| Methodology |

|

Annotated Bibliography |

|

Second Term Plan |

Methodology

The study of three brush and comb sets have brought up questions of class differentiation and emulation, gift giving as life transition ritual, gift giving as a symbol of bonds between women, and hair brushing as a symbol of womanhood, sexuality, and class.This study has reviewed a celluloid comb and silver plated comb holder, a celluloid brush set, and a silver brush set. The celluloid items are from a middle class background, and the silver items are from an upper middle class background. The exploration of the celluloid brush set has focused on the brush and comb of the set and ignored the mirror. The exploration of the silver brush set has focused on the lady's hairbrush and the clothing brush while ignoring the mirror, and comb. These varying focuses were taken in order to explore different meanings and aspects of combs, hairbrushes, and clothing brushes.

|

| Ivory brush set from Japan bought by Harris family in 1892. |

Use the links below to jump to parts of this document:

- Methodology, how it was derived

- Methodology, the final product

- Methodology applied, the celluloid comb and comb case

- Methodology applied, celluloid brush and comb

- Methodology applied, silver ladies brush and clothing brush

Methodology, how it was derived

There are various methodologies incorporated into the following version. No single model is sufficient for this study because authors of methodological articles have had a variety of objects in mind when they wrote their articles; none of the authors created a methodology specifically for hairbrush sets. The methodological articles read focused on landscape, cemeteries, churches, T-shirts, the poker, coke bottles, clothing, textiles, furniture, and pottery. Using these various articles, the researcher has chosen elements of each methodology that are relevant to the study of hairbrushes, combs and clothing brushes. Specific authors are mentioned within the developed methodology. Please see the complete methodology bibliography for full citations.

Here the major influences of the methodological categories will be highlighted. One of the major influences on this methodology was G. Finley's "level one" from the article "The Gothic Revival and the Victorian Church in New Brunswick". As can be seen below the hair brush methodology has incorporated the five properties of artifacts: material, construction, function, provenance, and significance. Level two of Finley's methodology which defines larger research questions and allows for creative scholarship has been replaced by the annotated bibliography section of this website as well as J. Prown's final category from his article "Mind in Matter": speculation. Speculation is a particularly important category because it allows for researchers to let their imagination take over after the mind has been confined by the narrow categories that have preceded. As can be seen, the rest of Prown's methodology has been scattered throughout Finley's five categories thus helping to expand on Finley's definitions. Another author that is integral to the brush methodology is J. C. Dupont. Dupont has provided the categories of verbal expression and symbolism, allowing researchers to look at fairytales, myths, and iconography, in order to find special properties of the brush sets. Symbolism and verbal expression are equivalent to Finley's second level. As with Prown, Dupont's ideas have been used to elaborate the categories provided by Finley.

A. Forty has been useful in his discussion of innovative objects. He asserts that the design of new objects plays tricks on our sense of history. In order to be accepted, an innovative object must hide itself in a utopian, archaic, or futuristic design. Forty was the inspiration in category number eight: design.

J. Market has been incorporated into the brush methodology through supra categories: object as instrument and object as sign. These categories are used as a guideline. Researchers know that they must refrain from making interpretations in categories one through five. Interpretation commences in the final section: object as sign.

Various other methodological writers have been incorporated into the ten main categories as minor theorists. These are B. Cullam-Swan, J. Fleming, J. Hunt, and A. Martin. There are also various models that have not been incorporated into the brush methodology. These are methodologies that cannot be used for a small object such as articles that focus on landscape such as F. Lewis, I. Brown, and D. W. Meinig. Also excluded are methodologies that are similar to those already employed such as G. McCracken who studies the meaning of objects to their makers, owners, and observers, and the transfer points such as advertisement and gift which are incorporated into Finley's primary function category.

Methodology, the final product

Object as instrument: non-arbitrary practical use (Marquet 30)

1) Material: The composition and appearance (Finley 8). Begin with the largest most comprehensive part of the description then move to particular details (Prown 1982, 7). Look for colour, light, and texture. How are these distributed? (Prown 1982, 8)

|

| Painting of 'The Lady of Shalott' (Gitter 940) An example of the connection between hair and weaving. The bar at the woman's feet displays spun thread, the thread has come alive encircling the lady as she tries to escape. |

3) Primary Function: Why was the object created and how it is used? (Finley 8) Consideration should be given to the physical adjustments a user would have to make to its size, weight, configuration, and texture (Prown 1982, 9). How does shape alter the function? (Dupont 2) Give consideration to the shape knowing the different functions the item might have i.e., what hairstyles were made with this brush? (Dupont 4) Were there class differences in brushes? (Dupont 7)

4) Unintended functions: What are the secondary functions of object? (Finley 9) The way things are used can depend on the economic condition of the user (Dupont 2).

