Almost all the material below is courtesy of and adapted from Robert Holmstedt, Department of Near and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Toronto.

What is the canon?

"Canon" is a Greek word (κανων) that comes from the Hebrew word

קָנֶה, which means "reed, measuring rod." Although the  denotation is a literal measuring rod, as in a school ruler or metrestick, it came to connote a “rule” or “standard” in a more abstract way. We also use this term in modern English when we refer to “canon law,” referring to regulations for church life. Scripture came to be seen as the rule against which to measure the Church's proclamation of the Gospel. Which gospels, letters, treatises, histories, etc., were authoritative? The history of the canon has to do partly with how the idea of canonicity developed, and partly with how Christians decided which books of Scripture to include in the canon.

denotation is a literal measuring rod, as in a school ruler or metrestick, it came to connote a “rule” or “standard” in a more abstract way. We also use this term in modern English when we refer to “canon law,” referring to regulations for church life. Scripture came to be seen as the rule against which to measure the Church's proclamation of the Gospel. Which gospels, letters, treatises, histories, etc., were authoritative? The history of the canon has to do partly with how the idea of canonicity developed, and partly with how Christians decided which books of Scripture to include in the canon.

The illustration shows an ancient Egyptian measuring rod. It's inferred from examples such as these that a cubit was 52 cm.

Which documents should be treated as authoritative was an issue of hot debate for the first few centuries of Christianity. If one fellow in the second century (Marcion, CE 100 – 160) had had his way, the Christian canon would have consisted of the Gospel of Luke and Paul's letters in edited form. No Old Testament, and no other New Testament writings, would have been admitted.

The result of these discussions was "the Bible". "Biblion" is a Greek word meaning simply “book.” This is an interesting designation, since “book” denotes a finished product. When we think of the Bible as a "book", we're looking back at it retrospectively in its finished form as a single, fixed entity. Historians of early Christianity, however, want to understand the events and processes that shaped this book we consider sacred. At many points there are some surprises. For instance, we think of the "Old Testament" as being established before the "New Testament," but for the earliest Christians the Old Testament was still “in-the-making.” That is, its Table of Contents, so to speak, wasn't yet fixed. And the New Testament, that specifically Christian addition to this body of sacred Jewish literature, wasn't conceived until decades after Christ’s death.

Athanasius' "Festal Letter" of A.D. 367 is the first to declare the canonicity of precisely our 27 books of the New Testament, in the order in which we have them. He was reporting what he took to be the norm already. Christian writers were working with widely agreed sacred texts long before that, although the authority of some books that were included was controversial, and some books that were excluded had their proponents. Indeed, different groupings within the Christian Church have different Bibles; for instance, Roman Catholic Bibles include some Old Testament books that Protestant Bibles don't.

Textual traditions of the Old Testament

We'll start by considering the textual traditions of what Christians call the Old Testament, and how they developed into a canon.

The Hebrew text

Almost all modern translations of the Hebrew Bible are based on a medieval text that is called “the Leningrad Codex,” since it was copied and is located in Leningrad/St. Petersburg, Russia. This is the oldest complete copy of the Hebrew Bible that remains intact, and dates from CE 1008/9 — a thousand years removed from the last possible stages of writing or editing for any of the books!

What is important to know about this Hebrew text of the OT is that it represents a very long tradition: while it's from CE 1008, it's connected to the earliest form of the OT by over a thousand years of tradition, copying, and preservation.

By BCE 200 the Hebrew texts were being translated into two other languages: Aramaic, which is quite similar to Hebrew, and Greek, which is quite different. The early translations were necessary because Aramaic displaced Hebrew after Jerusalem was destroyed in the 6th century BCE, and large numbers of Jews were taken into exile to Babylon, where, soon after, Aramaic became the official language of the empire. Then, in the 4th century BCE, when Alexander the Great dominated the region, Greek became the lingua franca (the common language), leaving Hebrew as a liturgical language that was likely understood by few Jews outside Judea. In this context, the Jewish community was in need of a way to access the Torah for study and worship. Where Aramaic was spoken, the Aramaic translations arose; where Greek was dominant, the Greek translations arose. This translation activity could have been a formal affair or it could have been much more informal, the product of many individuals over a period of time.

Greek "Septuagint"

What is especially important is that the Greek translation, which is commonly called the “Septuagint” and abbreviated "LXX," has it origins in the mid-3rd century BCE, among Egyptian Jewry, and at first almost certainly included only the Torah (the Five books of Moses, the first five books of the Christian Old Testament). Later, the rest of the Biblical books were translated, with varying degrees of literalness. A Greek OT (which also likely existed in multiple forms) appears to have been used by most of the NT writers, and became a significant factor in debates between early Christianity and Judaism. The Greek Bible, later including both the OT and NT, became the authoritative text for most of the Eastern European Christian church, reflected in various Orthodox groups today. Protestants use translations of the Hebrew OT, which includes fewer books than the Greek OT.

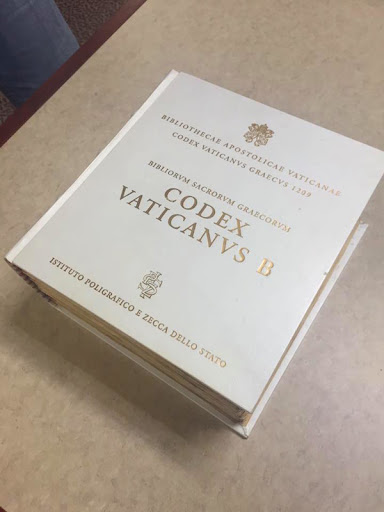

Our oldest existing copy of the Bible is a version of the Greek Bible from c. CE 360, which is stored at the Vatican and thus is called "Vaticanus."

