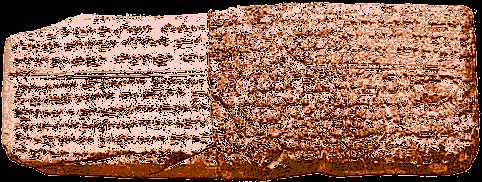

Do you recognize this?

Chances are you don’t. That’s okay;

it’s not exactly that famous. But if you do, you are to be congratulated for

identifying the earliest surviving complete piece of written music, generally

called “Hurrian Hymn no. 6”.

More or less complete, at least –

it’s broken in half, and one of the halves is crumbling (fired clay tablets

don’t exactly react well to water). It’s not surprising that it’s in such bad

shape: it’s about 3200 years old. It was found in the ruins of the city of

Ugarit, near the modern town of Ras Shamra (Cape Fennel), Syria.

Although the tablet has seen better

days, enough of the cuneiform signs written on it can be read to allow a rough

transcription into the Latin alphabet. Two transcriptions were made from the

original in the 1960s; some of the surface of the damaged half of the tablet

has since flaked off. The first transcription by E. Laroche, provides the groundwork

for Kilmer and Marcelle-Guillemin’s versions. The second, a (relatively) more

recent one by M. Dietrich and O. Loretz based on 1960s photographs of the

tablet taken from several angles, is more complete, and is used in the versions

by Thiel and Krispijn.

Enough can be read from what remains

to create a more-or-less comprehensive version of the text. Even so, there are

enough differences between the transliterations that I’ve opted to show six

variants:

|

Laroche |

[X-X] |

ḫa-nu?-ta |

ni-ya-ša |

zi-ú-e |

š[i?]-nu-te |

zu-tu-ri-ya |

ú-pu-X-ra |

[X-X-X-]-ur-ni |

ta-ša-al |

ki-il-[l]a |

[z]i?-li |

ši-i[p?-X] |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-ri |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kilmer |

[x (x)] |

ḫan[u]ta |

niyaša |

ziwe |

š[i]nute |

˹zutu˺riya |

ubugara |

˹kud˺urni |

tašal |

killa |

[z]ili |

šipri |

ḫumaruḫat |

uwa[ri] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Duchesne-Guillemin |

[xxx] |

-ḫanuta |

niyaša |

ziwe |

šinute |

zuturiya |

ubugara |

ḫuburni |

tašal |

killa |

zili |

šipri |

(ḫumaruḫat |

uwari) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dietrich &

Loretz |

[XXX] |

ḫa-aš-ta |

ni-ia-ša |

zi-ú-e |

ši-nu-te |

zu-tu-ri-ia |

ú-pu-ga-ra |

at?/ak??-ḫu-ur-ni |

ta-ša-al |

ki-il-[l]a |

mu-li |

ši-ip-ri |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-r[i] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Thiel |

[XXX] |

ḫa-aš-ta |

ni-ya-ša |

zi-ú-e |

ši-nu-te |

zu-tu-ri-ya |

ú-pu-ga-ra |

at?/ak??-ḫu-ur-ni |

ta-ša-al |

ki-il-[l]a |

mu-li |

ši-ip-ri |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-r[i] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Krispijn |

[x-a-aš]-ḫa-aš-ta-ni-ya-ša |

zi-ú-e |

ši-nu-te |

zu-tu-ri-ya |

ú-pu-ga-ra-ra |

at/ak-ḫu-ur-ni |

ta-ša-al |

ki-il-la |

mu-li |

ši-ip-ri |

(ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-ri) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-ri |

wa-an-da-[n]i-ta |

ú?-ku-ri |

ku-ur-ku-ur-ta |

i-ša-al-la |

ú-la-li |

kab-gi |

a[l]-li-X-gi |

ši-ri-it? |

X-[X]-nu-šu |

wə-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti-ši-a |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