Object as sign: arbitrarily decided (Marquet 30)

5) Provenance: The chronological story of the brush. Where and when was it created, by whom, and who was the owner? (Finley 8) Where is the researcher viewing the object and how does this affect understanding? (Dupont 4)

6) Significance: The meaning in earlier contexts to its maker, owner, and users (Finley 8). The maker and user may be influenced by the fashion system which produces images to market and sell as alternatives in appearance (Cullam-Swan 417). What social roles or status does this object suggest? (Cullam-Swan 418)

7) Design: Products aim to create acceptance to innovation by using design to represent them as something other than they are (Forty 11): futurism, utopianism, archaic model, or incorporation into something else (Forty 12).

8) Verbal Expression: Are there fairytales or myths that incorporate the brush? (Dupont 14) What words are used to explain the construction of the brush? (Fleming 43)

9) Symbolism: In symbolic thought the object is never only itself but a receptacle of something else. Look at fairytales and folklore to find stories involving magical brushes and the meaning of hair (Dupont 10-11)

10) Speculation: The mind of the observer is allowed to make free associations (Prown 1982, 10). Think of broader context of society, what this object tells us about i.e. consumption, domestic life, socialization, establishment of a concept of self (Dupont 18). Did this object alter architecture? Buildings change depending on new goods, and changing social behaviour i.e. were these used in a bedroom, in a bathroom, or in some other room? (Martin 146).

|

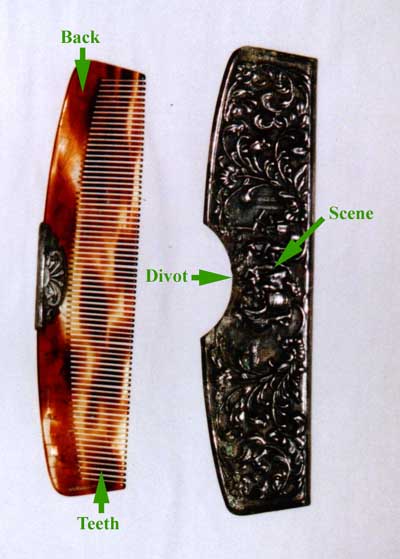

| Celluloid comb and case defined. |

1) Material: This is a simple single comb made of celluloid. The comb is blotched with brown, auburn, yellow, and clear colouring. The back of the comb is auburn and clear, and the teeth of the comb are yellow and brown. The back of the comb is cracked but not broken. The cracks can be felt when passing one's fingers over the back of the comb. In the middle of the back there is a semicircle silver-plated copper adornment with leaf-like design that extends towards the comb. The design is raised, rather than inlayed, in the copper. The metal has broken and is no longer attached to the comb. There are designs in the plastic which indicate that the metal is meant to be attached to the comb. The copper semicircle matches the brush case that is also made of silver-plated copper and includes a raised design. The design on the case is leaf-like with flowers towards the periphery and a raised border around the edge of the case. The border extends all the way around the case except in the divot where the semicircle of the comb appears when the comb is placed in its case. The leaf design is identical on both sides of the scene that resides in the middle of the case. The scene is of four people and a dog. The middle of the case will be described from left to right. On the far left there is a man with his right arm leaning on a barrel, he may be engaged with items that lay on the barrel that are indecipherable. The man faces a woman who is sitting behind him and behind the barrel. The woman's left arm is extended upward to meet the shoulder of another man. Her right arm extends across her body as she holds an indiscernible item upon her lap. At the woman's feet, but in front of the barrel, is a dog. There is a third man standing behind the woman who plays a violin and faces the audience. The head of this man reaches to the top of the divot where the brush's silver-plated semicircle meets the case. Beside the violin playing man there is a sitting man who has one foot extended with one arm crossing his body and another hand sitting on his knee. This man faces into the circle, towards the first man. Both this last man and the first man are wearing hats while the middle two are bare headed. At the foot of the man to the far right is a pot about one sixth the size of the barrel. To the right and back of this man is a well on a square wood stand with a structure that extends like a pyramid above it and a pump that extends to the right of the well. There are trees surrounding the scene in the background. All of the ornamentation described here is repeated on the other side of the comb holder.

2) Construction: The comb is 11.5 cm along the length of the teeth and 13 cm along the back. The teeth are 1 mm in length and have a space of 1 mm on either side of each tooth. The comb is 1.5 mm in depth. It is 2.5 cm in width at its largest point and 2 cm in width at its smallest point. The teeth are even at the bottom, but they extend into a curve as they move upward into the back of the comb. The back of the comb is curved; the middle of the back where the copper semicircle attaches is the fullest extension of the comb. The dimensions of the case are the same as the brush if one adds 1.5 mm to each dimension given above. The quality of craftsmanship is not high. One can tell this because the semicircle has broken off the top of the comb, the celluloid is cracked, and the silver-plating has begun to give way to the copper, leaving a green tint on certain parts of the comb and the case. The case and comb were most likely done with a mold, which is indicated by the exact replication of the designs on the front and back of the case and the perfect symmetry of the comb. Since a mold was used in both the construction of the case and comb, this insinuates that they were mass-produced. There were few stages of assembly for both the comb and the case; there are no joints or rivets on the comb which would indicate that there were various stages of assembly. In creation, the case was folded in two, cut into the shape of a comb, and imprinted with a design. The semicircle on the comb and the comb case have a natural, or a Rocco, style with a flower and leaf motif. The top right and left corner of the case has flowers that are reminiscent of forget-me-nots. Also, the scene in the centre of the case is reminiscent of folk culture. There is an inscription on the bottom of the case along the width that says, "made in Denmark". There are no indications of company, artist, or markings stating the calibre of silver used. These factors indicate that the craftsmanship was not high and that the item may have, once again, been mass-produced.