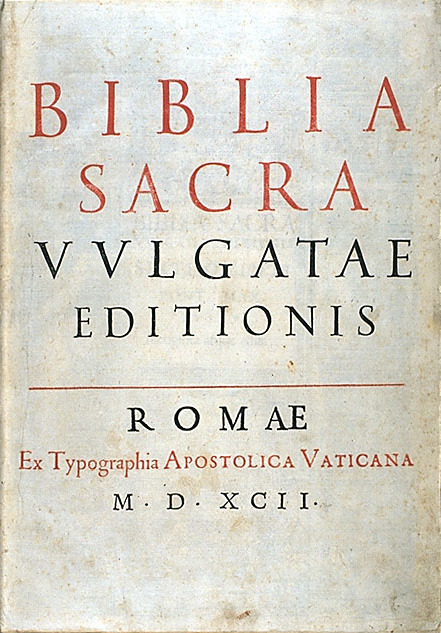

Latin "Vulgate"

After the Greek Bible, the next most important translation is the Latin Bible. The Latin Bible started as a variety of individual translations of biblical Books, most likely made by either Jews more probably Christians who lived in the western Mediterranean, within the smaller circle of Latin influence around Italy during the Roman period. Thus, the books of the Christian Bible (OT and NT) were all translated into Latin by the end of the second century within the emergent Christian church of the West, whose centre of gravity was Rome. However, there were a number of Latin texts, varying in their quality of translation. In CE 382 Pope Damasus commissioned the multilingual scholar Jerome (CE 346 – 420) to undertake an authoritative Latin translation for the Roman Church.

After the Greek Bible, the next most important translation is the Latin Bible. The Latin Bible started as a variety of individual translations of biblical Books, most likely made by either Jews more probably Christians who lived in the western Mediterranean, within the smaller circle of Latin influence around Italy during the Roman period. Thus, the books of the Christian Bible (OT and NT) were all translated into Latin by the end of the second century within the emergent Christian church of the West, whose centre of gravity was Rome. However, there were a number of Latin texts, varying in their quality of translation. In CE 382 Pope Damasus commissioned the multilingual scholar Jerome (CE 346 – 420) to undertake an authoritative Latin translation for the Roman Church.

Jerome’s first translation was based entirely on the Greek LXX, but his later revision used both the LXX and a Hebrew text. Because this new translation became the “common” text within the Western Church, it became known as the Vulgate (which means “common” in Latin). The Vulgate remained the authoritative version of the Bible for the Roman Catholic Church and was used in the Mass until Vatican II in the 1960s.

Syriac “Peshitta”

The final ancient translation that is worth mention is the “Peshitta,” which is in a language called Syriac, a form of Aramaic and thus closely related to Hebrew. It appears that Syriac translations of the OT go back to the first century CE and were likely Jewish in origin, since Syriac had become a major language to the north and east of Palestine. However, many of these communities were affected by the spread of Christianity and thus the texts of the Syriac Bible that we have include the NT. Again, like the Greek and Latin Bibles, the Syriac Bible is almost certainly the product of many translators from many different periods.

Summary

The reason for knowing about all these translations is that once the OT and then later the NT were translated into another language, those texts and the communities that used them often developed differences from other Christian communities that used a different language. The differences ranged from non-essential details of specific verses to major differences in the exact list of books contained in the Bible and in some cases issues of theology, such as the nature of the person and work of Jesus Christ.

The canon of the Old Testament

Why was a limit set for scripture (whether Jewish or Christian)? The primary motivation was broad coherence and unity. Simply put, if there is no standard, no norm, no rule, then “anything goes”! This doesn’t lend itself to any sort of common ground among those who want to share a faith. So, in order for something to be judged as valuable for the faith community, and thus as inspired, it’s only reasonable that something came to exist that became the standard, the ruler by which everything was measured. Hence, the canon.

Different canons

A significantly complicating factor in any discussion of canon is that different religious communities subscribe to different canons of the Bible. What do I mean? I mean that if you are Jewish, you subscribe to a different list of texts that you call the Bible than if you are Protestant Christian. If you are a Protestant Christian you subscribe to a different list than if you are a Catholic Christian, and Catholics subscribe to a slightly different list than Eastern Orthodox Christians. If we were to throw in the Samaritans, a small religious community related to Judaism, or even Muslims, we could discuss other canons of the Bible.

Jewish canon

All of these communities do, however, share some Biblical books in common. Let’s consider the various Christian canons by first starting small with the Jewish canon. The Jewish Bible comprises 24 books:

| Law (Torah) | Prophets (Nevi'im) | Writings (Ketuvim) |

| “In the beginning” | Joshua | Psalms |

| “Names” | Judges | Proverbs |

| “And he called” | Samuel | Job |

| “In the wilderness” | Kings | Song of Songs |

| “The words” | Isaiah | Ruth |

| Jeremiah | Lamentations | |

| Ezekiel | Ecclesiastes | |

| “Book of Twelve” (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi) | Esther | |

| Daniel | ||

| Ezra-Nehemiah | ||

| Chronicles |

Each of these books is named by the first word of the book. (This would be like referring to Melville’s Moby Dick as “Call me Ishmael.”) The division of the books into the three sections indicated above happened after ancient times. The first letters of each division title are used to form an acronym which is the most common Jewish designation for their Bible: the TaNaK.

