Acknowledging my perspective

My point of view. The point of view from which I look at things, including historical things, is influenced by my social situation, emotional investments, and self-interest. This is an ancient and perhaps obvious wisdom, which in the twentieth century has been the subject of "the sociology of knowledge." Most people who consider "Indigenous and Settler Christianities in Canada" will come to our topic with a perspective on it that has been shaped by whether or not they are Canadian, whether or not they are Christian, and whether they are Indigenous or settler or bicultural. And of course each of these categories has its own distinctions, subcategories, contested definitions, and ambiguities.

As researchers have moved past the fiction of value-free, no-agenda objectivity, they have recognized the importance of acknowledging their own perspective in their writing. If we're aware of our perspective, and recognize that it is in fact a "perspective" that isn't universally shared, — that other people who look from a different vantage-point will see things that we can't see, — we can, perhaps, to some extent, recognize the limits of our knowledge and correct for them.

A settler point of view. My perspective is that of a settler Christian Canadian (or Canadian Christian settler or Christian settler Canadian, or whatever). On this page I'll focus on the "settler" part. I'm a participant in a settler colonial system and a beneficiary of it. I've been brought up in its ideological supports, including national settler narratives and Eurocentric academic studies. When I was raised in California, Junípero Serra (1713–1784), the Franciscan priest who was canonized in 2015 as "the apostle of California," was widely seen in heroic terms (except by those Protestants who never saw any Roman Catholics in heroic terms). Conversations about his impact on Indigenous cultures have emerged only recently.

A settler point of view. My perspective is that of a settler Christian Canadian (or Canadian Christian settler or Christian settler Canadian, or whatever). On this page I'll focus on the "settler" part. I'm a participant in a settler colonial system and a beneficiary of it. I've been brought up in its ideological supports, including national settler narratives and Eurocentric academic studies. When I was raised in California, Junípero Serra (1713–1784), the Franciscan priest who was canonized in 2015 as "the apostle of California," was widely seen in heroic terms (except by those Protestants who never saw any Roman Catholics in heroic terms). Conversations about his impact on Indigenous cultures have emerged only recently.

The perspectives and ideologies of settlers and colonizers are topics in the discipline of settler colonial studies. This discipline has helped me think about my perspective and its limitations.

What is settler colonialism?

Colonialism in general. The general category "colonialism" means the political and economic domination of a territory and its inhabitants by other people from another territory. Colonialism operates with an imbalance of power favouring the colonizers over the colonized. Different kinds of colonialism can be distinguished, but let's reduce them to two: franchise colonialism and  settler colonialism. In both, a colonizing power invades a new territory and maintains its ascendancy in the colony from the far-away "metropolis" through its military, its goverinng officials and civil servants, its traders and commercial agents, its teachers and missionaries, and other personnel. But they can be distinguished in the following way:

settler colonialism. In both, a colonizing power invades a new territory and maintains its ascendancy in the colony from the far-away "metropolis" through its military, its goverinng officials and civil servants, its traders and commercial agents, its teachers and missionaries, and other personnel. But they can be distinguished in the following way:

- Franchise colonialism: the metropolis is mainly interested in the resources and native labour of the colony. Its agents spend a tour of duty in the colony, and sooner or later go home (usually), to be replaced by other agents who will also go home. The colony remains subordinate to the metropolis and serves its interests. An example of franchise colonialism is "the scramble for Africa" in the nineteenth century, where various European powers set up colonies in different parts of Africa. Not many of the white colonizers wound up settling permanently in Africa. The invaders didn't to move the Africans out of the way of colonial settlement.

- Settler colonialism: the metropolis is more interested in the land of the colony than in the native labour. The colonizers therefore aim to displace the original inhabitants by geographical relocation, individual removals, assimilation, or homicide. The colonizers don't go home, but come to stay. They create their own nation-state, which requires them to displace the nations that were there before. The colony separates from the metropolis. Examples of settler British colonies are those that became merged into the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Historically the two types of colonialism have usually overlapped at first. For instance, when French adventurers came to Canada in the seventeenth century, some came to stay, and others didn't. And the ones who did come to stay likely didn't envision displacing the original inhabitants, who hugely outnumbered them, and whose help they needed for their commecial activity (especially the fur trade), ecological knowledge, and military alliances.

