Visualizing

Variation

Alan Galey

Faculty of Information

University of Toronto

individual.utoronto.ca/

alangaley

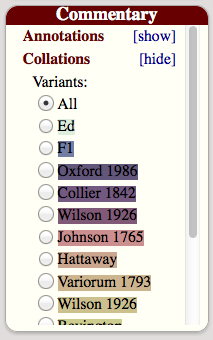

Animated variants

An important early claim made for digital scholarly editions was that they don't force editors and readers into choosing one variant over another. Instead of creating an implicit or explicit hierarchy of rejected variants subordinated to a single, supposedly authoritative reading, it was thought that digital editions could represent variants dynamically, presenting their ambiguity to readers not as a problem to solve, but as a field of interpretive possibility. Very few digital editions, however, have realized this possibility in their interfaces. One thing a digital visualization can do is make a virtue of ambiguity in ways that print cannot, combining the elements of time and motion to represent variants in ways that challenge the idea that texts are fixed and immutable.

This group of prototypes uses animation to cycle between different textual variants, presenting them as a field of possibilities to readers, and hopefully inviting readers to consider the evidence for and consequences of different possibilities. Animated variants also drive home the simple yet unsettling point that textual transmission is more often a matter of change than fixity: texts sometimes

The Animated Variants visualization was inspired partly by debates in Shakespearean editorial theory and partly by born-digital poetry, especially the early computer poems of bpNicol. Although the first prototype of this visualization was developed with Shakespearean examples in mind, my plan is to generalize them to handle as many different kinds of variation as possible. The single prototype posted here will likely become a group of visualizations that handle many different kinds of textual variation, including variants in words, phrases, lineation, stage directions, and manuscript revisions. For now I have posted a simple first version that cycles between variant words and phrase, as shown in the box above.

Background

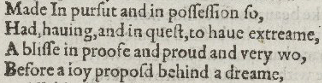

The visual display of textual variants has a long history, one closely linked to changing traditions of scholarly commentary on ancient texts. Although Shakespeare was a modern writer, the complexity of his texts (in terms both of multiple authorities and of editorial emendations) provoked various attempts to represent textual variation systematically. The two examples below show a famous textual crux from Hamlet in which the Folio’s Hamlet wishes that his "solid flesh" would melt, while the Hamlet of the first two quartos (Q1: 1603 and Q2: 1604/5) says "sallied flesh" (which some editors, following Theobald, have emended to "sullied flesh"). The difference between "solid flesh" and "sullied flesh" is consequential: if Hamlet refers to himself as "sullied" at this point in the play, he appears to be accepting the taint of his mother's incestuous relationship with his uncle, who killed his father and usurped the throne of Denmark; yet if Hamlet simply refers to his flesh as "solid," the metaphor remains physical rather than moral, without the same hint of guilt.

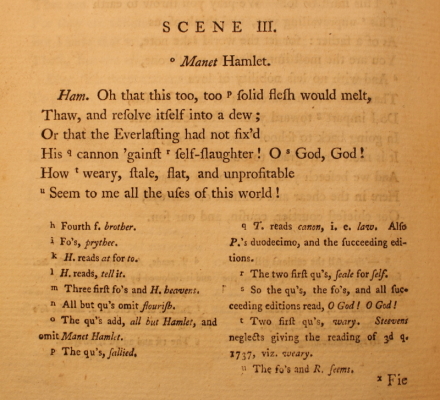

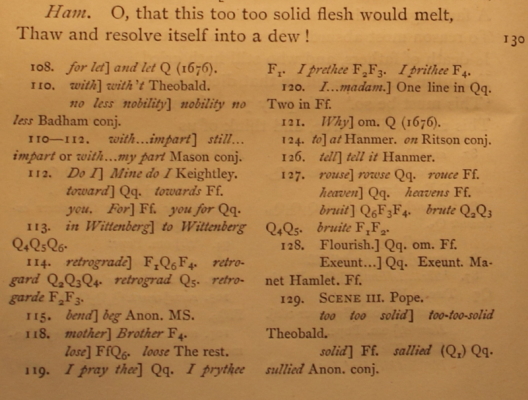

Pictured below are two examples of how print editions represent this moment of textual ambiguity. The image on the left shows textual notes from the earliest attempt to provide a complete collation of textual variants on the same page as the Shakespeare text. Its editor, Charles Jennens, felt that readers should be presented with textual evidence in a way that was clear and engaged their critical faculties: his notes were invitations to readers to think about the nature of the text. The image on the right comes from about a century later, showing how the same apparatus had grown in size and complexity in the first Cambridge Shakespeare editions. The Cambridge textual notes became the standard syntax (with some refinements) for critical and variorum editions down to the present.

