Some geography

Let's begin our overview with a geographical survey, which is a common approach. Many group the Indigenous peoples of North America into geographical areas, which are often equated with cultural areas. On this map, ten areas are identified. Of course each of these areas includes a number of distinct Indigenous nations. (On the next webpage I'll adapt this a bit, give a bit more detail, and raise a couple of cautions about this approach.)

Here follows a summary of the areas found in what's now the Canadian part of the map, as folks may have lived before European contact.

Here follows a summary of the areas found in what's now the Canadian part of the map, as folks may have lived before European contact.

Northwest Coast peoples were found along and near the coast of what are now British Columbia, Washington state, and Oregon. The coastal peoples had access to plentiful seafood, and the inland people had salmon. Cedar and other natural resources were abundant. The climate was reasonably mild. Indigenous peoples here generally lived in villages with cedar houses, had complex hierarchical social structures, and were relatively affluent.

Plains peoples lived in what are now the Canadian prairie provinces and adjacent U.S. states down to Texas. The buffalo was prominent in their economy; they hunted on foot until the Spanish introduced horses into North America in the 1500s. They also benefited from an abundance of smaller animals and wild plant life, and also often practiced domestic farming. Farmers lived in villages, and those on the hunt erected tipis as they moved. Extended families and sodalities (such as hunting alliances) were important social units.

Northeast peoples occupied what's now southern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime provinces, and adjacent U.S. states. Their diet was diversely based on foraging, hunting, fishing, and horticulture. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) lived in longhouses of logs, saplings, and bark; the Anishnaabe (such as the Ojibwe) typically lived in wigwams, domed rooms formed by arched wooden poles covered with mats, rushes, hides, or other materials.

Subarctic peoples were foragers who lived from the resources of boreal coniferous forests, with caribou, elk, moose, deer, and smaller animals, as well as vegetation such as wild berries, mushrooms, and root crops. Winters were long and harsh. The peoples lived in small temporary houses or semi-subterranean houses. Nuclear and extended families were fundamental social units. Social structures were egalitarian.

Arctic peoples depended on sea mammals such as seals, sea lions, walrus, and whales, hunted in kayaks, as well as fish, birds, land mammals. They also foraged plants. The peoples were mobile and were skilled at erecting small temporary housing such as igloos. The nuclear family was the basic social unit, and kinship groups were not so important.

Language groups

Although there are different ways of classifying Indigenous languages, and although languages of extinct groups, such as the Beothuk, are difficult to characterize, a broad working consensus has emerged under the influence of the multi-volume Handbook of North American Indians, published by the Smithsonian Institution. Eleven language groups including at least 65 languages and dialects are now generally recognized in Canada. Cree, Inuktitut, Anishnaabe and Oji-Cree, and Mohawk are often named as particularly robust languages with a goodly number of native speakers, but many other languages continue in use, though sometimes among only a few people. (Some endangered languages are being revitalized: see below.)

Northwest Coast peoples: This area has a disproportionate number of the surviving language families among the Indigenous peoples of Canada: Salishan, Na-Dene, Wakashane, Isolat, Penutian. Athapascan has traditionally been considered a language family but is now often listed the Na-Dene family. Haida is sometimes placed in the Na-Dene family though others consider it unique (a language isolate).

Plains peoples: The Cree and Blackfoot languages belong to the Algonquian family. The Assiniboine and Dakota languages are from the Sioux family.

Northeast peoples: Anishnaabe is an Algonquian language, as are its relatives such as Algonquin. Innu, Alikamek, and Mi`qmaq are also Algonquian language. The Iroquois languages of the Five Nations make up their own language family.

Arctic peoples: Inuktitut/Eskimo/Aleut is a large language group.

Today, according to Statistics Canada, the languages of the Algonquian family have the most native speakers speakers (about 145,000). About 35,000 speak Inuktitut. Altogether, about 215,000 people in Canada report an Aboriginal mother tongue to the Canadian census (which is by no means definitive).

