the epitome of all lifelessness. Godís presence, in short, brings about a new creation of the land. When later hands added the description of the extent and divisions of the land in 47:13-48:29, they described a land that was healed by Godís presence. All former dangers and iniquities were done away by Godís presence: its zones of holiness pointed to the importance of Godís temple presence with a kind of silent praise.

Whoever was responsible for the final pericope in the book(48:30-35) also wanted to testify to the importance of Godís presence. He differed from the tradents responsible for the land division pericope (47:13-48:29) in that the twelve tribal names he gave to Jerusalemís gates included the tribe of Levi and consequently combined Ephraim and Manasseh in their father Joseph. He differed from Ezekiel in that he restored Jerusalem itself to its old religious importance as the dwelling place of God, but he echoed Ezekielís own theological response to exile when he wrote, "And the name of that city henceforth shall be, ĎYahweh is thereí " (48:35). The cityís name proclaims the heartbeat of this priestly-prophetic theology. Godís presence legitimated Ezekielís call and provided a measure of comfort for the exiles themselves (11:16). Godís reentry and permanent dwelling in the midst of the people would take place only by virtue of his own gracious decision-and it would make all things new and alive.

CALLED TO BE A WATCHMAN

The Book of Ezekiel contains a second call of the prophet (3:16b-21; 33:1-9) in which he is assigned the dangerous task of watchman: He is to warn people about their wickedness. If they listen to him, well and good; if they donít listen to him, they will die, but Ezekiel will be exonerated; if Ezekiel fails to warn them and they die, their blood is laid at the prophetís door. After 587, when this office of watchman took effect, Ezekiel was no longer to preach the unconditional judgment of God, but he was to be Godís helper in saving the people. Each individual in Israel was now his audience; he told them what it was necessary to do now. Some in his audience might have cynically claimed that their evil behavior was due to a propensity toward sin inherited from their fathers (18:2-20; cf. Ezek. 16, 20, 23). Yet no one could claim that his fate is fixed by his relativeís behavior. (18:20). Others might have felt trapped in the behavior-pattern established in the earlier part of their own lives (19-21-32; 33-10-20). Individuals from both groups are urged by Ezekiel to turn and to live. Those who turn from their evil deeds will be granted the joys of Godís presence. That is what seems to be meant by Ezekielís offer of "life" (18:9, 17, 32). On the other hand, those who persist in doing evil will be denied access to Godís presence; they will die (18:13).

The promised future in Ezekiel is solely the product of Godís monergistic actions. Yet in the new age obedience will be expected, and even now, while the people still wait for the new day, they are urged to repent. Life is offered, but something more is expected from the people than a lazy, complacent, lifeless waiting for God to do it all. That "something more" is that even now the people commit themselves to do Godís will. Ezekielís role as watchman and his call for people to turn right now reflect a creative tension found also in the message of Second Isaiah. A faith clinging to the rays of Godís dawning future must be a faith active in obedience and love.

EZEKIELíS MESSAGE OF HOPE

Because of the peopleís total corruption, Ezekiel neither announced nor desired any escape for Israel from Nebuchadnezzarís sword. Yet his words after 587 abound with hope. Yahweh would effect a new exodus followed by a return to Jerusalem, he would be a good shepherd, and he would bring life to an Israel dead in exile. This life could be described as an everlasting covenant, marked by Israelís obedience and by abundant fertility in nature and among the people. Israel would again have a prince like David and would possess the land. Central to all Ezekielís promises, however, was Godís permanent dwelling with his people. To express this promise, the prophet (or his followers) painted a picture of the land arranged in symbolic zones of holiness radiating from Godís presence in the temple. A stream from that temple would bring about a new creation, including fertility to the barren wastes of the Judean wilderness and life to the Dead Sea. Ezekiel called his audience to repentance and assured them that nothing--not even unfulfilled threats of invading enemies from the north (cf. the defeat of Gog in Ezek. 38-39)--could ever disturb their security.

Ezekiel believed that God would be faithful to his old promises and that God was free to act beyond judgment and in creative ways. Part of Godís creativity would manifest itself in pro-visions designed to protect future Israel from all dangers and temptations. Part of his creative freedom was the way in which he would make new Israel simply surpass the old. But the ultimate goal of all this faithfulness and freedom was to bring about a universal "knowledge." Ezekiel anticipated a time when even the nations would acknowledge and confess the one God: "Then the nations will know that I am Yahweh."