Grouping Indigenous peoples in Canada

A widespread approach to grouping Indigenous peoples in Canada is by geography. This approach reflects the fundamental relationship which most Indigenous peoples have to their land, and also an understanding that peoples in similar environments are likely to display patterns of similarity in their social life and culture. However, the former rationale doesn't necessarily support geographical grouping, and the second rationale isn't entirely true. Nevertheless, I'll follow an adapted approach here as a familiar way of initially organizing an introductory overview, except that I've identified the far-flung Cree nations in its own category:

I. Woodlands (Algonquians, Iroquoians)

II. Cree

III. Pacific northwest, western Alberta, western sub-Arctic

IV. Arctic

V. Métis (not geographically limited)

Woodlands

Two major language families are the Algonquians and the Iroquoians. The cultures of the nations in each of these groupingss are comparable as well as the languages. Note that the broad term "Algonquian" derives from the name of just one of these nations, the "Algonquins," a similarity which can cause confusion.

ALGONQUIANS

The Mi'kmaq nation occupies the Atlantic provinces and the Gaspé.

The Anishnaabe peoples include the Ojibwe [Chippewa] (including Mississaugas), Odawa, Potawatomi, Saulteaux, Nipissing): north and west of the Great Lakes, and beyond. The Algonquins, mainly in Quebec, and the Oji-Cree, are sometimes included in this category.

Heidi Bohaker of the University of Toronto, in her PhD thesis Nindoodemag: Anishnaabe identities in the eastern Great Lakes region, 1600 to 1900, completed in 2006, notes that these distinctions were made by Europeans, based on misunderstandings, for instance from conversations that lost something in the translation. She suggests that the way the Anishnaabeg self-identified was primarily by clan identity (nindoodemag), and not, for instance, by geographical residence or dialect.

The Innu (not to be confused with Inuit), include two peoples historically called the Montagnais and the Naskapi in northeast Quebec and western Labrador.

The Abenaki have homelands stretching across northern New England, southern Quebec, and the southern Maritime provinces.

Wolastokiyik or Maliseet occupy in the area along and around the Wolastoq (Saint John) River.

IROQUOIANS

IROQUOIANS

The Haudenosaunee peoples ("Iroquois") are the Five Nations of Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca. (Later, the Sixth Nation of the Tuscarora joined; but its language is not Iroquoian.) The map shows just some of the largest reserves. On European contact, the Finger Lakes, seen in this map but not labeled (you'll find them above and a bit to the left of the initials "NY"), and the Mohawk River valley to their east, were the most important Haudenosaunee territory on European contact; but most Six Nations peoples were expelled or pressured to alienate their land during and after the American Revolution.)

Huron (Wyandot, Wendat) peoples, like the Iroquois, were historically a confederacy of four (or more) nations in the area of Georgian Bay in Lake Huron; today the Huron/Wendat have a reserve at Quebec City, and three communities in the USA. Their languages is Iroquoian.

The Neutral Confederacy (Attawandaron) lived in the Niagara Peninsula and along the Grand River. The French named them "neutral" because they avoided taking sides in wars between the Iroquois and the Huron. They may have numbered 40,000 before European diseases devastated them. By 1653 they were integrated into the Haudenosaunee.

The Cree Nations

The Cree nations make up the largest First Nations grouping in Canada, numbering about 400,000. Their  territory extends from Labrador to Alberta and into the Northwest Territories. The Cree language belongs to the Algonquian family. The following distinctions mainly reflect differences in dialect:

territory extends from Labrador to Alberta and into the Northwest Territories. The Cree language belongs to the Algonquian family. The following distinctions mainly reflect differences in dialect:

- The "Swampy Cree" (in their dialect of Cree "Néhinaw" and other names), including a western branch sometimes called Muskegon, live mainly in the vicinity of James and Hudson Bays, and northeastern Saskatchewan.

- The "Moose Cree" or Moosonee live along the Moose River and beyond.

- "Plains Cree" (in their dialect of Cree "Néhiyawéwin" and other names) live mainly in Saskatchewan and Alberta, but also in Manitoba and Montana.

- "Woods Cree" ("Rocky Cree," "Bush Cree," and in their dialect of Cree "Nahathaway" and other names) live mainly in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta.

- Atikamekw live in the St-Mauricie of Quebec.

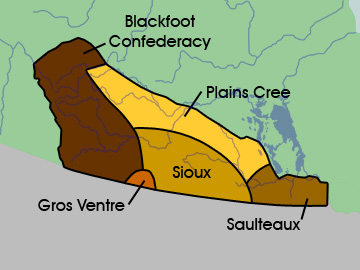

The Nakota nation is labeled "Sioux" here and originates in the Great Sioux Nation which  migrated from Woodlands Minnesota to the Great Plains. Today the Canadian Nakota are centred in Saskatchewan. A common English name for them is Assiniboine in the U.S., and Stoney in Canada.

migrated from Woodlands Minnesota to the Great Plains. Today the Canadian Nakota are centred in Saskatchewan. A common English name for them is Assiniboine in the U.S., and Stoney in Canada.

The Niitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy includes the Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), and Piikani (Peigan). They are called Blackfeet (rather than Blackfoot) in the U.S.A. In historic times, the Confederacy followed the buffalo in a territory roughly within the North Saskatchewan River, Yellowstone River, Rocky Mountains, and Cypress Hills.

