Early Christian diversity

Evidence for Christian diversity appears already in the New Testament. This incorporates the writings of various Christian communities each telling the story of Jesus, and interpreting the importance of Jesus, in distinct ways.

Wider diversity can be found in early Christian writings which were not admitted to the New Testament. Some of these non-canonical Christian writings seem sufficiently catholic to be considered sub-apostolic (that is, written by orthodox

Christians in the age after  that of the apostles); often these are collectively called "the apostolic fathers". But there are still other writings by people who considered themselves followers of Christ but which seem to us rather wild. The most notable of these are called "Gnostic writings".

that of the apostles); often these are collectively called "the apostolic fathers". But there are still other writings by people who considered themselves followers of Christ but which seem to us rather wild. The most notable of these are called "Gnostic writings".

The term "early Church" is often used as a normative term. It's "the Church" if it's in recognizable continuity with the Christian faith that we recognize as legitimate today; otherwise, it's something else. And, in this view, there's no need to study it if it's something else. And, true enough, in this course, which has a lot to cover, we won't spend a lot of time with the groups that turned out to have been outliers. But we should pause long enough to note that the singular "early Church"may misleadingly imply that the early Christian movement was monolithic. There was no central Church authority in the centuries that it was illegal, and different groups were free to practice Christianity in different ways that were creative and locally meaningful. What became Catholic Christianity took shape in the arguments and rivalries of a variety of groups, and, even then, it wasn't homogeneous.

Many historians speak of their study of "early Christianity" rather than "early Church history" because they want to take account of all who considered themselves Christian, whether or not they belonged to a recognized church community that has had a subsequent continuous institutional tradition.

Gnosticism

González introduces you to Gnosticism in Chapter 8. We study this in our course as a set of Christian heresies which induced mainstream Christians to clarify their doctrine and tighten up their organizational structures. In a short introductory course, we don't probe its diversities and subtleties. But others do study Gnosticism as a topic in its own right, not just a foil to Christianity. If nothing else, it's evidence that religious views connected with the figure of Jesus were extremely varied in the early centuries, and the lines of demarcation took a while to draw. And some modern students and scholars of Gnosticism  are quite attracted to it in its own right, and find it more appealing than orthodox Christianity.

are quite attracted to it in its own right, and find it more appealing than orthodox Christianity.

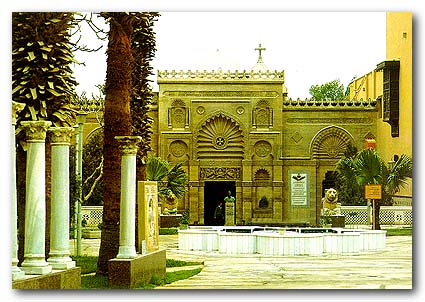

A large library of Gnostic Christian writings was discovered in 1945 in Egypt, in a cave near a place called Nag Hammadi. It appears that someone in the fourth century or thereabouts hid these manuscripts there, for reasons unknown. After these manuscripts were discovered, the Coptic Museum in Cairo (shown here) and the Egyptian government strived for many years to keep them under their own control. In the 1960s the United Nations, through its agency UNESCO, began pressuring for their release. Finally in the mid-1970s these writings were published and translated into modern languages.

Before the mid-1970s, very few Gnostic writings were known. When I took my own first Church history class, almost all we knew about Gnosticism came the from the early orthodox Christians who fought it. Of course, they were biased witnesses.

The Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas, the subject of one of our readings, was found among the Nag Hammadi documents. Perhaps largely for this reason, the document is usually considered to be a Gnostic writing, although it's rather different from other Gnostic writings. If you read the other Nag Hammadi writings, you'll find them generally pretty difficult to read, full of cosmic speculations in unfamiliar language. The Gospel of Thomas, by contrast, is quite accessible. It's made up almost entirely of sayings of Jesus, but about half of them are sayings of Jesus which will be quite unfamiliar to you. (Have you taken "Introduction to New Testament;"? If you have, you'll recognize the form of the Gospel of Thomas as what the "Q source", the hypothetical ancient anthology of sayings of Jesus, would look like, if we still had it.) So the Gospel of Thomas may well have different historical origins from the other Nag Hammadi documents.

What is the "tendency" or ideological predilection of the Gospel of Thomas? If you read the document closely, a few alternative hypotheses may well commend themselves to your mind. A Wikipedia entry may help you think about this (if you don't let it intimidate your creative imagination!).