Where and when was New France?

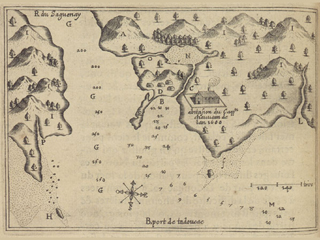

New France (Nouvelle-France) refers to France's zone of influence within North America,  where the European explorers, traders, missionaries, and settlers were predominantly French. Its pre-history can be said to begin with its chief early explorer, Jacques Cartier, in 1534. The first permanent French presence was a trading post established in 1600 on Innu land at Tadoussac (see Champlain's 1608 map of the port of Tadoussac at the left). New France ended when France relinquished any claims to the territory in the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

where the European explorers, traders, missionaries, and settlers were predominantly French. Its pre-history can be said to begin with its chief early explorer, Jacques Cartier, in 1534. The first permanent French presence was a trading post established in 1600 on Innu land at Tadoussac (see Champlain's 1608 map of the port of Tadoussac at the left). New France ended when France relinquished any claims to the territory in the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

"Age of Discovery." New France was thus founded during the period often called the "Age of Discovery," which extended from 1492 to the early 1600s. During this period, American and European peoples were making initial contacts with each other. The European peoples involved were mainly the nations along Europe's Atlantic coast (Spain, Portugal, France, Netherlands, England, Scotland). These European countries were carving out their respective zones of influence in the so-called "New World." This was a lengthy, complicated, messy, and often violent process. Violence was commonly a result when Indigenous nations and European nations sucked one another into military alliances against other alliances.

The fictions of "New France." On the map to the right New France looks huge; it's presented as a sprawling blue bloc extending from Newfoundland to the Gulf of Mexico. But the map is extremely deceptive. France didn't control this huge area either in fact or in law. The total French population over all this territory probably never reached even 75,000, most of it in the St. Lawrence River valley. Indigenous populations were much greater. The Indigenous nations in this territory all had well developed, networked social, political, and economic systems. Accordingly, on the ground, New France was more a notion than a cohesive political state. It comprised numerous settlements (ranging from small to tiny), forts, missions, farms, trading posts, and a great many geographically shifting, loosely linked nodes of influence.

Canada and Acadia. The most developed colonies in New France were both in what's now Canada. One of the colonies was called Canada (its settlements and farms were located within today's Quebec) and Acadia (Acadie) (within today's Maritime provinces, sprawling into Maine).

The sixteenth century

Indigenous peoples. See webpage #7 for an overview of what's now eastern Canada before the Europeans came.

Early French explorers. In 1534 the king of France commissioned Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), a mariner from  Brittany (which had recently been joined to France), on a voyage of exploration for gold, silver, copper, and spices, and a trade route to China.

Brittany (which had recently been joined to France), on a voyage of exploration for gold, silver, copper, and spices, and a trade route to China.

This initiative came several decades after Christopher Columbus' epoch-making voyage to the Caribbean in 1492. Spain was growing rich on its exploitation of "New Spain." France was envious.

Cartier found the St. Lawrence River. He planted a cross at Gaspé, and attempted to signify to the people he found there, perhaps Mi'kmaq, that they should look on it for their salvation. He sailed up to Stadacona (near the present Quebec City) and Hochelaga (the forerunner of Montreal) where he made contact with the Iroquoian-speaking peoples there. It was he who reportedly named Stadacona "Canada" from an Iroquoian word for "settlement." Iin time, the word "Canada" would come to denote increasingly larger territories. Cartier returned on two subsequent voyages. The results of these efforts were disappointing: he discovered no mineral resources of value and no passage to China, and an attempt at French settlement failed. Moreover, Cartier and his crews discovered what a Quebec winter was like. Europeans showed little further interest in exploring or colonizing this area before 1600.

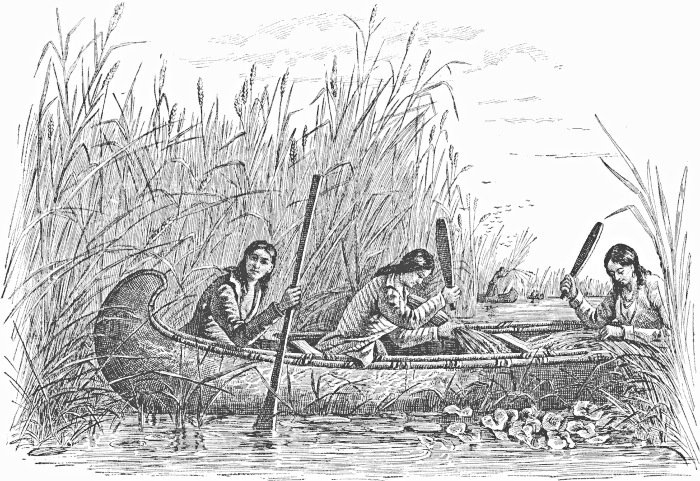

The fur trade. Although no settlers or colonizers arrived from Europe for the next seventy years, there were many contacts between Europeans and Americans. In particular, sometimes the French boats fishing Newfoundland took a detour into the St. Lawrence River and traded for fur with Innu peoples. In the 1580s, as wide-brimmed fur hats became fashionable on the Paris market, the demand for fur grew. Merchants from the French port town of St-Malo and  environs began trading for fur for its own sake, not just as a supplement to fish. They prospered richly. The fur trade gained traction and flourished.

environs began trading for fur for its own sake, not just as a supplement to fish. They prospered richly. The fur trade gained traction and flourished.

