Filters for understanding the past

Historians and others often look at the past through the filter of a large general story or "meta-narrative." Individual episodes and experiences are then interpreted in consistency with the larger meta-narrative. As an obvious example, early settler missionaries who thought of themselves as culturally superior and of Indigenous peoples as primitive readily interpreted their experience of Indigenous peoples through this meta-narrative. To their eyes, Indigenous social practices that in actuality were quite complex and sophisticated seemed simple and primitive.

Here's a schema of how historians and others have written and spoken about our topic — the engagement of Indigenous peoples and settlers around Canadian Christianities. Most are meta-narratives, although one is at root an anti-meta-narrative!

A classic missionary narrative

In this story, European missionaries, motivated by self-sacrificial discipleship, passion for the gospel, and a sense of adventure, went out to convert the Aboriginal peoples of Canada to their form of the Christian faith, which was better than competing forms of the Christian faith, and also, needless to say, better than Indigenous spirituality and practices.

The earliest written example of this narrative in the western hemisphere may be the description of the culture of the Taino peoples written in 1496 by Friar Ramón Pané, under commission by Christopher Columbus. It was based on his observations and interviews with this Caribbean people. It is thoroughly Eurocentric; the author's filter is that the Taino are "simpe ignorant people who know not our holy faith." Over the next several centuries there followed many hundreds of reports of Indigenous peoples in the New World written by missionaries, or from a point of view sympathetic to the missionaries; and as a general rule they followed the same pattern. Many of these writers made observations about Indigenous beliefs and practices, strained through their net of biases. Few recognized the realities of Indigenous spirituality, which were largely invisible to people who understood religion to have doctrinal creeds, written scriptures, structured institutional organizations, and special permanent buildings, as Christianity had.

A scientific evolutionary narrative

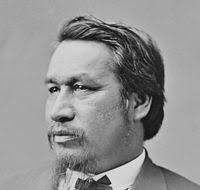

In this story, Christian missionaries aren't the heroes; the anthropologists and their allies are. Here human societies progress in linear fashion from savage, to barbarian, to civilized, to highly sophisticated. Indigenous societies are on the low end, and European society is wonderfully advanced. People in advanced societies can help people in primitive societies to modernize. This was supposed to be a scientific, empirical, value-free interpretation of things.  Lewis Henry Morgan's League of the Iroquois (1851) represents the first "scientific" anthropological ethnology of an Indigenous group. Morgan based his study on intensive field work, language study, and the information of a Seneca ethnologist named Ely Parker (pictured at right). However, the study was certainly not as value-free as Morgan imagined, since he valued his own culture as more worthy. Although the scientific anthropologists distanced themselves from the missionaries, nevertheless many missionaries combined this story with their own: they were to be agents both of civilization and of Christianization. (The evolutionary approach was firmly and creatively challenged by James Mooney's Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890 (1896), which made cross-cultural comparisons that demonstrated the universalities of human cultures, and similarities in social practices and understandings between Indigenous and European peoples.)

Lewis Henry Morgan's League of the Iroquois (1851) represents the first "scientific" anthropological ethnology of an Indigenous group. Morgan based his study on intensive field work, language study, and the information of a Seneca ethnologist named Ely Parker (pictured at right). However, the study was certainly not as value-free as Morgan imagined, since he valued his own culture as more worthy. Although the scientific anthropologists distanced themselves from the missionaries, nevertheless many missionaries combined this story with their own: they were to be agents both of civilization and of Christianization. (The evolutionary approach was firmly and creatively challenged by James Mooney's Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890 (1896), which made cross-cultural comparisons that demonstrated the universalities of human cultures, and similarities in social practices and understandings between Indigenous and European peoples.)