|

|

| Charles Jennens, ed., [Five Plays of Shakespeare], vol. 1 (London, 1770-1774). Photo by Alan Galey, courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library. | William George Clark & William Aldis Wright, eds., The Works of William Shakespeare, vol. 8 (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1863-1866). Photo by Alan Galey, courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library. |

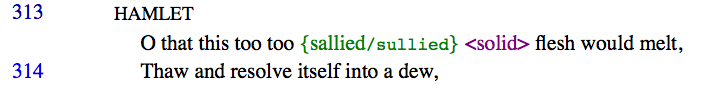

The syntax for textual notes can be off-putting, even to specialists, with some calling them a band of terror running under the text, or barbed wire fencing it off from readers. Some digital editions of Shakespeare have attempted to solve this problem using combinations of colour, inline visual flags, and reader-selected levels of annotation. For example, the "solid/sallied/sullied" crux in Bernice Kliman's Enfolded Hamlet project, uses a combination of these elements, along with different typefaces, to show significant variants and emendations within the line itself, with the result that textual variants no longer lurk decontextualized at the bottom of the page.

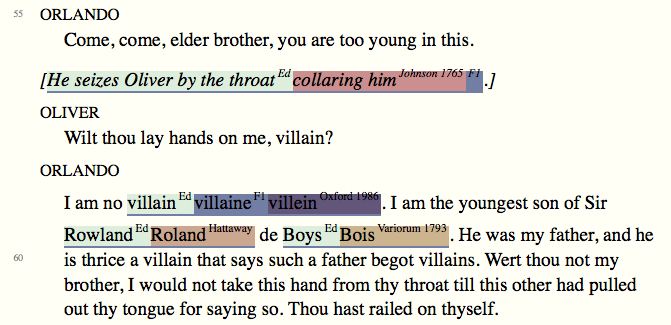

The Internet Shakespeare Editions takes a similar approach in its modern editions, such as David Bevington's As You Like It, shown here. Again, the elements of colour, inline positioning, typographic flags, and in this case a lookup table at the top of the page serve to indicate variants without resorting to abstract notes.

|

|

Prototype

One element that the digital editions mentioned above don't use is time. I built the first prototype offered here after conversations with Michael Best and others about the potential for animation as a visual technique. About ten years ago I created a simple animated gif for Michael showing how stage directions could be animated to act out the hidden ambiguities of dramatic texts. Several years later, I created the v.1 prototype offered here to see if animation could be applied to actual text in a web browser, not just an image containing text. I plan to post 2 or 3 versions of the animated variants prototype in total, but for now am posting only v.1.

Version 1: simple animation

Sample 1: animatedVariants_v01_HamletMacbeth.xml

This is the version you can see working in the Hamlet example at the top of the page and repeated here. This version uses the animation script in its simplest form, and works best with single words and phrases. It could be especially useful for words that are often emended, but whose original spelling permits the kind of ambiguity that we sometimes find in early modern orthography.

For example, when Banquo uses the word "weyard" in Macbeth to describe the witches in the 1623 Folio text, he could mean "weird" in the sense that the witches are agents of fate, or he could mean they are "wayward" in the sense of aberrations from the natural order. In print, editors have tended to choose one emendation or another, sacrificing ambiguity, or have retained "weyard," which likely still requires a gloss for modern readers. However, an animated digital word like "

The variant should be encoded using the Text Encoding Initiative's <app> element, as defined here. For example, the XML for the Hamlet example looks like this:

Some of the information here isn't strictly necessary, like the

who="Hamlet" or wit= attribute/value pairs, but the relationship of the <app> element to its children and siblings gives a sense of how (more or less) TEI-compliant code handles simple variation.