When was this three-part list of 24 books recognized as the Jewish “Bible”? That’s a very difficult question to answer. First, it appears that the three divisions were well established by the early first century CE (cf. Philo, CE 25, On the Contemplative Life, “Laws, Oracles...of prophets, Psalms and other books”). But the firm list of 24 books seems to be a bit later, towards the end of the first century (cf. Josephus, CE 90, Against Apion, "22 books, 5 books of Moses, prophets, and remaining 4 books”). Finally, it is clear from both the Dead Sea Scrolls evidence and the Septuagint that some books were not considered “closed” or “finished” even though the “book” was listed as Scripture; for instance, the Septuagint includes a 151st psalm in the book of Psalms and the Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit a number of different psalms in their psalms scrolls, and the order of the psalms even differs.

Thus, for the Jews (and accordingly for the early Christians), the “canon” as a fixed entity did not yet exist; the first century CE witnessed a “canon-in-the-making." This does not mean, of course, that the Jewish and Jewish-Christian communities did not have “Scripture,” but that their Scripture was still an open-ended body of literature. And this only makes sense: the Christian movement felt free to add their own distinctive literature to the mix. And indeed, this was among the historical forces that caused the Jewish community to feel the need for an explicit list of Scripture, i.e., a canon.

Besides the Roman oppression and the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in CE 70, the Jewish community perceived another, perhaps greater menace on the horizon that demanded reflection on the nature of their Scripture: this menace was “the emerging Christian movement." Christians used the same Bible but preached that Jesus was God’s promised Messiah and that the Scriptures predicted him. Their use of the Septuagint proved to be so problematic for the Jewish community that in the second century a man named Aquila produced an ultra literal translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek — one that eliminated problem passages such as “the virgin will conceive” in Isa. 7:14 [which was being used as a proof-text for Jesus’ messiah-hood]” (Cosby, Chp. 5, p. 11).

Then, “with the loss of the temple and the need to define what was and was not authentically Jewish,” the Jewish leaders began to discuss what Jewish Scripture was and why those 24 books were considered sacred.

Jamnia

The Jewish rabbinic writings called the "Mishnah" (about CE 200) reports a rabbinic assembly at Jamnia, a coastal town in Palestine, in around CE 90. Rabbinic leaders are said to have discussed why certain books were considered inspired and authoritative. For example, two of the “disputed” books were Ecclesiastes/Qoheleth and Song of Songs. The question they reportedly pondered was why these two books “made the hands unclean” (i.e., were divinely inspired). The problem with Ecclesiastes/Qoheleth was that it exhibited hedonism and skepticism in  God (except for the conclusion), and it was self-contradictory (Qoh 7.3 and 2.2, 8.15 and 2.2). The obvious problem with Song of Songs was the overt eroticism and sexuality. The historicity of the council of Jamnia has been doubted. But it is

probably a good reflection of how the rabbis understood the process by which the canon came to be: the fact that the rabbis discussed why certain questionable books were sacred suggests that they did not “decide” the canon; they merely sought a rationale for the shape of the already existing canon. Thus, the Jewish canon was not “made” by any authority; rather, it developed organically from the community. Similarly, we will see that the Christian canon developed by such an “organic” process.

God (except for the conclusion), and it was self-contradictory (Qoh 7.3 and 2.2, 8.15 and 2.2). The obvious problem with Song of Songs was the overt eroticism and sexuality. The historicity of the council of Jamnia has been doubted. But it is

probably a good reflection of how the rabbis understood the process by which the canon came to be: the fact that the rabbis discussed why certain questionable books were sacred suggests that they did not “decide” the canon; they merely sought a rationale for the shape of the already existing canon. Thus, the Jewish canon was not “made” by any authority; rather, it developed organically from the community. Similarly, we will see that the Christian canon developed by such an “organic” process.

Vaticanus and the "extra books"

We've already noted the translations of the Jewish Bible into other languages by the first century CE. The Greek Bible, or Septuagint, first consisted only of the Torah, but by sometime in the late first century BCE or mid-first century CE it included all the books of the Hebrew Bible. What is fascinating is that the Greek Bible, followed by the early Latin Bible, also included non-biblical Jewish books as well as early Jewish-Christian books. The other writings were almost all in Greek, not Hebrew, but once Jewish sacred literature was not associated exclusively with a specific language, Hebrew, it was not a significant hurdle to include other insightful, perhaps “inspired” books. These "extra? books are called "the Apocrypha"; they were all Jewish, and all written in the period before Christianity. The Vaticanus LXX (="Septuagint") includes the Jewish Bible plus the Apocrypha:

| Additions to Esther | 1 Maccabees | 4 Maccabees | Ecclesiasticus |

| Judith | 2 Maccabees | Psalm 151 | Baruch |

| Tobit | 3 Maccabees | Wisdom of Solomon | Letter of Jeremiah |

| Additions to Daniel |

The addition of these books is typically understood as a reflection of the Christian setting in which the Greek Bible became used extensively, but based on the evidence of the Dead Sea Scrolls, it is almost certainly the case that some Jewish groups used these “extra” books (except for the NT) at an early period, that is, before the end of the first century CE. (It's possible that the growing animosity between Judaism and Christianity at the end of the first century pushed the Jewish community to consider only Hebrew language texts as Scripture and thus to exclude the “extra” books from the Jewish Canon, or Jewish Bible.)