ḫumaruḫat |

uwari |

wanda[n]ita |

ukuri |

kurkurta |

išalla |

ulali |

kabgili |

a[l]li[x]gi |

širit |

[mur?]nušu |

wešal |

tatib |

tišiya |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

ḫumaruḫat |

uwari |

wandanita |

ukuri |

kurkurta |

išalla |

ulali |

kabgili |

alligi |

širit |

[xx]-nušu |

(wešal |

tatib |

tišiya) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-ri |

wa-an-da-ni-ta |

ú-ku-ri |

ku-ur-ku-ur-ta |

i-ša-al-la |

ú-la-li |

kab-gi |

ú-li-ú-gi |

ši-ir-it |

ú?-nu-šu |

wa-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti-ši-a |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-ri |

wa-an-da-ni-ta |

ú-ku-ri |

ku-ur-ku-ur-ta |

i-ša-al-la |

ú-la-li |

kab-gi |

ú-li-ú-gi |

ši-ir-it |

ú?-nu-šu |

wa-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti-ši-a |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at |

ú-wa-ri |

wa-an-da-ni-ta |

ú-ku-ri |

ku-ur-ku-ur-ta |

i-ša-al-la |

ú-la-li |

kab-gi |

ú-li-ú-gi |

ši-ir-it |

ú?-nu-šu |

(we-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti-ši-a) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

