This page surveys the Indigenous peoples who first made contact with Europeans in what's now Canada. The Europeans were mainly French, and the Indigenous peoples were mainly speakers of Iroquoian languages and Algonquian languages. This page serves as a preface to the story of Indigenous–settler Christianities in New France.

When was initial contact?

Initial contact between European peoples and Indigenous peoples in what's now Canada happened at different times. In general the time of contact was earliest in eastern Canada, and happened successively later from east to west to north.

- The Beothuks of what's now Newfoundland and Labrador probably met Vikings by 1100; they met English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese fisherfolk in the late 1400s.

- Iroquoian-speaking peoples and eastern Algonquian-speaking peoples began meeting the French after 1534. Regular trading contact increased in the 1590s. Sustained contact began in the early 1600s.

- Cree and other Prairie peoples began meeting French and English explorers and traders in the 1660s. These Europeans arrived via Hudson's Bay during the two or three weeks of the year when the voyage there was free of ice. The Hudson's Bay Company was formed in 1670.

- Indigenous peoples in what's now British Columbia began meeting Russians in the 1720s, and Spanish and British in the 1770s. European trading posts began to be established in the early 1800s. With the first gold rush in 1850, Europeans began to settle in large numbers.

- The Inuit had fleeting early contacts with Vikings and European explorers

and fisherfolk before the eighteenth century. The Inuit of Labrador first had sustained contact with Europeans in the 1770s, when Moravian missionaries came to them. For Inuit living in regions draining into the Arctic Ocean and its marginal seas, sustained contact with Euro-Canadians began about 1910

and fisherfolk before the eighteenth century. The Inuit of Labrador first had sustained contact with Europeans in the 1770s, when Moravian missionaries came to them. For Inuit living in regions draining into the Arctic Ocean and its marginal seas, sustained contact with Euro-Canadians began about 1910

Shock waves. The impact of Europeans preceded their physical arrival. Tomson Highway, the Cree playwright and author (pictured here), describes initial contact as a "shock wave" which distant peoples felt long before they met any Europeans in person. European technology (such as kettles and guns), ideas, trade opportunities, and epidemic diseases preceded personal encounters with the Europeans. But the shock waves exapanded differentially, affecting some distant peoples more than others. The result could be variable opportunities for trade and technology, variable threats from disease and prospective colonization, rivalries, and power imbalances.

Christianity often preceded Europeans. Time and again during this three-century process of gradual contact in Canada, as we'll observe in the following webpages, we find that Indigenous peoples learned about Christianity before any Europeans told them about it. Indigenous trade networks and kinship structures were communication channels for new and intriguing ideas, and for warnings of impending danger.

Sources

Western approaches to knowledge have privileged the principle verba volant scripta manent, "spoken words fly away but written words endure." (This idea obviously pre-dates the era of sound recordings. It also pre-dates post-modern criticism, which has subverted confidence in written evidence.) Westerners have been perplexed how to find dependable evidence for oral cultures. They (we) have commonly relied on the following sources.

Western approaches to knowledge have privileged the principle verba volant scripta manent, "spoken words fly away but written words endure." (This idea obviously pre-dates the era of sound recordings. It also pre-dates post-modern criticism, which has subverted confidence in written evidence.) Westerners have been perplexed how to find dependable evidence for oral cultures. They (we) have commonly relied on the following sources.

Settler ethnographic reports. "Ethnography" is the description of cultures. For westerners, a very important access to knowledge about Indigenous cultures before contact has been settlers' observations immediately after contact. On the east coast of Canada the best example is the 72 volumes of the Jesuit Relations beginning in the 1630s. The Jesuit missionaries lived among Indigenous peoples, spoke their languages, had conversations with them, and reported on their lifestyles and ideas. On the west coast of Canada and in the north the best example is the "salvage anthropology" produced by academically trained and properly certified scholars, most prominently Franz Boas beginning in the 1880s among the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples and also among the Inuit of Baffin Island. These observations and reports have been extremely valuable and useful, but there are quite a number of problems with them, notably the following:—

- The evidence deteriorates on contact. As soon as Europeans arrive, cultures change. (They were changing before contact, too, of course.)

- The questions that the ethnographers ask determine the kinds of answers they receive.

- In the case of early anthropologists in particular, the ethnographers don't know the native language. They therefore rely on informants who know English, who are thus already partially hybridized.

- In depending for their information on a relatively few informants, the ethnographers are insulated from alternative perspectives, knowledge, and understandings.

- One result is that the ethnographers will underestimate the complexity of the culture they're reporting on.

- Another result is that they open themselves to receiving misinformation, since for various reasons the informants sometimes mislead the ethnographers.

