Identifying denominational families

It's customary to divide Christian groups into denominational families. In lived life, however, Christian practice and belief is diverse within denominational families and overlap across them. And, as a sociological phenomenon, settler Christians are much more likely to change denominational affiliations today than they were a generation or two ago. Similarly, denominational institutional arrangements, which can seem stable and tidy from the outside, are less so from the inside. Institutions can be riven by controversies, power struggles, and schisms. Nevertheless, denominational division makes some sense in discussing the engagement of settler and Indigenous Christianities in Canada, since in many or most formal early contacts, settler missionaries and other agents almost always operated under the auspices of denominational judicatories. (A well known exception is William Duncan, a missionary among the Tsimshian who became disgusted with his Anglican superiors and bolted, or was forced out, in 1881.)

Until the 1960s Indigenous peoples in Canada were largely objects of settler Christian missions rather than fellow members with equal voice. Today, Christian denominations can be considered both settler and Indigenous in membership. Nevertheless, settler denominational identities have not transferred neatly into Indigenous societies. Indigenous Christians have negotiated the style of Christianity they preferred, often picking and choosing from various alternatives both within and among settler denominational. Furthermore, as settler repression grew stronger through the first half of the twentieth century, many Indigenous Christians looked for ways to evade, subvert, or defy settler models and authority, with long-term consequences. Most Indigenous Christians do profess denominational attachments, as we saw in the Statscan census data on the first page of this website. But they do not always share the same understandings and practices of affiliation of settler Christians.

Two more modern ecumenical groupings are noted at the end of this webpage because they have supported movements for Indigenous justice.

Roman Catholics

Roman Catholics are by far the largest Christian body in the world, with more members  than all other Christian groupings put together. Its authority structure descends from the Pope, the bishop of Rome, who is understood as the successor of Peter, who was personally appointed by Jesus to be the chief of the apostles and the rock of the Church. Virtually all formal settler Roman Catholic engagement with Indigenous peoples in Canada came under the auspices of bishops in Canada, or members of religious orders and missionary societies, who answered directly or indirectly to Rome. There was no single Canadian judicatory within the Roman Catholic Church guiding Indigenous policies and strategies. (Since 1943 there has been a Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, but although its importance has grown since the Second Vatican Council, 1962–1965, it does not direct the affairs of dioceses or religious orders.)

than all other Christian groupings put together. Its authority structure descends from the Pope, the bishop of Rome, who is understood as the successor of Peter, who was personally appointed by Jesus to be the chief of the apostles and the rock of the Church. Virtually all formal settler Roman Catholic engagement with Indigenous peoples in Canada came under the auspices of bishops in Canada, or members of religious orders and missionary societies, who answered directly or indirectly to Rome. There was no single Canadian judicatory within the Roman Catholic Church guiding Indigenous policies and strategies. (Since 1943 there has been a Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, but although its importance has grown since the Second Vatican Council, 1962–1965, it does not direct the affairs of dioceses or religious orders.)

Roman Catholic religious orders

Religious orders spearheaded most of the Roman Catholic Church's early settler engagement with Indigenous peoples after contact.

- The Jesuits (the Society of Jesus) were founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola with papal approval in 1540. They began sending French missionaries to Indigenous peoples in Canada in 1611.

- The Franciscans were founded by St. Francis of Assisi in 1209 as friars living without established means of support rather than as monks living in monasteries. Internal controversies divided the group into separate branches, such as the Recollects (a French group, known in French as the Récollets), who began sending missionaries to Canada in 1615, and the Capuchins, who arrived in Acadia in 1632. (The Recollects have not been an independent branch of the Franciscans since 1897.)

- The Ursulines, founded in 1535 by Angela Merici as a group of women devoted to prayer, teaching, and service to the poor, became a religious order in 1572. Ursuline nuns began working in Canada in 1639, when Marie de l'Incarnation began a mission with Indigenous girls.