A narrative of Indigenous disappearance

In this story, Indigenous people are going to disappear, unable to resist the march of modernity. Among anthropologists, this was usually a story told with regret; Indigenous cultures were lively and honest and fascinating, and they would be missed. Franz Boas (1858–1942), "the father of American anthropology," was the best known and most influential of what have been called "salvage anthropologists." while based at Columbia University and the University of California, he conducted numerous field studies of Indigenous peoples, notably in the Arctic and in British Columbia. He rejected cultural evolutionism, and saw something to value and appreciate in all cultures. Persuaded that Indigenous peoples in North America would fall victim to modern western society, he wrote detailed descriptions of Indigenous practices to establish a permanent record of them before they disappeared: hence "salvage anthropology." He applied the metaphor that the books he wrote were boxes in which the relics of an Indigenous people's culture could be stored. Accordingly, he took little interest in processes of cultural change. In fact, he preferred to study communities that seemed ethnically homogeneous and cultura lly isolated, and he often seems to have assumed that Indigenous societies were unchanging before European contact. A problem with this approach is that everything of real value in Indigenous culture was frozen in time, destined to disappear. A characteristic First Nations response to this approach has been: "They write as if there were no living Indians any more." (A critic of this approach was Alfred Goldsworthy Bailey (1905–1997), pictured left, a professor of history at the University of New Brunswick. His book The Conflict of European and Eastern Algonkian Cultures, 1504-1700: A Study in Canadian Civilization (1937; 1969) took an interest in processes of cross-cultural influence, historical change, and religious engagement.)

lly isolated, and he often seems to have assumed that Indigenous societies were unchanging before European contact. A problem with this approach is that everything of real value in Indigenous culture was frozen in time, destined to disappear. A characteristic First Nations response to this approach has been: "They write as if there were no living Indians any more." (A critic of this approach was Alfred Goldsworthy Bailey (1905–1997), pictured left, a professor of history at the University of New Brunswick. His book The Conflict of European and Eastern Algonkian Cultures, 1504-1700: A Study in Canadian Civilization (1937; 1969) took an interest in processes of cross-cultural influence, historical change, and religious engagement.)

A classic anti-missionary narrative

In this story, Europeans pressured and coerced Aboriginal peoples, who were either helpless or gullible, into accepting the religion and values of the colonizers. Missionaries were one part of this process, along with politicians, courts, armies, and other colonial agents. This approach has been called "inverse colonialism." Like the colonizers' missionary perspective, it sees Indigenous and western as opposites, but where the missionary regarded the western as in every way superior to the Indigenous, this counter-story sees the Indigenous as in every way superior to the western. Vine Deloria Jr. (1933–2005), a member of the Oglala Lakota nation who was a professor at the University of Arizona and the University of Colorado, and whose father was an  Episcopal Church missionary priest, was an eminent advocate of this view. In a book on settler and Indigenous religion called God is Red (1973) he affirmed a “great gulf” between “traditional Western thinking about religion and the Indian perspective,” two traditions which were "polar opposites in almost every respect.” The old-style European missionary might agree so far. But Deloria, inverting the missionary's perspective, presented Native spirituality as wise and generative, and Christianity as superstitious and destructive; Native spirituality as connected to the life cycles of the natural world, Christianity as alienated from nature and fearful of death; Native spirituality as in touch with the Creator, Christianity as anxious about a temperamental, egoistic, judgmental God. (A Candian example of this approach was James Dumont, an Anishnaabe scholar who founded the Native studies program at Laurentian University.)

Episcopal Church missionary priest, was an eminent advocate of this view. In a book on settler and Indigenous religion called God is Red (1973) he affirmed a “great gulf” between “traditional Western thinking about religion and the Indian perspective,” two traditions which were "polar opposites in almost every respect.” The old-style European missionary might agree so far. But Deloria, inverting the missionary's perspective, presented Native spirituality as wise and generative, and Christianity as superstitious and destructive; Native spirituality as connected to the life cycles of the natural world, Christianity as alienated from nature and fearful of death; Native spirituality as in touch with the Creator, Christianity as anxious about a temperamental, egoistic, judgmental God. (A Candian example of this approach was James Dumont, an Anishnaabe scholar who founded the Native studies program at Laurentian University.)