"Invasion is a structure not an event"

A basic principle of settler colonialism. Writers in the aera of settler colonial studies (discussed below) have proposed that a principle of fundamental importance for settler colonial states is that their colonialism is a structure not an event. That means that it's still around.

This idea can come as a surprise, since most of us settlers in Canada situate the period of colonialism, invasion, and Indigenous displacement in the distant past, mainly in the first generation or two following initial European–Indigenous contact, or a bit longer. We probably acknowledge that many unfortunate things happened in that distant past, when we weren't around — and we don't have responsibility for any of that, we feel. And now it's all "water under the bridge;" the passage of time has normalized things.

The period of Indigenous displacement has not finished. To say that invasion is a structure, not an event, is to say that the goal of Indigenous  displacement and elimination persists in the settler state — in fact, not only does it persist, but it also shapes and structures our political, economic, social, and constitutional institutions and discourse.

displacement and elimination persists in the settler state — in fact, not only does it persist, but it also shapes and structures our political, economic, social, and constitutional institutions and discourse.

Some examples. And if we look, it's not difficult to think of examples in Canada. We have disputes about the settler exploitation of natural resources on (or across) Indigenous territory — a worldwide phenomenon, as this United Nations report discusses. We have court decisions that define and restrict Aboriginal rights. Dozens of land claims negotations are in process acrsos Canada which will partly affirm and docoument Aboriginal territorial rights but will also protect the federal government's ultimate right to seize treaty lands. It has become clear that police and publics have been slow to probe reasons for the pattern of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls, in numbers that would not go so long unnoticed for settler women and girls. Indigenous children are taken away from their homes by child services personnel who might have made different decisions with settler children, as documented, for instance, by the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Settler colonialism and Canadian identity. In fact, settler colonialism may not just be one characteristic of Canada among others. Writers in settler colonial studies claim that it structures Canada more fundamentally than any other divisions, whether class, race and ethnicity, gender, or francophone/anglophone biculturalism. They acknowledge that these other divisions are very real, and that they overlap with settler colonialism, but they affirm that settler colonialism is distinctively at the root of our Canadian identity.

Ideology

Settler states justify their structures of settler colonialism ideologically. They don't necessarily justify past outrages. For instance, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for the harm done by Indian residential schools. The apology was warmly welcomed. But Mr. Harper seemed to interpret the schools as an aberration, and not part of a history of colonialism, which he didn't recognize that Canada had. We can also see a pattern of "moves to settler innocence." One way of moving to innocence, as I've already noted, is by assigning settler injustice to a remote past. Another is by simply removing Indigenous peoples from settler view, as in the school textbooks of Canadian history that begin with a chapter on Indigenous peoples and then "disappear" them. Another is through narratives of settler sympathy, generosity, and philanthropic feeling towards Indigenous peoples, not lingering on the patterns of Indigenous displacement and exclusion that invited settler philanthropy. There are also harsher, blame-the-victim approaches where Indigenous peoples are presented as aimlessly nursing resentments over past wrongs, or refusing to move on with their lives, or refusing to appreciate that they should accept assimilation into the dominant society.

Those of us who are settlers, socialized into settler colonial states, have been deeply influenced by ideologically shaped assumptions and perspectives.

A personal example

Here's one of many cases where my filters clouded my historical judgment. In 1998 I was part of a group that collaborated on a history of St. James Anglican Cathedral in Toronto. When we talked about how it received its site in 1797 we gave no hint as to how it obtained its land at the expense of the people who were already there. We wrote about settler realities: the Canada Act of the British Parliament in 1791, and about how Lieutenant Governor Simcoe turned the military camp at Toronto harbour into a government town, and about how his administrator extended the townsite, and about how the clergy were appointed. We said that the first Anglican minister left after a few months in part because of the "threat of attack by the Mississaugas," but it didn't occur to us to say why the Mississaugas might want to attack. (And the term "Mississaugas" didn't make it into the index; the point was too unimportant.) We also didn't talk about how John Strachan, the rector of St. James from 1812 to 1847, took a leading role in the dispossession of Indigenous lands, and his involvement in the lucrative colnoial occupation of land speculation; nor about his deep involvement in missions to First Nations peoples. Indigenous realities had figured strongly in the experience of this settler parish, its clergy, and people, but we told the story almost as if Indigenous peoples weren't around.