- The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate ("OMI") led the extension of Roman Catholicism into western Canada. This order was founded in Provence in 1816 by Eugène de Mazenod with a focus on missions to the poor. Canada became their first foreign

mission in 1841, and from 1845 they were in the Canadian North-West, leading missions to Indigenous peoples as well as ministering to settler Roman Catholics. Many of the early Roman Catholic bishops in western Canada were Oblates. The order managed numerous Indian residential schools.

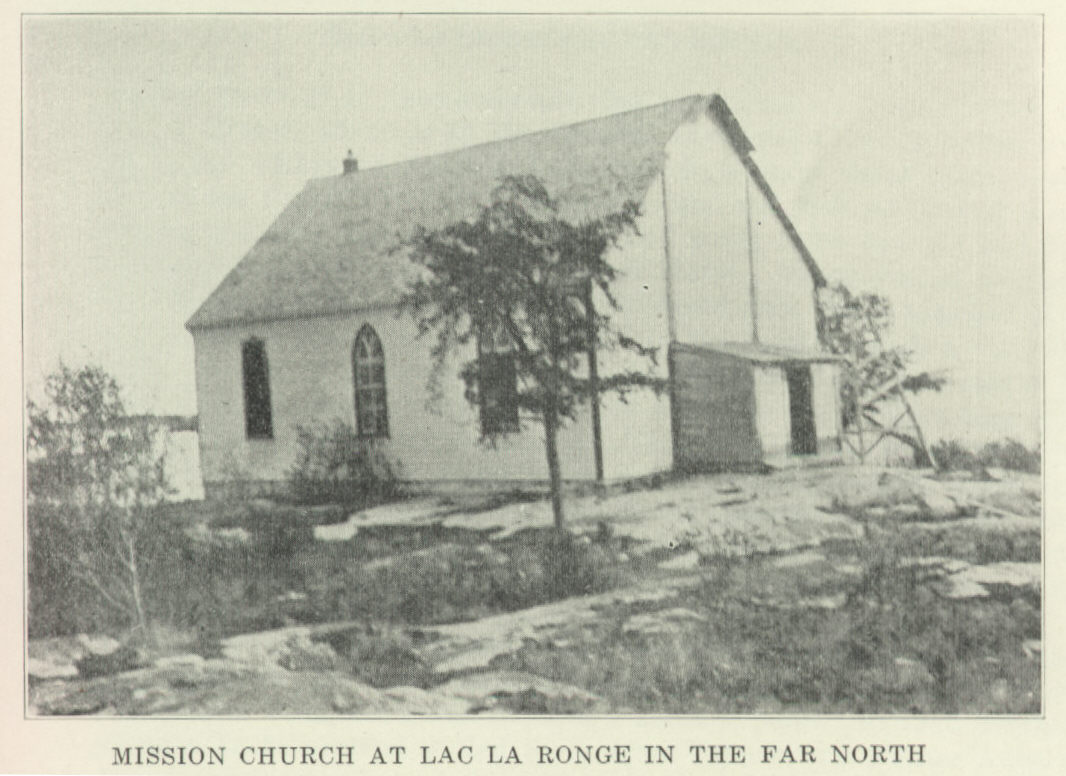

mission in 1841, and from 1845 they were in the Canadian North-West, leading missions to Indigenous peoples as well as ministering to settler Roman Catholics. Many of the early Roman Catholic bishops in western Canada were Oblates. The order managed numerous Indian residential schools. - The Sisters of Charity of Providence were founded in in 1843 in Montreal by a pious widow, Emilie Tavernier, to care for the poor, on the model of a group of women founded in 1633 by Vincent de Paul. From 1893 the sisters were working with the Oblate Fathers in the North-West to establish Indian residential schools. To the left: a Roman Catholic mission church in northern Saskatchewan, 1924.

When survivors of Indian residential schools began filing lawsuits in great numbers in the 1990s, there was no single Canadian Roman Catholic organization that could be identified as a defendant, since the managements of the Roman Catholic schools were accountable directly or indirectly to Rome. When the lawsuits were amalgamated into a class action and settled in 2006, the Roman Catholic signatories were 47 independent corporate "entities," including bishops and episcopal corporations, different provinces of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, different branches of the Sisters of Charity, and other religious orders.