Deloria also took on the anthropologists, who were second only to the church as a target for his criticism. In Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (1969) he rocked the academic establishment with a very funny but very bitter chapter on anthropologists, for whom "people are objects for observation, people are then considered objects for experimentation, and for eventual extermination." (Actually, even the old-style anthropology had more "insider" authorship than the westerners always acknowledged; for instance, Boas depended as much on his Kwakwaka'wakw collaborator George Hunt as Morgan had on Parker. The anthropologists, not always aware of diversities in Indigenous opinion, were much influenced by the version of things that their Indigenous informants gave them.)

A narrative of Indigenous agency

This is the first story where Indigenous people are actually wise, resourceful, and strategic. It rejects the premise, once very common, that "Europe produced history and Natives submitted to it," as Brett Christophers has wittily phrased  it. Instead, this is the story of how the colonized, in spite of all the odds against them in seriously imbalanced power relationships, have been canny in negotiating what they received and adapted from the colonizers. They have been creative and resilient in processes of cultural change. They have known how to protect their interests so far as possible against a repressive militant colonialism. For instance, in the early colonial fur trade, Indigenous peoples were not simply go-fers for settler entrepreneurs, but were shrewd participants and leaders. Similarly, the Métis scholar Brenda Macdougall (pictured to the right) showed that a Métis community in northwestern Saskatchewan in the nineteenth century understood community in ways that had resonances with Roman Catholicism but remained profoundly rooted in Cree spirituality, which was thus by no means displaced. We'll see many further examples on later pages of this website.

it. Instead, this is the story of how the colonized, in spite of all the odds against them in seriously imbalanced power relationships, have been canny in negotiating what they received and adapted from the colonizers. They have been creative and resilient in processes of cultural change. They have known how to protect their interests so far as possible against a repressive militant colonialism. For instance, in the early colonial fur trade, Indigenous peoples were not simply go-fers for settler entrepreneurs, but were shrewd participants and leaders. Similarly, the Métis scholar Brenda Macdougall (pictured to the right) showed that a Métis community in northwestern Saskatchewan in the nineteenth century understood community in ways that had resonances with Roman Catholicism but remained profoundly rooted in Cree spirituality, which was thus by no means displaced. We'll see many further examples on later pages of this website.

This story-line is part of an approach often called post-colonialism. (The "post" in "post-colonialism" in this context does not imply that colonialism is in the past. It means that colonialism is no longer seen as inevitably permanent.) A major impetus for post-colonial thought was Edward Said's Orientalism (1978), which showed how European writers and scholars down to his own time viewed the "Oriental" world through stereotypes and invented knowledge that reinforced their sense of their own cultural superiority and justified colonialism in the Middle East and India. This same imperialist ideology was applied by the colonizers of North America.

The main principles of the post-colonial perspective can be summarized in this way:

Life involves change and adaptation to change. Personal and social identities aren't permanent. What it means to be French or Cree or anything else can't be "essentialized." Identities are negotiated.

Indigenous people were creative and resilient in negotiating the cultural change that colonialism brought.

Indigenous people retained agency in colonial relationships.

Through inter-marriage and cultural engagement, overlapping identities emerged that were neither purely Indigenous nor purely settler.

Inter-cultural engagement happened in an infinite number of particular ways. There are no accurate unqualified generalizations and meta-narratives.

In particular, related to our topic, "becoming Christian" could have no fixed definition. There was a myriad of expectations among settler missionaries about the conversion of Indigenous peoples; there was a myriad of ways in which Indigenous Christians came to think of themselves as Christian, and chose to express their Christian faith.

Ways of using knowledge to engage the future

We are at a historical juncture where western academics and Indigenous elders and knowledge-keepers are talking to each other respectfully and collaborating in promising ways. And since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission published its 94 "Calls to Action" in 2014, issues of Indigenous justice and ways of knowing have been on the agenda of virtually every university, college, and research institution in Canada.

