Masculine Danseur?

Even

before the French Revolution, there were concerns about the “manliness” of

the ballet profession and these anxieties became more pronounced as the

nineteenth century progressed. This often cited quote by Jules Janin (Garafola

1985),

written in 1840, provides a clear idea of what was considered manly and

what was

not (and the male dancer was definitely not):

Even

before the French Revolution, there were concerns about the “manliness” of

the ballet profession and these anxieties became more pronounced as the

nineteenth century progressed. This often cited quote by Jules Janin (Garafola

1985),

written in 1840, provides a clear idea of what was considered manly and

what was

not (and the male dancer was definitely not):

“…

a man, a frightful man, as ugly as you and I, a wretched fellow who

leaps about without knowing why, a creature specially made to carry a musket

and a sword and to wear a uniform. That this fellow should dance as a woman

does – impossible! That this bewhiskered individual who is a pillar

of the community, an elector, a municipal councilor, a man whose business

is to make and unmake laws, should come with a hat with a waving plume

amorously caressing his cheek, a frightful danseuse of the male sex, come

to pirouette in the best place while the pretty ballet girls stand respectfully

at a distance – this is surely impossible and intolerable." (p.

37-38)

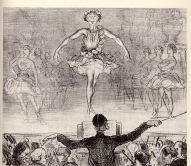

A lithograph by Honoré Daumier captures these

sentiments in visual form, the “abnormality” of the danseur

evoked by this figure’s awkward stance and scrawny physique. The

ballet clearly was not the natural environment of a self-respecting “man.” The

pomp and ceremony with which masculinity had displayed itself during the

previous century was supplanted

by the image of the modest, frugal and industriousself-made

man in the nineteenth century

(Kuchta 1996).