The first Indigenous Roman Catholic priest (so far as I can find) was Father Edward Cunningham, OMI, a Métis ordained in 1890.

Kateri Tekakwitha, a Mohawk convert (1656–1680) who was canonized in 2012 as the first Roman Catholic Indigenous saint, has become the figurehead and icon of Indigenous Roman Catholicism. The Tekakwitha Conference has evolved as an Indigenous-led organization, incorporated in Montana in 1977; it sponsors an annual event for Native American Catholics and those who minister to them, to promote pride in Indigenous cultural traditions as well as Roman Catholic identity. It also sponsors local "Kateri Circles" for local Roman Catholic Indigenous devotion, evangelization, and service.

Church of England in Canada (since 1955 "the Anglican Church of Canada")

Until 1863 settler Canadian Anglicans understood themselves as an overseas branch of the Church of England, the constitutionally established church in England. Unlike in England, Anglicans were always a minority of the population in British North America. In 1863 an  English legal decision determined that Anglican churches in parts of the British Empire which were self-governing would need to be organized under local laws, not under English governance. Anglican affairs in what are now Ontario, Quebec, and the three Maritime provinces then came under the authority of a Canadian Anglican ecclesiastical province with several dioceses. After Canada bought the North-West from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870, a second Anglican ecclesiastical province, called Rupert's Land (after the first governor of the Company), was created in this territorial addition to Canada in 1875. The two provinces, Canada and Rupert's Land, were consolidated into a national church in 1893. A third Anglican ecclesiastical province called Ontario was formed from parts of the first two provinces in 1912, and British Columbia was recognized as a fourth Anglican ecclesiastical province in 1914.

English legal decision determined that Anglican churches in parts of the British Empire which were self-governing would need to be organized under local laws, not under English governance. Anglican affairs in what are now Ontario, Quebec, and the three Maritime provinces then came under the authority of a Canadian Anglican ecclesiastical province with several dioceses. After Canada bought the North-West from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870, a second Anglican ecclesiastical province, called Rupert's Land (after the first governor of the Company), was created in this territorial addition to Canada in 1875. The two provinces, Canada and Rupert's Land, were consolidated into a national church in 1893. A third Anglican ecclesiastical province called Ontario was formed from parts of the first two provinces in 1912, and British Columbia was recognized as a fourth Anglican ecclesiastical province in 1914.

Although settler Canadian Anglicans have governed their own ecclesiastical affairs since 1863, they usually had strong sentimental attachments to the "mother church" until a stronger sense of an independent Canadian nationality developed after World War II, and most settler Canadian Anglicans supported the perceived glories and destinies of the British Empire.

Settler Anglican engagement with Indigenous peoples in what is now Canada typically accompanied or followed the extension of British civil and commercial authority in new lands. Several influential settler Anglican missionaries were appointed and sponsored by bishops, but until 1920 the major player, especially in the North-West, was an English organization, Anglican in identity but formally independent of the Church of England, called the Church Missionary Society, founded in 1799. In principle its objective was to "indigenize" the mission church by converting and training  Indigenous peoples to become priests and bishops and take control. That didn't happen, partly because Indigenous territories were overrun by settler colonizers who kept authority in their own hands, and partly because most CMS missionaries were too Eurocentric to entrust the church to people who did not think in Eurocentric ways. However, some Indigenous Anglicans were ordained to the priesthood, beginning with a Cree worker named Sakachuwescam, Henry Budd, in 1853, pictured here.

Indigenous peoples to become priests and bishops and take control. That didn't happen, partly because Indigenous territories were overrun by settler colonizers who kept authority in their own hands, and partly because most CMS missionaries were too Eurocentric to entrust the church to people who did not think in Eurocentric ways. However, some Indigenous Anglicans were ordained to the priesthood, beginning with a Cree worker named Sakachuwescam, Henry Budd, in 1853, pictured here.