Crosses. Cartier planted several crosses in Canadian soil. Later writers sometimes interpreted these crosses as symbols of an intention to take possession of the land, although contemporary documents take them as navigational aids visible from the ocean, and as devotional objects for the sailors.

European reflections on the Americans. Europeans brought back from America stories and ideas, material objects (precious metals, furs, souvenirs), and diseases. These new things challenged European assumptions, puzzled people's minds, and expanded horizons. In addition, several Indigenous people were brought back temporarily to France (some had already been brought to Spain), voluntarily or otherwise. For instance, in 1602 the Innu sent a small contingent to France to observe its culture first-hand. They were received at the court of King Henri IV. Sometimes Indigenous folks were put on display at public events, reduced to servitude, or, if young, put into French schools. Because of difficult voyages and disease, many of them died there or en route.

Stereotyping. Peoples from such different cultures simply couldn't understand one another's mental universes and cultural worlds. And most didn't try very hard to understand, since almost invariably people assumed that their own culture, whichever it was, was the best one. So instead of serious investigation of other cultures and creative dialogue with "the Other," many French folks (and others too) began theorizing and generalizing about the Indigenous people of North America, based on biased reports and superficial observations. The most popular stereotypes were the following:

- Indigenous people were "noble savages" (to use a later term): they were wise about nature and simple in tastes; in their way of life in their world they resembled Adam and Eve in the lost earthly Paradise; they were untainted by the artificial social conventions endemic to Europe.

- They were wild, undisciplined, irrational, not fully human.

- They were just like Europeans in natural abilities and affections, but needed instruction to move up to European cultural standards.

The last stereotype would guide the missionaries of New France until the 1700s or later, when a fourth stereotype would emerge, the idea that Indigenous people were non-white, and racially inferior to whites.

Debates on Indigenous rights. When Spanish explorers and "conquistadores" in  America had sent news back home after 1492, they described Indigenous peoples as ignorant and primitive. They did so mainly because they didn't know any better, but also to justify their terrible treatment of them. That worked at first. Some credulous Spaniards, like Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, decided on the basis of these reports that Indigenous Americans weren't fully human beings. He explained that, according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, humanity came in a hierarchy of rational capacities, and Indigenous peoples were obviously (to him) in the lowest rung. They therefore had no natural rights and could legitimately be enslaved. Indeed, a number of colonial officials, military officers, and plantation owners eased their conscience about their treatment of Indigenous peoples by thinking of them as less than fully human — a tactic which has been used many times throughout human history. Other Spanish thinkers, however, thought differently, especially if they had actually met Indigenous peoples. One was Bartolomé de las Casas (c. 1484–1566), a Dominican missionary. He maintained that humanity was a unity, and he was one of the first people in history to advocate for universal human rights. Las Casas and Sepúlveda faced off in a debate in Valladolid, Spain, in 1550.

America had sent news back home after 1492, they described Indigenous peoples as ignorant and primitive. They did so mainly because they didn't know any better, but also to justify their terrible treatment of them. That worked at first. Some credulous Spaniards, like Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, decided on the basis of these reports that Indigenous Americans weren't fully human beings. He explained that, according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, humanity came in a hierarchy of rational capacities, and Indigenous peoples were obviously (to him) in the lowest rung. They therefore had no natural rights and could legitimately be enslaved. Indeed, a number of colonial officials, military officers, and plantation owners eased their conscience about their treatment of Indigenous peoples by thinking of them as less than fully human — a tactic which has been used many times throughout human history. Other Spanish thinkers, however, thought differently, especially if they had actually met Indigenous peoples. One was Bartolomé de las Casas (c. 1484–1566), a Dominican missionary. He maintained that humanity was a unity, and he was one of the first people in history to advocate for universal human rights. Las Casas and Sepúlveda faced off in a debate in Valladolid, Spain, in 1550.

A historic papal pronouncement. Even before the Valladolid debate, however, the pope had already pronounced in favour of Las Casas' position. In 1537 Pope Paul III promulgated the encyclical Sublimus Deus (the title is the first two words of the text). It affirmed that "Indians" were fully human beings, with souls and rational faculties. Even if they were heathen (non-Christian), the Pope said, they had natural rights to property and freedom. They could not legally be enslaved. (Popes, however, had little way to enforce the rules of the Church, and many Indigenous peoples were indeed enslaved, especially in New Spain.) The Church's position that Indigenous peoples are fully human was generally embraced by all missionaries to New France, and legitimated and reinforced their desire to save their souls.

Overview, 1600–1760

Some dates

- 1600: A permanent trading post is founded at Tadoussac by the Innu and French, This strategic location at the confluence of the Saguenay River with the St. Lawrence has long been a seasonal trading post in the territory of the Innu for people from many Indigenous American nations. It's the oldest settlement in which Europeans have been continuously resident in what's now Canada.

- 1603: Samuel de Champlain visits Tadoussac and meets Begourat, an Innu leader. The

Innu, trading partners with the French, are planning an attack on the Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawks). Champlain sympathizes with the Innu cause. For the next 150 years the Innu will ally with the French, whereas the Haudenosaunee will have long episodes of enmity with them. In fact, as a general pattern, the Algonquian speaking peoples in general will ally with the French against the Haudenosaunee; the latter will usually ally with the Dutch of New Netherland and their successors, the English of New York.

