Why We Divide History Into Periods

Historians periodize the past: that is, they divide it into blocks of time, which they may call by such names as periods, eras, or ages. A period is a term of years with significant common characteristics, which, depending on the historian's interests, may be social characterstics, or political ones, or artistic, economic, technological, or religious ones, etc. The period begins when these characteristics become notable, and ends when they are waning. Some periods have obvious dates, such as the Elizabethan era, where the common element is that Elizabeth I was queen (1558 – 1603). Most periodizing, though, invites discussion. Art and music historians usually want to date the Baroque period , which is the period when the Baroque style of art held sway, from about 1600 to 1750, but others disagree, since the Baroque style has many elements and doesn't always appear purely, and because it didn't abruptly start and abruptly end. Some historical periods have different dates in different places. The Renaissance started in Italy well before it started in England; the Englightenment is usually dated much earlier in England than in France.

, which is the period when the Baroque style of art held sway, from about 1600 to 1750, but others disagree, since the Baroque style has many elements and doesn't always appear purely, and because it didn't abruptly start and abruptly end. Some historical periods have different dates in different places. The Renaissance started in Italy well before it started in England; the Englightenment is usually dated much earlier in England than in France.

Working with periods helps historians make useful (though never absolute) generalizations about them. These generalizations give them the historical contexts that help them understand the people, events, and social structures of the past. Periodizing also helps them think about the processes of historical continuity that gives a community, nation, or culture a sense of identity, and the processes of historical change that move a community, nation, or culture into different ways of understanding or doing things. And periodizing helps historians avoid anachronism, which means assume that something that's true of one period is also true of another.

Periodizing Christianity

For several centuries it has been common to divide western Christian history into three large periods (with many subperiods): early, middle ("medieval"), and modern. Historians don't agree, though, on how to date these periods. Here are some different views as to when the early period of Christianity ends:

- 313: The edict of toleration. The rationale is that the main theme of early Christianity was that it was shaped by its vulnerability to persecution; medieval Christianity will be shaped by its political privilege.

- 410 – 430: The sack of Rome by the Visigoths; the death of Augustine. González in Story of Christianity identifies these two events as representing "the end of an era" (the title of his chapter 26) and the beginning of "the new order" (the title of his chapter 27).

- 461: The death of Pope Leo the Great. The historian W.H.C. Frend on The Early Church regarded Leo's death as representing the transition from an early Christianity which was a predominantly lay movement to a medieval Christianity which will be dominated by clergy and characterized by clericalism.

- 476: The abdication of the last western Roman emperor. In one reckoning, this is the date of "the fall" of the western Roman Empire. It marks the transition of an early Christianity which is shaped by its negative or positive relations with the Roman Emperor to a medieval Christianity which is shaped by its negative or positive relations with post-Roman kingdoms.

- 604: The death of Pope Gregory the Great. For the Roman Catholic Church, Gregoroy is the last "Father of the Church." His death represents the end of the process of establishing the authoritative doctrinal formulas and traditions of the deposit of the substance of the Christian faith. Medieval and modern Christianities will be required to work within them.

- 632: The death of Muhammad and the beginning of the Calpihate ("caliphs" are the successors of Muhammad). This is the beginning of Islam as a global political-religious movement. Within a century, most of the territories of the Christian Empire of Byzantium have fallen to Islam, and the centre of Christian gravity moves west. In this interpretation, early Christianity is a religion dominated by the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean; medieval Christianity is dominated by the people of western Europe.

Late Antiquity

The historian Peter Brown, who has been mentioned on our earlier webpages, has been influential in establishing the period of "late antiquity" in historical writing. He argues against an abrupt transition from early to medieval, and in favour of a transitional period with elements of both, and differences from both. Late antiquity can be seen as a transitional time of creative adaptations to new geopolitical and social realities. Historical processes that dominate Late Antiquity include Christianization, church-building, clericalization, migrations and Germanization, and ruralization. Islam is a game-changer. The Christian centre of gravity moves from the east to the west, and from the Mediterranean to Europe.

As always, historians disagree on the dates for Late Antiquity. One way to date it is to begin with the Edict of Milan in 313 and end witih the Caliphate in 632. Some historians would rather keep the dates a bit fuzzy, since history isn't so terribly tidy.