- Another result is that they learn nothing about the things that only certain elders and knowledge-keepers are allowed to talk about.

- The ethnographers look for patterns, and thus, again, they therefore underestimate the complexity of cultures, where anomalies, which are usually relatively hidden, are as important as patterns.

- The ethnographers make sense of things, for themselves and for their audiences, by interpreting their observations from the standpoint of their own culture. Looking for similarities and differences, analogies and disanalogies, can make the ethnographers' culture the stable point of reference.

The ethnographers commonly don't look for, or don't notice, or don't bother to report, things they're not interested in.

The ethnographers commonly don't look for, or don't notice, or don't bother to report, things they're not interested in. - Similarly, the ethnographers usually have a larger point they want to make or a theory they want to prove or a premise they want to confirm, and they interpret, organize, and present their data accordingly. For example, the seventeenth-century Jesuits are evidently selecting quotations from their informants. Franz Boas, in taking pictures, framed and posed his subjects in ways that would support his observations.

- Colonialism can induce Indigenous peoples to understand themselves through the lens of settler ethnography. For instance, on some occasions Indigenous communities have sought to reconstruct their pre-contact traditions by studying settler salvage anthropology.

Many of these problems can begin to be resolved when ethnography is conducted in a collaborative way, where folks from different cultures both engage one another candidly and question their own "positionality," without deference to anyone claiming superior knowledgeability.

Archeology is the recovery (generally by excavation) and analysis of material culture.  By precisely locating objects, archeologists believe they can reconstruct lifestyles and activities. Finding datable objects, such as distinctive patterns and technologies of pottery, can help them date everything in the same horizontal location. Archeology has been most successful at determining how things functioned and how life was structured at a particular time and place. It has been more challenged in other areas:

By precisely locating objects, archeologists believe they can reconstruct lifestyles and activities. Finding datable objects, such as distinctive patterns and technologies of pottery, can help them date everything in the same horizontal location. Archeology has been most successful at determining how things functioned and how life was structured at a particular time and place. It has been more challenged in other areas:

- Figuring out what people believed, felt, and communicated. If a crown is recovered, you can reasonably imagine that it was something worn, but whether it's a symbol of rank, or of office, or of ritual function, or of nothing at all is elusive. An archeological site that included large homes and small ones might point at social inequalities, but not at the origin, dynamics, or contemporary rationales of social inequality. Archeologists can sometimes identify sites used for religious purposes, and can sometimes even reconstruct what happened there, but have no way into the hearts and minds of the devout.

- Recognizing what was important in the natural environment. Archeologists focus on material culture, and thus have no way of identifying whether a cave, hill, or stream was important or even sacred.

- Identifying processes of social change. An archeological site is like a snapshot, which leaves open possibilities about how things came together in the way they did. However, external influences on social change can often be surmised, such as environmental change and cross-cultural contact.

Since the 1960s a subfield of ethnoarcheology has sought to address some of these problems, by seek the symbolic significance and social meaning of material culture. However, its success in doing so has been questioned. For instance, one of its approaches has been "analogical inference," that is, seeing how things are used in a living culture as a way of imagining how they were used in a historic culture. But not every agrees on how far we can see common patterns in different cultures. Somewhat distinguishable from ethnoarcheology in general is Indigenous archeology, which seeks to use archeology for Indigenous empowerment and justice, and incorporates Indigenous oral tradition into its methodology.

Drawing and painting. Interpreting the images left by an oral culture overlaps with archeology, and is sometimes claimed by it as its rightful domain, but I think it deserves its own mention. Among Indigenous peoples in eastern Canada, petroglyphs or rock art are particularly noteworthy. Petroglyphs Provincial Park in Ontario has about 1200 carvings, about a thousand years old. Agawa Rock in Lake Superior Provincial Park is also widely known. In eastern Canada, Iroquoian pots (such as the  small one shown here from the Canadian Museum of History, very likely pre-contact) and pipe bowls and stems may have geometrical designs and animal and human iconography. On Webpage #8 we'll note the pictographs by which representatives of Indigenous groupings validated treaties in New France; although these obviously date from the colonial period, one can imagine that similar drawings were made on less permanent surfaces before paper was available.

small one shown here from the Canadian Museum of History, very likely pre-contact) and pipe bowls and stems may have geometrical designs and animal and human iconography. On Webpage #8 we'll note the pictographs by which representatives of Indigenous groupings validated treaties in New France; although these obviously date from the colonial period, one can imagine that similar drawings were made on less permanent surfaces before paper was available.