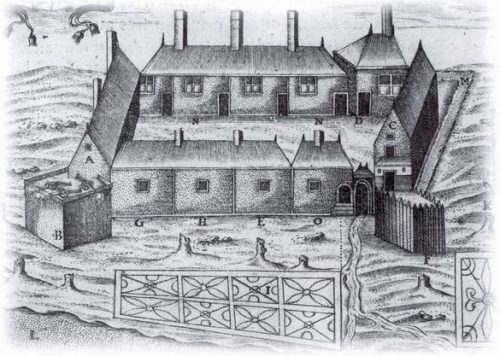

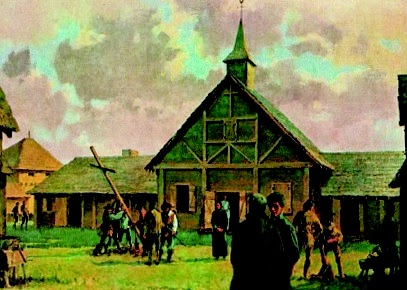

Innu, trading partners with the French, are planning an attack on the Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawks). Champlain sympathizes with the Innu cause. For the next 150 years the Innu will ally with the French, whereas the Haudenosaunee will have long episodes of enmity with them. In fact, as a general pattern, the Algonquian speaking peoples in general will ally with the French against the Haudenosaunee; the latter will usually ally with the Dutch of New Netherland and their successors, the English of New York. - 1605: Champlain helps establish the French settlement of Port-Royal (pictured right) on Mi'kmaq land (in what is now Nova Scotia). It's really just housing for a couple of dozen adventurers in the fur trade, but French settlers call it the capital of their colony of Acadia. (Descendants of the French settlers, intermarried with the Mi'kmaq, are called Acadians.)

- 1608: Champlain founds Quebec as a trading post for the fur trade. It's small at first. A couple of dozen French men overwinter under temporary contracts.

- 1609: The Wendat approach Champlain and the Innu about including them in a trade alliance which the Wendat had already established with the Algonquins. Champlain agrees.

- 1609: The agreement with the Wendat also involves Champlain in their war against the Haudenosaunee. Far to the south, perhaps in the area of what later became Fort Ticonderoga, Champlain and a mixed French and Indigenous group kill three Haudenosaunee. The event had long-term repercussions.

- 1610: In Port-Royal, Membertou, sakmow (grand chief) of the Mi'kmaq, and his wife, are baptized. He is reportedly 103 years of age.

- 1613: The first Port-Royal is destroyed by the English in 1613. A second Port-Royal is built eight klometres away. For the next century Acadia has a complicated history, with invasions from New England, at least nine major military clashes, unexpected changes in government, and overhauls of missionary arrangements.

- 1614: In France, Champlain founds a trading company with a royal

charter. It's predominantly Protestant in its personnel. (Later it merges with another company.) It serves as a French colonial government until 1627.

charter. It's predominantly Protestant in its personnel. (Later it merges with another company.) It serves as a French colonial government until 1627. - 1615: Champlain returns to Quebec with four priests of the Récollet order of Franciscans.

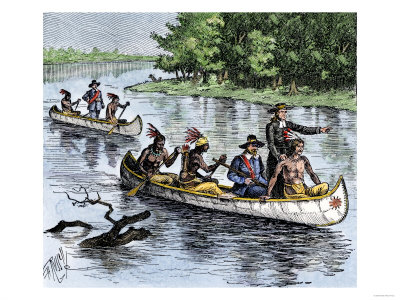

- 1615: Champlain winters with the Wendat. (In the image at right by C.J. Jefferys, 1925, a Wendat guide shows Georgian Bay to Champlain.) In 1619 he publishes an account of the experience.

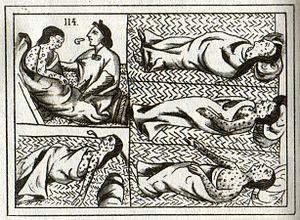

- 1616: Smallpox is reported at the colony's first fur-trading post, Tadoussac, among Innu and Algonquin peoples. From now into the 1630s smallpox will spread far and wide among the Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence areas. It's a killer. Alongo with other European diseases, smallpox reduces the Wendat population from perhaps 30,000 to 15,000.

- 1621: The king of England and Scotland issues a land grant in Acadia, formalizing conflict with France. The charter is in Latin, and New Scotland is called Nova Scotia.

- 1625: The first Jesuit priests arrive in New France.

- 1627: A new monopoly trading company is formed by Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister of France, replacing its failing predecessor as the governing authority of Canada. It's called "La Compagnie des Cent-Associés" (Hundred Associates). Its stated chief purpose is the conversion of the Indigenous population. Article XVII of the Act provides that all Christian Indians will have full rights of French citizenship.

- 1628: Richelieu establishes a system of land tenure called the seigneurial system, to regularize the colonists' landholding. (The legal relation of colonizers' lands to Indigenous lands is considered on another webpage.)

- 1629: English forces invade Quebec and occupy it until 1632. Missionaries are rounded up and sent back to Europe.

- 1632: Great Britain returns the Canadian colonial territory to France. Cardinal Richelieu grants the Jesuits a missionary monopoly in the Canada colony, and for Acadia he grants the Capuchin Franciscans a similar monopoly (quickly broken, however, by Récollets and Jesuits).

