Francia

The Franks, a Germanic people, emerge into the historical record in the third century CE, and they become a major western period under Clovis (d. 511). He made his capital in Paris. In 508, influenced by his wife, Clovis was baptized a Catholic Christian, a significant event since most Germanic Christians were Arians. As Francia grew in political clout over the next many generations, a resulting trend was the growing religious unification of European peoples within a Catholic Christianity centred on the papacy.

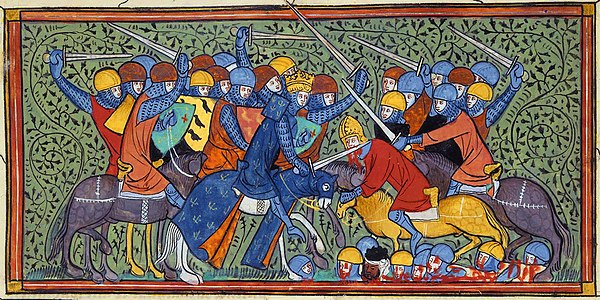

The Carolingian dynasty of Francia emerges with Charles Martel (d. 741). He himself was never king of the Franks, but was the power behind the throne, in the capacity of a major administrative official called "the mayor of the palace." (The word "Carolingian" derives from Charles Martel's Latin name, Carolus.) In 732 Charles Martel gained particular prestige by defeating the Muslim armies at Poitiers and Tours. His son Pepin the Short became the first king of the Carolingian dynasty in 751, through a bloodless coup. Pepin's son Charles, called "the Great" (Carolus Magnus, or Charlemagne), became king in 768, and emperor on Christmas day, 800.

Charles Martel's army confronting the Muslim armies from the Umayyad Caliphate (in what's now Spain) at the Battle of Tours-Poitiers, 732.

The rise of the papacy

Before 650

We've already seen a number of reasons for the importance of the diocese of Rome, including the following:

- The city was very important as the long-time capital of the Empire.

- It was the only western diocese with a clear apostolic connection (Paul, certainly; Peter, probably). It claimed the relics of Peter.

- In the legislation of Justinian, it emerged as one of the five holy sees of the Christian Pentarchy, and the only one in the west. (The others were Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, and Jerusalem.) In the theory of the day,, they jointly constituted the government of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.

- Through the centuries, Rome was often consulted by other western dioceses on canonical and theological issues, and thus developed a certain moral authority.

- It was always on the winning side of the various Eastern christological controversies, and thus acquired a reputation for orthodoxy, consistency, and theological stability.

- As civil government in the Italian peninsula collapsed in face of Germanic invasions and conquests, the bishop of Rome had increasingly assumed many temporal responsibilities.

- With Gregory the Great, the papacy had assumed ever larger authority for missionary work, ecclesiastical appointments, and church discipline in the west.

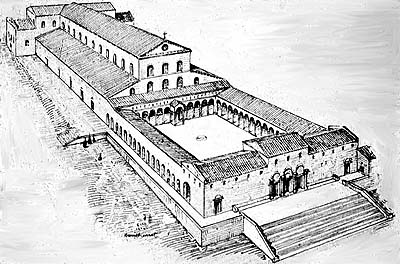

Pictured is "Old St. Peter's," the basilica which Constantine had built on the site of the aedicula commemorating the martyrdom of St. Peter. It was torn down in the sixteenth century to make room for the present St. Peter's.

After 650

From the seventh to the ninth centuries further circumstances consolidated the authority of the medieval papacy:

- Constantinople was no longer able to sustain its power over Italy. Even with its "Imperial Exarchate" in Ravenna, on the Italian peninsula, its capacity to enforce its legal jurisdiction in the west was diminishing, and then in 751 Ravenna fell to the Lombards. Byzantine authority in Italy was eradicated.

- In 756 Pepin, king of the Franks, took from the Lombards the lands that the Lombards had taken from the Byzantines, and gave them to the Pope. This was a significant amount of territory grouped along a diagonal line across the Italian peninsula from Ravenna to Rome. This gift is called the Donation of Pepin. It made the pope a substantial temporal ruler. The Donation of Pepin is sometimes considered the origin of the Papal States, a large piece of Italy under the sovereign jurisdiction of the Pope. (The Papal States would grow to a size of over 40,000 square kilometres, and would finally be formally surrendered to Italy in 1929, leaving the Pope with 110 acres, constituting the independent state of Vatican City.)

- Most Arianism was eliminated. One of the last holdouts, the Lombards, converted to Catholicism in 698, after long persistent missionary work. Rome no longer had a rival set of bishops to distract its energies.

- Pilgrimages to Rome developed. Its distinctive liturgy, ceremonial, and church decorations made it an attractive destination. Its growing reputation as a holy site strengthened its moral and spiritual authority.

- Prestige had a way of snowballing. As more abbots came to the pope for recognition, and as more bishops came to the pope for ordination, and as more missionaries came to the pope for commissioning, ever more abbots, bishops, and missionaries looked to Rome as a source of ecclesiastical authority.

