Christological controversies

From about 350 to 451, theologians and leaders of Eastern Christianity were absorbed in oftentimes fierce controversies about the relation of the divine and human natures in the person of Jesus Christ. In 451 the Emperor convened an ecumenical council at Chalcedon (now a district of the city of Istanbul, east of the Bosporus) which published a defining statement on the issue.. Like most conciliar statements, however, this one didn't solve the issue for everyone. Instead, it led to schisms which have never been healed. Thus the year 451 doesn't represent the end of quarreling, but a landmark turning-point. In modern ecumenical conversations many have concluded that the schisms weren't so much about theological differences as about the highly political and sometimes brutal way that the Byzantine Empire tried to enforce Chalcedon.

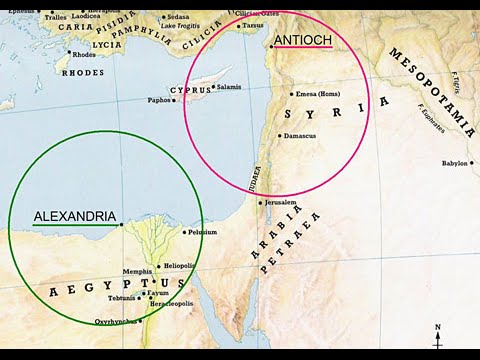

The parties to the dispute were all Trinitarians who agreed, against Arianism, that Christ was divine. The dispute was about the way in which the human and divine natures in the person of Christ were connected. The dispute is most easily introduced by adverting to our distinction between Alexandrian and Antiochene, notwithstanding the difficulties with representing these as clear opposites.

- Alexandrians, who em

phasized the spiritual understanding of Scripture, and were less interested in the Bible's historical details of the life of Jesus, emphasized the divine nature of Christ. Their opponents charged that Alexandrians neglected Jesus' humanity, and called them "monophysites" (one-nature thinkers), meaning that they seemed to acknowledge only the divine nature of Jesus. That charge was probably true of some extreme Alexandrians, but not of most.

phasized the spiritual understanding of Scripture, and were less interested in the Bible's historical details of the life of Jesus, emphasized the divine nature of Christ. Their opponents charged that Alexandrians neglected Jesus' humanity, and called them "monophysites" (one-nature thinkers), meaning that they seemed to acknowledge only the divine nature of Jesus. That charge was probably true of some extreme Alexandrians, but not of most. - Antiochenes, who emphasized the Bible's historical details of the life of Jesus and the pastoral implications of his teaching, emphasized the human nature of Christ. Their opponents charged that they were inclined to attribute some characteristics of Christ to his humanity and others to his divinity in a way that divided Christ. Antiochenes could tend towards the so-called Nestorian position (named for a theologian called Nestorius), that not just two natures but two persons were comprehended in Jesus Christ.

Alexandrian and Antiochene approaches to Scripture and understandings of Christ are both considered orthodox as long as neither of them tries to exclude the other. Pretty much every Christian tends to be one or the other, usually more or less reflexively and without being aware of it.

Some parties to the controversy

The Apollinarians in the 350s thought that the way to relate the divine and human natures together of Jesus Christ was to say that in Christ the Logos took the place of the human mind. My Church and Society in Documents text reproduces Gregory of Nazianzus' answer to this: Gregory said that if, as the Apollinarians said, Jesus hadn't had a human mind, his humanity would have been maimed and incomplete. But Christ's redemption of humanity depended on his assumption of human nature at the Incarnation. What Christ didn't assume, he couldn't have healed. (Note: "Apollinarians" are named after the heretic Apollinaris. The word isn't an offshoot of "Arians.")

The Nestorians thought that the way to connect the two natures was to ascribe some characteristics of Christ to the human nature, others to the divine Son of God. Most provocatively, Nestorius himself, an archbishop of Canterbury, declared that Jesus' mother Mary wasn't "the mother of God" because she was only the mother of the human part of Jesus. Nestorianism appeared to its opponents to give the Incarnate Lord a multiple personality.

The Eutycheans, named after Eutyches, the abbot of a monastery in Constantinople who was outraged by Nestorius' theology, thought that the way to connect the two natures was to understand the human as being submerged into the divine at the Incarnation. That seemed to suggest to their critics the implication that when Christ wept or suffered or otherwise appeared human, he wasn't expressing his humanity; he was just playacting.

Steps to Chalcedon

Since Christianity by the fifth century had become the Imperial religion, theological debates that divided the Church also divided the Empire, and were a political threat. So the Emperor called an ecumenical council in 431 at Ephesus, marked by a bit of theological reflection and a whole lot of political manuevering. It condemned Nestorianism.