By the way, “in one of those [ironic] twists of history, Protestant Bibles today rely on the decision by Pharisaic teachers for which books should be included in the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible. Yet the order of the books in Christian Bibles comes from the sequence adopted in the Septuagint” (Cosby, Chp. 5, p. 12). We can thank that renegade of the Reformation, Martin Luther, who studied Hebrew and was aware of the canonical differences, for reverting back to the smaller Jewish Canon for the Protestant OT.

When Jerome translated the Bible into Latin for the official “Vulgate” version of the Roman Church, he made it clear in his preface that he considered the “extra” books to be of lesser status. “He distinguished between Scripture and what he called Apocrypha, using his prefaces to books to explain which were apocryphal. Those who made copies of Jerome’s translation were often careless about including his prefaces, however, so the distinctions he made were often lost. Jerome was a very influential thinker, and many Christians adopted his view on the canon of the Old Testament. Many others did not. Augustine (CE 354 – 430), for example, was a strong advocate for the larger Old Testament canon of 44 books (On Christian Doctrine 2. 8.13). On a practical level, therefore, when different Christians spoke of the Scriptures, they often did not mean exactly the same thing. The core books were the same, but there were arguments about disputed books. This remains true even today.” (Cosby, Chp. 5, p. 12).

The New Testament books (focusing on the Gospels)

What is a Gospel?

The first thing that will helpful for us in our study of the Gospels is to know what the word “gospel" means. The Modern English word “gospel” is actually the compounding of two separate Old English words, go:d ‘good’ and spel ‘tale’. Thus, the English word, at its core, simply means “good tale” or “good story”. This English word was a translation of the Latin word evangelium, which in turn was derived from the Greek word euangelion, which means "good news." But “good news” is not a literary genre; it indicates that the early Christians believed Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection to be a positive message that needed to be announced. But besides a basic judgment regarding the nature of the content, this term tells us very little about the content itself or the raison d'être and intended audience of these books.

It is now largely acknowledged in NT studies that the Gospels fit best into the category of ancient “biography”. But, it is important to distinguish this from modern biography. Modern biographers typically research their subjects like any historian of any topic does, and the research often includes extensive interviews. Furthermore, many biographies cover the whole span of a person’s life, typically starting with childhood. Some of this is true of biographies from the Greco-Roman world, but not all. In particular, Greco-Roman biographies were not the comprehensive report of facts about a person’s life hat modern biographies purport to be. Consider one of the most famous ancient biographers, and his methods: Plutarch, a Roman who created biographies for over fifty famous Greeks and Romans. His introduction to his "Life of Alexander the Great" has become famous:

In writing for this book the [life] of Alexander the king . . . I have before me such an abundance of materials that I shall make no other preface but to beg my readers not to complain of me if I do not relate all [his] celebrated exploits or even any one in full detail, but in most instances abridge the story. I am writing not histories but lives, and a man’s most conspicuous achievements do not always reveal best his strengths or weakness. Often a trifling incident, a word or a jest, shows more of his character than the battles where he slays thousands, his grandest mustering of armies, and his sieges of cities. Therefore as portrait painters work to get their likenesses from the face and the look of the eyes, in which the character appears, and pay little attention to other parts of the body, so I must be allowed to dwell especially on things that express the souls of these men, and through them portray their lives, leaving it to others to describe their mighty deeds and battles.

What we need to notice here: selective use of information; lives not histories, character portrait.

Similarly, the Gospels were not intended to be history writings, strictly speaking, although they include a lot of historical material. Rather, the NT biographies of Jesus were written to celebrate his character or accomplishments, but more so to make significant statements about God, Jesus’ relationship to God, and what Jesus’ ministry means for humanity, and to convince people that these things should be believed. And each Gospel was tailored to the backgrounds and needs of its primary intended audience.

That isn't to say that they don't display many points of agreement and a general consistency on the main issues of Jesus’ life, for they do:

- Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist;

- He was a Galilean who preached the kingdom of God (i.e., a new age);

- He performed miracles and healings;

- He called his disciples and spoke of there being twelve;

- He was crucified and was raised from the dead, according to a narrative in which he entered Jerusalem during the Passover celebration; he engaged in a controversy about the Temple; he was crucified outside Jerusalem by the authority of Pontius Pilate; his disciples witnessed his resurrected appearances.

And yet, the Gospels don’t always agree with each other.

Let me illustrate this biographical and audience-oriented perspective on the Gospels.

Luke and Jesus’ Origin

Consider for a moment an aspect of the birth narrative of Jesus as it is presented in Matthew and Luke. The question is: where did Jesus’ parents come from? The traditional Christmas story repeated at pageants basically follows the narrative that the Gospel of Luke provides. In particular, Luke identifies Nazareth as the hometown for Joseph and Mary (Luke 1:26-27). It was only because of a census held in one’s ancestral village that they wound up in Bethlehem (Luke 2:4). After Jesus’ birth, the family returned to Nazareth, and there Jesus spent his youth.

Matthew and Jesus’ Origin

In contrast, Matthew’s narrative provides no explanation as to what Joseph and Mary were doing in Bethlehem; that’s simply where the story of Jesus’ birth unfolds. In fact, the first time Matthew says anything about where Jesus was born is in his story of the arrival of the Magi, where Bethlehem is mentioned rather casually:

In the time of King Herod, after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem.

Moreover, when Joseph and Mary returned from Egypt after having fled Herod’s wrath, they apparently intended to return to Judea until they received discouraging news (2:21ff.):

Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother, and went to the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was ruling over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there. And after being warned in a dream, he went away to the district of Galilee. There he made his home in a town called Nazareth.