- 1634: Jesuits establish a mission community for Wendat peoples in an area called by the Wendat Wendake, and in English-language history books Huronia; it's an area around the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron. Measles begins to spread among Indigenous peoples in the region, killing large numbers.

- 1634: Trois-Rivières is founded. Algonquins, Innu, and Attikamegues are welcome there, as well as French, and it provides safety from Iroquoian attacks.

- 1637: Canada's first reserve is established at Sillery, near Quebec. The settlement, managed by Jesuits, becomes home to Algonquin and Innu Christian converts. Jesuits hope to assimilate them into French culture ("francisation"), but they fail. They begin to change their evangelistic strategy towards the accommodation of Indigenous traditions.

- 1639: Jesuits found the mission Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons.

- 1639: Ursulines, the oldest teaching order of women in the Roman Catholic Church, arrive in Canada. They take a particular interest in teaching Indigenous girls.

- 1639: Dutch settlers in what's now the Albany area trade in firearms with the Haudenosaunee. In 1641 New France decides that Christian "Indians" will be allowed to have firearms. (The French firearms, however, are inferior to the Dutch ones.)

- 1640: The Beaver Wars ("French and Iroquois Wars") begin, so called because they are triggered partly by competition for beaver fur. (Some date the beginning of the Beaver Wars to 1630, with a Haudenosaunee attack on Sillery.) The Haudenosaunee frequently raid the Indigenous trading allies of the French, take their furs, and sell them to the Dutch. There's much killing.

- 1649–1650: The Haudenosaunee, well armed and very skilled with flintlock muskets, destroy Wendat and Tionontati villages.

- 1657: The first Sulpician priests arrive in the colony, ending the Jesuit missionary monopoly. The order will undertake far-ranging mission work.

- 1663: La Compagnie de Cent-Associés, which has suffered as a result of the Beaver Wars, is ended. New France becomes a royal colony under the king's direct control.

- 1665: The first horses arrive in New France.

- 1666: The Beaver Wars take a pause with a tentative peace agreement. The Haudenosaunee in the Mohawk Valley (in what's now New York) allow Jesuit missionaries to live with them, as a condition of peace with the French.

1673: Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary to Indigenous peoples, along with Louis Jolliet, an explorer, and five French–Indigenous voyageurs, sail and portage from Green Bay down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Arkansas River. They meet Mascouten, Kickapoo, Fox, Kaskasia, and Miami peoples (some of whom already have European goods in their possession when they meet their first Europeans).

1673: Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary to Indigenous peoples, along with Louis Jolliet, an explorer, and five French–Indigenous voyageurs, sail and portage from Green Bay down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Arkansas River. They meet Mascouten, Kickapoo, Fox, Kaskasia, and Miami peoples (some of whom already have European goods in their possession when they meet their first Europeans). - 1675: the Wabanaki Confederacy (the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki, and Penobscot peoples) join with France in the first of three wars against English colonial aggression, lasting until 1725.

- 1678: Kahnawake (formerly called Caughnawaga) is created within a Jesuit seigneury for Christian "Indians," mainly Mohawks. Many of its first inhabitants come from a nearby Indigenous Christian village under the leadership of a Wendat Christian, Tonsahoten.

- 1680: St. Kateri Tekakwitha dies at Kahnawake. People are stunned by the beauty of her face in death.

- 1681: Coureurs du bois, independent French-Canadian fur traders who evade colonial taxes and rules, and often trade alcohol for furs, are promised amnesty if they surrender. These men develop relationships (usually friendly, but not always ) with Indigenous peoples far beyond French settlement, and marry à la façon du pays ("common-law" or else in Indigenous ceremonies).

- 1683: A second Iroquois war is provoked by the governor of New France.

- 1701: The Great Peace of Montreal is signed by French and Indigenous parties.

- 1710: Port-Royal is seized by the British and renamed Annapolis Royal (after the English Queen Anne).

- 1713: By the treaty of Utrecht, France surrenders to England its colonial claims to Newfoundland and Acadia "according to its ancient boundaries." The French and English disagree where those boundaries are. The Wabanaki Confederacy resists British rule; French missionaries support them.

- 1737: Marguerite d'Youville founds the Sisters of Charity in Montreal. In later centuries this order will be conspicuous in the operation of several Roman Catholic Indian residential schools.

- 1755: The Battle of Lake George pits 1500 French, Abenaki, and Kahnawake Mohawk troops against 1500 English Americans and Haudenosaunee troops. The English win the battle after the Kahnawake Mohawks refuse to attack their kinsmen, and the Abenakis refuse to fight without the Kahanawake Mohawks.

1755: The British leaders of Nova Scotia send troops to surround Acadian churches, capture the men, and burn the settlements. So begins the forced expulsion of Acadians. Some Acadians escape deportation by taking refuge with Mi'kmaq families.

1755: The British leaders of Nova Scotia send troops to surround Acadian churches, capture the men, and burn the settlements. So begins the forced expulsion of Acadians. Some Acadians escape deportation by taking refuge with Mi'kmaq families. - 1759: In a pivotal battle of "the French and Indian War," Quebec falls to an English army.

Canada colony: sources

There are a great many sources for Indigenous and settler Christianities during the period of New France. Mostly they represent European points of view and ways of knowing.

- Jacques Cartier wrote reports and reminiscences of his voyages. Works in French are at Project Gutenberg. English translations are available in The Voyages of Jacques Cartier (University of Toronto Press, 1993). Googling the latter may bring you an on-line preview of that book.

