The Age of Justinian and Theodora

The Emperor Justinian , who ruled from 527 to 565, is the most important figure of

this period, and some believe him

, who ruled from 527 to 565, is the most important figure of

this period, and some believe him to be the most important Roman emperor of all, though he wasn't exactly the most successful. A Slavonic peasant, he was adopted by his uncle, an emperor. He was raised in Constantinople and extremely well educated. He went to work as a government administrator, became co-emperor with his uncle, and on his uncle's death became sole emperor. However, some sources declare that it was his wife, Theodora, who really functioned as emperor. In any event, they ruled together until her death in 548. She was one of the most powerful women in the ancient world. All agree that she was beautiful and witty. Some early sources, however, speak unfavourably of her reputation and morals, which perhaps should be seen as typical smears of successful women in patriarchal societies.

to be the most important Roman emperor of all, though he wasn't exactly the most successful. A Slavonic peasant, he was adopted by his uncle, an emperor. He was raised in Constantinople and extremely well educated. He went to work as a government administrator, became co-emperor with his uncle, and on his uncle's death became sole emperor. However, some sources declare that it was his wife, Theodora, who really functioned as emperor. In any event, they ruled together until her death in 548. She was one of the most powerful women in the ancient world. All agree that she was beautiful and witty. Some early sources, however, speak unfavourably of her reputation and morals, which perhaps should be seen as typical smears of successful women in patriarchal societies.

Their achievements

They issued a new code of Roman law, the Corpus Iuris Civilis, published in three parts between 529 and 534. The code gave huge authority to the emperor. It removed religious rights from everyone who wasn't an orthodox Christian. Something that looks progressive: the laws gave women property rights and rights in divorce cases. Justinian's legislation was written in Greek: few in the west read Greek, a sign that the western Empire is becoming more marginalized.

In 532 the Nika ("Conquer") Revolt, which was a rebellion of two factions ("blues" and "greens") of horse-chariot teams and soldiers, threatened his government. His army put it down brutally, slaughtering many thousands. This was an important moment in the development of Byzantine absolutism and brutality.

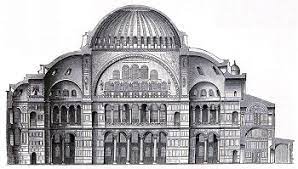

Since in the rebellion the great cathedral Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was burned, he re-built it (it's still there in Istanbul).

He also built numerous other public buildings, fortifications, and churches, in a style that came to represent Byzantine architecture. The most important public building, the Hippodrome, was an arena that could seat 40,000 people.

He suppressed the Platonic academy and pagan forms of education. He used the power of the state against Jews, pagans, Christian heretics, and philosophers.

He battled the Persians on the eastern border of the Empire in three wars.

He sought to re-conquer the western empire from the Barbarians, at great cost financially and in other ways (540 – 554). He made Ravenna, Italy, his western capital (exarchate). (Here is his church of San Vitale in Ravenna.) In order to direct military energies in Italy, he had to buy peace from the Persians by paying them huge amounts of tribute in gold.

He sought to re-conquer the western empire from the Barbarians, at great cost financially and in other ways (540 – 554). He made Ravenna, Italy, his western capital (exarchate). (Here is his church of San Vitale in Ravenna.) In order to direct military energies in Italy, he had to buy peace from the Persians by paying them huge amounts of tribute in gold.

Over-extended militarily, he could do little to prevent waves of barbarians Slavs and Bulgars) from taking over the Balkans. But he had more success in campaigns against the Goths and Vandals.

Consequences for his successors

After Justinian's death, the Empire didn't have the energy to maintain its hold on the west. New barbarian conquerors claimed the western territories of the Roman Empire.

Persia, recognizing the Empire's weakness, waged new wars.

Justinian's conquests over the Goths and Vandals left the way open for the Franks to become the dominant barbarian nation in the west.

In general, Justinian's financial and military over-extension left the way open for Islam to take over huge amounts of Byzantine territory in the following century.

There was a reaction against imperial absolutism, and a loss of prestige for the imperial government.

The aftermath of Chalcedon

The bitter debates of Chalcedon, so far from ending the Christological controversies, began a crisis which lasted into the Muslim period.

Non-Chalcedonians, of the variety that the Orthodox called Monophysites, were widely distributed in Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. These were wealthy areas, and strategic to the imperial defence. In these areas, Chalcedonian orthodoxy seemed to require the protection and support of Constantinople and was sometimes called the "Imperial" religion. (A term derived from Syriac for "Imperial" was "Melchite" or "Melkite"; through the centuries, several Byzantine rite Catholic Churches have been called Melkite.) In these non-Greek areas, the Byzantines were seen as the party of oppression; the non-Chalcedonians were more distinguished for piety and learning. The patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem were often in schism from Constantinople.