The CMS left the Canadian mission field in 1920. With some exceptions, notably in the north, settler ministries to Indigenous peoples waned after that, as funding decisions generally favoured the colonizers. However, with substantial government funding, a national Anglican agency called the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada operated Indian residential schools for children and teen-agers.

Second to the Roman Catholc Church, the Anglican Church of Canada maintains the largest ecclesiastical presence among Indigenous peoples. It has over 200 parishes with predominantly Indigenous membership. The first Indigenous bishop, Charles Arthurson, was conscrated in 1989. Seventeen other Indigenous bishops have been added since then. One diocese, Mishamikoweesh, located mainly in northern Ontario and eastern Manitoba, comprises only Indigenous parishes. The pastoral leader of Indigenous Anglicans in Canada is Archbishop Mark Macdonald, the National Anglican Indigenous Archbishop.

Methodists / the United Church of Canada

Methodists in Canada derived from a revival movement more or less within the Church of England led by John Wesley (1703–1791), one of its clergy. After his death the movement became a church independent of the Church of England, or, rather, it evolved into several churches with a complicated history of schisms and reunitings leading to a pretty definitive union in 1884. The Methodist Church of Canada became the largest constituent part in the "church union" project which in 1925 created the United Church of Canada.

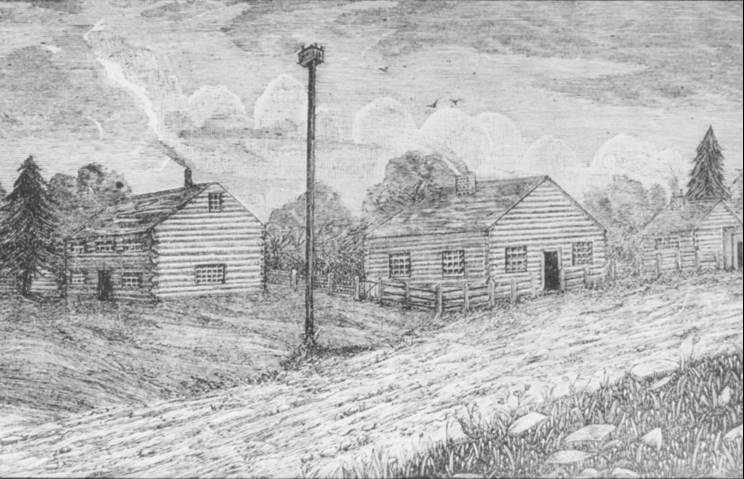

In the nineteenth century, Methodists were known for their revival meetings and evangelical fervour. It had considerable success among Indigenous peoples, particularly Ojibwe, in Upper Canada, and later in British Columbia, notably among the Heiltsuk nation. Its most famous early Indigenous convert was an Ojibwe of the Mississauga nation named Kahkewāquonāby, or Peter Jones (1802–1856). He was converted at a Methodist camp-meeting at the age of 21, and was later appointed an "exhorter" and missionary. He  brought dozens of Mississaugas into the Methodist Church, and established a mission for them on the Credit River in what is now the city of Mississauga, Ontario. This village (pictured right) prospered; it boasted homes, school, chapel, store, sawmill, blacksmith, and fields of wheat, corn, and rice. But it was undermined by the settler Indian superintendent, Thomas Anderson, and the community was forced to relocate to the Grand River, on land contributed by the Haudenosaunee. They then called themselves the Mississaugas of the New Credit, but in 2019 they changed their name to the Mississaugas of the Credit, referencing their earlier territory.

brought dozens of Mississaugas into the Methodist Church, and established a mission for them on the Credit River in what is now the city of Mississauga, Ontario. This village (pictured right) prospered; it boasted homes, school, chapel, store, sawmill, blacksmith, and fields of wheat, corn, and rice. But it was undermined by the settler Indian superintendent, Thomas Anderson, and the community was forced to relocate to the Grand River, on land contributed by the Haudenosaunee. They then called themselves the Mississaugas of the New Credit, but in 2019 they changed their name to the Mississaugas of the Credit, referencing their earlier territory.