3) Primary Function: A comb is used to take the knots out of long hair, to straighten short hair, and to coax strayed hair back into a hairstyle. This comb in particular was carried with its owner out of the house to dances, on shopping trips, and for visits to other people's homes. This function is indicated by the case that helps to protect the teeth of the brush when in transport, and by the beaded dress-purse in which the comb was found, accompanied by a dance card. The light weight of the comb and its case are further indications that it would be carried as a travel comb. The comb is slightly larger then a lady's hand, and the back is just large enough so that the thumb and fingers do not extend onto the teeth which would impede the function of combing. The yellow and brown colouring of the teeth indicates that the brush was in use in the past. The differing colour of the back and the teeth is due to the oils of the hair which have yellowed the celluloid.

4) Unintended functions: Since this is a travel comb, could have been used as an indication of the identity of the user to her audience. The design of the comb and its case may have been chosen as an indication that the user valued nature and folk life. The silver finish could have been used to indicate personal affluence. However, the fact that the comb is not solid silver is indicative of the class of the owner, and her pretence to appear wealthier then she may have been.

5) Provenance: As stated earlier, the comb was made in Denmark for export to England, America, or Canada. This assumption can be made because the label is in English rather than in Danish. The comb was bought and owned by Mini Present who was born in 1880. Present's family owned a general store from 1840 to 1880 in Guelph, Ontario. The comb could have been purchased in Guelph or when she moved to Detroit with her married sister between 1895 and 1900. This would place the comb in the decade before the turn of the century. The comb was passed down as an heirloom to Patricia Skidmore in 1960 when her great aunt Mini died. The comb was given to Skidmore as a reminder of her aunt. It now sits in a washroom in Skidmore's condominium as ornamentation. The comb is not presently in use to brush one's hair. The researcher has viewed the comb in Skidmore's home, where it currently resides.

6) Significance: One can assume that the makers of the comb were aware that the comb was made for export, which assumes that the makers knew of their involvement in a global system of trade. The meaning of the object could, therefore, indicate a sense of connection with the world that extends past the regional context. The design of the comb may incorporate assumptions about what English speaking countries knew about Denmark. The designer(s) may have stereotyped themselves as pastoral, community based, music loving, and in tune with nature in order to market the comb as an authentic artifact from Denmark. To Present, the owner and user of the comb, it may have been used as an outward indication of travel, or connection with other cultures. As such, the comb would have been an indication of affluence. Alternatively, it could have been fashionable to own combs with such motifs at the time, or the comb motif could indicate a divergent choice to the fashion system when the comb was bought. More research on the motifs of comb cases must be done in order to determine where this comb fits into the fashion system. Present valued the comb for its adornment and kept it intact long enough to pass it to her grand niece.

7) Design: The colouring of the comb itself indicates that the makers were following an archaic model. This product aimed to create acceptance to the innovation of celluloid by disguising it as tortoise shell. The combs and hairpins of affluent Victorians and Edwardians were often made of tortoise shell. The lower middle class to which Present belonged, attempted to emulate the upper class by purchasing items that were disguised as tortoise shell, and plated with silver.

8) Verbal Expression: The words used to describe the comb are also used to describe elements of a person. For example, back and teeth are both descriptors of combs and of humans. Household items that are intimately used with the body tend to acquire the wording of the body. Also, by using natural, or humanistic, words to describe the comb, the social aspect of sculpting one's hair becomes hidden. This observation could also explain the natural motif of the comb case which could be indicative of a subconscious rejection of beauty culture. By hiding the comb in a case that depicts nature, the social aspect of brushing one's hair also becomes hidden. Furthermore, brushing one's hair in public was considered a sexual act by Victorians. Perhaps the comb cover was used as a way to hide the fact that women had to comb their hair in public washrooms to maintain their appearance as ladies.

9) Symbolism: Hair was to be brushed one hundred times before a Victorian woman went to bed. This was said to even out the oils of the hair making it shine. Hair brushing was part of a beauty ritual that confirmed high birth. Victorians had various fairytales that confirmed the connection between hair and class. For example, The Goose Girl is the story of a princess that traveled to marry a prince from another kingdom that she had not yet met. On the journey, her maid took her place and forced the princess to become a goose girl while the maid married the prince. Later, the king saw the goose girl's beautiful shiny blond hair and realized that she was royalty (Gitter 939).