Historical linguistics can be a tool of ethnohistory, when it's used cautiously. Language is a product of culture that expresses and reinforces worldviews. Words can tell us about the foods people ate, the technologies they used, the social structures that they inhabited, and the spirits that they recognized. Linguistic families and loanwords can point to historical relationships among peoples.

Oral traditions and stories. Indigenous stories about the past mobilize community memories. They are regularly recounted in families and presented in community performances of story-telling. In various ways, depending on the social structures of the communities involved, they are corrected or verified by knowledge-keepers and elders. As part of their colonialist ideology, settlers have tended to denigrate Indigenous stories as primitive artifacts, vitiated by superstition. Christians are perhaps in a position to recognize the value of oral tradition, since the gospel accounts of Jesus, and many other parts of the Bible, are clearly reliant on oral tradition. It's recognized that people in oral cultures are far better at holding things in individual and collective memory than people in literature cultures, because they have to.

Ethical issues. When settlers research and write about Indigenous peoples as "the other," tremendous ethical issues arise. Settler ethnographic accounts, colonialist and Eurocentric in their origins, inevitably confirm colonialist and Eurocentric perspectives. Archeologists in the past have too often planned research without concern for its impact on Indigenous peoples, disrupted communities, revealed secrets, misrepresented realities, profaned sacred places, and reinforced colonialism. Indigenous story-telling has too often been captured, transcribed into a quasi-canonical written form, decontextualized, objectified, analyzed in western terms, and appropriated.

Conflicts in evidence. Western scholars have often presumed to adjudicate conflicts in evidence, most typically conflicts between the colonial documentary record and Indigenous oral tradition. In recent decades Canadian courts of law have been obliged to do the same. Here are a couple of examples.

- In Haudenosaunee tradition, in about 1613 a Dutch trader asked the Mohawks for permission to build a trading post on Castle Island in the Hudson River. The two parties reached an agreement confirmed by a two-row belt of purple and white wampum, representing the two peoples navigating a river side-by-side without interfering with each other. ("Wampum," from a southern Algonquian word wampumpeague, means " shells," and refers to white and purple beads fashioned from whelk, and from clam or quahog shells.) The wampum agreement is called a kaswentha (pronounced closer to "guswenta"). A number of critical western scholars, finding no documentary evidence of the agreement, and no other example of a wampum belt at that date, decided that the story was a nineteenth-century fiction. The issue became heated as 2013 drew near, since some groups in New York wanted to celebrate the anniversary of this historic peaceful and respectful agreement between nations. As it happens, in this case vigilant western scholars did find seventeenth-century documentary references to the agreement as well as evidence of purple and white

beads at a sixteenth-century Mohawk archeological site.

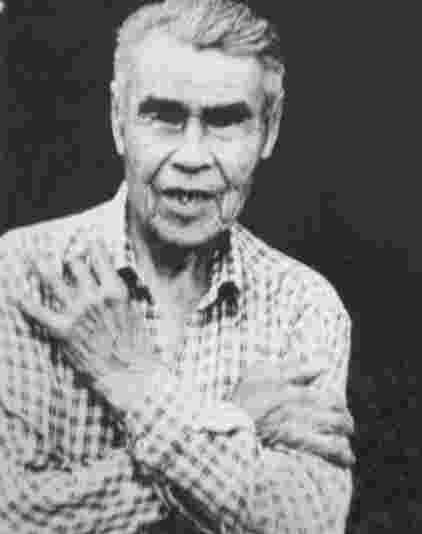

beads at a sixteenth-century Mohawk archeological site. - In 1984, in order to stop clear-cut logging on their territory, Wet'suwet'en and Gitxsan leaders sued the province of British Columbia for recognition of their land claims. The case was named for the Gitxsan office of delgamuukw. (Pictured is Albert Tait, the delgamuukw when the case was launched.) Legally the case hinged on whether the two Indigenous nations could demonstrate Aboriginal land rights, and that in turn depended on the admissibility of their oral traditions. The trial court threw out their claim. But the case made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia in 1997,

Notwithstanding the challenges created by the use of oral histories as proof of historical facts, the laws of evidence must be adapted in order that this type of evidence can be accommodated and placed on an equal footing with the types of historical evidence that courts are familiar with, which largely consists of historical documents.