The origins of settler colonial studies

The origins of an academic field of study. The term "settler colonialism" appears to have first been used in the 1920s, but it wasn't until the 1990s that it began to name a field of study. A number of scholars at that time were seeing that the settler state was distinctive and important as a global phenomenon in ways that invited specialized study. A significant reason for this developing scholarly interest was the new prominence of the tensions, protests, problems, and sometimes violence in the relationship of Indigenous and settler peoples, for a generation of Indigenous activism had burst forth in 1967 in Canada, the USA, and Australia. Settler responses pointed to underlying, previously unnoticed (or underestimated) social and cultural structures of settler thought, economics, politics, and law. These now seemed to deserve study. This is an interdisciplinary field that involves anthropologists, historians, economists, political scientists, sociologists, scholars of literatures, and others, both settler and Indigenous.

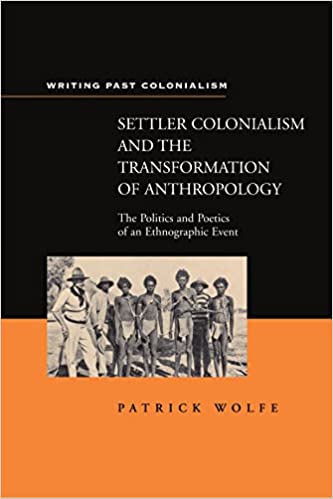

Patrick Wolfe's Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology (1998) is usually identified as the seminal book of the discipline. Wolfe (1949–2016), originally from Yorkshire but an Australian by choice, he earned his PhD at the University of Melbourne with the thesis that he later adapted into this influential book. He never held a permanent teaching position, possibly because he was seen as something of a radical, but he did have teaching appointments in Australia at Melbourne, Victoria, and La Trobe, as well as fellowships at Harvard and Stanford, among other distinctions. In addition, he was an acclaimed public intellectual who lectured on numerous occasions around the world. He's remembered by students and colleagues as enthusiastic, intense, erudite, warm, giving, and passionate for social justice. He was a founder of the peer-reviewed academic journal Settler Colonial Studies, which began appearing in 2013 and is available on-line.

Patrick Wolfe's Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology (1998) is usually identified as the seminal book of the discipline. Wolfe (1949–2016), originally from Yorkshire but an Australian by choice, he earned his PhD at the University of Melbourne with the thesis that he later adapted into this influential book. He never held a permanent teaching position, possibly because he was seen as something of a radical, but he did have teaching appointments in Australia at Melbourne, Victoria, and La Trobe, as well as fellowships at Harvard and Stanford, among other distinctions. In addition, he was an acclaimed public intellectual who lectured on numerous occasions around the world. He's remembered by students and colleagues as enthusiastic, intense, erudite, warm, giving, and passionate for social justice. He was a founder of the peer-reviewed academic journal Settler Colonial Studies, which began appearing in 2013 and is available on-line.

Wolfe's book isn't an easy read, and for an introduction to the discipline people often go to Lorenzo Veracini's Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (2010). Veracini, who earned his PhD in 2002 at Griffith University in Queensland, is a professor of history and political science at the Institute for Social Research at Swinburne University of Technology, which has campuses in the state of Victoria, Australia.

Wolfe's book isn't an easy read, and for an introduction to the discipline people often go to Lorenzo Veracini's Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (2010). Veracini, who earned his PhD in 2002 at Griffith University in Queensland, is a professor of history and political science at the Institute for Social Research at Swinburne University of Technology, which has campuses in the state of Victoria, Australia.