The brushing of one's hair in public was considered to be an indication of sexual availability (Gitter 938). Lack of tidiness of hair also indicated one's sexual availability. Victorian novels frequently describe women's hair when explaining her character; the governess and the loyal wife had well groomed hair, while the unfaithful, passionate woman had ill-kept, messy hair (Miller 91). The colour of a woman's hair was also indicative of her sexuality; the blond was cool and pure, while the dark haired woman was passionate and erotic (Miller 91). There was also a strong connection between hair combing and the spinning of thread (Gitter 939). These were both considered to be woman's work. The hair and the thread sometimes combined to create a textile that helped to confirm family solidarity, but at other times hair and thread combined to create a web that brought the family's downfall.

In the above examples, a woman's hair is a receptacle for her hidden identity. Affluent Victorians kept a hair safe on their vanity where they placed the hair that came out in brushing and combing. This hair could then be used for jewellery, to create collages that went in frames, or as ornamentation in snuff boxes, and other display cases. Hair and the practice of hair brushing was a very important element of the everyday life of Victorian women. Hair combing took on meanings of identity, of memory, and of decor beyond the everyday.

10) Speculation: Why would one have a representation of nature and folk culture combined with beauty culture? Was this a denial of beauty culture? Was there a romanticism of Denmark at the time? Did the image on the case come from a popular painting? What do other items of ornamental export from Denmark look like?

|

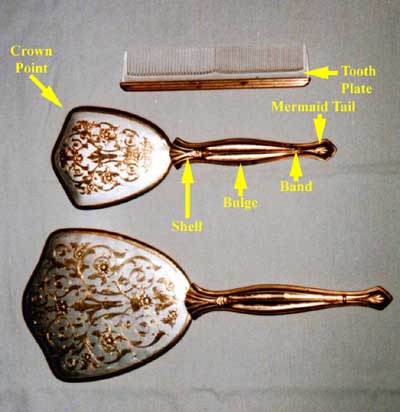

| Celluloid brush, comb, and mirror defined. |

1) Material: This is a simple singe comb made of celluloid and tin. The comb teeth are made of celluloid and the back is made of tin and is painted in gold. The teeth are clear, and the back is gold coloured. The back has rounded edges but is otherwise straight. There are three raised ridges that extend in a parallel fashion along the back. The teeth extend into a tooth plate before it is joined with the back. The tooth plate extends parallel to the teeth and the back but points slightly towards the teeth in the centre.

This is a woman's brush and has a slender neck of tin, a back that displays a motif that is covered with clear celluloid, and framed with tin. The faceplate and bristles are celluloid. The celluloid on the brush is clear and the tin is painted in a gold colour. The tip of the brush handle points downward in a shape similar to a mermaid's tail. The handle gets thinner, and then draws outward into a slight bulge towards the top-middle. The handle then flowers outward, in a seashell shape to incorporate the brush. The bottom of the brush towards the handle is oval shaped, but the midsection of the brush extends outward and creates three crow points at the top. Below the shell shape on the top of the handle is a flower with a band underneath, and above the mermaid tail is another band. The handle is identical on both sides of the brush. It also has a distinct texture because it has four ridges that extend like a pyramid into the middle of the handle. The back of the brush displays a gold design of leaves and flowers, not dissimilar to the comb case design. The right and the left side of the design are identical. The flowers are surrounded by vines and leaves, which incorporate the flowers in a circular pattern. The gold design is surrounded by a silver coloured backing. The material used for the design on the back cannot be discerned because it is covered in clear celluloid.

2) Construction: The comb is 17 cm in length, 4 cm in width, and 2.5 mm in depth. Half of the teeth are 1 mm wide with 1 mm of space on either side, while the other half is 1 mm wide with 2 mm on either side. The tooth plate is 0.5 cm in width and extends the length of the comb. The back is 1.7 cm in width and extends the length of the comb. The comb's teeth and back were mass-produced using a mold. One can discern that the comb was mass-produced because the tooth plate has a perfect circular indent that indicates the place in which the molding machine left its mark. Also, the plastic on one of the edges of the celluloid ledge is partly unfinished indicating that the machine did not make a clean cut when molding the celluloid. The comb was made in four stages: molding the celluloid, molding the tin back, painting the tin back, and attaching the back to the comb. This particular design is geometrical, representing rationality due to the three raised ridges in the back of the comb. This conclusion can only be drawn when looking at the comb in isolation because, as will be discussed presently, the constellation of objects with which the comb is associated use a natural motif. There is no inscription of company, artist, or designer, but the comb does have a "made in USA" label in the tooth plate.

The brush is 26 cm in full length. The neck is 14.5 cm long and 2 mm wide at the base of the tail, 2 cm wide at the extended part of the tail, 1cm wide at the first band, 2.5 cm wide at mid bulge, 1.2 cm wide at the second band, and 3 cm wide at the extended part of the shell. The brush face is 2cm wide at the base of the oval, 8.5 cm wide at midpoint, 9cm wide between the two crown points and 1 cm wide at the upper most crown point. The bristles of this brush contain 12 bristles per bunch, the bristles in each bunch vary in length by up to 3 mm, the longest bristles are 1.5 cm in length and there is 0.5 cm of space on either side of each bristle bunch. When one looks straight down at the bristles of the hairbrush the brush does not look full, and the bristles of each bunch do not touch one another. The celluloid bristles are not very flexible, but they cannot penetrate fully into a woman's thick hair. The brush seems to be mass-produced; one can tell this by the gold motif on the back that seems to have been stamped on. The gold flows outside the lines provided, and sometimes does not fill every leaf and flower. There were eight stages in manufacture for this brush: make bristles, mold bristle plate, mold frame, mold metal that extends from frame into the handle, mold back, print back with gold, mold handle, assemble the brush. There is no indication of the company, maker, or artist of the brush design and there is no indication of the country of origin.