wə-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti4-ši-a |

ú-nu-[g]a? |

kap-ši-li |

ú-nu-ga?-at |

ak-li |

ša-am-ša-am-me-X- -li-il |

uk-la-al |

tu-nu-ni-ta-X |

[X-X]-ka |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

wešal |

tatib |

tišia |

unu[g]a |

kabšili |

unugat |

akli |

šamšam |

me[x]- lil |

uklal |

tununita˹ka?˺ |

[ḫanu?]ka |

kalitanil |

nikala |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

wešal |

tatib |

tišia |

unuga |

kabšili |

unugat |

akli |

šamšamme |

[x]-lil |

uklal |

tununita |

[xxx]-ka |

(kalitanil |

nikala) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

wa-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti4-ši-a |

ú-nu-ul |

kab-ši-li |

ú-nu-ul-at |

ak-li |

ša-am-ša-am-me-ni |

ta-li-il |

uk-la-al |

tu-nu-ni-ta |

sa?-X-X-X-X-ka |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

wa-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

ti4-ši-a |

ú-nu-ul |

kab-ši-li |

ú-nu-ul-al |

ak-li |

ša-am-ša-am-me-en-ga-li-il |

uk-la-al |

tu-nu-ni-ta |

sa?-X-X-X-X-ka |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

we-ša-al |

ta-ti-ib |

di-ši-ya |

ú-nu-ul |

kab-ši-li |

ú-nu-ul-al |

ak-li |

ša-am-ša-am-me-ni |

ta-li-il |

uk-la-al |

tu-nu-ni-ta |

sa?-x-x-x-x-ka |

(ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

ni-ḫ[u?-r]a?-ša-al |

ḫa-na |

ḫa-nu-te-ti |

at-ta-ya-aš-ta-al? |

a-tar-ri |

ḫu-e-ti |

ḫa-nu-ka |

[ -a]š-ša-a-ti |

we-e-wə |

ḫa-nu-ku |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

kalitanil |

nikala |

ni[hura?]šal |

ḫana |

ḫanuteti |

attayaštal |

attari |

ta(?)eti |

ḫanuka |

[xxxxxxxx]-šati |

wewe |

ḫanuku |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

kalitanil |

nikala |

nihurašal |

ḫana |

ḫanuteti |

attayaštal |

attari |

ḫueti |

ḫanuka |

[xxxxxxx]-aš |

šati |

wewe |

ḫanuku |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

ni-ḫ[u]-r[a]-ša-al |

ḫa-na |

ḫa-nu-te-ti |

at-ta-ia-aš-ta-al |

a-tar-ri |

ḫu-e-ti |

ḫa-nu-ka |

X-zu?-[X-X-X-a]š?-ša-a-ti |

we-e-we |

ḫa-nu-ku |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

ni-ḫ[u]-r[a]-ša-al |

ḫa-na |

ḫa-nu-te-ti |

at-ta-ya aš-ta-al |

a-tar-ri |

ḫu-e-ti |

ḫa-nu-ka |

X-zu?-[X-X-X-a]š?-ša-a-ti |

we-e-we |

ḫa-nu-ku |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

ka-li-ta-ni-il |

ni-ka-la |

ni-ḫ[u]-r[a]-ša-al |

ḫa-na |

ḫa-nu-te-ti |

at-ta-ya-aš-ta-al |

a-tar-ri |

ḫu-e-ti |

ḫa-nu-ka |

X-zu |

[x-x-x-a]š-ša-a-ti |

we-e-we |

ḫa-nu-ku |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

kab-li-te |

3 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

kab-li-te |

2? |

X-X-X |

[ti]-ti-mi-šar-te |

10 |

uš-ta-ma-a-ri |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

qablite |

3 |

irbute |

1 |

qablite |

3 |

˹ša? šini?˺ |

titimišarte |

10 |

uštamari |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

kablite |

3 |

irbute |

1 |

kablite |

3 |

[ešgi] |

titimišarte |

10 |

uštamari |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

qáb-li-te |

3 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

qáb-li-te |

3 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

i-šar-te |

10 |

uš-ta-ma-ari |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

qáb-li-te |

3 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

qáb-li-te |

3 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

i-šar-te |

10 |

uš-ta-ma a-ri |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

kab-li-te |

3 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

kab-li-te |

3 |

ša-aḫ-re |

1 |

i-šar-te |

10 |

uš-ta-ma-a-re |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

ti-ti-mi-šar-ta |

2 |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-[a]ḫ-ri |

2 |

X-X-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

titimišarte |

2 |

zirte |

1 |

šaḫri |

2 |

zi[rt]te |

2 |

irbute |

2? |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

titimišarte |

2 |

zirte |

1 |

šaaḫri |

2 |

zirt]te |

2 |

šaššate |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

2 |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-[a]ḫ-ri |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

2 |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-[a]ḫ-ri |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

2 |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-[a]ḫ-re |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

tup-pu-nu |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-ta |

2 |

irbute |

X |

[š]a-[aš-š]a-t[e] |

X |

ti-tar-kab-li |

1 |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

umbube |

1 |

šaššate |

2 |

irbute |

[1] |

ša[šš]ate |

2? |

titarqabli |

1 |

titimišarte |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

embube |

1 |

šaššate |

2 |

irbute |

1 |

šaššate |

1 |

titarqabli |

1 |

titim išarte |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

um-bu-be |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

1[+X] |

na-ad-qáb-li |

1 |

ti-tar-qáb-li |

1 |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

um-bu-be |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

1[+X] |

na-ad-qáb-li |

1 |

ti-tar-qáb-li |

1 |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

um-bu-be |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

1+[x] |

na-ad-kab-le |

1 |

ti-tar-kab-le |

1 |

ti-ti-mi-šar-te |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

zi-it-te |

1 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-t[e] |

4 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

na-at-kab-li |

1 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

[1] |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

zirte |

1 |

šaḫri |

2 |

šaššate |

4 |

irbute |

1 |

nadqabli |

1 |

šaḫri |

[2?] |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

zirte |

1 |

šaaḫri |

2 |

šaššate |

4 |

irbute |

1 |

naatqabli |

1 |

šaaḫri |

1 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

na-ad-qáb-li |

1 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

na-ad-qáb-li |

1 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

zi-ir-te |

1 |

ša-aḫ-re |

2 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ir-bu-te |

1 |

na-ad-kab-le |

1 |

ša-aḫ-re |

1 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

ša-aš-š[a-t]e |

2 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-[b]u-[te] |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

šaššate |

4? |

šaḫri |

1 |

šašš[at]e |

2 |

šaḫri |

1 |

šaššate |

2 |

irbute |

2? |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

šaššate |

4 |

šaaḫri |

1 |

šaššate |

2 |

šaaḫri |

1 |

šaššate |

2 |

irbute |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ša-aḫ-ri |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

ša-aš-ša-te |

4 |

ša-aḫ-re |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ša-aḫ-re |

1 |

ša-aš-ša-te |

2 |

ir-bu-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

ki-it-me |

2 |

kab-li-te |

3 |

ki-it-[me] |

1 |

kab-li-te |

4 |

ki-it-me |

1 |

kab-li-te |

5? |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ki |

kitme |

2 |

qablite |

3 |

kit[me] |

1 |

qablite |

4 |

kitme |

1 |

qablite |

3?