The Saulteaux are Plains Anishnaabe. They were originally from the area of Sault Sainte Marie: hence the name Saulteaux.

Northwest (Pacific Coast and BC interior), western Alberta. the western sub-Arctic

The political, social, cultural, and linguistic picture here is very diverse and complex. There are over 200 First Nations in the area, and there are different ways to group them by languages, nationhoods, alliances, and political entities.

This map of traditional First Nations territories in BC was created (apparently) for the BC Ministry of Education. It's too big to load onto this page, but please open it and study it, since it's really quite special. It bears repeating that other map-makers would represent things differently. I've drawn up the follow table as a kind of index. It lists the territories named on this map, starting at the southern border of British Columbia and working north. The first column gives the name as spelled on the map. The second column indicates whether the territory is mainly on islands ("S" for sea), on the coast ("C"), or inland ("I"). The third column gives the names as they may appear in older publications. The fourth column gives the settler name for a town in or near the territory, which may be of use in referencing other maps.

Each of these territories has an entry in Wikipedia, usually with a pronunciation guide.

| Nation | A previous name |

A settler town name | |

| Nuu-chah-nulth | S | Nootka | Victoria |

| Coast Salish | C | (Grouping) | Vancouver |

| Nlaka'pamux | I | Thompson River | Lytton |

| Syilx | I | Okanagan | Penticton |

| Ktunaxa | I | Kootenay | Cranbrook |

| Stl'atl'imc | I | Lillooet | Lilloet |

| Kwakwaka'wakw | S,C | Kwakiutl | Fort Rupert |

| Wuikinuxv | C | Rivers Inlet | Rivers Inlet |

| Tsilhqot'in | I | Anahim Lake | |

| Secwepemc | I | Shuswap | Salmon Arm |

| Dunne-zaa | I | Beaver | Fort St John |

| Nuxalk | C | Bella Coola | Bella Coola |

| Heiltsuk | C | Bella Bella | Bella Bella |

| Haida | S | ||

| Haisla | C | Northern Kwakiutl | Kitamat |

| Dakelh | I | Carrier | Fort St James |

| Tsimshian | C | Prince Rupert | |

| Wet'suwet'en | I | Western Carrier | Prince George |

| Nisga'a | C | Terrace | |

| Gitxsan | I | Interior Tsimshian | Hazelton |

| Sekani | I | Prince George | |

| Tlingit | S,C | Sitka | |

| Tahltan | I | Iskut | |

| Dene-tha' | I | Slavey | High Level (AB) |

| Kaska Dena | I | Watson Lake | |

| Tagish | I | Carcross YU | |

| Tutchone | C | Haines Jct |

The Coast Salish peoples as represented on the map are not a single nation but a grouping of varied but related cultures.

The Kwakwaka'wakw peoples live on the northern part of Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland.

The Nisga'a nation has historic territory in the Nass Valley; the Tsimshian nation were historically located in the upper Skeena River valley and migrated downriver; the Gitxsan nation occupy ancestral land in the area of Legate Creek and the headwaters of the Skeena River. These are separate nations but are lingusitically related.

The Haida nation is a maritime territory in the area around the border with Alaska. These islands were formerly called the Queen Charlotte Islands.

The Tlingit nation, historically from southeast Alaska, now inhabit northwest BC and the southern Yukon.

The Dene or Athapaskan language family includes a number of languages spoken by a number of nations, many of them small in population, from Alaska to Texas.

The Dene peoples, a broad group including the Chipewyan, the Slavey, and others, live in a wide range across Alaska and northern Canada.

The Tagish nation lives around Tagish Lake and Marsh Lake, in the Yukon Territory. Their discovery of gold led to the Klondike Gold Rush, 1896–1899.

The Gwich'in nation (once called the Tukudh by Anglicans) live in the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and northern Alaska.

Many Cree, Anishnaabe, and Tlingit people live in the sub-Arctic as well.

The Arctic

The Inuit have almost exclusively occupied the Canadian Arctic for thousands of years. This area is above the treeline but there is plant cover. Their traditional language is Inuktitut, which has several dialects. The main groupings of the Inuit are the Labrador, Ungava, Baffin Island, Iglulik, Caribou, Netsilik, Copper (Kitlinermiut), and Inuvialuit. Earlier groupings, the Siglit and Sadlermiut, died out or were assimilated after being decimated by European disease.

Métis

The Canadian Constitution identifies the Métis as one of the three Aboriginal peoples of Canada. They trace their descent from mixed parentage in earlier centuries, most commonly in the huge territory, under Hudson Bay Company (HBC) control, that was called Rupert's Land, after Prince Rupert, the first Governor of the HBC. Thus today's Métis aren't themselves "half-blood" but are descended from mixed marriages many generations ago. In those days, mothers could be Cree, Anishnaabe, Mi'kmaq, Saulteaux, Menominee, Maliseet, or of another nation; fathers were French, English, or Scottish. The marriages were often, in the early days, à la façon du pays, which we might call common law. At first the French Métis and the Anglo-Métis (often called "countryborn") were distinct. Many early Métis lived near HBC trading posts and worked for the Company, and developed their own rich culture, typically Roman Catholic with strong Indigenous influences (or vice versa).

Go to: Part 4: Groupings of Christianities in Canada