3) Primary Function: A comb is used to take the knots out of long hair, to straighten short hair, and to coax strayed hair back into a hairstyle. The brush, on the other hand, was created in order to disperse the oils of the hair evenly from end to end. One can tell this because the celluloid bristles do not penetrate the hair completely; this is partly because of the short length of the bristles. The bristles were probably made to be short because celluloid is much stiffer than the preferred brush bristle or boor's hair; in order to emulate the lack of penetration into the hair afforded by boor's bristles, the celluloid bristles were shortened. In this way, the celluloid brush attains the same function as does the boor's hairbrush, the moving the oils from one end of the hair to the other. Victorian ladies brushed their hair one hundred times to make it smooth and shiny before they went to bed. A lady was to use the brush primarily on the hair that grows from the top of the head, rather than the underside hair which grows from the bottom of the skull and the neck. Due to the large size of the head of the brush, it is difficult to manipulate the brush so that it can reach this under-hair. The ridges on the brush's handle allow for a firm grip when brushing one's hair.

4) Unintended functions: A secondary function of this brush set was class emulation. When using this brush, the owner, a working middle class woman, emulated the hairstyling techniques of women who could afford brushes made of more expensive materials. By doing so, she was able to blur the boundaries between the middle and upper classes. This idea will be further discussed in the section on provenance. The brush's design and function as ornamentation, was emulative of more expensive style brushes. The brush also served an unintended function of family heirloom which has helped to form a bond between women of the same bloodline but who have different last names due to marriage.

5) Provenance: This brush set was created in USA. The identity of the manufacturer and the designer remains unclear. The set was first owned by Alma Peru, who was born in 1880 on a farm in Michigan. The set was most likely bought for Peru as a young woman before her marriage into the Owaso family at which time she moved to Detroit in 1910. This would date the set before the turn of the nineteenth century. The Owasos lived in a two-storey brick house; they employed a maid-of-all-work who did not live with them. This would make the family middle class. During the depression, when the house and the family business where lost, Mrs. Owaso took a job as a detective on the city bus system to observe whether or not the drivers stole money. During this period it was necessary for Mrs. Owaso to dress as an upper class lady who was on her way to up-scale shops in downtown Detroit. As a result, she frequented a salon twice a week to maintain the proper hairstyle. This is an excellent example of a middle class working woman emulating an upper class woman in appearance and hairstyle. On the days that Mrs. Owaso did not visit the salon, she would have had to maintain her hairstyles with the brush and comb under observation. Four children where born to the Owaso marriage, the only girl was Gail. Gail married into the Farmer family in 1939 at which point the brush set was given to her as a wedding gift. In 1980 Mrs. Farmer died giving the set to her granddaughter Kate Skidmore in her will. Kate's mother, Patricia Skidmore, is currently in possession of the brush set until Kate resides in a permanent residence. The set was observed by the researcher at the home of Patricia Skidmore.

6) Significance: The meaning of the brush to the first owner was as a symbol of graduation from girlhood into womanhood. There was a popular Victorian saying about this passage from one stage to the other: women 'let their skirts down, and wore their hair up' as they grew out of girlhood. In order to wear one's hair 'up' a brush and comb must were given to facilitate the new hairstyle. The meaning of the set changed with the second owner because of the time at which it was given. The brush set was a wedding gift and could be considered as a sign that the mother approved of the union. The set continued to act as a transition marker for a moment of life change. The meaning of the set changed a third time in its final ownership. At this point, the set can be considered a family heirloom; it was given upon death to the granddaughter, who will in turn give it to her daughter, or granddaughter upon death. The brush set continues to be a transition marker because Kate Skidmore will not receive the set until she has acquired a permanent residence. The moment of the transition of the brush set speaks to the changing importance of moments in a woman's life. In the Victorian period, a period in which childhood was becoming an important concept, the transition into adulthood was a significant social event. In the post-war period, marriage was considered to be an important event because men had been away in the war and unavailable for marriage earlier in the decade. Finally, in the current age, a woman's education and subsequent career are generally considered the most important events in a woman's life.

The brush set was used by the first two owners but was also a form of ornamentation. The third and fourth possessors do not use the set, they keep it only as ornamentation. This is partly a sign of the changing needs for women's hairstyles. The current owner is not involved in a beauty culture. She has short hair and does not see a need to disperse the oils in her hair, or to brush her hair one hundred times to make it shiny. These practices were much more relevant to women with long hair who were part of a beauty culture.