- Samuel de Champlain's works in a century-old translation by H.P. Biggar were published in seven volumes by the Champlain Society. It has posted them online but you'll have to pay. "Internet Archive" has them for free but you need a little patience to find what you want. Project Gutenberg has these works in French.

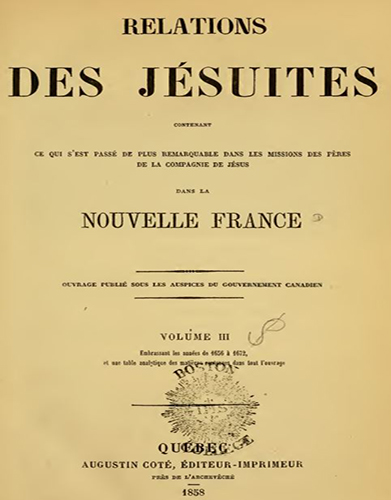

- The Jesuit Relations (Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France) are the most vital and essential source for Indigenous and settler Christianities in the period of New France. These were published as an annual periodical from 1632 to 1673. They were written by various missionaries, each of whom had his own point of view. (Resist generalizing about "the Jesuits.") The Relations report on missionary activities in various centres of New France. Many writers were interested in ethnography and minutely described the Indigenous customs that they were knew about, partly to entertain their French readers, and partly because they wanted to understand Indigenous cultures in order to make effective evangelistic appeals. The Jesuits were, of course, observing Indigenous cultures through the eyes of seventeenth-century Frenchmen; they were also writing for audiences in France whose support they wanted to curry, for financial and other reasons. So the texts need to be read "against the grain," that is, taking into account the authors' motives and premises, and looking for gaps, contradictions, defensiveness, and unintended admissions in order to get a deep se

nse of what the authors aren't saying and maybe aren't fully aware of. These works are very engagingly written and, if you can bracket their aggravating Eurocentrism, they're a pleasure to read. The originals, compiled together in 1858, filled three fat volumes, but the standard English translation with additional "allied documents" and an index makes up a 73-volume library. This was published between 1896 and 1901 under the supervision of R.G. Thwaites, a public historian in Wisconsin. It has all been scanned (but not proof-read) and made available on-line. Thwaites was, frankly, a racist, as his introductions and editorial comments show. His choice of words for translations are very often unfortunate: for instance, he equates the French "sauvage" with the English "savage," but they're different (sauvage means something like "living in the natural world"; bleuets sauvages aren't "savage blueberries"). Thwaites' editions included the original text in parallel with the translation, but the on-line version is just in English. But you can check the French versions on-line from the Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec.

nse of what the authors aren't saying and maybe aren't fully aware of. These works are very engagingly written and, if you can bracket their aggravating Eurocentrism, they're a pleasure to read. The originals, compiled together in 1858, filled three fat volumes, but the standard English translation with additional "allied documents" and an index makes up a 73-volume library. This was published between 1896 and 1901 under the supervision of R.G. Thwaites, a public historian in Wisconsin. It has all been scanned (but not proof-read) and made available on-line. Thwaites was, frankly, a racist, as his introductions and editorial comments show. His choice of words for translations are very often unfortunate: for instance, he equates the French "sauvage" with the English "savage," but they're different (sauvage means something like "living in the natural world"; bleuets sauvages aren't "savage blueberries"). Thwaites' editions included the original text in parallel with the translation, but the on-line version is just in English. But you can check the French versions on-line from the Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec. - The Champlain Society has published, and continues to publish, a real treasury of works from and about early Canada. Many of these works are digitized and are listed from this webpage, but you have to pay for them. They include writings by clergy and missionaries such as Radisson, François de Creux, and Chretien Le Clercq. Most are available from the Internet Archive (or from most Canadian academic libraries, if you have access).

- Canadiana Online includes "Early Canadiana Online," with four million pages of published works, and Héritage, which has digitized 41 million pages of archives, in both cases beginning in the 1600s. This is now free to access.

- The oral traditions of Indigenous peoples are now widely recognized by North American historians as historical evidence, though there's still some significant resistance to non-documentary sources. (Historians, after all, have been trained to analyze texts.) There's quite a literature on oral tradition as a historical source (see some suggestions in the left-hand column of this webpage), but a good straightforward introduction from the government of Alberta is here.

- Archaeology has provided considerable information about the locations of Indigenous settlements in Canada and their material culture. Archaeology in the past had a rather bad reputation among Indigenous peoples in Canada for running roughshod through sacred places, and handling sacred things profanely, but archaeological projects now are much more likely to be collaborative and respectful, with a view to serving Indigenous communities primarily, not western academic institutions.

- Pictographs can function as a form of Indigenous writing. Reference is made below to Heidi Bohaker's use of pictographs on treaties as a resource for understanding kinship structures.

- The above are mainly primary sources. Some suggestions for secondary sources are found in the left-hand column.

The settler–Indigenous context

Colonialism in New France was distinct in several ways from other North American colonialisms.

- Fur trade. The main economic basis of New France was the fur trade, which depended on alliances and cooperation between the colonizers and Indigenous

people. There was little pressure on land or need for slaves. As colonial powers go, therefore, New France wasn't particularly aggressive or coercive.

people. There was little pressure on land or need for slaves. As colonial powers go, therefore, New France wasn't particularly aggressive or coercive. - Population differences. Indigenous populations far outnumbered the colonizers. In 1630 New France had about 100 colonists, and the Wendat confederacy alone had a population of about 30,000. This proportional difference did narrow with Indigenous diseases and warfare, on the one hand, and colonial immigration, on the other. But, from an Indigenous point of view, the French colony remained a manageable factor, more useful than threatening.