[xxx(x)] |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D-G |

kitme |

2 |

kablite |

3 |

kitme |

1 |

kablite |

4 |

kitme |

1 |

qablite |

3 or 5 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

D&L |

ki-it-me |

2 |

qáb-li-te |

3 |

ki-it-m[e] |

1 |

qáb-li-te |

4 |

ki-it-me |

1 |

qáb-li-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

ki-it-me |

2 |

qáb-li-te |

3 |

ki-it-m[e] |

1 |

qáb-li-te |

4 |

ki-it-me |

1 |

qáb-li-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kr |

ki-it-me |

2 |

kab-li-te |

3 |

ki-it-m[e] |

1 |

kab-li-te |

4 |

ki-it-me |

1 |

kab-li-te |

2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L |

[an-nu]-ú |

za-am-ma-aš-ša |

ni-it-kib-li |

za-[lu-zi |

|

|

|

|

]ŠU |

mAm-mu-ra-bi |

|

Ki |

[ann]ű |

zammaru |

nidqibli |

za[luzi |

ša |

DINGIR.MEŠ |

TA |

mUrḫiya] |

ŠU |

mAmmu-rapi |

|

D&L |

[an-nu]-ú |

za-am-ma-rum |

ša ni-id-qib-li |

za-l[u]-z[i |

|

|

|

|

]ŠU |

mAm-mu-ra-bi |

|

Kr |

[an-nu]-ú |

za-am-ma-rum |

ša ni-id-kib-li |

za-l[u]-z[i |

|

|

|

|

]šu |

Iam-mu-ra-bi |

Unfortunately, when it comes to the meaning

of the lyrics and the reading of the music, consensus is hard to find.

Three attempted translations exist.

The first of these was made by the same man who made the first transcription of

the tablet, Émil Laroche. However, it barely qualifies as a translation, as

only a handful of words are translated:

humaruhat

= some kind of metal

wandanita

= “to the right”.

išalla

= from išaš “me”.

weš

= "thou"

tatib

= "thou lovest"

tišia

= from tiš- "heart" (thus

"Thou, thou lovest them in the heart")

šamšamme-

= "sesame"?

nikala

= Nikkal

ḫana,

ḫanuteti, ḫanuka, ḫanuku

= from ḫan- "give

birth"

we-e-wə

= of you

In his credit, he wrote this in the

1960s, when much less was known about Hurrian, and he made the (probably)

accurate assumption that “these lines have the appearance of a hymn or prayer.”

The second translation, from an

article written in 1977 by Hans-Jochen Thiel, is far more thorough, and uses a

transcription done by M. Dietrich and O. Loretz from 1975. Unfortunately, the

article is in German, which I only half-understand. Therefore, I will give the

translation in its original language:

Im Blei-Zustand1 will ich

… en (,)

zum rechten Fuss (des göttlichen

Thrones) (,)

ich … -e2; ich will sie

(Sündhaftigkeiten) ‘ändern’3

(Wenn die Sündhaftigkeiten) nicht

(mehr) ‘verdeckt’4 (sind) und wenn nicht (mehr) ‘geändert’ werden

muss, befinde ich mich wohl, fertig geopfert habend.

(Wenn ich die Gottheit) zu meinem

Gunsten (mit Opfern) besandt, würde sie (mich) in ihrem Herzen lieben;

zu meinem Gunsten (Opfer)

hingebracht, (so) möge es gänzlich ‘verdeckt’4 sein;

ich zu meinem Gunsten (Opfer)

hinbringend, (nämlich) Sesam-Öl mögen sie (als Opfer) hin führen;

ich mich fürchtend (,) möge … -en5

(,) nicht … -end.