The emperor Zeno issued an edict of union (the "Henoticon") in 482 in a vain attempt to bring Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians together. (The document in translation can be found in Evagrius' ecclesiastical history, Book III, chapter 14.) It re-stated christological doctrine in a fuzzy way that pleased neither party. It was condemned by the Pope, and caused a schism between East and West from 484 to 519, when a new emperor simply ignored it.

In the 510s, 520s and 530s, the non-Chalcedonian opposition was led by Severus of Antioch. But there were many divisions among the non-Chalcedonians, which weakened their effectiveness. Meanwhile, the Persian churches were committed to the non-Chalcedonian theology which the Byzantines called Nestorianism, though the actual theological differences were seldom easy to discern.

The emperor Justinian (ruled 527 – 565) attempted to solve the christological problem partly by police repression (arrests, torture, mock trials, exiles, executions) and partly by theological intrigue. Since both Chalcedonians and so-called Monophysites agreed on opposing so-called Nestorians, Justinian drew up an edict condemning three pre-Chalcedonian texts ("the Three Chapters") as Nestorian, hoping that most people would see this as a way to reconciliation. (The enemy of my enemy is my friend!) He called an Ecumenical Council to meet in 553 at Constantinople, which dutifully condemned the Three Chapters. Formally condemning long-dead Christians as heretics was a new thing. The Pope, who did not attend, and who could not read the texts because they were in Greek, was bullied and beaten until he assented. Other western leaders rejected the Council, leading to schisms. In the long-term, this violent controversy helped alienate east from west, accustomed the east to theologically authoritarian emperors, and chilled theological dissent and discussion. It did not solve the Monophysite controversy.

An extreme Monophysite bishop from Syria named Jacob Baradeus, worried about Justinian's policies, began in 553 to travel around in disguise secretly ordaining bishops. The Syriac Orthodox Church still today is informally called "Jacobite" in memory of Jacob Baradaeus.

In the 620s the emperor Heraclius and the patriarch of Constantinople, Sergius, thought they hit on a new way of affirming Chalcedon while reconciling monophysites: this was "Monothelitism," the theory that Christ had one will, combining the divine and human ("theandric"). Many Egyptian monophysites accepted the definition and united with Constantinople. In 638 Heraclius and Sergius wrote a doctrinal exposition called the Ekthesis of Heraclius, which affirmed a single will in Christ. Protests followed from many Orthodox bishops and some synods. The Pope, Martin I, objected, and on orders of the new emperor, Constans II, he wa kidnapped, tried, and condemned to death. Maximus, one of the greatest of Eastern theologians, also objected, and he was kidnapped and tortured, dying of his injuries. The tide turned with the appointment of a new emperor. Monothelitism was condemned at the Sixth Ecumenical Council at Constantinople in 680.

In the 620s the emperor Heraclius and the patriarch of Constantinople, Sergius, thought they hit on a new way of affirming Chalcedon while reconciling monophysites: this was "Monothelitism," the theory that Christ had one will, combining the divine and human ("theandric"). Many Egyptian monophysites accepted the definition and united with Constantinople. In 638 Heraclius and Sergius wrote a doctrinal exposition called the Ekthesis of Heraclius, which affirmed a single will in Christ. Protests followed from many Orthodox bishops and some synods. The Pope, Martin I, objected, and on orders of the new emperor, Constans II, he wa kidnapped, tried, and condemned to death. Maximus, one of the greatest of Eastern theologians, also objected, and he was kidnapped and tortured, dying of his injuries. The tide turned with the appointment of a new emperor. Monothelitism was condemned at the Sixth Ecumenical Council at Constantinople in 680.

Hagia Sophia, the cathedral for Constantinople, one of the "seven wonders of the medieval world,"pictured here, was the site of the Second Council of Constantinople in 553. (The Third Councli of Constantinople, 680, met in the Imperial palace.)

Maximus the Confessor

Maximus (580 – 662) is called "the confessor" because his witness to Orthodoxy, as described immediately above, led to his persecution, torture, and death. He's also known as Maximus the Theologian, and is sometimes considered the greatest of Byzantine theologians, and one with particular ecumenical importance. He understood himself to have been inspired by Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus, and like them, he was evidently influenced by Neo-Platonism. A primary theme in his work is that the material order is essential to God's plan for bringing the universe to perfection, and that the full humanity of Christ is essential to the redemption of the world. Christ's full humanity includes suffering and temptation: indeed, we can't avoid suffering as our bodies come more and more to participate in the divine nature. And the perfection of Christ's full humanity overcomes and reconciles all human divisions, including sexual differentiation, in a way that begins to be available to us in our baptism. With baptism, the Christian life is centred on love, both God's love for us and our love in return for God and neighbour, all always grounded in the supreme act of love, Christ's Incarnation.