- And then on Christmas day in the year 800 the pope crowned Charlemagne emperor. That announced that the pope could make emperors.

At right: Charlemagne crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III. Public domain.

Charlemagne

Charlemagne inherited the crown in 768. He conquered Saxony and Lombardy, and by the time he was through conquering, his territory extended over most of western Europe, except al-Andalus (which was controlled by the Emirate of Cordóba) and southern Italy (which was retained by the Lombards). In 800 the pope crowned Charlemagne emperor, much to the surprise of the emperor in Constantinople, who thought that he was the emperor.

The centre of Charlemagne's empire was Aachen, a town located in what is today in western Germany on the border with Belgium and the Netherlands. (In English it's called by its French name, Aix-la-Chapelle.) The chapel in his palace is pictured here; it still stands, and serves as the cathedral for Aachen diocese.

Charlemagne and European unity

In recent decades Charlemagne's empire has been seen as embodying a vision for European unity. At least a dozen modern countries are geographically located in what was once Charlemagne's empire, and the example of a single political and administrative authority in charge of peoples of different languages and cultures has inspired some of the architects of the European Union and the Schengen Area. A high-rise building in Brussels that houses European Union offices is called the Charlemagne Building, and the best-known prize given to someone who has made a contribution to European unity is called the International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen. All empires, however, seem to generate restlessness, and the European Union, despite having no one of Charlemagne's clout anywhere in sight, is seen by some as being managed by people with imperial aspirations.

The Carolingian Renaissance

Charlemagne's period is characterized by important developments in government administration and a renaissance in scholarship. The star of Carolingian scholarship was no doubt Alcuin (c. 735 – 804), whom Charlemagne brought from York in what is now the north of England (then Northumbria) to run the palace school. He also wrote theological works, and promoted the copying of manuscripts. Another figure of the Carolingian renaissance was Theodulf (d. 821), bishop of Orléans, who probably wrote the most important western statement on iconoclasm, the Libri carolini. (He opposed iconoclasm.) He's best known to us today as the author of the hymn "All glory, laud, and honour". Other Carolingian developments in church affairs include:

- the reform and standardization of the liturgy,

- a reform and standardization of the rules of monastic life,

- a revision of canon law,

- missionary activity,

- a new system of legible and beautiful writing, called Carolingian minuscule, and scriptoria for the copying of manuscripts of Christian and classical learning,

- intentional systems for the education of clergy,

- the learned discussion of theological issues,

- a blossoming of sacred art, and

- the Synod of Frankfurt.

Aachen chapel, shown here, was part of Charlemagne's palace. The palace is gone, but the chapel has been preserved as part of the Aachen cathedral.

The Synod of Frankfurt (794)

The Synod of Frankfurt was a significant event in western church history for several reasons: it was convened by Charlemagne, not the Pope; Charlemagne was acclaimed as a "priest" (sacerdos by virtue of his being anointed by God; the council was attended by church leaders from across the kingdom; preparations were thorough and substantial; the conclusions of the Synod were important.

Among the considerable documentation produced in advance for the Synod, including agendas and treatises, the most notable was the Libri Carolini, which included theses on the devotional use of representational art. These were evidently intended as a response to the Second Council of Nicea of 787, with its high view of icons: or, to be precise, they were a response to the reports which they had received about Nicea II, which weren't quite accurate. Participants at the Synod of Frankfurt felt no obligation to agree with Nicea II. The Synod thus gives evidence that western Christianity now understood itself to be independent of the authority of the Byzantine Empire and the Eastern hierarchy. To put it otherwise, Eastern-dominated ecumenical councils could no longer speak for the universal Church.

Among its conclusions, the Synod of Frankfurt:

- Passed 56 canons;

- Rejected Nicea II and the "worship" of images (actually, Nicea 2 hadn't affirmed image "worship");

- Rejected the Spanish heresy of "adoptionism".

- Proclaimed the filioque clause of the Nicene Creed to be proper teaching.

- Approved Charlemagne's monetary reform.

- Condemned belief in witchcraft as superstitious, and prohibited the persecution of alleged witches.

- Affirmed the legitimacy of prayer in the vernacular languages.

The Treaty of Verdun (843)

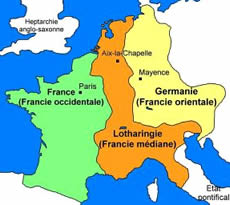

Charlemagne was succeeded by his son Louis "the Pious". On Louis' death, his three sons fought for control. Their wars were settled by the Treaty of Verdun, which divided Charlemagne's kingdom three ways. (The text itself hasn't survived.) Linguistic differences probably determined the boundaries; in west Francia people spoke Romance languages (descended from Latin); in east Francia they spoke Germanic languages. But something like this division became permanent. This was thus the beginning of our modern European map.

Here is a map of the area covered by the Treaty of Verdun. You can see that the western section looks a lot like the territory of modern France, the middle section a lot like the territory of the Low Countries / western Switzerland / northern Italy, and the eastern part a lot like the territory of modern Germany. In other words, this is the point at which the political map of modern Europe begins to take shape.