Two approaches can be particularly noted.

Engaged scholarship

In the 1960s western scholarship was questioniong earlier academic standards of value-free objectivity. Wasn't objectivity an illusion? People's perceptions and values are inevitably shaped by their cultural and social positioning. At school, when people read histories and social scientifc theory, they were reading the ideas and selective interests and socially conditioned values of the dominant voices: tenured and tenure-track white male academics in socially prestigious universities, who were writing to impress other tenured and tenure-track male academics. In these histories, where were women, visible minorities, blue-collar workers, the global south, — and Indigenous peoples? These marginalized groups began making a place for themselves in the factories of knowledge. By the 1970s there had emerged a variety of subaltern studies: for example, women's studies, black studies, labour studies, third-world studies, and Native studies (as it was called at first). And these new academic disciplines in turn mirrored movements in the wider society  that were advocating for the just treatment of historically marginalized groups. These new disciplines were not to be totally dominated by first-world white male academics for whom everyone else was "the other." They were to involve "the others" themselves. And many of the white male academics (not all!) allied with the newcomers, and took delight in the broadening of their intellectual horizons. And, together, they identified issues of justice where reliable research might guide political decision-making.

that were advocating for the just treatment of historically marginalized groups. These new disciplines were not to be totally dominated by first-world white male academics for whom everyone else was "the other." They were to involve "the others" themselves. And many of the white male academics (not all!) allied with the newcomers, and took delight in the broadening of their intellectual horizons. And, together, they identified issues of justice where reliable research might guide political decision-making.

As an important Canadian example, throughout the twentieth century the Nisga'a people had been seeking the settler government's recognition of their land claims. in 1967 Frank Calder, a Nisga'a elder, pictured at left (who was also, incidentally, a graduate of the Anglican Theological College in Vancouver), filed a law suit for the recognition of Aboriginal land rights. Anthropologists were recruited to demonstrate to the courts that the Nisga'a had occupied their lands since well before European contact, and recognized their attachment to the land. They also challenged the provincial government's cultural bias. The case "Calder v British Columbia (Attorney General)" worked its way to the Supreme Court of Canada, which in 1973 published its ground-breaking decision that Aboriginal land title pre-dated European settlement.

The scholarly and popular publications, expert courtroom testimonies, research foir legislative committees, and other interventions of Indigenous and settler academics (and church groups) have become a familiar element in the formulation of public policy on Indigenous issues.

Indigenous and settler ways of knowing

Western academic theory and practice have so far been dominating the study of our topic — the engagement of Indigenous and settler peoples around Christianities. But Indigenous ways of knowing have also been claiming their place in the public and academic forums of Canada.

What are Indigenous ways of knowing? Of course there's no single Indigenous approach to truth, just as there's no single European approach to truth. In any event, Indigenous and settler peoples have been connected so long that their ways of knowing cannot be neatly separated out.  But diverse Indigenous writers (some of them identified in the left-hand column, including Margaret Kovach, pictured to the right) have suggested that some of the following elements are important in Indigenous ways of knowing:

But diverse Indigenous writers (some of them identified in the left-hand column, including Margaret Kovach, pictured to the right) have suggested that some of the following elements are important in Indigenous ways of knowing:

-

Avoiding binary (Aristotelian) and dichotomous analysis; preferring a 360-degree vision that looks at things from multiple perspectives;

-

Using Indigenous languages as well as European languages;

-

Respecting the truth in other people's cultures, and questioning the familiar assumptions in one's own;

-

Building good relationships across cultures, perhaps over many years;

-

Listening to people, and listening extra hard to the elders, since Indigenous knowledge comes in a personal way, not in an independent, objective form;

-

Participating in ceremonies, as invited;

-

Recognizing the importance of story;

-

Carefully observing and connecting with the environment, rather than probing for natural laws and abstract insights;

-

Seeing from a decolonizing perspective;

-

Being open to spirit.