The Beothuk

The Beothuk lived in Newfoundland for centuries before European contact. They appear  to have lived in groups of self-sufficient extended families. To the left are some Beothuk carved bone objects now in the Newfoundland Museum. The Beothuk language is known only from later European word-lists; these include Algonquian words, but these may have been loan words. Vikings and other Europeans may have met them a thousand years ago, but in the late 1400s European ships began coming in much greater numbers every summer. English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese fisherfolk had discovered the vast cod stocks of Newfoundland, both on the Grand Banks and inshore. By the late 1500s a thousand French boats a year were fishing Newfoundland cod, and sometimes entering the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Documentary evidence for contact between the French and Beothuk in these early years is sparse and unreliable; and archaeological evidence, such as iron nails in Beothuk arrowheads, can't be dated. The historian Cornelius Jaenen speculated that the Beothuk did make contact with Europeans before 1500, and that they shared stories with Indigenous peoples on the mainland, since the latter seemed to anticipate the arrival of Europeans in 1534. The Beothuks were officially decreed extinct in 1829, but their tradition is that they eluded persecution by moving to the mainland.

to have lived in groups of self-sufficient extended families. To the left are some Beothuk carved bone objects now in the Newfoundland Museum. The Beothuk language is known only from later European word-lists; these include Algonquian words, but these may have been loan words. Vikings and other Europeans may have met them a thousand years ago, but in the late 1400s European ships began coming in much greater numbers every summer. English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese fisherfolk had discovered the vast cod stocks of Newfoundland, both on the Grand Banks and inshore. By the late 1500s a thousand French boats a year were fishing Newfoundland cod, and sometimes entering the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Documentary evidence for contact between the French and Beothuk in these early years is sparse and unreliable; and archaeological evidence, such as iron nails in Beothuk arrowheads, can't be dated. The historian Cornelius Jaenen speculated that the Beothuk did make contact with Europeans before 1500, and that they shared stories with Indigenous peoples on the mainland, since the latter seemed to anticipate the arrival of Europeans in 1534. The Beothuks were officially decreed extinct in 1829, but their tradition is that they eluded persecution by moving to the mainland.

Nations met by the French

Constructing national identities. The French colonizers of eastern Canada divided Indigenous peoples into nations based on where the peoples generally lived and what language they spoke, since that was the European way. In fact, the French commonly spoke of the Indigenous peoples they met as "nations," which wasn't a word in vocabularies of the peoples themselves. In these cultures, kinship groups were the critical mode of identification. As Heidi Bohaker of the University of Toronto has pointed out, when representatives validated important documents with the French, such as the Great Peace of Montreal in 1703, they used pictographs representing their kinship groups. (See Webpage #8 for some details.) Their sense of community identity was evidently grounded in the common relationship of their kinship group to other-than-human progenitors.

Languages. The areas that the French would come to call Canada and Acadie were home to Indigenous peoples of two general language groups, Algonquian and Iroquoian. Here following, organized into the two language groups, are the nations that the French met when (or soon after) they arrived. In most cases I've given the name by which these nations prefer to be known today, and then in parentheses I've given the names by which the French knew them. I've included an indication (using modern place names) of where the colonizers found these peoples located. I do this for the convenience of map-checking, but with misgivings since I'm layering the colonizers' map over the geographies of the First Peoples.

Algonquian

- Mi'kmaq, in areas along the Atlantic Coast, Gaspé, and Newfoundland. This is an alliance of Indigenous peoples living in Mi'kma'ki

- Etchemin, south and west of the Mi'kmaq; this people disappeared in the seventeenth century

- Wulstukwuik (Maliseet), along the Saint John River valley, the Gulf of Maine, western area of the Bay of Fundy

- Abenaki, in southern Quebec and northern New England

- Innu (Montagnais), Quebec City and northeast into the Saguenay

- Naskapi, northeast of the Innu

- Attikamegues, in the Mauricie (i.e., around the St-Maurice River of Quebec)

- Anishnaabe

- Algonquin, in the Ottawa Valley

- Council of Three Fires

- Ojibwe (Chippewa, Ojibway), including the groups later called the Mississauga and the Saulteaux: north and west of Ontario (and across the U.S. midwest)

- Potawatomi, western Michigan

- Odawa, the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island

- Nipissing, in a large area around Lake Nipissing and Lake Nipigon

- Oji-Cree, northeastern Ontario to Lake Manitoba

Iroquoian

- the Haudenosaunee (Five Nations; Iroquois) lived along a corridor — a 300-kilometre Longhouse — from the Mohawk River valley to the Genesee River ("Iroquoia"). They were a confederation of nations: proceeding from east to west, they were —

- Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk), around what's now Schenectady

- Onyota'a:ka (Oneida), Oneida County

- Onondaga, around Syracuse

- Gayogohó:no (Cayuga), Finger Lakes

- Onödowa’ga (Seneca), Genesee River valley

- Skaru'ren' (Tuscarora), another Iroquoian people, were admitted as a Sixth nation in 1721, and lived in Oneida territory.

