Why study this?

Readers of González' Story of Christianity will note that he devotes only three or four pages to this topic. From one point of view, that's a justifiable choice: few Christians lived in Britain in the first few centuries, its impact on early Christianity was small, and its major theologian, Pelagius, was a heretic, whose main contribution was to provoke Augustine into correcting him. But those who are in church traditions which have grown out of English Christianity may have understandable reasons of their own for studying Christian Britain. And Patrick, whom we read for this course, is a genuinely fascinating character.

Bede

Bede, an extremely learned monk in the unlikely situation of medieval Northumbria, finished his "Ecclesiastical History of the English People" in CE 731. His use of valuable sources, his balanced judgment, his warm sympathy for most of the people he writes about, his readable and engaging style, and his persuasive presentation have made him an extremely influential interpreter of English Christian history. He is the most important, and most unescapable, single historical source for Christianity in Great Britain before Bede. His historical work has shaped the historical identity of England and the character of English Christianity. His great vision was that England was a unified people despite its political divisions, since it was bound by a common faith rooted in the authority of Rome.

One of Bede's most significant contributions to historiography was his use of BC/AD (BCE/CE) dating, a system that he didn't event but which he established permanently. Before him, dates were given as a regnal year of a monarch or other important personage.

Christianity in Roman Britain

The island which the Romans called “Britannia” was home to "the British," a Celtic people who were dominant in the southwest regions. The Celts in the ancient world were a far-flung people, possibly originating in what's now Switzerland, but stretching from Ireland to a number of places signalled by later place-names cognate with the word "Celt": Wales (French Galles,) Galicia (in Spain), even Galatia (in Asia Minor), which we know from the letters of Paul.

The island which the Romans called “Britannia” was home to "the British," a Celtic people who were dominant in the southwest regions. The Celts in the ancient world were a far-flung people, possibly originating in what's now Switzerland, but stretching from Ireland to a number of places signalled by later place-names cognate with the word "Celt": Wales (French Galles,) Galicia (in Spain), even Galatia (in Asia Minor), which we know from the letters of Paul.

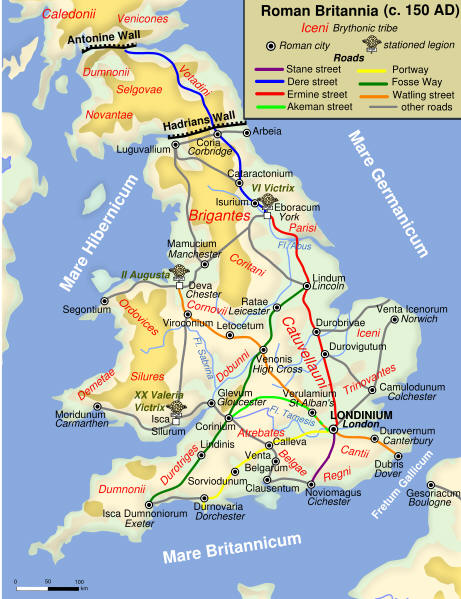

Julius Caesar invaded the island in BCE 55, and over the next ten or fifteen years it came under the control of the Roman Empire. Romans were great at building infrastructure like road systems, aqueducts, and public buildings; so cities and systematic commerce developed, and Roman and British populations mixed. North of a certain line — marked by the Emperor Hadrian’s famous wall, parts of which can still be seen (and walked along) in northern England — Roman rule did not extend.

The map to the right is made available under a Creative Commons licence from World History Encyclopedia.

Legends of early Christianity in Britain

Jesus visited Britain: This story apparently originated with Robert de Boron (fl. ca. 1300). He said that Joseph of Arimathea, a tin merchant, traveled to Glastonbury on business, and took his young friend Jesus with him. The legend is echoed in the first words of the anthem "Jerusalem" with words by William Blake: "And did those feet in ancient times / Walk upon England's mountains green."

The ten lost tribes of Israel found their way to Britain: this has been the tenet of the British Israel societies.

The chalice at the Last Supper came to Britain. In this story, Joseph of Arimathea used it to collect Jesus' blood at the crucifixion, and later brought it — now called "the Holy Grail" — to Britain. The grail got lost at some point, and King Arthur's knights went on a quest for it.

Early Christian evidence

There are a very few references to Britain in early Christian literature (Origen, Tertullian, Athanasius, Jerome), suggesting that although there were indeed Christians in Roman Britain, perhaps as early as CE 200, Christian leaders in the Mediterranean Church were only vaguely aware of them. How Christianity first came to Britain, and what early Britain Christian communities were like, we don't know. The first Christian martyr there, Alban, may have died in the Decian persecution around 250 (but some say it was about 208, and others think it was after 300, and still others think that Alban is a legendary figure). In later centuries the shrine of his martyrdom inspired the location of St. Alban’s Cathedral, north of London.