Unfruchtbare(s) mögen sie fruchtbar

sein lassen,

Getreide mögen sie erzeugen,

sie wird sie (die Kinder) gebären,

seine Frau dem Vater (,)

möge …-en6 (,) wird

nehmen (die noch) nicht Geboren habende7.

1 ‘Blei’ in der

Eigentschaft einer (rituell) verwendeten Reinigungs-Substanz.

2 Wohl ein Verb

der Bedeutung des rituellen Reinigens bzw. Segnens.

3 ‘ändern’, i.e.

magisch-rituell ‘lösen’.

4

‘Nicht-Verdecktes’ mit dem Gegensatz ‘verdeckt’ in Zusammenhang mit einer

(religiösen) sündhaften Verfehlung.

5 Oder ‘werde

…-en’ bzw. ‘zu dem Götterschemel’

6 Oder ein Nomen

(‘Kind’?).

7 Oder ‘wird

entbeten’/

8 Oder ‘(das

noch) Ungeborene’. Also wohl entweder ‘(die noch) Nicht-Geboren-Habende wird

(ein Kind) …’ oder ‘(der Vater) wird das (noch) Ungeborene nehmen’.

The third translation, by Theo J. H.

Krispijn, was published much more recently, in 2000. Krispijn bases his version

on Thiel’s translation, but points out that the extensive material published

about Hurrian since 1977 has “substantially” increased our understanding of the

language.

This is without a doubt the best translation

of the three. Why? Well, for one thing, Krispijn’s translation is accompanied

by a transcription of the text which reflects the modern understanding of what

Hurrian really sounded like (its phonology). Thiel only tried this with a

handful of words. Far more impressive, however, is what follows the

transcription: a careful translation and grammatical explanation of each word.

Laroche tried this over three decades earlier, but, again, only with a handful

of words

While this article is in German, a

more recent article from 2008 gives his translation in English. I’ll give you

the best of both worlds: the Hurrian transcription of the 2000 article and the

English translation of the 2008 article. (Just as a side note, the Hurrian

transcription reads more or less like English in terms of the sounds of the

letters, and “ḫ” is pronounced

like the German “Bach”. I’ve replaced Krispijn’s “v”, “w” and “c” with

with their English phonetic equivalents “f”, “v” and “ts”. “x”, as always,

stands for an illegible or broken part of the tablet, not for the “ks” sound).

x asḫastaniyaza

tsive sinute tsuturiye ubugarat

(ḫumaroḫat uveri) ḫumaroḫat

uveri fandanita kre kurkurta

izalla ulali kapki ulifki sret unozo

(fezal tadiv tiziya) fezal tadiv

tiziya unol kapsile

unolt agli samsammeni talil uglal

tunonida tsa-x-x-x-x-ka

(kaledanil Nikalla) kaledanil

Nikalla niḫrazal ḫana ḫanodedi atayastal

adarre ḫowedi ḫanoka x-zu x-x-x-asati feve ḫanoko

For the ones that are offering to

you (?)

prepare two offering loaves in their

bowls, when I am making a sacrifice in front of it.

They have lifted sacrifices up to

heaven for (their) welfare and fortune (?).

At the silver sword symbol at the

right side (of your throne) I have offered them.

I will nullify them (the sins).

Without covering or denying them (the sins), I will bring them (to you), in

order to be agreeable (to you).

You love those who come in order to

be covered (reconciled).

I have come to put them in front of

you and to take them away through a reconciliation ritual. I will honour you

and at (your) footstool not....

It is Nikkal, who will strengthen

them. She let the married couples have children.

She let them be borne to their

fathers.

But the begetter will cry out:

"She has not born any child!" Why have not I as a (true) wife born

children for you?"