Departments, research clusters, and other units of settler colonial studies have emerged at several universities, such as the University of Ottawa, and a remarkable number of articles and books have been published in the area

Wolfe's book

Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology probes the relation between the Australian settler state and the publications of key anthropologists mainly about Australian Aborigines between the 1850s and 1950s. It has a final chapter on political developments in Australia since then. Its thesis is that settler colonialism and anthropology have been ideologically entangled. He isn't writing about personal entanglements, although, indeed, sometimes anthropologists served as advisers to settler governments. But it's not that anthropologists deliberately set out with the intention of supporting colonialism. Instead, Wolfe is arguing that their methods and rhetoric hid ideological commitments that made ready connections with the ideology of the settler  colonial state. As a result, governments for their own purposes could appropriate useful ideas from the anthropologists, even though in some cases they lifted these ideas out of context or misinterpreted them.

colonial state. As a result, governments for their own purposes could appropriate useful ideas from the anthropologists, even though in some cases they lifted these ideas out of context or misinterpreted them.

Most of the book is a history and analysis of some key anthropological ideas. This analysis can become pretty technical, and non-anthropologist readers will sometimes feel a bit lost in his terminology and explanations. I don't know that many would have been predicted that this narrowly focused, closely argued, thickly cited, densely written book would wind up having such a powerful impact. In fact, at first it didn't. It gradually gained traction. I suspect that its influence has less to do with its erudite discussions of anthropology than with its discussions of the history and character of settler colonialism, and that our western academic research is ideologically freighted.

Wolfe sees two main phases in the anthropology of this period (1850s–1950s).

- In its first phase, it served a narrative of social evolution. The anthropologists believed that all human societies evolved through a number of predetermined phases from primitive to advanced. Thus, by looking at Aborigines in their own day, they could understand the early beginnings of their own European peoples. In other words, their project was a narcissistic one; they wanted to study "their" now in order to appreciate "our" past. The narrative of social evolution determined their method, which was to begin with the earliest residues they could find of European culture — especially mythology — in order to predict what they would find among the Aborigines. And, knowing what they were supposed to find, they found it. In other words, their anthropology, although it gave the appearance of empirical, data-driven resesarch, was actually a "projection onto Aborigines of European fantasies about Europe's own prehistory" (p. 22). Social evolutionism finally collapsed under the weight of its internal contradictions.

- In its second phase, anthropology in Australia abandoned the narrative of evolution, and indeed cast aside all narrative, and analyzed each Aboriginal group from an orientation of cultural relativism, as if each group were a social isolate, frozen in time, outside history. This was the approach of "structural functionalism," which held sway in anthropological circles for a period beginning in 1922. Structural functionalists analyzed a society as a complex system of various structures which function together to promote shared values and social stability. How social change happens was not its concern. By preference, the anthropologists sought to construct "pure" Indigenous societies before their contamination by European contact. Of course, in the real world, actual societies experience historical change. So the structural functionalists were constructing essentialized Aboriginal cultures that no longer existed, and perhaps never did.

Thus the anthropologists misread Australian Aboriginal cultures in the period that Wolfe is considering. Although they did indeed spend time with Aborigines in Australia and talked to them, Wolfe contends that "there is little if any evidence of these dialogues having had any impact on anthropological theory" (p. 4). Wolfe doesn't test the anthropologists' conclusions against the data: others have done that, such as Lester Hiatt. Instead, he treats their arguments as sets of closed, logically structured, dialectical, rather claustrophobic discussions that sometimes could feel like soliloquies. And when the writers sensed vulnerabilities in their arguments, or were confronted with counter-evidence in their data, they defended their main conclusions with rhetorical subterfuge and supplementary theorizing.

Their main theories involved kinship and property (blood and soil), which in turn organized their discussions of more specific topics such as animism, totemism, mother-right (matrilineal descent), and nescience (meaning either an ignorance that pregnancy depends on intercourse, or an ignorance of which men fathered which children). Wolfe leaves it doubtful that what the anthropologists had to say about any of these topics was accurate. In fact, he calls totemism "the purest of theoretical inventions" (p. 105).

These two phases of anthropology correspond to two phases of Australian settler colonialism.