Notice that the words “he made his home in a town called Nazareth” give the impression this is the first time Joseph had lived in Nazareth. And the narrative gives the impression that he wouldn’t have wound up there if it hadn’t been for the continuing threat: he would have returned to Judea, which is peculiar if, as Luke reports, Joseph traveled to Bethlehem simply to fulfill the requirements of a census. Unlike Matthew, Luke makes nothing of Nazareth as Jesus’ hometown or that of his parents. However, he uses the story of the compulsory trip to Bethlehem to show that Jesus’ family roots run all the way back to David. That’s why the angel announces to the shepherds, “To you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord.” The “city of David” is a direct reference to Bethlehem.

The point

My point in this is not to say, “Look, we caught Matthew and Luke in disagreement about geography,” but to highlight for you the nature of the the Gospels: much like the history-writing we saw in the Hebrew Bible, the larger “truths” that each author was communicating sometimes overrode the bare facts. The differences in the ways Matthew and Luke handle geography don’t, then, have to do with “getting the facts straight”; that’s not their concern. Rather, they construct the geography so as to make points about who Jesus is.

What does this mean? First, it means that we need to read each Gospel separately, paying attention to its flow, and trying to discern its distinctive message of Christ.

So, how did the four Christian communities represented by the Gospels differ? A brief look at the four gospels will help us get an idea of how diverse early Christianity was (and if we had time to look at the NT Letters, we would see the same range of diversity, among the letters themselves, or between the authors of the letters and some of the “opponents” that they write against.

Overview of the Four Gospels

Mark

We can tell that Mark's audience was not very Jewish (probably overwhelmingly Gentiles) due to a number of “explanations” that Mark gives about Jewish practices. Furthermore, they were Greek speaking and did not know Aramaic (hence, Mark’s “translations” of Aramaic phrases). However, the Gospel is still very rooted in the Jewish worldview. The audience apparently did know certain Jewish terms (e.g., Satan, Beelzebul, Gehenna, Rabbi, Hosanna, and Amen). In particular they seem to have understood "christos", a word meaning "anointing" which Greek-speaking gentiles would have understood in reference to a hot oil rubdown, not a saviour commissioned by God. Its literary purpose appears to be: either to comfort a community undergoing persecution with the basic message, “Our Lord Jesus suffered as a servant, so you should expect to face the same"; or to address a spiritual arrogance that had developed in a Christian community (much as Paul had to with the Church in Corinth) with the basic message, “Our Lord Jesus suffered as a servant, so you should too”.

Characteristics of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark:

- Jesus is authoritative (people obey);

- Jesus is opposed from the outset;

- Jesus is misunderstood; in the entire Gospel, the only person who fully recognizes Jesus' identity as son of God is the centurion at the end;

- Jesus comes to be acknowledged by his followers, particularly Peter, as son of God;

- Jesus suffers (emphasized throughout);

- Jesus is vindicated (the tearing of the temple; the empty tomb).

The resurrection appearances in Mark are almost unanimously considered to be a later addition (16:9-20). The book ends with the empty tomb.

Matthew

The fact that Matthew does not explain many of the Jewish customs (as Mark and Luke do) suggests that his audience was at least partly Jewish and that the entire audience was familiar with many basic Jewish beliefs and practices. Many scholars suggest that this Gospel was written within and for the Christian community in Antioch, Syria. This was known to be a large, mixed Christian community in an urban area (which would explain the frequent use of “city” in Matthew instead of “village”). Furthermore, the earliest attestation of this Gospel in the Church was by a second-century church father in Syria (c. 110), Ignatius. Finally, due to a number of textual hints (e.g., reference to the king burning the city [22:7 reference to the destruction of Jerusalem?], the triadic formula [28:19; “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”], the condemnation of the free use of the title “Rabbi” [23:7], and the use of the phrase “to this day,” [27:8; 28:15]) suggest a date of composition after the Fall of Jerusalem and towards the end of the NT period, when the early Rabbinic movement had already taken center stage in Judaism. Thus, many date the book to c. CE 80 – 90. The literary purpose of the gospel appears to be to strengthen the faith of the author’s Jewish-Christian (with some Gentiles) community. In particular, on such evidence as the eleven appeals to a fulfilment of Old Testament prophecies, Matthew seems to want to demonstrate how Jesus was the authoritative Torah teacher, the second (greater) Moses, as it were, with the implication that early Christianity represented the proper interpretation of the Jewish Law (Torah) over against the emerging Rabbinic Judaism (which has many roots in the Pharisaic movement).

Characteristics of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew:

- Jesus is the authoritative Torah Teacher;

- Jesus is the second Moses;

- Jesus is the culmination of Israel's history;

- Jesus is the Jewish messiah;

- Jesus is the son of God (i.e., a particularly close intimate).

