Church Planting Outside the Roman Empire

For the second edition of The Story of Christianity, Justo González added Chapter 25, "Beyond the Borders of the Empire." Yes, he had his reasons in the first edition to focus pretty exclusively on the Mediterranean world, partly because that's where most Christians were, and partly because so many of his western Christian readers trace their roots to early Mediterranean Christianity. But the Church had expanded beyond Roman Imperial borders.

Every area has its story of Christianization. The following places are among the most prominent.

India

Many Christians in India trace their church to the ministry of the apostles Thomas (the "doubting Thomas") and Bartholomew. There's some corroboration from fourth-century Christian writers in the fourth century (notably Eusebius and Jerome) that St. Bartholomew made his way to India. Otherwise the first likely major Christian teacher there was Pantaenus (d. ca. 200), the head of the great Christian school at Alexandria, who, however, when he arrived, found Christians already there, using the Gospel of Matthew. (See Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 5.10. Here's a link to book 5; look down at chapter 10!) Numerous Christian immigrant settlers in the fourth century added to the numbers of the Christian community there.

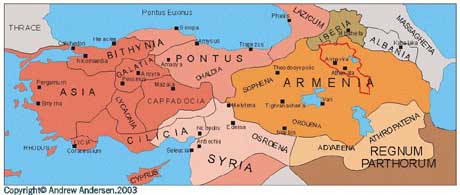

Armenia

Armenia is strategically located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and was politically situated between the Roman and the Persian Empires. The Church in Armenia traces a Christian presence to the first century, but things changed around the year 300. According to one version of the story, a beautiful Christian virgin named Rhipsime, who with a group of nuns was threatened by Diocletian, sought refuge in Armenia. Unfortunately, King Drtad (or Trdat or Tiridates) III of Armenia took an unholy sexual interest in her. She fought him off with the power of Christ, and temporarily escaped — but was recaptured, tortured, and executed. The king went insane. Meanwhile, St. Gregory the Illuminator (c. 257—c. 331), an Armenian who was raised in Cappadocia, had been imprisoned in a pit in Armenia for refusing to worship a local goddess. After several years he was released, the story goes, thanks to a vision which the king's sister had received. On Gregory's release he successfully evangelized King Drtad; a principal strategy was to remind him of the prayers and preaching by which Rhipsime had attempted

Armenia is strategically located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and was politically situated between the Roman and the Persian Empires. The Church in Armenia traces a Christian presence to the first century, but things changed around the year 300. According to one version of the story, a beautiful Christian virgin named Rhipsime, who with a group of nuns was threatened by Diocletian, sought refuge in Armenia. Unfortunately, King Drtad (or Trdat or Tiridates) III of Armenia took an unholy sexual interest in her. She fought him off with the power of Christ, and temporarily escaped — but was recaptured, tortured, and executed. The king went insane. Meanwhile, St. Gregory the Illuminator (c. 257—c. 331), an Armenian who was raised in Cappadocia, had been imprisoned in a pit in Armenia for refusing to worship a local goddess. After several years he was released, the story goes, thanks to a vision which the king's sister had received. On Gregory's release he successfully evangelized King Drtad; a principal strategy was to remind him of the prayers and preaching by which Rhipsime had attempted  to convert him. The King now finally made a commitment to Christ, and decreed in 301 that Christianity was to be the state religion in 301. Armenia thus became the world's first Christian country. Here's an English translation of an early hagiography of St. Gregory.

to convert him. The King now finally made a commitment to Christ, and decreed in 301 that Christianity was to be the state religion in 301. Armenia thus became the world's first Christian country. Here's an English translation of an early hagiography of St. Gregory.

The role of captive women missionaries

Andrea Stark of the University of Utah, in Church History 79 (2010): 1–39, linked in the left-hand column, observes that, despite the "romantic ring" of the claim, in fact "hostages, slaves, and prisoners of war" have been crucial in spreading religions and cultures. Rhipsime, discussed above, and represented in the picture at right, is one of her case studies. Another is an unnamed captive in Iberia, a term which now refers to Spain but which was the ancient name for Georgia (shown on the map above, just north of Armenia). Her story is told by a prominent ecclesiastic named Rufinus just after 400. Her devotion to Christ amazed her contemporaries, but even more did her healing miracles. She came to the attention of the Queen of Iberia, who was cured of a disease by the prayers of this Christian woman; and the king was subsequently healed of an episode of blindness by praying to the Christian captive's God. The king then sent to Constantinople for missionaries.

Theognosta (take the link and scroll down), another Christian virgin, was captured from a convent and given as a present to the king of Yemen, in southern Arabia. She impressed him and the people there with her ministry of healing. They sent to Constantinople to request a bishop to instruct them, but it was the prayers of Theognosta that were decisive in their conversion. She was also instrumental in converting the king of India.