In British Columbia the best known Methodist missionaries to the First Nations was Thomas Crosby (1840–1914) and Emma Crosby (1849–1926). Some resources are here.

After its creation in 1925 the United Church of Canada assumed the Methodist Indian residential schools. Statistics Canada in 2011 reported that fewer than 60,000 Indigenous people identified as United Church members.

Presbyterians

There were several Presbyterian groups in Canada, mostly deriving from the Church of Scotland. The four most important were united in 1875 as the Presbyterian Church in Canada. Their theological tradition was Reformed, which is to say, identified with the teaching of John Calvin (1509–1564) and those who developed it. Although they administered some missions and residential schools in "Indian country," their role was more modest than the first three named. In 1925, most Presbyterians joined the new United Church of Canada. About one in three Presbyterians remained outside church union and became the "continuing" Presbyterian Church in Canada. After 1925, only two Indian residential schools remained in Prebyterian hands. Statistics Canada in 2011 reported only 6,660 Indigenous Presbyterians in the country.

Baptists

This Christian group was so named because of its insistence on adult baptism of believers; it didn't recognize infant baptism. It grew out of sixteenth-century movements among English schismatics and European radical reformers. Baptists were highly decentralized; each congregation had considerable authority over its own affairs, though congregations typically networked through denominational associations. Canada has two major Baptist associations: Canadian Baptist Ministries, which connects four regional groupings ("conventions"), often called Convention Baptists; and the more conservative Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, often called Fellowship Baptists. Historically favouring the separation of church and state, Baptists have generally refused to accept state funding, and therefore almost totally excluded themselves from the administration of government-funded Indian residential schools. An exception was its Whitehorse Baptist Indian Mission School, funded by the federal Indian Affairs Branch.

Salvation Army

Connected historically with Methodist Christianities, the Salvation Army was founded as an inner-city, East London mission in 1865 by William and Catherine Booth, with the goal of  bringing the gospel to the destitute, and ministering to their spiritual and physical needs. The Booths transformed the local enterprise into a global mission around 1878; the first Salvation Army meeting in Canada was held in 1881; and Evangeline Booth, a daughter of the founders, was appointed commissioner for Canada. The group encountered considerable opposition from the longer established denominations, but its social message, gospel testimonies, and band music appealed to many, including Indigenous peoples, notably among the Tsimshian and Nisga'a nations, whom it began to reach in the 1880s. The Salvation Army continues to have a small but notable presence among inner-city Indigenous populations as well as in some Indigenous communities.

bringing the gospel to the destitute, and ministering to their spiritual and physical needs. The Booths transformed the local enterprise into a global mission around 1878; the first Salvation Army meeting in Canada was held in 1881; and Evangeline Booth, a daughter of the founders, was appointed commissioner for Canada. The group encountered considerable opposition from the longer established denominations, but its social message, gospel testimonies, and band music appealed to many, including Indigenous peoples, notably among the Tsimshian and Nisga'a nations, whom it began to reach in the 1880s. The Salvation Army continues to have a small but notable presence among inner-city Indigenous populations as well as in some Indigenous communities.

Mennonites

Named after the leadership of Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, Mennonite groups began settling southern Ontario from about 1776. Ethnically they were mostly identified with Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. They came to be known for their pacifist convictions and activism in issues of social activism and works of m ercy. A small minority of the settler population, they were not in a position to exercise control over Indigenous peoples, but as homesteaders they benefited from government politices of dispossession; the documentary "Reserve 107: Reconciliation on the Prairies" tells one such story, with an optimistic but inconclusive ending. Mennonites ran a handful of Indian residential schools, including Poplar Hill School in northwestern Ontario (pictured right). Today the Mennonite Central Committee is a vigorous advocate for Indigenous justice. An Indigenous–Settler Relations Program is active.

ercy. A small minority of the settler population, they were not in a position to exercise control over Indigenous peoples, but as homesteaders they benefited from government politices of dispossession; the documentary "Reserve 107: Reconciliation on the Prairies" tells one such story, with an optimistic but inconclusive ending. Mennonites ran a handful of Indian residential schools, including Poplar Hill School in northwestern Ontario (pictured right). Today the Mennonite Central Committee is a vigorous advocate for Indigenous justice. An Indigenous–Settler Relations Program is active.