Luke

A late second century prologue prefixed to a copy of the Gospel reported that the Gospel was written in Greece and that the author (“Luke”) died there. The concentration in the second half of book of Acts on Paul’s career is suggestive of the audience of the whole two-volume work (Luke and Acts): churches that descended from Paul’s mission. The last lines of Acts (28:25-28) indicate that the future of the Gospel message lies with the Gentiles, suggesting a Gentile audience. The dropping of Aramaic terms and local Palestinian references (e.g., packed mud roofs, Herodians) supports a Greek-speaking, outside-Palestine audience. Greece is a suitable fit for Luke-Acts, probably c. CE. 85. The literary purpose of the book is so that Christians in the Roman world “may know the truth concerning the things about which [they had] been instructed” (1:4) The work of Luke-Acts is seemingly aimed at providing Christians in the larger Roman world with an assurance that their beliefs were not “subversive,” that is, in conflict with Roman governance, and that the Gentile Church was an intentional part of God’s plan for salvation — a plan that reached back to creation and extended to the conversion of the whole Roman world. Thus, the Gentile Christians — who had been evangelized by those who had not been eyewitnesses but whose Gospel had been received from eyewitnesses — could be assured that God’s salvation, which had moved towards Jerusalem (the first volume of Luke-Acts), had also moved towards Rome (second volume). Thus, Gentiles belong.

Characteristics of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke:

- Jesus is the deliverer for Jew and Gentile (with a focus on the Gentile);

- Jesus is the rejected prophet;

- Jesus is the righteous martyr.

John

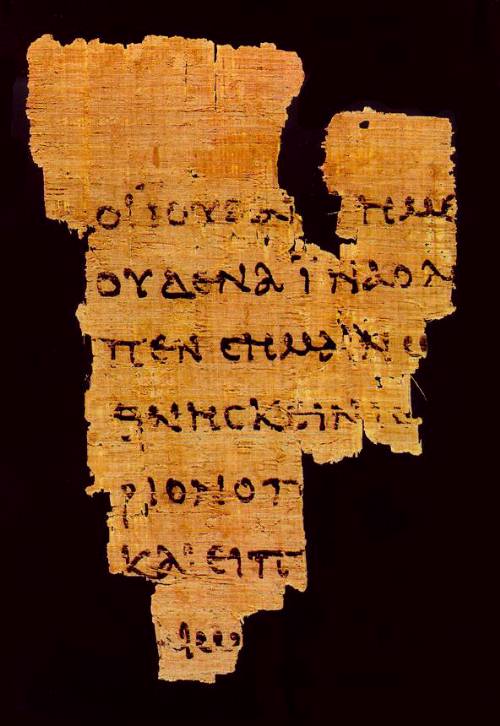

The image shows a portion of John 18 in the oldest known piece of a Biblical manuscript, believed to be early second century, now in the John Rylands Library, Manchester, U.K.

Both the Gospel writer and the audience appear to be Jewish. There are signs that this group of Jewish Christians may have been expelled from their local synagogue (see 9:22;  12:43; 16:2), an event that has pushed them to modify their own theology of Jesus. For example, the Jesus of the Fourth Gospel is explicitly divine and even pre-existent (see 5:16 – 18; 8:58; 10:30 – 38; 14:9; 17:5; 19:7; 20:28). The literary purpose of the Gospel of John is given at 20:31: “These are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” This encourages a community of Jewish Christians to hold fast to their faith in Jesus as the Messiah, Son of God, Word Incarnate while they suffer the pain of detachment from the Jewish community. Thus, this Gospel was more likely intended to strengthen insiders than to convert outsiders. One of the results of the cleaving between the Christian Jews and the non-Christian Jews is a heightened Christology: one of the book's clear aims is to present Jesus as divine.

12:43; 16:2), an event that has pushed them to modify their own theology of Jesus. For example, the Jesus of the Fourth Gospel is explicitly divine and even pre-existent (see 5:16 – 18; 8:58; 10:30 – 38; 14:9; 17:5; 19:7; 20:28). The literary purpose of the Gospel of John is given at 20:31: “These are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” This encourages a community of Jewish Christians to hold fast to their faith in Jesus as the Messiah, Son of God, Word Incarnate while they suffer the pain of detachment from the Jewish community. Thus, this Gospel was more likely intended to strengthen insiders than to convert outsiders. One of the results of the cleaving between the Christian Jews and the non-Christian Jews is a heightened Christology: one of the book's clear aims is to present Jesus as divine.

Other Gospels

There were other gospels — many, in fact. Based on the discussions in early Christian writings from the mid-second century CE on, there were at least seventeen Christian gospels floating around. Very prominent among the gospels that did not become part of the Christian canon are the Gnostic Gospels, such as the Gospels of Thomas, Mary Magdalene, Sophia, and Philip, as well as the recently famous Gospel of Judas; in addition, the Gospel of Peter shares some ideology with gnosticism but does not reflect full gnosticism.

“The Gnostics wrote a number of Gospels that fit their own belief system, and they attributed these works to various apostles. Their strategy was to write books as if apostles had written them, thereby gaining more credibility for their own beliefs. Some Gnostics claimed to receive new revelations of truth, and their beliefs became extremely influential in the second century. Orthodox Christian leaders grew very frustrated with the Gnostics’ teachings and with their habit of writing forgeries and attributing them to apostles. As a way of combating this threat, church leaders increasingly began to limit the number of books that were recognized as truly apostolic. Responding to the threat of heresy (deviation from or denial of established beliefs) began moving church leaders in the direction of establishing a New Testament canon” (Cosby, Chp. 5).

The NT canon and the dispute over "right thinking"

Ironically, in dealing with heretical teachings, some orthodox Christians fought fire with fire. If the Gnostics were writing books and letters in the names of apostles, then the orthodox could also play that game. Some began to write documents that specifically addressed second-century situations, but they wrote them as if they were penned by apostles in the first century. Thus, they adopted the ploy of gaining more credibility for their own writings by attributing them to apostles. Such pseudonymous documents became fairly common, and church leaders increasingly had to sort out which books were authentic and which were forgeries. Some of these documents are obviously forgeries, and the church had little difficulty dismissing them as fakes. However, others were written more subtly, using methods to make them appear to be authentic. These gave church leaders far more difficulty. Some they caught, some they didn’t.