- Humane ambitions. France prided itself on not being Spain. In revulsion against Spanish crimes in the new world (the "black legend"), France aimed at a more humane imperialism than its Spanish and English rivals.

- Limited emigration. France didn't encourage emigration from the old country to New France, since it believed that depopulating the mother country would be economically disadvantageous. Consequently it needed to coax Indigenous peoples into working with the colonizers. In this respect, therefore, Indigenous peoples in New France were participants in the colonial project rather than its passive victims.

- Intermarriage. Until the 1700s colonial leaders encouraged the intermarriage of French colonizers (inevitably men) with Indigenous people (inevitably women), a practice called métissage. Among Algonquian peoples, intermarriage was also often seen as advantageous. Bicultural Native wives, networked into both societies, often enjoyed a particular prestige and authority. For Iroquoian women, however, whose culture was matrilineal, marrying out into a patriarchal society had less attraction.

- Unsegregated communities. Accordingly, whereas most settler colonial regimes sought to render Indigenous peoples invisible, and to keep them beyond a frontier, the colonizers of Canada often encouraged them to move into or near the colonizers' communities along the St. Lawrence River (as long as they didn't outnumber the colonizers). In Acadia, French colonists often settled in lands inhabited by Indigenous peoples, with their permission.

No racial distinctions. Colonialism in New France wasn't racially constructed. The word "race" in the seventeenth century meant "lineage." The distinction in much modern discourse between Indigenous peoples and "whites" would have made no sense in New France. Indigenous peoples were seen as white. The first attempt at racial classification was a book by a French physician, François Bernier, in 1684. In the 1700s racialist discourse began to emerge in New France, as discussed in a recent study (by Saliha Belmessous, 2005). When Indigenous peoples didn't become like the French, the colonizers blamed their "nature," and they began discouraging intermarriage. An ideological "scientific" (i.e., pseudo-scientific) racism would blossom only in the 1800s.

French goals for Christianizing

The four main colonial interest groups were the colonial administrators, the missionaries, the trading establishment, and the habitants/habitantes who farmed.

The missionaries. The Catholic Reformation of the sixteenth century had inspired a religious revival, a zeal for missions, ministries to the poor, a focus on Christian  education, and strains of mysticism. The fruits of this movement spilled over into the seventeenth century. One result was that scores of pious French Catholics responded to a call to ordination and service in New France. Because the missionaries were thoroughly formed in a European version of Christianity, they identified Christian wisdom and discipleship with European forms of thought and cultural practice. Accordingly, they aimed not just at Christian conversion but also at the francisation ("Frenchification") of Indigenous peoples. To be precise, they wanted Indigenous peoples to be socialized into the refined and educated culture of the French bougeoisie. A recent study (by Bronwen McShea, Apostles of Empire, 2019) argues that what the colonial elite thought about Indigenous people in Canada closely paralleled what the French elite thought about the lower classes in France. If missionaries thought of Indigenous peoples as "the Other," it was an "Other" very much like the lower classes to whom the clergy were ministering in the metropolis.

education, and strains of mysticism. The fruits of this movement spilled over into the seventeenth century. One result was that scores of pious French Catholics responded to a call to ordination and service in New France. Because the missionaries were thoroughly formed in a European version of Christianity, they identified Christian wisdom and discipleship with European forms of thought and cultural practice. Accordingly, they aimed not just at Christian conversion but also at the francisation ("Frenchification") of Indigenous peoples. To be precise, they wanted Indigenous peoples to be socialized into the refined and educated culture of the French bougeoisie. A recent study (by Bronwen McShea, Apostles of Empire, 2019) argues that what the colonial elite thought about Indigenous people in Canada closely paralleled what the French elite thought about the lower classes in France. If missionaries thought of Indigenous peoples as "the Other," it was an "Other" very much like the lower classes to whom the clergy were ministering in the metropolis.

Civic leaders. French civic leaders, too, viewed their own culture and religion as superior to Indigenous peoples’, and, accordingly, they too thought that francisation and Christian conversion would be helpful to the Indigenous nations of the area. To assimilate them into French ways, they believed, was to lift them up to a better life — and, by the way, it would strengthen colonial New France. The civic leaders' strategy was gentle persuasion and voluntary intermarriage, since a tiny colonial group was in no position to force the issue on thousands upon thousands of Indigenous peoples. The first two local leaders of the colony, Champlain and his successor, the first official governor of the colony, Charles de Montmagny, were personally people of sincere piety. They trusted that God was leading history towards the conversion of the nations, and they supported missionary work to support their goal of assimilation.

A minority view has been argued by David Hackett Fischer in Champlain’s Dream (2008). He believes that Champlain was unusually tolerant for his age, and envisioned a multicultural society. However, Fischer acknowledges that Champlain identified elements in Indigenous cultures that he was unwilling to accept.

While missionaries and civic leaders thus shared the same goals, they differed in strategy. Civic leaders, especially after New France became a royal colony in 1663, wanted francisation to take priority. The Jesuit missionaries, however, learned, from some initial failures, that it was better to indulge Indigenous ways at first. Thus government officials in France wanted the Jesuits immediately to teach Indigenous peoples French and acculturate them into French manners; instead, the Jesuits insisted on communicating with Indigenous peoples in their own languages and living alongside them.