The idea for a period of late antiquity arose in the history of art in the early twentieth century, to take account of the perception that the materials and styles of art for this time period are characteristically neither "early" nor "medieval".

Fragmentation of the Roman Empire

Here's a map from Lynn Harry Nelson at a University of Kansas website (http://www.vlib.us/medieval/lectures/justinian.html) showing how the barbarian invasions fragmented the western Empire. This represents the state of political divisions in the mid-sixth century. The eastern Empire ("the Byzantine Empire") remains under the (often nominal) power of the Roman Emperor (now ruling from Constantinople). The western territories are still claimed by the Roman Emperor in Constantinople, but the reality on the ground is that they are divided up into post-Roman kingdoms.

Important dates

- 313: the Edict of Milan legalizes Christianity and begins to reverse the effects of the Great Persecution.

- 325: the Council of Nicea is the first serious effort to structure an effective, politically supported central authority of the Christian Church, with unified doctrine and standards of discipline, under the authority of the Emperor.

- 380: the Niceno-Constanipolitan Creed is completed.

- 393: Theodosius proclaims a comprehensive law prohibiting public displays of any religion other than Nicene Christianity.

- 410: Rome is sacked by Alaric and the Visigoths.

- 430: Augustine dies, just before the Vandals invade North Africa.

- 476 : The last Roman Emperor of the West is deposed; rulership devolves to men of the "barbarian" (Germanic) races.

- 496 : Clovis, king of the Franks, is baptized a Catholic Christian.

- c. 524 : Boethius writes his Consolations of Philosophy.

- c. 530 : The Benedictine Rule is completed, and Benedictine monasticism begins developing into a significant cultural, social, political, intellectual, and economic force in Europe.

- 536 – 554: the Emperor Justinian attempts to reconquer the West.

- 565 : Columba evangelizes Pictland (Scotland).

- c. 587 : The Visigoths in Spain are converted to Catholic Christianity.

- 590 – 604 : Pope Gregory I (the Great) reigns.

- c. 593 : Gregory of Tours, an influential bishop and historian, dies.

- 597: Augustine ['of Canterbury'] arrives in Canterbury, which will be a base for the Roman evangelization of England.

- 622: Muhammad departs from Mecca and arrives with his followers in Medina (the Hijrah); a unified and self-confident movement develops; this is year 1 of Muslim calendar.

- ca. 635: Aidan arrives in Lindisfarne, which will be a base for the Celtic evangelization of England.

- 636 : Isidore of Seville dies.

- 649: The Lateran synod condemns monothelitism.

- 664: The Synod of Whitby (England) privileges Roman Christianity over Celtic Christianity.

- 680-681: The 6th Ecumenical Council confirms papal privileges.

- 698 : The Lombards adopt Catholic Christianity.

- 711: The Muslim conquest of Spain begins.

- c. 720 – 754 : Boniface evangelizes the Germanic peoples.

- 732 : The Battle of Tours (symbolically) ends the Muslim conquest of western Europe.

- 735: Bede writes his Ecclesiastical History of England.

- c. 751 : Ravenna falls to the Lombards.

- 769 : A Lateran synod is held with large Frankish representation.

- 794: the Council of Frankfurt is called by Charlemagne, and makes important decisions independent of the Eastern Church.

- c. 800: The Viking raids begin.

- 800: Charlemagne is crowned Emperor.

- 843: The Treaty of Verdun is agreed, dividing western imperial Europe into three large territories.

Benedict of Nursia (c. 480-c. 547)

Benedict's life story, according to traditions received, goes something like this. He was born into the nobility in the small Italian town of Nursia, and grew up in Rome. When he reached the age for higher studies, he found himself disappointed in love, revolted by the dissolute lives of his friends, and troubled by the influence of his family's wealth and privilege. He renounced his patrimony and set up a Christian community in an isolated church well outside the city, in collaboration with some Christian friends and a couple of servants. There he worked a miracle which gained him unwanted notoriety, and he became a hermit for three years. But many came to him for guidance; for them he built twelve monasteries, and became their abbot. The priest in the area was jealous of his success, and began harassing the monks; so Benedict moved to Monte Cassino, near Capua, where he built an oratory in an old temple of Apollo. Recognizing that sanctification normally comes not through a solitary life or an austerely ascetic life but through community, he wrote his Rule.