For anyone interested in seeing his

word-for-word translation (in German), click the following links: Krispijn

Page 1 Krispijn

Page 2

WARNING:

THE FOLLOWING SECTION CONTAINS MUSICAL TECHNOBABBLE. IF YOU’RE HERE FOR THE

MUSIC, SKIP THIS SECTION – BUT AT YOUR OWN PERIL.

Notice how the music is written in

words followed by numbers. Unfortunately for modern researchers, this notation

system is completely unlike modern musical notation.

Firstly, staff notation would not be

invented for over two millennia; so right off the bat, we’re denied one of the

most useful reference points for figuring exact pitches. The same problem

exists in the 60-or-so surviving fragments of ancient Greek music; to resolve

this, and to allow relatively authentic reproductions of the music, a decision

was made by F. Bellermann in 1840 about which symbol would match which pitch,

based on replicas made of ancient Greek instruments. This has since been found

to be off from the actual tuning by around a minor 3rd (Pöhlmann,

Egert & West, Martin L. Documents of

Ancient Greek Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 2001. It’s a good book,

and contains all Ancient Greek music known to date). A similar general

consensus has been agreed upon for Mesopotamian music like the Hurrian Hymn. Of

course, in both the Ancient Greek and Mesopotamian cases, exact tuning varied

from location to location, since there was no international or even

interregional standard.

In addition to pitch, the tuning and

mode of a specific piece are just as important: the opening movement of

Beethoven’s 5th wouldn’t have quite the same vehemence if it was in

major (a.k.a the Ionian mode). On the Hymn tablet, the expression “ni-id

qib-li” in the last line refers to the mode. This matches the nid qabli mode

described in Babylonian musical documents. The fact that “ni-id qib-li” and “nid

qabli” don’t perfectly match isn’t an issue: in fact, all terms but one in the

notational half of the tablet are corruptions of musical terms used in the

native Akkadian language of the region of Babylon.

Here, however, a problem arises:

which modern mode matches “nid qabli”?

To answer that, you need to know a

little bit of background. You see, the Mesopotamian music system is based

around the harp or lyre (a portable harp, usually about the size of a laptop).

The 9 strings of the instrument were like modern harps in that each string was

one step up or down in the scale from the string beside it. The scales used by

the Mesopotamians had seven notes, just like modern Western music (A B C D E F

G). So, when there was a piece in what we nowadays would call a “major key”,

the harpist would have to tune his strings to, say, C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D.

Actually, it was a little more

complex than that. It wasn’t just the “key” of the piece that decided the mode.

Let’s say you had one of these ancient lyres. It would probably be painted with

bright colours, and if it was a court instrument (if you’re playing for a king,

you’re going to want to pomp it up and look as fancy and exciting as possible),

there would be gems and gold, silver and lapis lazuli inlaid in it. Now, let’s

say you wanted to play the melody from the beginning of Beethoven’s 5th:

(from Franz Liszt’s piano version)

You

see that’s in C minor. Now, if you tuned your strings to C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D,

you’ll run into trouble almost immediately: the string is tuned to E-natural,

but you have to play an E-flat! Now what do you do? Well, you have to re-tune

the instrument to the key of C minor. That’s exactly what the Mesopotamians

did, and each different tuning had its own name.

Now we get to the problem: which

modern mode matches “nid qabli”? That is, if you start playing in this tuning

on the first string and work your way up to the seventh string, what’s the

modern name of the mode that you hear?

In order to answer that, you need to

know if you’re going up or down the scale – that is, is string 2 lower or

higher in pitch than string 1? Not a single Mesopotamian document gives the

answer, so scholars have tried to find out indirectly, based on the phrasing

and ordering of tablets about tuning and music theory. So far, their opinions

differ. In general, most resources consider string 2 to be higher in pitch than

string 1, so by playing the strings 1-2-3- and so on, you’d get a rising scale.

However, several scholars, including Raoul Vitate, Martin West and Theo

Krispijn, raise an objection to this: based on images of people playing harps

and lyres from various Mesopotamian sites, as well as analyzing the meaning of

the names of certain strings, they concluded that the strings descended in

pitch with their number, i.e. string 2 would be lower in pitch than string 1.