- The "St. Lawrence Iroquois" (a name invented by historian Bruce Trigger)

- Hochelagans, on or near Mount Royal in Montreal (the site is unknown)

- Stadaconans, at Quebec

- Erie, south shore of Lake Erie

- Wendat (Huron), Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay ("Huronia")

- Tionontati (Petuns, or Tobacco people), west of the Wendat

- Neutrals (includes the Chonnonton), in west of the Niagara River and in southwestern Ontario

In addition to the Iroquoian locations mentioned above, 1500 Iroquoian village sites have been found by archaeologists in southwestern Ontario and south central Ontario north of Lake Ontario, dating back at least as far as 500 C.E. (See the Warrick article referenced at left.)

Social organization

Generalizations about Indigenous ways of life shouldn't be trusted, because (as with Europeans) Indigenous Americans had a great variety of cultures. Moreover, their small communities often functioned fairly autonomously. Nevertheless, here are some generalizations that are widely agreed for the Algonquian and Iroquoian speakers of eastern Canada.

Residence. The Iroquoian groups were regarded as "sedentary" in that they had farms, where they were known for growing the "three sisters" of beans, corn, and squash. The Algonquian groups were generally called "nomadic" or "semi-nomadic" as hunter-gatherers; typically we think of them as living in easily disassembled birchbark wigwams. Ethnohistorians doubt that "nomadic" is an accurate general description of them. They argue that hunting didn't involve random wandering but was guided by family and kinship territorialities. Even apart from that, the distinction between Iroquoian and Algonquian isn't tidy. Iroquoian groups also hunted and gathered, and the Algonquian groups, especially in the more southerly areas, often established farms and settlements.

Government. Among Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples, hierarchy was unknown. The lack of a central coercive agency in their communities was one of the principal reasons why European colonizers thought that they were primitive. However, decison-making processes were actually well developed and complex. They depended on persuasion, consultation, and cooperation.

Clans. The Algonquian-speaking peoples generally had patrilineal clans, while Iroquoian clans were matrilineal. People weren't (aren't) allowed to marry within their clans.

Community independence. Each community had its own traditions, stories, and language dialect, and its own ways of governing and administering. As in every society, these ways changed and adapted over time according to circumstances and leadership.

War and peace. There were sometimes hostilities between groups, as recalled in the stories and oral traditions of the peoples, and as reflected sometimes in archaeological remains. For instance, the Iroquoian village at Hochelaga, according to Cartier, who visited there in theh 1530s, was triple-palisaded. There were also times for peace negotiations and alliances, also recalled in oral traditions.

Relations between nations

Communities also had complex relations with other First Nations, involving trade networks, intermarriage, and ceremonies.

Dish with one spoon. For hundreds of years Indigenous peoples in the general area of the St. Lawrence River basin had been negotiating agreements to share land and resources. Their treaties sometimes were represented as a single dish (symbolizing the land) and a single spoon (symbolizing the sharing), with no knife. The most famous of these agreements was the one connected with Deganawida, "the Great Peacemaker," and his follower Aiionwatha ("Hiawatha"), which brought the Five Nations or Haudenosaunee into confederacy long before European contact. Perhaps the second most famous example in this part of the world was the treaty between the Haudenosaunee and Mississauga in 1701. The ceremonies of agreement involved the exchange of belts of wampum (shell beads from quahogs or hard-shelled clams of the North Atlantic; these beads were obtained through trading networks from Indigenous peoples on the coast). The wampum belt was the form of the treaty.

A dish with one spoon wampum between Haudenosaunee and Anishnaabe peoples, probably from before contact, is in the possession of the Royal Ontario Museu m in Toronto. (Pictured: a reproduction of a dish with one spoon wampum belt, made by Richard Hamell of New York and posted on his Facebook page.)

m in Toronto. (Pictured: a reproduction of a dish with one spoon wampum belt, made by Richard Hamell of New York and posted on his Facebook page.)

Spirituality

The manitou among Algonquian speaking peoples (the word underlies the geographical names Manitoulin Island and Manitoba) is a spirit or life force or other-than-human person, found all around, in people and animals and the apparently inanimate environment, who could protect and help us, or obstruct and hurt us. The orenda among Iroquoian speakers is similar. (The picture shows an Ojibwe rock carving at Petroglyphs Provincial Park in Peterborough, Ontario. It's perhaps a thousand years old, and seems to represent a sun spirit.

Ceremonies can variously include prayers, songs, dances, smudging, offering, medicines, and rituals. (Here the Haudenosaunee Confederacy discusses its thirteen annual ceremonies today.)

Go to: Page 8: Christianities in colonial New France