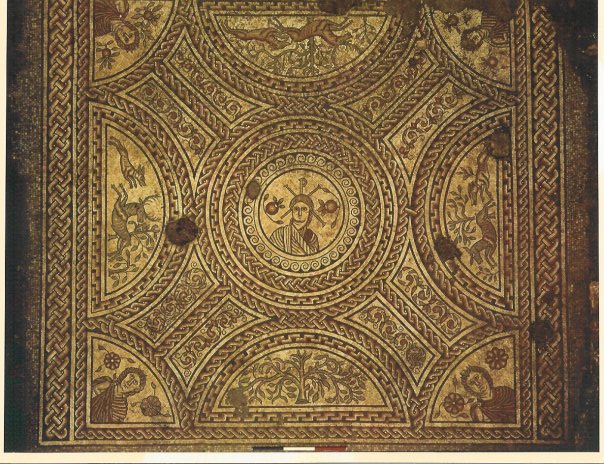

Over the past century or so archaeological excavations in various parts of what's now England have unearthed early liturgical silver, wall plasters, and floor mosaics  with Christian motifs, suggesting that at least some Christians in Britain were wealthy. Some of these treasures are on display in the British Museum in London. An example is the floor mosaic, pictured left, from the early fourth century; its central figure is thought by many to be Christ. A chi-rho monogram (from the first two Greek letters in the name "Christos" is behind the head; pomegranates, which in early Christian iconography represented the seeds of faith, flank it. This is from Hinton St. Mary, Dorset.

with Christian motifs, suggesting that at least some Christians in Britain were wealthy. Some of these treasures are on display in the British Museum in London. An example is the floor mosaic, pictured left, from the early fourth century; its central figure is thought by many to be Christ. A chi-rho monogram (from the first two Greek letters in the name "Christos" is behind the head; pomegranates, which in early Christian iconography represented the seeds of faith, flank it. This is from Hinton St. Mary, Dorset.

The decline of Christian Roman Britain

In about A.D. 406, as barbarians were ravaging the Empire, the Roman army appears to have been called away from Britain to more strategic places, and the Roman period in British history then ceases. There are two principal theories as to what happened next. One is that the British invited Germanic barbarians to defend them, and the would-be defenders wound up conquering them instead. Prominent among these barbarians were Angles and Saxons, and so “England” (Angle-land) was born. The British had to flee to the west and the south, and became the Welsh (in what is now Wales) and the Bretons (in what is now France). Stories told by early British and English historians favour this view, called the "catastrophic" theory. The second theory is that there was a more gradual infiltration of Germanic peoples into Britain, with intermarriage and cultural fusions. The archaeological evidence favours this view, showing, as it does, cultural overlaps in the same areas over a period of time. This period (spanning the fifth century) is a “dark age” for which little firm evidence has survived.

Celtic Christianity

Ireland

The "apostle to Ireland" is considered to be Patrick (fl. 430s?), although his own writing makes it clear that when he arrived there, Christianity was already planted.  He was raised a Christian on the west coast of Great Britain in the late fourth or early fifth century. The main evidence for his life is his Confession, which we’re reading in class. Patrick's narrative is often unclear, and some of its details seem inconsistent, so it’s very hard to piece together his biography. Generally, his story is that he was kidnapped by pirates or raiders in Britain and sold into slavery across the Irish Sea in Ireland, and although he was able to escape, he felt called to return as a Christian missionary or minister. By his account, he had a very successful ministry, although he had many Christian critics.

He was raised a Christian on the west coast of Great Britain in the late fourth or early fifth century. The main evidence for his life is his Confession, which we’re reading in class. Patrick's narrative is often unclear, and some of its details seem inconsistent, so it’s very hard to piece together his biography. Generally, his story is that he was kidnapped by pirates or raiders in Britain and sold into slavery across the Irish Sea in Ireland, and although he was able to escape, he felt called to return as a Christian missionary or minister. By his account, he had a very successful ministry, although he had many Christian critics.

Scotland

Pretty well contemporary with Patrick was Ninian, a bishop in North Britain. His cathedral is supposed to have been located at Whithorn, in the Galloway district of what's now Scotland. There were no Scots there at the time; the area was inhabited by people that the Romans caled Picts, a partly Celtic people. The early story is that Ninian evangelized them and established a Christian church among them.

Columba

CAmong the early Celtic Christians of Ireland, the best known, after Patrick, is Columba (ca. 521–ca. 597). His “life” was written about a century after his death by a monk named Adamnan, but it isn’t considered overly reliable. Columba founded monasteries in Ireland and then, for one reason or another, left (was exiled? was forced to leave? escaped some kind of problem?), and set up a monastery on the island of Iona off northwest Scotland. (This island is today a Christian pilgrimage centre.) From Iona, Columba and his monks evangelized the northern Picts.