So we know the name of the right tuning, but we don’t know what it means. Great.

It gets worse. Unlike what is done

today with melodies, where each note is assigned one specific pitch (e.g. A),

the system used by Hurrian Hymn 6 (and the fragments of other hymns found at

Ugarit) assigns each note a certain interval

(e.g. “embube”, matching Akkadian “embubu”, i.e. strings 3 & 7). If this

wasn’t confusing enough, a number occurs after each interval. This has caused

no end of confusion. Does this mean that both pitches are sung simultaneously

as many times as the number? (Remember the lyrics? This wasn’t just an

instrumental piece, it was a song!) Does it mean to sing a scale from one pitch

to the other, repeating certain pitches if the specified number is larger than

the number of pitches in the interval? Or does it mean something completely

different?

This is where practically all hope

of a definitive version breaks down. Aside from the fact that the majority

(Kilmer, Černý, West, Krispijn, Monzo) use the “two simultaneous pitches”

idea as the basis for their reconstructions, very little can be found in common

between the resulting pieces. Part of the reason why some researchers (Wulstan,

Duchesne-Guillemin, Vitale, Dumbrill) choose other interpretations is that

applying the “simultaneous pitches” approach means that one of the oldest

examples of written music is polyphonic, i.e. has more than one voice. Now,

it’s known that limited amounts of polyphony existed in ancient Greece, but even

there examples of it are rare and poorly understood (by modern readers). The

notion that the earliest recorded music may have been polyphonic seems almost

inconceivable: people usually tend to sing the same melody at the same pitch,

although men usually sing an octave below women. Polyphony is very complex: the

earliest definite examples of a

polyphonic tradition don’t appear until after the year 1000 A.D.! That’s over

2000 years after Hurrian Hymn no. 6 was written! If that isn’t reason enough,

only the vast minority of human musical traditions are polyphonic. Not

surprising, then, that researchers have been reluctant to accept its presence

in Mesopotamia.

END

OF MUSICAL TECHNOBABBLE. FEEL FREE TO BREATHE A SIGH OF RELIEF.

Now for the moment you’ve all been

waiting for: the realizations!

1971

David Wulstan

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Wulstan1971.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Wulstan1971.pdf

1974

A. D. Kilmer

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Kilmer1974.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/HurrianHymnNo6Kilmer1974.pdf

1977

M. Duchesne-Guillemin

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Duchesne-Guillemin1977.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Duchesne-Guillemin.pdf

(1977,

1978 Thiel NO MUSIC)

1982

Raoul Vitale

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Vitale1982.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Vitale1982.pdf

1988

Cerny

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Cerny1988.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/HurrianHymnNo6Cerny1988.pdf

1993

M. L. West

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6West1993.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6West1993.pdf

1998

R. J. Dumbrill

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Dumbrill1998.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Dumbrill1998.pdf

2000

Monzo

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Monzo2000.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Monzo2000.pdf

2000

Krispijn

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Krispijn2000.mid

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHymnNo6Krispijn2000.pdf

Each musical realization has

something in its favour, and since so little is certain about Mesopotamian

music theory, writing, performance – heck, Mesopotamian music in general –,

it’s more or less up to personal preference which version one finds most

convincing. In my case, I’m most familiar with the versions by Kilmer and West,

and have heard CD recordings of both. While Kilmer’s version has the strength

of a polyphonic realisation behind it, I prefer West’s version. Why? It sounds

so simple and austere, with a seriousness that suits the lyrics. After all,

this is a childless woman praying to a goddess to grant her offspring. That’s

hardly light subject matter! In addition, there’s an old rule called “Occam’s

Razor” that states “the simplest answer is usually the right one”.

For those interested, here are the

notes I made during my research. They include a very, very tentative setting of

the text to the version by West. Here’s a score version of it:

http://individual.utoronto.ca/seadogdriftwood/Hurrian/HurrianHumn6.doc