The most obvious example is 2 Peter. The vocabulary and style of writing in 2 Peter differ radically from that found in 1 Peter. Numerous details in 2 Peter reveal that it represents a second-century historical setting, and you can read the details about these in any main-line commentary on the document. Although the apostle Peter was martyred about CE 65, 2 Peter relies heavily on the little New Testament document of Jude, which dates from the late first century. The fact that no second-century writers show any knowledge of the existence of 2 Peter provides additional evidence of its later date of composition. The first mention of 2 Peter comes in a text written about 220 CE. It is not until the fourth century that there is any evidence of widespread circulation of this text, and this seems to be the result of church leaders at that time accepting 2 Peter’s claim to have been written by the apostle Peter. These details compel virtually all New Testament scholars to agree that 2 Peter was written in the second century by someone who wanted to use Peter’s authority to attack a Gnostic heresy.

This anonymous writer reflects a later time when Christians were beginning to use the term “scripture” for apostolic ritings (2 Peter 3:15). This trend is seen more clearly in the writings of Irenaeus at the end of the second century; to refute false beliefs, he asserts the need to rely on apostolic oral tradition, which he calls the “rule” (canon) of faith. As far as we can tell, Irenaeus seems to have been one of the first people to use the terms Old Testament and New Testament with respect to two collections of documents that together form the Christian scriptures (Against Heresies 4.15.2; 4.28.1).

But other groups than the gnostics were making some waves. And why, out of the seventeen or so Gospels we know to have been written, were only four — Matthew, Mark, Luke and John — preserved by the emerging church?

When we look back for indications as to how the Gospels were regarded in the second century, we find first the testimony of Papias, who spoke of his acquaintance with Matthew and Mark, reporting that the latter was Mark’s preservation of Peter’s stories, and yet he voiced his preference for “living and abiding voices” who could recall stories told by the apostles, regarding those as of greater value than information he could glean from books. Clearly Papias, in the early 2nd century, showed no concern to narrow down which Gospels were acceptable. But many other groups did narrow down the acceptable list.

Efforts to limit the NT Canon

The Ebionites

One early Christian group was known as the Ebionites. “Ebion” is a Graecized form of the Hebrew word for “poor one,” אביון . Originally, it appears that this was a general reference to many of the Jewish Christians living in Palestine; in Roman 15:26, Paul mentions taking offering funds back to the Jerusalem Church for the benefit of "the poor." However, the term was later applied to a particular group of Jewish Christians whose beliefs were later considered to be “heretical.” It is possible that the origins of this group are referenced in one of Paul’s letters, the Letter to the Galatians. In that letter, as we will see later, Paul is engaged against a group of Jewish Christians known as the “Judaizers,” who were insistent that in order to be fully Christian, one must also become fully Jewish. This meant that they were compelling Gentile (non-Jewish) converts to become circumcised, to observe the Sabbath, to uphold Jewish dietary regulations, etc. So, the Judaizers believed that the basic nature of the Israelite covenant was still intact (as Matthew 5:17 – 18 implies). The Ebionites were very likely a similar strand, perhaps the same strand, of early Christianity. Also, being committed Jews in addition to accepting Jesus as the Messiah, they adhered to a strong monotheism (Deut. 6:4). This led them to conclude that Jesus had been a more typical Messiah than some other early Christians believed: he had been simply human and had had unusual (but not supernatural) gifts of righteousness and wisdom. In this way, he stood in the tradition of, say, the Hebrew Bible judges and prophets. While Jesus of Nazareth had been unique, and his death on the cross had been a final sacrifice that completely fulfilled the Israelite sacrificial cult, he was still a human, nothing more. This meant that they rejected a number of tenets of Christianity that were asserted in some of the Gospels and Pauline letters, such as the pre-existent Christ, the divinity of Jesus, and the virgin birth This in turn meant that they rejected Paul’s letters completely, do not appear to have had most of the other books of the NT, and considered only a short version of the Gospel of Matthew as authoritative (i.e., without the first 2 chapters, which present the virgin birth).

Justin Martyr

The next earliest evidence of anyone circumscribing which Gospels were authoritative and which were not comes in the middle of the second century, when a church leader named Justin Martyr spoke of “the memoirs of the Apostles,” which were read as scripture in his school in Rome and were the standard for identifying Jesus’ teaching. Based on the words he quoted when citing these “memoirs of the Apostles,” it is clear that they are the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, although only these three. Never does he quote from the Gospel of John.

Marcion

The reason Justin Martyr, in the middle of the second century, was concerned to identify which Gospels were authoritative, while Papias was not, is that just before the middle of the second century there arose a man named Marcion, a shipowner from northeast Asia Minor, who lived on the shore of the Black Sea. It used to be thought that he lived towards the end of the first century, but recent scholarship has found evidence to locate him closer to mid-century, assigning him a date of around 140, at least for his most active period. Obviously, Marcion did more than simply run a shipping industry. He promoted a version of Christianity that shared with gnosticism the belief that this world was created by an inferior god, whom he identified with “the Jewish god.” Jesus, on the other hand, had come to earth as the emissary of a higher deity. Marcion found his champion in Paul, whose first two chapters of the letter to the Galatians proclaimed the essence of the gospel for Marcion: Jesus had come to free people from the corrupt law revered within Judaism. Marcion’s lament was that this gospel had become corrupted by the defenders of Judaism, who had made modifications in even the ten letters of Paul that he accepted; and so Marcion took it upon himself to remove these. You can imagine, then, how Marcion treated a gospel like Matthew: he deplored it as pro-Jewish propaganda. In fact, the only gospel Marcion accepted was Luke, and only then after purging supposed additions intended to defend Judaism. The reaction to Marcion among many in the rest of the church was strong: Marcion was dead wrong about Judaism. Indeed, the God of Israel was the God and Father of Jesus. And so a rejection of Marcion’s ideas, together with all Gnostic forms of thought, arose.