7) Design: The brush set aims to create acceptance for its innovation as a celluloid product through the use of colour. The set uses gold and silver colouring which emulates the traditional metals used for brush sets. Furthermore, the shape of the handle and the head and crown are equivalent to the more traditional set reviewed below, this emulation of traditional design can be viewed as a technique to create acceptance to the innovation of celluloid.

8) Verbal Expression: As noted in the material section, the brush handle appears to have a mermaid tail, and the section of the handle that meets the brush head is in the shape of a shell. These allusions to the sea and mermaids in particular should not go unnoticed. Victorians told fairytales about mermaids who seduced sea-fairing men by brushing their hair while sitting on rocks. Brushing one's hair in public was considered by Victorians to be sexually enticing. Since hair brushing was considered to be an affair for the private domestic sphere, it is interesting to note the natural, and therefore public, motif on the brush. Here the brush set can be seen as an artifact that transcends the public/ private sphere dichotomy. Furthermore, the incorporation of the mermaid tail into the brush motif points to another Victorian dichotomy: the angel and the whore. The mermaid was seen as sexual, while the domestic well-groomed woman was seen as pure. Once again, the brush negates this Victorian distinction between angel and whore by incorporating the iconography of sexuality in its design, yet the private use of the hairbrush itself symbolizes purity.

9) Symbolism: This section is repeated from the above methodology. Hair was to be brushed one hundred times before a Victorian woman went to bed. This was said to even out the oils of the hair making it shine. Hair brushing was part of a beauty ritual that confirmed high birth. Victorians had various fairytales that confirm the connection between hair and class. For example, The Goose Girl was the story of a princess that traveled to marry a prince from another kingdom that she had not yet met. On the journey, her maid took her place and forced the princess to become a goose girl while the maid married the prince. Later, the king saw the goose girl's beautiful shiny blond hair and realized that she was royalty (Gitter 939). The brushing of one's hair in public was considered to be an indication of sexual availability (Gitter 938). Tidiness of hair also indicated one's sexual availability. Victorian novels frequently describe women's hair when explaining her character, the governess and the loyal wife had well groomed hair, while the unfaithful, passionate woman had ill-kept, messy hair (Miller 91). The colour of a woman's hair was also indicative of her sexuality; the blond was cool and pure, while the dark haired woman was passionate and erotic (Miller 91). There was also a strong connection between hair combing and the spinning of thread (Gitter 939). These were both considered to be woman's work. The hair and the thread sometimes combined to create a textile that helped to confirm family solidarity, but at other times hair and thread combined to create a web that brought the family's downfall.

In the above examples, the woman's hair is a receptacle for her hidden identity. Affluent Victorians kept a hair safe on their vanity where they placed the hair that came out in brushing and combing. This hair could then be used for jewellery, to create collages that went in frames, or as ornamentation in snuff boxes, and other display cases. Hair and the practice of hair brushing was a very important element of the everyday life of Victorian women. Hair combing took on meanings of identity, of memory, and of decor beyond the everyday.

10) Speculation: Is this brush set a copy of a brush set made of more expensive material, or does this set incorporate a variety of motifs and design elements that were popular at the time? How common was it to incorporate sea and flower designs into the same brush set? Is there a connection between class and the thickness of bristles?

| To see this picture please have your password ready and follow this hyperlink LOGIN |

1) Material: This set includes a hairbrush and a clothes brush. The backs are made of silver, the bristle plate is made of wood and the bristles are made of hog's bristle. To look at only the hairbrush, the neck's end points downward, then thins out and moves into a bulge as it nears the brush head. The bulge is terminated by three circular bands that are raised above the neck itself. The middle band is the largest and the highest, and the two bands beside them are of the same size and height. The back of the brush continues with the border of one large ledge and one small ledge but the brush back does not bulge as does the neck. Near the handle the brush has a box shape, but it enlarges as the head extends. At the top of the head there are three rounded points, not unlike those of the previous brush, but stylized so that they appear to be square. Carved into the back is a lined pattern that extends from the top of the head towards the handle but it stops at the three bars. In the centre of the line pattern is a diamond shaped stylized-leaf motif accented by the engraving of the letter 'C'.

The clothing brush is quite similar to the hairbrush, it has the same border pattern as the head of the brush, the same lined pattern, and the same engraved 'C'. The difference between the clothes brush and the hairbrush lies mainly in their shapes. The clothes brush is more oval in shape, while the hairbrush is a stylized rounded square. The clothes brush also has a stylized crown on both of its ends, but the points are rounded so that they appear more like petals then points.