Quarreling continued, and the Emperor called another council at Ephesus in 449 which fully accepted the mainline Alexandrian position. Eastern Orthodoxy and western Christianity have never accepted this council as a legitimate ecumenical council.

In 450, therefore, it looked as if the Alexandrians were on the verge of decisively vanquishing the Antiochenes. The Emperor and most of the court were Alexandrians. The most powerful bishop was the patriarch of Alexandria. Alexandrian bishops were being appointed to dioceses that became vacant. Antiochenes were being hounded.

There then occurred one of those apparently random events that change the course of church history. The Emperor, Theodosius II, seen here on one of his coins, fell from his horse and died. His sister Pulcheria (shown on the coin to the right), who was sympathetic to the Anticoochenes, became Empress. Since she was the first woman to ascend the Roman throne, her position was tenuous, so she married. In 451 she and her husband convened a council at Chalcedon, which was near enough to Constantinople to be safely under their control. It defined as orthodox the position that Jesus Christ has two natures, human and divine, in one person, without confusion and without separation. Note the negative character of the definition: without confusion and without separation. The Chalecedonian definition didn't define how the two natures of Christ were related but how they were not. Take the link to read the Chalcedonian definition.

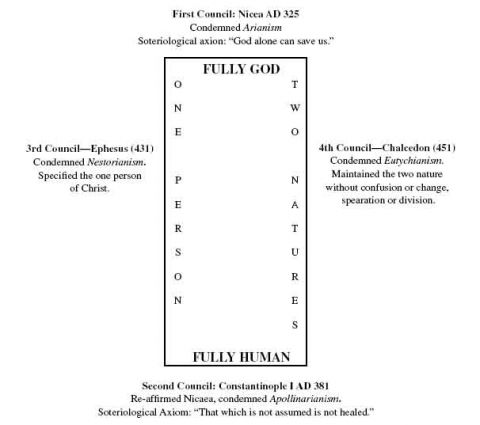

The First Four Councils

For western Christians, the first four ecumenical councils – Nicea 325, Constantinople 380, Ephesus 430, Nicea 451 – are the most important ones, since they establish the foundational doctrine of the Trinity and of the natures and person of Jesus Christ. For mainline Protestants, they are often serve as the only recognized ecumenical councils.

Richard Hooker, a sixteenth-century Anglican theologian, summed up the teaching of these four councils in the following way:

There are but four things which concur to make complete the whole state of our Lord Jesus Christ: his Deity, his manhood, the conjunction of both, and the distinction of the one from the other being joined in one. Four principal heresies there are which have in those things withstood the truth:

➤ Arians by bending themselves against the Deity of Christ;

➤ Apollinarians by maiming and misinterpreting that which belongeth to his human nature;

➤ Nestorians by rending Christ asunder, and dividing him into two persons;

➤ the followers of Eutyches by confounding in his person, those natures which they should distinguish.

Against these there have been four most famous ancient general councils:

➤ the council of Nicea to define against Arians,

➤ against Apollinarians the council of Constantinople,

➤ the council of Ephesus against Nestorians,

➤ against Eutychians the Chalcedon council.

In four words, alethos, teleios, adiairetos, asungchutos, truly, perfectly, indivisibly, distinctly; the first applied to his being God, and the second to his being Man, the third to his being of both One, and the fourth to his still continuing in that one Both:

we may fully by way of abridgment comprise whatsoever antiquity hath at large handled either in declaration of Christian belief, or in refutation of the foresaid heresies. Within the compass of which four heads, I may truly affirm, that all heresies which touch but the person of Jesus Christ, whether they have risen in these later days, or in any age heretofore, may be with great facility brought to confine themselves.

The following graphic summarizes this. I've taken this from Fred Sanders and Klaus Issler, eds., Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective: An Introductory Christology (Nashville, 2007), p. 23.

Why does this matter?

Because when we love someone, we want to know and understand them.

Because in order to worship in truth, we need to seek the truth. In particular, our sacramental theology depends on our Christology.

Because a sound Christology is the basis of an entire theology, including pastoral theology and practical theology.

Because Scripture calls us to give a reason for the hope that is within us. From a theological point of view, confidence in our redemption depends on a true understanding of Christ.

Because if Christ wants the Church to be one, then we need to know why it isn't one, so that we can help heal our divisions.

Because theological error can do damage. (A work on this theme is C. FitzSimons Allison, The Cruelty of Heresy, which argues that distortions of truth damage our humanity.)