The texts involved are historiographically tricky, and evidently include apocryphal elements, but Stark, the modern author, argues that they evidence an evangelization "from below" by simple but inspired women on the east Roman frontier who knew their Scriptures, and were committed in their discipleship.

Dura-Europus

The earliest of known church buildings, a chapel in a Roman fort on the eastern border, was mentioned on the "church order" webpage for the course. It was evidently built to serve the religious needs of Christian soldiers at this outpost intended to defend the Empire from the Persians. It's perhaps an indication of another kind of "evangelization from below".

Persia

The beginnings of Christianity in Persia are obscure. Parthians are identified on the day of Pentecost in Acts 2, and the Parthian Empire ruled Persia at the time. One strong but unverifiable tradition is that the early evangelist of Persia was St. Addai of Edessa, identified as one of the Seventy sent out by Jesus. (He's also called Thaddeus, or Aday, or Aggai.) His name is paired with that of his disciple Mari in the ancient Liturgy of Addai and Mari, used in the East Syrian rite, which is remarkable among liturgiologists for lacking Jesus' words of institution ("this is my body...") in the Eucharistic prayer. The Parthian Empire had a reputation for tolerating minority religious groups, and Christians were evidently free of perssecution until the Parthian dynasty gave way to the Sassanian dynasty in 224. The sixth-century Chronicle of Arbela reports that around the year 200 there were more than twenty Christian bishops in Persia, and that there were Christians as far away as northern Afghanistan. For further information, here's a summary of some research by the late T.V. Philip, a former professor at the United Theological College in Bangalore, India. And here's a teaser about Philip's book East of the Euphrates: Early Christianity in Asia.

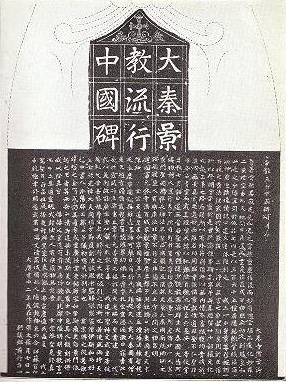

China

The first recorded ministry to China was Alopen in about 635. His name is known only from a stele (a standing stone slab) that was erected in 781 (pictured left) next to Chongren Buddhist Temple in Shengzhou, Shaanxi province. He came from the Church of the East in the Persian Empire, a non-Chalcedonian church considered Nestorian by the Orthodox churches. The Chinese emperor of the day, Taizong (Tai Tsung), considered one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history, and himself a great scholar, welcomed Alopen, according to the  stele, and took a great interest in the scriptures that he brought. The territory Taizong ruled was larger in extent than present-day China, and was the most populous and probably the strongest nation in the world. Within a few years, again according to the stele, the Church in Shaanxi had twenty-one priests and was officially protected; early books of Christian teaching in Chinese, called the Jesus sutras, date from this time. There's good reason to believe that Chinese Christianity and Tantric Buddhism influenced each other. Christianity apparently maintained its strength in China until the ninth century, but was a collateral victim of anti-Buddhist persecution in 845, and seems to have disappeared in the early tenth century, when the Tang dynasty ended.

stele, and took a great interest in the scriptures that he brought. The territory Taizong ruled was larger in extent than present-day China, and was the most populous and probably the strongest nation in the world. Within a few years, again according to the stele, the Church in Shaanxi had twenty-one priests and was officially protected; early books of Christian teaching in Chinese, called the Jesus sutras, date from this time. There's good reason to believe that Chinese Christianity and Tantric Buddhism influenced each other. Christianity apparently maintained its strength in China until the ninth century, but was a collateral victim of anti-Buddhist persecution in 845, and seems to have disappeared in the early tenth century, when the Tang dynasty ended.

The Goths

The Goths were a migrant east Germanic people among the northern "barbarians" who crossed the Danube in 238 and began taking plunder in Roman territory. In 251 they took captive a number of hostages, among whom were several Christian women, who entered Gothic society and brought their faith with them. Also, in their border location, many Goths increasingly participated in Roman society, where they encountered Christianity, and many were converted. Stresses developed, however, and Christianity was sometimes persecuted.

According to the fifth-century church historian Sozomen, the great missionary to the Goths was Ulfilas (Wulfila) (d. 383). Ulfilas was a Greek Cappadocian by descent, but was raised among the Goths, apparently because his grandmother, a Christian, had been taken captive. He converted numbers of Goths to Christianity. But, to complicate matters for the future, his brand of Christianity was Arian. He came to the attention of the Arian Eusebius of Nicomedia (not the church historian), who ordained him bishop, around 340, and sent him back to the Goths. Ulfilas created the Gothic alphabet in order to translate the Bible. The Gothic chieftain Fritigern also played a significant role in evangelization.