Introducing Augustine

St. Augustine has been the most influential of all theologians in western Christianity. (He's much less influential — in fact, seldom even read — in eastern

Christianity. Similarly, writers who are considered giants in eastern Christianity, such as Maximus the Confessor, are seldom read in the west.)

St. Augustine has been the most influential of all theologians in western Christianity. (He's much less influential — in fact, seldom even read — in eastern

Christianity. Similarly, writers who are considered giants in eastern Christianity, such as Maximus the Confessor, are seldom read in the west.)

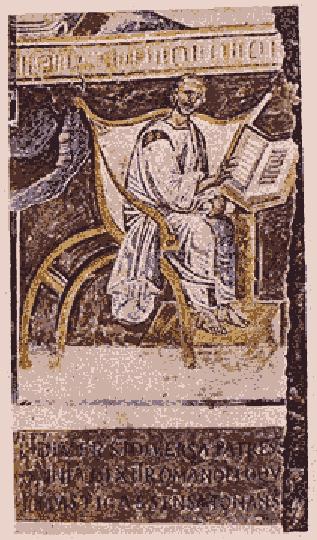

(At left is a sixth-century image of Augustine in the Lateran Palace, Rome. It's the oldest sursviving portrait of Augustine. From James O'Donnell's website.)

The Garden of Milan

González in his Story of Christianity begins by narrating one of the best-known episodes in Augustine's life, for which the source is Augustine's Confessions, Book 7. Augustine's worldly career has peaked early. In his late 20s, he is already the Imperial orator, living comfortably n the western capital of Milan with his concubine and son. But the external trappings of success are masking a profound spiritual struggle that he's experiencing inside. Who is he, really? And who is his god? Above all, should he accept Christ? Many months pass. One afternoon, in the late summer of 386, he seeks solitude in a garden, to reflect on weighty matters. He's startled by a voice (the voice of a child next door? an angel's voice?) saying, "Tolle, lege; take and read." Remembering how St. Antony's life was changed by an apparently random verse of Scripture that he happened to hear, Augustine opened his Bible to a verse from Paul: "Put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to fulfil the lusts thereof." González, like a great many writers, takes this as Augustine's "conversion."

But Augustine himself doesn't identify it as a moment of conversion to faith. Some say that its result was to trigger his decision for a celibate religious life away from the attractions and temptations of the world. Before very long, he would quit his job, put away his concubine, move back to North Africa, and found a monastery on family property.

Baptism by Ambrose

First, however, he chose to be baptized. He had long been struggling with whether to make this commitment. About nine months after the incident in the garden, Ambrose, bishop of Milan, himself one of the really significant theologians and leaders of early western Christianity, baptized Augustine. Here's a fresco of that event by Benozzo Gozzoli, who in 1465 finished seventeen frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Augustine around the choir of the Church of Saint Augustine in San Gimignano, Italy.

Episcopacy

Augustine was content to be a monk in North Africa, but one day, visiting the seaport town of Hippo (now Hippo Regius, Algeria), he found himself made the assistant bishop of the diocese, in line to succeed the diocesan bishop. Below to the left you'll find a picture of Hippo Regius today, with the remaining foundations of Augustine's basilica in the foreground. It's posted at James O'Donnell's website (see the links at the left); O'Donnell took pictures when he attended an Augustine conference in Algeria in April 2001. "If we learned nothing else on this trip so vividly," he writes, "it was that Augustine's world was one that could delight the senses in many ways."

As bishop Augustine kept to his monastic discipline as much as he could, mentored future leaders, and attended to the pastoral, liturgical, teaching, and administrative duties of his office. But he was also prominent in the affairs of the western Church in general. He weighed in on controversies, published numerous theological works, kept up a wide-ranging correspendence, and made efforts to influence state religious policy. In regard to the last, he has been criticized in modern times for his intolerant efforts to suppress the schismatic North African Christian group called the Donatists. (He justified his use of force to bring heretics into the Catholic Church on the basis of Luke 14:23, "Then the master said to the slave, ‘Go out into the roads and lanes, and compel people to come in, so that my house may be filled."

Why read the Confessions?

Here are some reasons. It's a  truly profound, wise, and beautifully crafted work of Christian testimony, theology, and devotion, one of the very greatest classics of Christian literature, or for that matter of world literature. It's essential reading for a theologically educated person. It's had a huge influence on both the Roman Catholic and mainline Protestant traditions. For better or for worse, it has often served as a template for our search for God (or God's search for us). It gives us by far the most intimate portrait of the inner life and

spiritual journey of any person, Christian or otherwise, in the ancient world. It became a model for personal Christian testimony in the west.

truly profound, wise, and beautifully crafted work of Christian testimony, theology, and devotion, one of the very greatest classics of Christian literature, or for that matter of world literature. It's essential reading for a theologically educated person. It's had a huge influence on both the Roman Catholic and mainline Protestant traditions. For better or for worse, it has often served as a template for our search for God (or God's search for us). It gives us by far the most intimate portrait of the inner life and

spiritual journey of any person, Christian or otherwise, in the ancient world. It became a model for personal Christian testimony in the west.

The purpose of the Confessions

The term "confession" in English, and even more clearly in Latin, has three possible meanings: owning up to guilt, acknowledging God's greatness, and affirming the words of faith. These are the themes of Augustine's Confessions. The whole of it is addressed directly to God. His opening words confess God's greatness in the words of Psalm 48:1: God is great, and worthy of praise. The book holds up the love and wisdom of God, and seeks to know and to offer the appropriate human response.

Why did he write the book?

No one really knows, and there are many theories.

- Perhaps he just wanted to make sense of his life for himself and others, as people often do who write autobiographies.

- Perhaps he was offering an example of the process of conversion, with all its ups and downs, for those seeking God..

- Perhaps he was writing a theology in autobiographical form.

- Perhaps he was responding to the criticisms aimed at him by his contemporaries, who were suspicious that this man who just a few years earlier had been notoriously anti-Christian was now a bishop.

- Perhaps someone asked him to write it.

- Perhaps he conceived it as apologetics, an attractive and persuasive presentation of Christianity to people in some of the non-Christian groups that Augustine himself had formerly frequented.

One of the puzzles in figuring out Augustine's purpose in writing the Confessions is that in Book X he moves abruptly out of autobiographical mode into to theological and Biblical reflection. Is that a clue to his purpose? Or did he have two purposes?

Other Major Works

Apart from the Confessions, Augustine wrote a host of works that were to prove foundational to all later Western theology, including the following:

Apart from the Confessions, Augustine wrote a host of works that were to prove foundational to all later Western theology, including the following:

- Sermons

- Commentaries

- City of God, depicting the differences and interconnections of two histories, human history and divine history, with probing attention to several important theological issues.

- Anti-Pelagian writings, countering a writer who underestimated the corruption of human will, and therefore underestimated the necessity of divine grace.

- Anti-Donatist writings, countering writers who understood the Church as a household of saints, not as a hospital for sinners, which was Augustine's understanding.

- Anti-Manichean writings, against an Eastern-based religion that taught a cosmic dualism; Augustine himself had been attracted to this movement in ihs younger years.

- On the Trinity, a probing and strangely inconclusive treatise on this foundational Christian doctrine.

- Enchiridion, a handbook of basic Christian doctrine.

- Various other philosophical and theological studies.

Augustine remains a respected celebrity in Algeria, Christian though he was, as this stamp shows.