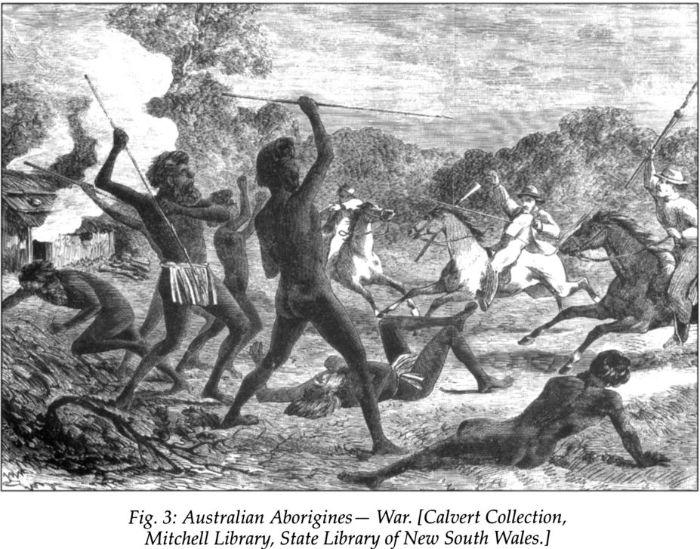

- First, Australian settlers expanded territorially and dispossessed Aborigines of their land. Anthropological theory provided a justification for territorial dispossession by presenting Aborigines as primitive peoples, in fact the most primitive people in the entire

world. It posited a binary between "us" and "them" that justified establishing frontiers between the two "types." And it explained that Aborigines were too primitive to understand property in the correct, advanced, British sort of way; "land had to become property for rights of ownership tro be applied to it" (p. 26). Accordingly, settlers felt they had every right to move Aborigines off their land (since it wasn't really "their" land), often by homicide. During this period, settlers were constantly pushing the "frontier" further out, and constraining Aborigines within ever narrower boundaries.

world. It posited a binary between "us" and "them" that justified establishing frontiers between the two "types." And it explained that Aborigines were too primitive to understand property in the correct, advanced, British sort of way; "land had to become property for rights of ownership tro be applied to it" (p. 26). Accordingly, settlers felt they had every right to move Aborigines off their land (since it wasn't really "their" land), often by homicide. During this period, settlers were constantly pushing the "frontier" further out, and constraining Aborigines within ever narrower boundaries. - In the second phase, Aborigines were inside settler territory, but were required to be not visible. In settler colonialism, "the Aborigine is always somewhere else" (p. 173). That could no longer mean "beyond the frontier," as it did in the first phase, because settler Australia was now an independent nation-state that claimed the entire continent. So Aborigines had to be within national boundaries, but it was still necessary to keep them separate from settlers. At this point, settlers had two alternatives:

- Keep Aborigines on reserves. The structural functionalists represented Aboriginal groups as self-generating, isolated communities, and therefore external to the settler economy. They were not dependent on settler society, and would not be transformed by it. They simply needed to be kept out of the way, in their own space, "not conflicting with the practical exigencies of settlement" (p. 179).

- Assimilate Aborigines. The structural functionalists helped here, as well, by defining "authentic" Aborigines as those conforming to the anthropological constructions of a pure, essentialized, pre-contact culture. If the Aborigines came off their reserves and began engaging with settler society, they were no longer authentic. Wolfe calls settler practice in this regard "repressive authenticity." Settler laws made it easy to disqualify hybridized Aborigines from being considered real Aborigines: they therefore became non-Aborigines — although socially they remained identifiable as "the other," and were often lampooned by settlers as domesticated savages who drank and fought among themselves in urban alleyways.