Traders. Those who depended on their adventures in New France for commercial profit, mainly in the fur trade, valued their Indigenous partners for their skills and knowledge in trapping, and for their trade networks. They were thoroughly dismayed with the prospect that the missionaries might change them, convert them, Frenchify them, and teach them to be farmers instead of hunters and trappers. In addition, for the first two decades of New France, most of the traders were Protestant, who probably thought that the missionaries’ Roman Catholicism was very little improvement over the so-called heathenism of Indigenous peoples. The missionaries were particularly nettlesome when they opposed the traders’ bartering of alcohol, their sexual licentiousness with Indigenous women, and their economic frauds and exploitations. Nevertheless, the missionaries depended financially on the economics of the fur trade, and the traders benefited from some of the social supports provided by the missionaries.

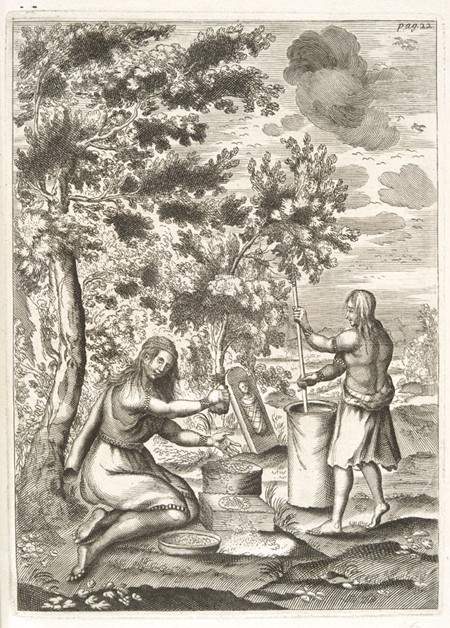

Habitants/habitantes probably had little interest in whether Indigenous peoples became Christian. They were often neighbours, and they appreciated traditoinal ecological knowledge. The colonist farmers embraced some New World foods such as beans, squash, blueberries, cranberries, butternuts, and maple syrup. They didn't catch on to corn, however; they remained committed to their wheat bread. They weren't accustomed to much meat in their diet, but they were impressed with the quantities of local fish such as eel, cod, salmon, walleye, trout, and turbot. They preferred their familiar Mediterranean olive oil over local sunflower oil.

The failure of assimilation. The colonial policy of assimilation failed since the colonial administration had no power to enforce it, and since Indigenous peoples saw little to prefer in French culture, and few worthy French models to emulate.

Mission strategies

The missionary message. Missionaries had several favourite techniques for trying to win Indigenous converts.

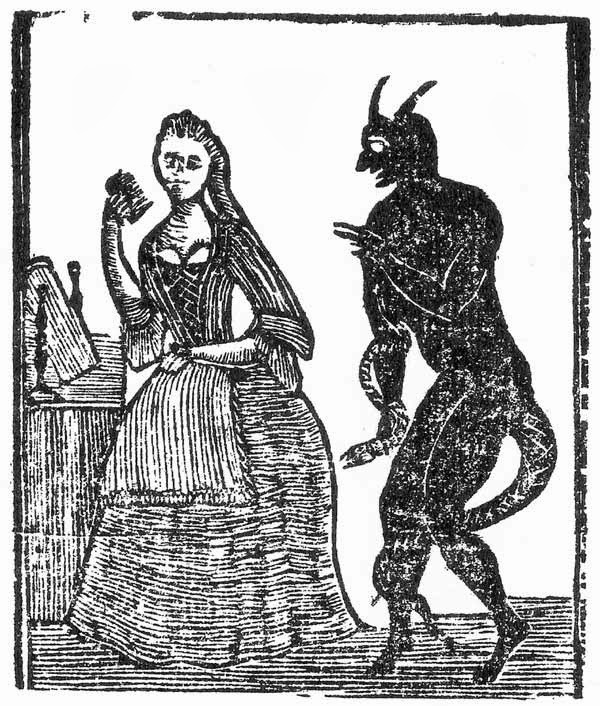

- Hell. It's remarkable how much the missionaries tried to inculcate a fear of hell in Indigenous people. Time and again, they showed them scary pictures and preached scary descriptions of hell, drawing a very dramatic binary between the agonies of hell that awaited non-Christians, and the joys of eternal life for the

baptized. This binary figured prominently in the distinctive text of Jesuit formation, the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Thus the fifth spiritual exercise of the first week was an intense meditation on the pains of hell; and a peak exercise, on the fourth day of the second week, was a meditation on "the two standards," the banner of Christ versus the banner of Satan. The message was that French Catholicism was the way of Christ, and Indigenous spiritual traditions were the work of Satan. (Modern Jesuits interpret the Exercises more subtly, for instance as an invitation to recognize that both sin and grace are always at work in us.) It doesn't appear that the missionaries succeeded in persuading many Indigenous peoples to believe in a fiery hell. In fact, the message sometimes defeated the missionaries' purpose, by indicating that, after death, Christians would be in a different place from the non-Christians that they loved. Also, many Indigenous people found the missionaries' harping on death to be puzzling and repugnant.