The Rule envisions a Christian life of laypeople in community based on the principle orare et laborare, pray and work. Any work compatible with Christian conviction and the Rule is allowed; notable examples are farming, teaching, and scholarship. Monks commit themselves to obedience. The Rule provides that monks will have sufficient food (though not red meat), clothing, and sleep. Six times of prayer are structured into the daily routine. The superior is elected by the monks, and has considerable authority. Important issues are discussed by the community. The Rule combines Gospel with romanitas (Latin cultural ideals).

Benedictine monasticism was extremely influential in the Western Middle Ages, and the Rule also influenced many non-Benedictine religious rules in the West as well.

Pope Gregory I (the Great)

Gregory (c. 540-604) is one of two popes called "the Great" (the other is

Leo), and one of four "Latin doctors of the ancient Church"

(the others are Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustine). He was born into the

patrician class and was reportedly extremely well educated. He was prefect

of Rome at about the age of 30. In about 574, after much inward struggle,

he gave up his worldly possessions and ambitions, and  became a monk. His

family estates in Sicily became monasteries. He may have followed the

Benedictine rule. Against his will, he was ordained one of the seven deacons

of Rome, and was sent as an ambassador to the court at Constantinople,

where he stayed six years. He entered into a controversy with the patriarch of Constantinople on the resurrection; the emperor ruled for Gregory.

When he was recalled to Rome, he returned with great joy to his monastery.

He served as an adviser to the pope, and on the pope's death, he was himself

elected pope by the clergy and people of Rome in 590.

became a monk. His

family estates in Sicily became monasteries. He may have followed the

Benedictine rule. Against his will, he was ordained one of the seven deacons

of Rome, and was sent as an ambassador to the court at Constantinople,

where he stayed six years. He entered into a controversy with the patriarch of Constantinople on the resurrection; the emperor ruled for Gregory.

When he was recalled to Rome, he returned with great joy to his monastery.

He served as an adviser to the pope, and on the pope's death, he was himself

elected pope by the clergy and people of Rome in 590.

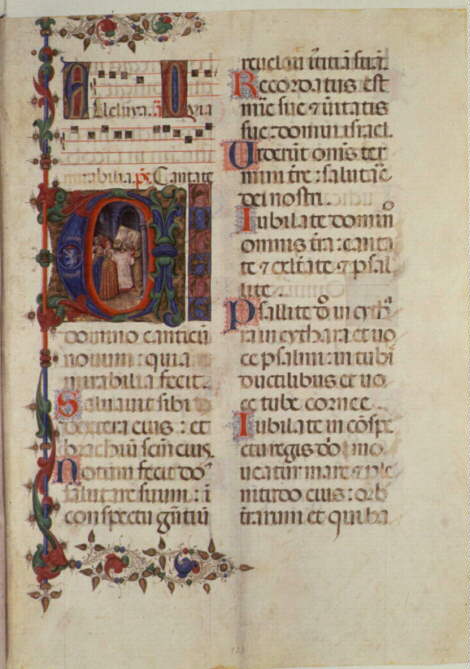

Almost his first act was to write his On Pastoral Care, on the duties of a bishop. In a time of great civil turmoil, he assumed considerable civil responsibility in Rome. Ecclesiastically, his vigorous administration, his claiming of authority over other western dioceses and even in the east, his sponsorship of missionary work, his reform of the liturgy, including possibly some elements of the music which came to be called Gregorian chant (as illustrated in the manuscript image to the right), and his influential theological, pastoral, and Biblical writings and sermons, have promoted his reputation as the founder of medieval Christianity.

Boethius

Boethius (c. 480-c. 525), an orphan, was raised in a wealthy aristocratic household. He was immensely well educated in both Greek and Latin literature. He made translations of Greek philosophy into Latin, wrote learned commentaries, and wrote school texts that were much used in the Middle Ages. In the 520s he served the Ostrogothic king Theoderic as a high official; the king suspected Boethius of disloyalty and threw him into jail, where he is supposed to have written his great work Consolation of Philosophy, which was very popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. He was then executed.