The character of Celtic Christianity

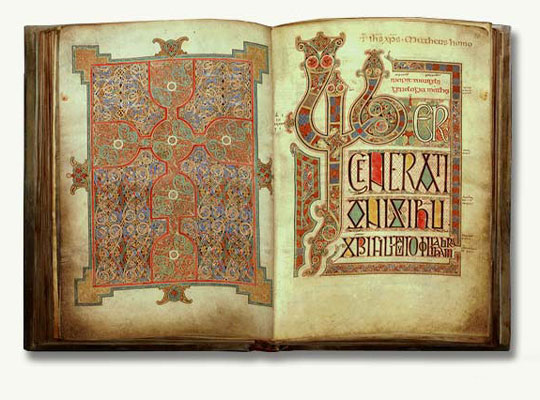

The Celtic Christianity of west Britain, Ireland, and Scotland had a reputation for the love of Scripture, asceticism, poetry, love of nature, the copying of manuscripts, beautiful manuscript art, Biblical scholarship, and evangelism. It was distinct from Roman Christianity in several respects, including its date of Easter, its “tonsure” or haircut for clergy, and its non-diocesan church order. In the seventh century Celtic Christians began to have an increasing impact on western Christianity through their missionaries and scholars. They also developed a penitential system (for the confession of sins, penance, and absolution) which became one of the fundamental realities of Christian life in medieval western Europe.

Early Celtic Christianity is perhaps best known for its magnificent manuscripts. To the right is pictured a Chi-Rho from the Book of Kells, completed around CE 800. It's displayed at Trinity College, Dublin.

Anglo-Saxon Christianity

Celtic influences

It appears that the Roman British Christians didn't convert the Anglo-Saxons when the latter came into England in the fifth century. The Anglo-Saxons were therefore largely converted by missionaries from abroad. One set of missionaries came from Ireland, by way of Columba's monastery  of Iona, and thus from the north. The most notable of these Irish ministries was Aidan (d. 651), who at the invitation of Oswald, the king of Northumbria in northern England, set up a monastery and missionary centre on the island of Lindisfarne around 635. Other missionaries from Lindisfarne were Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (ca. 634–687), Cedd (ca. 620–664), Chad of Mercia (d. 672), and Wilfrid bishop of York (d. ca. 710). Stories of the great Celtic saints and missionaries to northern England were told a century and a half later by a great northern English scholar the Venerable Bede, in his important and influential Ecclesiastical History.

of Iona, and thus from the north. The most notable of these Irish ministries was Aidan (d. 651), who at the invitation of Oswald, the king of Northumbria in northern England, set up a monastery and missionary centre on the island of Lindisfarne around 635. Other missionaries from Lindisfarne were Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (ca. 634–687), Cedd (ca. 620–664), Chad of Mercia (d. 672), and Wilfrid bishop of York (d. ca. 710). Stories of the great Celtic saints and missionaries to northern England were told a century and a half later by a great northern English scholar the Venerable Bede, in his important and influential Ecclesiastical History.

(To the left: St. Martin's cross, on the island of Iona, was sculpted from a single slab of rock between CE 750 and 800; one side is carved with scenes from the Bible.)

(Below to the right: monks at Lindisfarne in the early 700s copied out a beautiful illuminated (illustrated) Bible manuscript known as the Lindisfarne gospels.)

Roman inflences

The second set of missionaries to England came from Rome, and thus they evangelized from the south. They were sent by Pope Gregory the Great. The first mission leader was named Augustine, called "of Canterbury", who arrived in 597. (This Augustine is of course different from the North African Augustine discussed on the previous webpage.) He arrived in Kent, in southwest England, and was welcomed by King Aethelberht, whose wife Bertha was a Christian from Gaul. The king was converted, gave the missionaries a monastery at Canterbury, and allowed them to preach. Augustine became the first archbishop of Canterbury, and founded other bishoprics at London and Rochester.

Synod of Whitby

With Celtic Christianity spreading through England from the north, and Roman  Christianity spreading through England from the south, the two styles were bound to come into conflict. At a monastery at what is now called Whitby (then Streonshalh) in Northumbria, representatives of Roman Christianity argued their case before King Oswiu of Northumbria against representatives of Celtic Christianity. (The head of the monastery — a double monastery of men and women — was Hilda of Whitby [614–680)], an energetic leader of royal blood.) The king sided with Rome, mainly on the grounds that it had been the see of Peter, the chief of Jesus' disciples. This event was later reported by Bede as the victory of Roman Christianity in England, although in fact the Celtic style continued in many places for several centuries thereafter.

Christianity spreading through England from the south, the two styles were bound to come into conflict. At a monastery at what is now called Whitby (then Streonshalh) in Northumbria, representatives of Roman Christianity argued their case before King Oswiu of Northumbria against representatives of Celtic Christianity. (The head of the monastery — a double monastery of men and women — was Hilda of Whitby [614–680)], an energetic leader of royal blood.) The king sided with Rome, mainly on the grounds that it had been the see of Peter, the chief of Jesus' disciples. This event was later reported by Bede as the victory of Roman Christianity in England, although in fact the Celtic style continued in many places for several centuries thereafter.

Synod of Hertford

This council, called by Theodore, a very able archbishop of Canterbury who hailed from St. Paul's town of Tarsus, addressed a number of administrative issues, and is sometimes regarded as the origin of the Church of England as an institutional entity.