In different situations, some of these principles may be consistent with western ideas, and others may come into conflict. In particular, much western historical scholarship is intensely text-based, and many western scholars have (at least until recently) usually devalued the oral traditions of Indigenous cultures. Theologians can have useful things to say in this area, since the Bible is both text and a record of oral tradition.

The next step is the further collaboration of Indigenous and settler scholars, bringing together wisdom, experience, and ways of knowing from their diverse backgrounds and resources. On the one hand, Indigenous scholars are coming into the academy in ever  increasing numbers as historians, anthropologists, specialists in Indigenous studies, and experts in the theological disciplines. If settler academics can help them resist the pressure to think like western scholars, they will broaden our horizons immensely. On the other hand, settler scholars are venturing more and more into Indigenous communities, not as if they are touring territories of exotic otherness, but as seekers of truth. A fine example is the book which Leslie Robertson, an anthropologist at the University of British Columbia, researched and wrote in collaboration with, and at the invitation of, an extended Kwakwaka'wakw family, recovering the truths about a matriarch in their family tree — a privileged elder, a long-time president of the local Anglican Women's Auxiliary, and, some said, a collaborator with colonialism and a renegade from her people. And in 2018 the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Councl of Canada, one of the government's major funding arms, funded a (somewhat hurried and imperfect) project to advance Indigenous and settler collaborative research.

increasing numbers as historians, anthropologists, specialists in Indigenous studies, and experts in the theological disciplines. If settler academics can help them resist the pressure to think like western scholars, they will broaden our horizons immensely. On the other hand, settler scholars are venturing more and more into Indigenous communities, not as if they are touring territories of exotic otherness, but as seekers of truth. A fine example is the book which Leslie Robertson, an anthropologist at the University of British Columbia, researched and wrote in collaboration with, and at the invitation of, an extended Kwakwaka'wakw family, recovering the truths about a matriarch in their family tree — a privileged elder, a long-time president of the local Anglican Women's Auxiliary, and, some said, a collaborator with colonialism and a renegade from her people. And in 2018 the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Councl of Canada, one of the government's major funding arms, funded a (somewhat hurried and imperfect) project to advance Indigenous and settler collaborative research.

This is a promising future.

Some Indigenous scholars in Canada whose research includes Christianity

These are a few Indigenous scholars who focus on Christianity, or include Christianity in their research:

- Ray Aldred, a Cree theologian at the Vancouver School of Theology.

- Karl Hele, from Garden River First Nation, an Anishnaabe scholar at Mount Allison University.

- Kahente Horn-Miller, Kanien:keha'ka, Indigenous studies at Carleton.

- Mark Macdonald, Wendat, an Anglican archbishop who teaches at Wycliffe College.

- Martin Brokenleg, member of Rosebud Sioux first nation, formerly Director of Native Studies at Vancouver School of Theology.

- Jonathan Hamilton Diabo, Kanien:keha'ka, theologian at Emmanuel College, Toronto, United Chuch of Canada.

- Adam Murry, Chiricahua Apache, scholar in Indigenous psychology at the University if Calgary.

- Terry LeBlanc, Mi'kmaq / Acadian, director of NAIITS, an Indigenous learning community, with academic appointments at several Canadian theological schools.

- Carmen Lansdowne, Heiltsuk, a United Church of Canada minister and scholar of Christian theologies of mission, who teaches at the Vancouver School of Theology.

- Tasha Beeds, a doctoral student at Trent University whose master's degree research focused on the Ven. Edward Ahenakew (1885–1961), a Cree Anglican priest and scholar.

- Chantal Fiola of the University of Winnipeg has written Rekindling the Sacred Fire (2015), which discusses the Roman Catholic and Indigenous influences in Métis religions.

Click to go to Page 6: Settler Colonialism