2) Construction: The length of the hairbrush is 26 cm, the length of the neck is 13.5 cm, and the length of the head is 12.7 cm. The width of the tail on the neck is 0.7 cm, the thin area before the bulge is 1.6 cm, and the middle of the bulge is 1.8 cm. The width at the base of the head is 5 cm, the mid section of the head is 6.7 cm, the two outer points of the crown are 7.3 cm in width and the centre point of the crown is 6.4 cm. The clothes brush is 18 cm in length, and 5.5 cm in width at its largest point. The width of each of the outer crown points is 3.3 cm and the width of the middle crown point is 2 cm. The brush bristles of both the hairbrush and the clothes brush are 2.5 cm in length, there is 3 mm of space on either side of the bristle bunches, and there are 35-40 bristles in each bristle bunch. The bristles vary in length slightly but none are over 2 mm shorter than the others. When one looks straight down at the bristles of the hairbrush the brush looks quite full, but rows of bristle clumps can still be observed. The boor hogs bristles are fairly flexible, and they penetrate the hair very little, instead they move over the hair.

The hairbrush was assembled in eight stages: the back was molded, the bristle plate was cut, the bristles were cut, the bristles were tied into the bristle plate, the bristle plate was glued to the brush, the handle was molded and soldered to the brush head above the third band, the lines and the diamond shape where engraved into the back, and the 'C' was engraved perhaps at a later point. The quality of workmanship involved in these brushes is quite high. The edges where the silver meets the wood bristle plate are finished, the bristle holes are just large enough for the number of bristles that they contain, and one can only slightly observe the soldering done at the top of the neck of the hairbrush. The high quality of workmanship does not necessarily indicate that it is not mass-produced. The author recalls seeing an identical brush with a different letter engraved at a different person's home. The marks on these brushes say "sterling 925", which confirms that the brushes are solid silver rather than silver-plated. Below the sterling marking is a stylized capital 'X' with a bull facing towards the 'X' whose tail arches over its back. This indicates that the brushes were made in London in 1892 according to the Guide to Marks of Origin on British and Irish Silver Plate (1968).

The brushes have geometrical lines imprinted on the back in an ordered pattern of spaces and lines. The series of lines on the ladies brush follows this sequence: 4 tightly adjacent lines, small space of 2 mm, 11 adjacent lines, small space, 2 adjacent lines, large space of 4 mm, 2 lines, small space, 11lines, small space, 2 lines, large space, 2 lines, small space, 7 lines, small space, 2 lines, small space, 2 lines, small space. This series is identical for the second half of the brush. The clothing brush uses the same sequence of lines and spaces beginning at the large space of 4 mm and repeating the sequence on both sides of the brush. The geometrical pattern of the brush indicates that it follows a neoclassical style. However, the stylized leaves and the curved edges represent a natural, or Rocco style.

3) Primary Function: Much of this section is repeated from the above methodology. The lady's brush was created in order to brush the oils of the hair evenly from end to end. One can tell this because the boor bristles bend over the hair, rather than penetrating into the hair as one brushes. Victorian ladies brushed their hair one hundred times to make it smooth and shiny before they went to bed at night. A lady was to use the brush primarily on the hair that grows from the top of the head, rather than the underside hair which grows from the bottom of the scull and the neck. Due to the large size of the head of the brush, it is difficult to manipulate the brush so that it can reach this under-hair. The ridges on the brush's handle allow for a firm grip when brushing one's hair.

The clothes brush was used to brush lint off of clothes before one leaves the bedroom or the house. The width of the clothes brush was wide enough for a lady to grip comfortably. The ledges on the side of the brush allowed for a firm grip, and one's fingers could bend around the ledge to the wood bristle plate. Since the clothes brush has no handle, it was probably used only for the surface of the clothing. It would be difficult for a lady to manipulate the brush to reach the underside of her clothing. The brush under observation contains some lint, and the bristles have remained the same blond colour as the hairbrush's bristles. Considering that the bristles have not changed colour or degenerated, it can be assumed that the clothing brush was used to remove lint that was acquired in the home, and not for vigorous brushing that may have been required for dirt which was brought from outside.

4) Unintended functions: The secondary function of the brush set was as display items in the home. For the past two generations these items have sat, initials-up, on vanities. This demonstrates wealth visitors in the woman's bedroom. The set also indicates a preoccupation with beauty culture, and appearing as a lady, because not all classes had the leisure time to ensure that their clothes were free of lint and their hair was shiny from end to end. This particular brush set has also been used as a bond between women, and simultaneously as an indication of breaks within the family. Please refer to the provenance section for more information.

5) Provenance: As stated earlier, the brush set was made in 1892 in London by a company that worked with silver plate. The manufacturers created many of these brushes, as the researcher has seen an identical set with a different letter engraved at a home in Toronto. From this it can be deduced that the brushes were made for export to Canada, and that they were either made to order with an initial, or that they could be bought without an initial which could later be added by the buyer.