Irenaeus of Lyon

The affirmation of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke as authentic was part-and-parcel of the rejection of gnosticism and its take on the "good news" of Jesus. But there was hesitancy about the Gospel of John, precisely because many gnostics were embracing it, finding it susceptible to an interpretation favourable to their tenets.

The first church official to include John in his collection of authoritative Gospels was a bishop by the name of Irenaeus, around the end of the second century. Consistent with Justin’s reaction, Irenaeus spoke of the gnostic-style Gospels as “apocryphal,” meaning that they were not authoritative the way that others were. The Gospels Irenaeus accepted were the Matthew, Mark, and Luke, plus John, as “scripture” (1.9.4; 2.26.1-2; 3.1.1 ), and he defended the four in the following way:

It is not possible that the Gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the church is scattered throughout all the world and while the “pillar and ground” of the church is the Gospel and the spirit of life, it is fitting, therefore, that she should have four pillars.…But that these Gospels alone are true and reliable and admit neither an increase or diminution of the aforesaid number, I have proved by so many such arguments.

Not only is the form of his argument peculiar and less than convincing from our vantage point, but also noteworthy is that Irenaeus takes a step we have no evidence of anyone taking prior to this: he asserts that the Christian message is, in effect, incomplete if only one gospel is used, and equally distorted if any others are consulted. It is this unity of four gospels — parallel to the four corners of the earth and the four winds — that Irenaeus argues is of paramount importance.

Crystallizing the NT Canon

Irenaeus’ view became, over time, the position throughout the Church, although no formal statement about which books made up the NT was adopted by the Church until the fourth century, during the era of Constantine.

The important point to underscore, though, is that the issue of which Gospels gained official approval arose only with the Church’s opposition to Gnosticism towards the end of the second century. It’s striking, for example, that Papias, at the beginning of that century, can still prefer oral reports to the written gospels he knew. And even when Irenaeus argued for four and only four gospels, it was not so much a judgment about which of the Gospels preserved the original sayings of Jesus or reports of his deeds, but about which Gospels expressed the understanding of the gospel message that came to be the touchstone for the Church’s life. That is what led to four and only four Gospels being preserved in the New Testament.

If we widen our scope to early Christian writings beyond the Gospels, it is clear that Marcion’s list (Luke plus ten Pauline letters) forced the other leaders to look more closely at their communities’ collection of scripture and consider their reasons for using them (Johnson, 1986: 536). The list by Melito of Sardis is witness to the early attempt to sort out the chaos. We can also see the assertions of Jerome, who argued against the Apocrypha, as part of this early, vigorous dialogue. Even the famous church father Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, had something to say on the matter.

To make a long story short, a number of “lists” of sacred Christian books appeared in the third and fourth centuries, but none carried any sort of authoritative status, and none listed all or only the 27 books of the NT as we know, until the Easter Letter by Athanasius in CE 367. Athanasius listed exactly the 27 books that have since been considered the extent of the NT Canon. After this, the North African Council of Carthage met in the late fourth century to ratify, or perhaps better, to recognize formally the New Testament canon of 27 books.

Summary

You will often read overviews of the process of canonization of the Christian Bible, or more specifically the NT, that suggest that the boundaries of this authoritative body of literature were established by contacts with beliefs that the proto-orthodox Christians concluded as heresy. Thus, disagreements with Marcion provoked the acceptance of the Old Testament, disagreements with both Marcion and the Ebionites provoked the acceptance of more than one gospel, whereas disagreements with the Gnostics provoked the limitation of the gospels to just four (and none overtly Gnostic!). Now, this all sounds quite plausible, but the caution is that it isn’t verifiable in any way. Perhaps a better conclusion might run like so: “it is fair to say that a discriminatory instinct was already at work in the late second century, but it was not systematic and yielded no sharp results.” In other words, perhaps the diversity itself was provoking conscious pondering about the community’s sacred literature, but there were no apparent movements to define it conclusively at this early time.

What can we say that is positive? Well, the conscious decisions of some of the movements that we considered to define theboundaries of their canonsindicate that this impulse was “in the water,” so to speak. In addition, the various confrontations almost certainly threw into sharp relief that diversity within Christianity and perhaps the need for a common denominator for the purposes of dialogue and doctrine. Finally, as Christianity grew away from its historical origin, as time passed, it is likely that greater value was accorded to documents that belonged to it earliest stages and that constituted its “ancestral records.” Also likely is the fact that the dissipation of oral traditions of Jesus and his followers, since the time span had become an obstacle, contributed to the recognized need for a canon of scripture by the end of the fourth century.

So, where does this bring us? Perhaps Athanasius’ Easter Letter of 367 was more of a start than an end in the process, and the process it reflects is the “recognition” not formation of the Canon of the Christian Bible. The actual formation of the NT Canon was largely an unguided, social process, by which communities shared their “sacred” literature with others and gradually developed a similar “library” of authoritative Christian works.