Quakers

Formally called the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers were formed in the mid-seventeenth century in large part through the leadership of George Fox (1624–1691) of England. They came to be known for their skepticism of conventional church institutions and traditional Christian dogma, an inward, quietist spirituality, an experiential, extra-Scriptural approach to theology (seeking an "inner light"), pacifism, and progressive social activism. The last element made them disproportionally influential on public policy, including policies regarding Indigenous peoples, relative to their small membership numbers. Accordingly, Quakers are included here not because many Indigenous peoples in Canada became Canada (they did not), but because they challenged the victimization of Indigenous peoples. (They did not, in the nineteenth century, challenge the colonial consensus that, for their own good, Indigenous peoples needed to be "civilized" and "Christianized" — that is, needed to become more like Europeans.) Quakers were the main force in the "Aborigines' Protection Society" (1837–1909), based in England, that advocated for Indigenous legal and political rights (but not cultural rights) in North America, Australasia, and South Africa. Their 1840 report on Upper Canada, available on-line, which exposed the damage done to First Nations peoples by land speculators, self-interested politicians, and other settler colonizers, won the sympathy of British Parliamentarians. More recently, in 1974 Canadian Quakers established the Quaker Indigenous Affairs Committee in the wake of an armed confrontation in Kenora; it has continued to advocate for Indigenous justice.

Moravian Church

The Moravian Church is rooted in a pre-Reformation religious movement in Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic) inspired by Jan Hus (1372–1415). In 1722 an underground remnant of this group, facing persecution in Moravia, sought sanctuary on the estate of a nobleman in what is now Saxony, Count von Zinzendorf (1700–1760). Other refugee groups followed, and developed a village on the estate called Herrnhut. A religious renewal followed, and Herrnhut became the centre of an evangelistic and missionary movement. Groups of lay Moravian missionaries began evangelizing Indigenous peoples in North America, including the Lenni Lenape (Delawares) in Pennsylvania in 1741. After a Munsee branch of the Lenape were massacred during the American Revolution, they sought refuge in Upper Canada, accompanied by their Moravian missionary. Their descendants are now based at the Moravian of the Thames Reserve. Other Moravian missionaries arrived in Labrador in 1764, and developed the first Christian mission to the Inuit in what is now Canada. In the nineteenth century hundreds of Inuit were attached to Moravian mission stations in Labrador; at any one time there were thirty or forty Moravian missionaries in Labrador, usually German, all of whom learned Inuktitut. The Moravians developed trading operations and became a dominant force in Labrador socially, economically, and religiously. They published Inuktitut grammars and lexicons, and operated residential schools which taught Inuktitut literacy. However, like other Christian missions, it suppressed many traditional Inuit practices as "heathen." In the twentieth century the ministry moved from German-speaking Moravians to the British branch of Moravians. For many reasons it has waned since World War I. Many of their services were transferred to the International Grenfell Association and to the government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Two Moravian residential schools were part of a settlement agreement for survivors, reached in 2016.