This sample file shows a couple of XML variants in a standalone file, with some CSS and Javascript to handle the animation. Two user-defined parameters, the letterChangeRate and variantChangeInterval, are defined at the top of the Javascript section in milliseconds. The getReadings() function gathers the original readings and variants into readingArray objects, and then the cycleVariants() function sets the animation going perpetually using windows timeouts. In this example, the animation is set in motion when getReadings() is triggered by the document body's onload event handler, but getReadings() could just as easily be triggered by user interaction with some minor modification. Animation could also be turned off by clearing the timeouts saved in the global intervals array.

Version 2: CSS3 transition effects

Sample 2: animatedVariants_v02_HamletMacbeth.xml

The revised prototype you can see working here, and implemented in animatedVariants_v02.js, reflects how valuable it is to receive just the right feedback in just the right context. When I demoed the animation above at the Folger Shakespeare Library's Early Modern Digital Agendas summer institute, an audience member suggested that the animation prototype (version 1) could prompt some readers to infer that all variants are authorial. As this person astutely pointed out, to a reader whose eyes are used to the visual conventions of live chat boxes and real-time collaboration in Google Docs, the letter-by-letter animation might connote a live typist, as though some invisible author was typing, deleting, and rewriting digital text before our eyes. Literal misinterpretations by readers along these lines seems unlikely, but as with so much else in visualization, the connotations and rhetorical effects of design shouldn't be ignored. I had not considered this interpretation of the animation prototype's visual codes, given that my approach to textual theory tends to place the author as one among many agents that shape a text in transmission, but this bit of feedback proves the value of seeing one's own designs through the eyes of others.

It's likely that this new fade effect carries value-laden connotations of its own. One might object that the red fading slowly to black might suggest the heat of composition cooling into the permanence of inscription, even though the sequence of variants here doesn't necessarily reflect the historical order of change. For example, in this Hamlet variant, the sequence of changes tended to run from "sallied" (printed in Q1) to "sullied" (an editorial emendation of "sallied"), not the other way around.

For these and other reasons, I've made this prototype considerably more modular and extensible. From this version forward, I'll put all the Javascript in a standalone file; for this version, it's animatedVariants_v02.js. This version also allows one to set different animation styles on a case-by-case basis, by adding a local animation attribute to any containing element that also carries a unique id value, such as <sp> or <text> or even a generic <div>. Possible values for animation consist of fade and typing, though that will expand in future versions. For example:

Sample 3: animatedVariants_v02_sonnet129.xml

Note that in v02 id and animation attributes are now required to trigger animations, and all <app> elements require their own unique id as well. One of the advantages of localizing the animation style to the XML, rather than setting it as a single global variable in the Javascript, is that one can now have different animation styles running at the same time. You can see that at work on this page in the sample file linked above. In that sample file, I've kept the Hamlet and Macbeth cruxes for reference, with their animation values set to fade, and below them added an example from Shakespeare's Sonnet 129 ("Th' expense of spirit in a waste of shame"). This example also shows us a different kind of variation: it doesn't cycle between variant readings from source texts such as F and Q2 Hamlet, but between the 1609 quarto text of the Sonnets and its modernized form.

In the sample file I've also used a <table> element structure (a clunky and late-1990's approach, I know) to arrange the digital transcription alongside an image of the 1609 printing (courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library's Luna collection). In the code you'll notice that the id and animation attributes can even be attached to the <table> element, not just to the immediate containing element for the animated text.

Another advantage of this revision is that the code governing the fade effect, which I've added to the cycleVariants() function right below the lines for the typing animation, makes use of CSS transition effects. These add considerable functionality to the CSS3 spec, and enable a range of animation and other motion- and time-based effects. As I've noted in the comments in animatedVariants_v02.js, the new CSS transition-based code will allow me and anyone else revising these prototypes to explore a greater range of visual possibilities than version 1 did. If you want to explore CSS transitions, I recommend getting to know MozDev's helpful list of animatable CSS properties.

In future versions, I plan to add visual cues to alert readers to the source of the variants currently visible. I'll also add a mechanism to prevent different variants from different sources from appearing at the same time, giving a potentially false impression of words appearing together in the same source. I'm also considering how to handle more complex forms of variation like relineation and stage directions, perhaps using CSS3 animations.