Basic constitutional realities

Sovereignty. Indigenous peoples were self-governing and self-sustaining until well after contact with European peoples. Some nations, such as the Haudenosaunee, the Chippewas of Saugeen, and many or most nations in British Columbia, understand themselves as still sovereign, as they neither were conquered nor surrendered territory or self-government by treaty. Moreover, many Indigenous nations that have signed treaties understand treaty-making as a nation-to-nation process, and affirm that therefore their treaties recognize rather than extinguish their sovereignty. In settler constitutional law, however, the Crown in right of Canada has underlying title to all Canadian lands and exclusive sovereignty. In recent settler court decisions no legal rationale has been asserted for Canada's claim; it is something which simply happened — settler sovereignty "came out of the ether," as the prominent Ojibwe legal scholar John Borrows has put it.

This topic will be discussed on a future webpage.

The Canadian Constitution identifies three Aboriginal groups: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. The main political rationale for distinguishing First Nations from Inuit is that the latter don't come under the jurisdiction of the Indian Act, and haven't had reserves (although they have indeed sometimes been moved against their will).

Importantly, section 35, paragraph 1, of the Constitution Act of 1982 states, "The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed." Settler courts have both affirmed and restricted aboriginal rights in complicated ways. There is obviously a theoretical conflict between Indigenous and settler constitutional and legal jurisprudence in these areas. Where the conflict has become more than theoretical, settler governments, representing a much larger population and supporting a much stronger police and military force than Indigenous nations, have been able to impose their will on a "might makes right" basis.

First Nations: Canada recognizes about 630 First Nations bands or band governments (in the USA usually called "tribal governments"), representing about 850,000 people who self-identify to Statistics Canada as Indian. About 75% of these are registered under the Indian Act, which establishes a settler understanding of Indigenous identity. About half of registered Indians live on a reserve. Half of First Nations people are in Ontario and British Columbia. Statistics Canada counts 3100 reserves, but many are abandoned or seasonal. The largest reserve by far, in point of population, is the Six Nations of the Grand River, near Brantford, with about 25,000  members, of whom about half live on the reserve.

members, of whom about half live on the reserve.

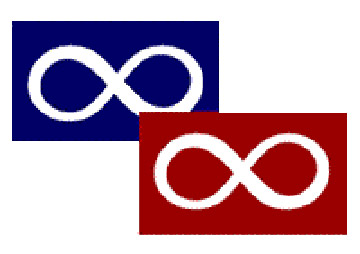

Métis: these are descendants of couples of mixed parentage, typically a white father and a First Nations mother. Originally the term was used where the father was French, but many Métis come from heritages with a part-English or Scottish background. This isn't a biological term; if it were, most of the population of British Columbia and Alberta would probably qualify as having mixed blood. Actually the definition of the term is subject to evolving case law and some controversies among Métis themselves, but those who can be most readily recognized as Métis grow up in a recognized, culturally distinct Métis community. About 450,000 people in Canada identify as Métis. The infinity sign on the Métis flag proclaims that the nation will live forever.

Inuit: About 60,000 Canadians identify as Inuit. The great majority live in the Arctic. The territory of Nunavut, created in 1999, is about 85% Inuit, and its official languages include Inuktitut and Innuinaqtun.

Language revitalization

In many places where only a few people speak the local language, programs of language  revitalization are being sponsored. In June 2019 the federal Indigenous Languages Act was proclaimed, to support and help fund this work. As one example, elders at Skidegate in Haida Gwaii created the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program in 1998 to expand knowledge of the language. Nine of the elders who have been teaching and preserving the language received honorary doctorates from Vancouver Island University in 2019. Here's a picture of them (plus the program coordinator, Kevin Borserio, back row at left).

revitalization are being sponsored. In June 2019 the federal Indigenous Languages Act was proclaimed, to support and help fund this work. As one example, elders at Skidegate in Haida Gwaii created the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program in 1998 to expand knowledge of the language. Nine of the elders who have been teaching and preserving the language received honorary doctorates from Vancouver Island University in 2019. Here's a picture of them (plus the program coordinator, Kevin Borserio, back row at left).

Go to: Page 3: Some ways to group Indigenous peoples in Canada