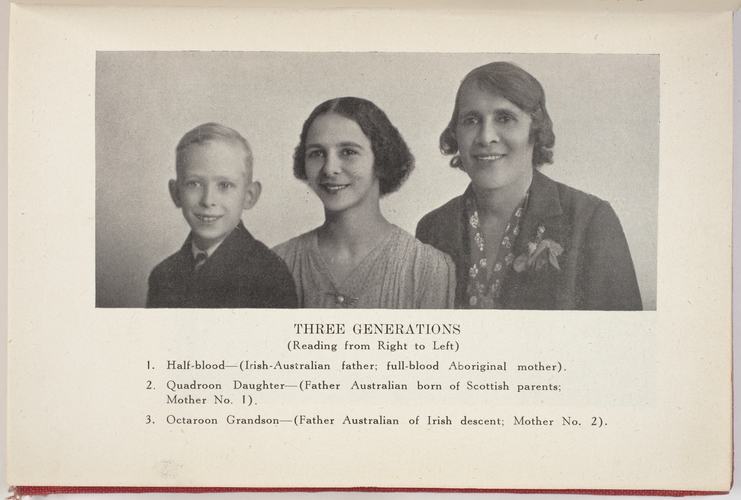

"Half-castes" remained a "problem." Wolfe observes, "The chronic negator of the logic  of elimination had been the white man's libido" (p. 181). Half-castes complicated the policy of genocide, and turned attention from the "dying Aborigine" to the "half-caste menace." Notoriously, Australia developed the policy of taking half-caste children away from Aboriginal families and adopting them out to white families: this policy created the "stolen generations". The half-caste children, when they grew up, were expected to marry white partners, and the third generation would look white themselves. (Wolfe includes this picture of the "whitening" over three generations from a 1947 book by A.O. Neville, the settler "Chief Protector of the Aborigines.")

of elimination had been the white man's libido" (p. 181). Half-castes complicated the policy of genocide, and turned attention from the "dying Aborigine" to the "half-caste menace." Notoriously, Australia developed the policy of taking half-caste children away from Aboriginal families and adopting them out to white families: this policy created the "stolen generations". The half-caste children, when they grew up, were expected to marry white partners, and the third generation would look white themselves. (Wolfe includes this picture of the "whitening" over three generations from a 1947 book by A.O. Neville, the settler "Chief Protector of the Aborigines.")

In 2013 Prime Minister Julia Gillard apologized for the forced adoptions. The movie "Rabbit-Proof Fence" is loosely based on a true story of young women in "the stolen generation," and the movie "The Sapphires" includes a "stolen" character.

Settler colonialism is motivated by greed for land (p. 27), but doesn't like to admit it. The greed requires the social elimination of the original inhabitants. Although the essential distinction between Indigenous and settler is "the relation of invasion" (p. 188), settlers divert attention from the invasion by constructing Indigenous and settler as types in polar opposition. Anthropology, as we have seen, helps with that. In order to legitimate themselves, settlers construct ideologies to rationalize and legitimate their greed and the dispossession of other peoples. Anthropology helps with that, too. The ideologies don't themselves generate settler colonialism; they justify it.

Narratives of settler nationhood function romanticize the past. When settler Australia became a nation-state, it needed narratives of legitimation that excluded the illegitimate realities of settler homicide and land theft (p. 33). That might have meant writing Aborigines out of the story altogether. Bu ton the other hand, Australia valued its Aboriginal peoples for contributing a romantic element to its national identity. As an example, Wolfe notes the Australian $2 coin that pictures an Aborigine, and a Waripiri design of serpents converging on a waterhole that is incorporated into the Parliament buildings in Canberra. (After his book was published, Australia showcased Aboriginal cultures when it hosted the Olympic games in 2000.)

Christianity figures in the book in various ways.

- Anthropology repudiates religious explanations. Like other nineteenth-century academic disciplines, such as history, geology, biology, and even critical Biblical studies, anthropology looked for explanations that could be verified from empirical evidence and observable data, rather than inferred from theological principles that could be acknowledged only by people of faith. The anthropological project was "deriving consciousness from mundale social conditions" that could be observable.

- As a result, anthropologists disparaged Aboriginal spirituality and religion. They didn't give credit to what Aborigines believed "metaphysically." Since the evolutionary anthropologists commonly thought that peoples move from magical thinking to religious thinking to scientific thinking, they were unwilling to believe that the Arranda people of Australia were capable of transcendence or "any suggestion of religious sentiment" (p. 126). They therefore misunderstood their spirituality. They explained it on the basis of their favoured category of kinship, by way of a theory of totemism.

- The Christian missionaries often did better. Wolfe expresses appreciation for Carl Strehlow, a Lutheran missionary west of Alice Springs. Where professional missionaries took photographs that posed the Arranda people in order to display their "uncontaminated savagery" (p. 154), Strehlow photographs showed them more realistically. The anthropologists descended on the Aborigines for short periods with interpreters in tow, and often relied on one or two preferred informants, whereas missionaries learned Indigenous languages, lived in the communities for many years, participated in their social life (though not their religious ceremonies), and recognized their complexity. But since missionaries weren't part of the academic profession, the anthropologists didn't value their observations.

Go to: Page 7: First Contacts in Eastern Canada