Pentecostals

The classic date identifying the beginning of this movement is 1906, when a worship meeting in Los Angeles broke out into dramatic manifestations of gifts of grace from God's Holy Spirit, but that event had a pre-history and led to later developments. The name refers to an event recorded in Acts 2, when on the day of Pentecost (the fiftieth day after Christ's resurrection) the Holy Spirit fell on thousands of people gathered in Jerusalem so that they began speaking in foreign languages unknown to them. Pentecostals took a fundamentalist approach to Scripture, expected an imminent return of Jesus Christ to this world, looked for strong personal experiences of God's grace, and were eager to convert people to Christianity. Over the last century they have actively evangelized Indigenous communities across Canada. One of its departments, for instance, the Northland Mission (1943–1996), was founded by a missionary pilot who itinerated to remote Ojibwe, Cree, and Oji-Cree communities in northern Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba, and the Northwest Territories; it also oversaw a Bible training institute. It remained tightly controlled by its Euro-Canadian leadership. It was succeeded by "Aboriginal Pentecostal Ministries" which has affirmed Indigenous leadership.

The classic date identifying the beginning of this movement is 1906, when a worship meeting in Los Angeles broke out into dramatic manifestations of gifts of grace from God's Holy Spirit, but that event had a pre-history and led to later developments. The name refers to an event recorded in Acts 2, when on the day of Pentecost (the fiftieth day after Christ's resurrection) the Holy Spirit fell on thousands of people gathered in Jerusalem so that they began speaking in foreign languages unknown to them. Pentecostals took a fundamentalist approach to Scripture, expected an imminent return of Jesus Christ to this world, looked for strong personal experiences of God's grace, and were eager to convert people to Christianity. Over the last century they have actively evangelized Indigenous communities across Canada. One of its departments, for instance, the Northland Mission (1943–1996), was founded by a missionary pilot who itinerated to remote Ojibwe, Cree, and Oji-Cree communities in northern Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba, and the Northwest Territories; it also oversaw a Bible training institute. It remained tightly controlled by its Euro-Canadian leadership. It was succeeded by "Aboriginal Pentecostal Ministries" which has affirmed Indigenous leadership.

International Grenfell Association

This was not a church, but a charitable organization that provided health care, education, cooperative stores, business opportunities, and other social services for northern Newfoundland and the Labrador Coast. It was developed in the 1890s by Sir Wilfrid Grenfell (1865–1940), a medical missionary for a non-denominational Christian organization which didn't share his ambitious vision. Originally intended for non-Indigenous peoples, the IGA later opened three Indian residential schools whose survivors reached a settlement agreement in 2016.

Canadian Council of Churches

This ecumenical fellowship of Christian churches was established in 1944. Unlike the World Council of Churches, it includes the Roman Catholic Church (through its conference of bishops). It sponsors theological dialogue, collaborative action and advocacy for peace and social justice, Christian education, and an annual week of prayer for Christian unity. In recent years it has given particular attention to issues of Indigenous justice, including educational events and resources, dialogue, and political advocacy.

Kairos

This ecumenical organization for social justice was formed in 2001 by bringing together a  number of inter-church coalitions with overlapping goals. One of these groups was the interdenominational Aboriginal Rights Coalition, formed in 1989. This in turn was a successor to a group called Project North, founded by mainline churches in 1975 to advocate for Aboriginal land rights (particularly, at first, in the Mackenzie River Valley) in cooperation with Indigenous groups. In 1997 the Aboriginal Rights Coalition developed the "Blanket Exercise," a 90-minute participatory educational event for settler Canadians that raises awareness about the history of the dispossession of Indigenous lands by settler colonizers. The Blanket Exercise is now administered under the auspices of Kairos, and is one of its best known activities.

number of inter-church coalitions with overlapping goals. One of these groups was the interdenominational Aboriginal Rights Coalition, formed in 1989. This in turn was a successor to a group called Project North, founded by mainline churches in 1975 to advocate for Aboriginal land rights (particularly, at first, in the Mackenzie River Valley) in cooperation with Indigenous groups. In 1997 the Aboriginal Rights Coalition developed the "Blanket Exercise," a 90-minute participatory educational event for settler Canadians that raises awareness about the history of the dispossession of Indigenous lands by settler colonizers. The Blanket Exercise is now administered under the auspices of Kairos, and is one of its best known activities.

Go to: Page 5: Filters and futures: researching Christianities and colonialism