The original owner of the brush set had a last name beginning in a 'C'. Although the researcher knows the last name in question, the brush set is under dispute in a family, and the current owners would prefer that the particular names and locations of the brush remain secret. The original female owner lived in South Western Ontario, as did the preceding two owners. The brush set was acquired in 1892 at which time it had the initial 'C' which referred to its owner. The first owner, Mrs. C1, was married and had children, the number and gender of these children was not known to the current owner. The brush set was then given to a daughter-in-law, Mrs. C2. The date, or the life event, that precipitated this gift remains unclear to the current owners. Mrs. C2, lived from approximately 1915 to 1980, and had one daughter with Mr. C. Mrs. C2 married a second time after her husband died. The second marriage was to Mr. X. Two sons were born to this marriage. The brush set was given to the wife of the first son, or Mrs. X, shortly after his marriage in 1973. The son assumes that his mother purposely gave the brush set to his wife because she did not want her daughter, Mrs. C3, to have the set. The only female descendent of the 'C' line would like to acquire the brush set and is in friendly dispute with the current owner. The current owner, having the last name 'X', intends to replace the 'C' initial with an 'X'. This action would negate the origin of the set, and reaffirm the bond between the 'X' mother-in-law, and daughter-in-law. The action would also metaphorically erase the 'C' marriage, thereby breaking a bond between mother and daughter. The change in initial will also insure that the brush will remain in the 'X' line. The brush set may have served a similar function in an earlier transfer, depending on if there were girls born to the original 'C' family. This first transfer was one between a mother-in-law and sister-in-law, which may have broken a bond between mother and daughter.

6) Significance: The first two owners used and displayed the brush set to affirm their roles as upper middle class ladies. As was noted earlier, Victorian and Edwardian ladies were required to have shiny, neat hair. The brush under study created this type of hair due to its bendable and full bristles, the previous brush, however, had tougher, less abundant bristles. Brushing with these two brushes may have resulted in a different texture of hair. As reviewed in the symbolism section, the texture, colour, and shine of a woman's hair helped to indicate her class and purity. An astute Victorian was said to be able to read a woman's identity through her hair and therefore it became important to own the correct type of brush to create the desired hair type. Since brushes were frequently used as display items, perhaps Victorians read the class of brushes as well as reading the class of hair.

For Mrs. C3 and Mrs. X the meaning of the set has altered from the meaning given to the brushes by the previous two owners. To these two women, the set has become a family heirloom. The set remains displayed as an indication of the affluence of the family line, but the brush is unused. The meaning of the set is now one of memory of the generations past, and of family bonds, and family breaks rather than of Victorian femininity.

7) Design: This brush set used the traditional materials of silver, boor's bristle, and wood. The materials and the function of the set were not considered new by its Victorian owners, therefore the set did not use a futurism, utopian, or archaic model.

8) Verbal Expression: Words that describe the brush are the same words used to describe human anatomy. For example, people and brushes both have heads, necks, and backs. These human descriptors applied to brushes are indicative of the importance of the brush in making females appear as socialized women. Furthermore, by using natural or humanistic words to describe the brush, the social aspect of brushing one's hair becomes hidden. If brushing the hair is an everyday practice that reinforces one's class status, the naturalization of the brush extends to a naturalization of the act of brushing, thereby negating the idea that class is a performance. In other words, the act of brushing one's hair is a way of policing the boundaries between classes. However, this active class manipulation becomes naturalized through the use of humanistic words for the brush, and the hidden practice of hair brushing in the bedroom.

9) Symbolism: This section is repeated from the above methodology. Hair was to be brushed one hundred times before a Victorian woman went to bed. This was said to even out the oils of the hair making it shine. Hair brushing was part of a beauty ritual that confirmed high birth. Victorians had various fairytales that confirm the connection between hair and class. For example, The Goose Girl was the story of a princess that traveled to marry a prince from another kingdom that she had not yet met. On the journey, her maid took her place and forced the princess to become a goose girl while the maid married the prince. Later, the king saw the goose girl's beautiful shiny blond hair and realized that she was royalty (Gitter 939).

The brushing of one's hair in public was considered to be an indication of sexual availability (Gitter 938). Tidiness of hair also indicated one's sexual availability. Victorian novels frequently describe women's hair when explaining her character, the governess and the loyal wife had well groomed hair, while the unfaithful, passionate woman had ill-kept, messy hair (Miller 91). The colour of a woman's hair was also indicative of her sexuality; the blond was cool and pure, while the dark haired woman was passionate and erotic (Miller 91). There was also a strong connection between hair combing and the spinning of thread (Gitter 939). These were both considered to be woman's work. The hair and the thread sometimes combined to create a textile that helped to confirm family solidarity, but at other times hair and thread combined to create a web that brought the family's downfall.

In the above examples, the woman's hair is a receptacle for her hidden identity. Affluent Victorians kept a hair safe on their vanity where they placed the hair that came out in brushing and combing. This hair could then be used for jewellery, to create collages that went in frames, or as ornamentation in snuff boxes, and other display cases. Hair and the practice of hair brushing was a very important element of the everyday life of Victorian women. Hair combing took on meanings of identity, of memory, and of decor beyond the everyday.

10) Speculation: Why was hair and hair brushing spoken about so freely in Victorian society if it was considered to be a private matter? Remember to consider that women have different types and textures of hair. Therefore, the different brushes may have had the same final appearance for women with different hair. Did Victorians have myths about curly versus strait hair? At what point did hair brushing move from in front of the vanity to the washroom?

| Methodology |

|

Annotated Bibliography |

|

Second Term Plan |