baptized. This binary figured prominently in the distinctive text of Jesuit formation, the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Thus the fifth spiritual exercise of the first week was an intense meditation on the pains of hell; and a peak exercise, on the fourth day of the second week, was a meditation on "the two standards," the banner of Christ versus the banner of Satan. The message was that French Catholicism was the way of Christ, and Indigenous spiritual traditions were the work of Satan. (Modern Jesuits interpret the Exercises more subtly, for instance as an invitation to recognize that both sin and grace are always at work in us.) It doesn't appear that the missionaries succeeded in persuading many Indigenous peoples to believe in a fiery hell. In fact, the message sometimes defeated the missionaries' purpose, by indicating that, after death, Christians would be in a different place from the non-Christians that they loved. Also, many Indigenous people found the missionaries' harping on death to be puzzling and repugnant. - Analogues. The missionaries frequently found in Indigenous religious culture analogues to Christian teaching and practice. As a matter of what was called natural theology, they could believe that God put into people a spiritual longing and hunger that might show itself in error but that could be used to bring them to truth. For instance, missionaries could use an Indigenous belief in a Creator as a foundation for talking about the God of Genesis 1. Thus a Jesuit reported with satisfaction in 1633, "Talking one day of God, in a cabin, they asked me what this God was. I told them that it was he who could do everything, and who had made the Sky and earth. They began to say one to the other, 'Atakocan, Atahocan, it is Atahocan.'" Similarly, a sense among Indigenous peoples of sacred places, sacred objects, and sacred rituals could serve the missionaries as a hook into Christian teaching.

- Catholic ritual interested some Indigenous people. Processions, ceremonies, statues, images, songs, and rosaries might pique curiosity. Many missionaries thought that, if Indigenous people could be induced to participate in liturgical externals, they could be nursed towards faith.

- Demonstrations of spiritual power could be evidence of the greatness of the God of Christians. Since Indigenous people already knew spiritual power, so the missionaries were often competing with shamans in prayers and rituals for healing, military defence, and good harvests. Missionaries hoped that God would perform persuasive miracles at strategic times. In the summer of 1635, when drought was threatening crops in Wendake/Huronia, Jean de Brébeuf promised the Wendat that if they resolved to serve God the Jesuits would offer nine days of masses (a "novena") to seek God's help. On the ninth day, sure enough, rain began to fall. Showers continued, and a lovely harvest resulted. In this instance, the missionaries relied on God. Sometimes they demonstrated their spiritual power in sneakier ways, such as predicting eclipses.

- Debunking Indigenous traditions. Missionaries were persuaded that Indigenous spiritual traditions were wrong — possibly works of Satan, possibly superstitions, possibly ruses by charlatan shamans, but wrong. Winning people to Christ required liberating people from error. So the missionaries opposed Indigenous tradititional spiritual practices, ridiculed and mocked them, argued against them. Their practices in this respect were profoundly divisive and destructive. Indigenous peoples had no previous experience of the idea that spiritual truths are exclusive (why couldn't new ideas be integrated into traditional teaching?). Missionaries didn't understand that Indigenous spirituality couldn't be separated

off into an autonomous sphere distinct from the rest of life, and that the message they were presenting was socially toxic.

off into an autonomous sphere distinct from the rest of life, and that the message they were presenting was socially toxic. - Superior technology. Missionaries sometimes argued that the advanced state of their technology demonstrated their great wisdom, in itself a good reason to respect their religious teaching. This reasoning was generally unconvincing, since the French were evidently inferior in their knowledge and skills in their natural surroundings.

- Winning attention. Missionaries looked for ways to gather an audience and engage them with Christian talk. They might visit Indigenous people in their homes, or invite them to their own cabin by announcements or the ringing of a bell. They might offer gifts, which in Wendake/Huronia might be tobacco. They might sing, or lead singing. If they could involve the children in a performance, the parents would be sure to pay attention, and if they then publicly rewarded the children with prizes for answering catechetical questions, the parents' hearts would be softened. In fact, hoping to help their children win prizes, they might help them learn the right answers.

- Socializing with French Christians? Some missionaries and most civic leaders thought that one of the best ways to teach Indigenous people the Christian faith was by encouraging them to socialize with French Christians. They would see Christianity in practice; Christian wisdom would come up naturally in conversation; and through their everyday relationships they would be led into church activities. Other missionaries, however, particularly the Jesuits, thought that most French Christians were very poor religious models, and that Indigenous Christians should be kept away from them.

Missionary settings. Missionaries to Indigenous peoples worked in several different settings. All of them would be repurposed later in Canadian history

- Indigenous communities. The most obvious setting for a mission was as part of a settled Indigenous community. Iroquoian-speaking peoples had such communities. In New France, the best example of such missions were those in Wendake/Huronia, first established by Récollets and later re-established by Jesuits. Sometimes they lived with the people, but more often in cabins of their own.

- Reserves. These were lands set aside for the use of Indigenous peoples, under conditions imposed by the colonizers. Often they were suitable for agriculture; in the case of so-called "nomadic" peoples, the colonizers hoped, cultivating crops might bring them into o a sedentary lifestyle. Sillery, established near Quebec in 1637 by Jesuits, is reputed to be the first reserve in Canada. The Jesuits were influenced by the example of the reducciones ("reductions") that they had established several decades earlier in Paraguay and elsewhere, as communities directed and materially supported by the Jesuits, protected from adverse European influences, nurturing Christian converts, and organizing Indigenous labour.

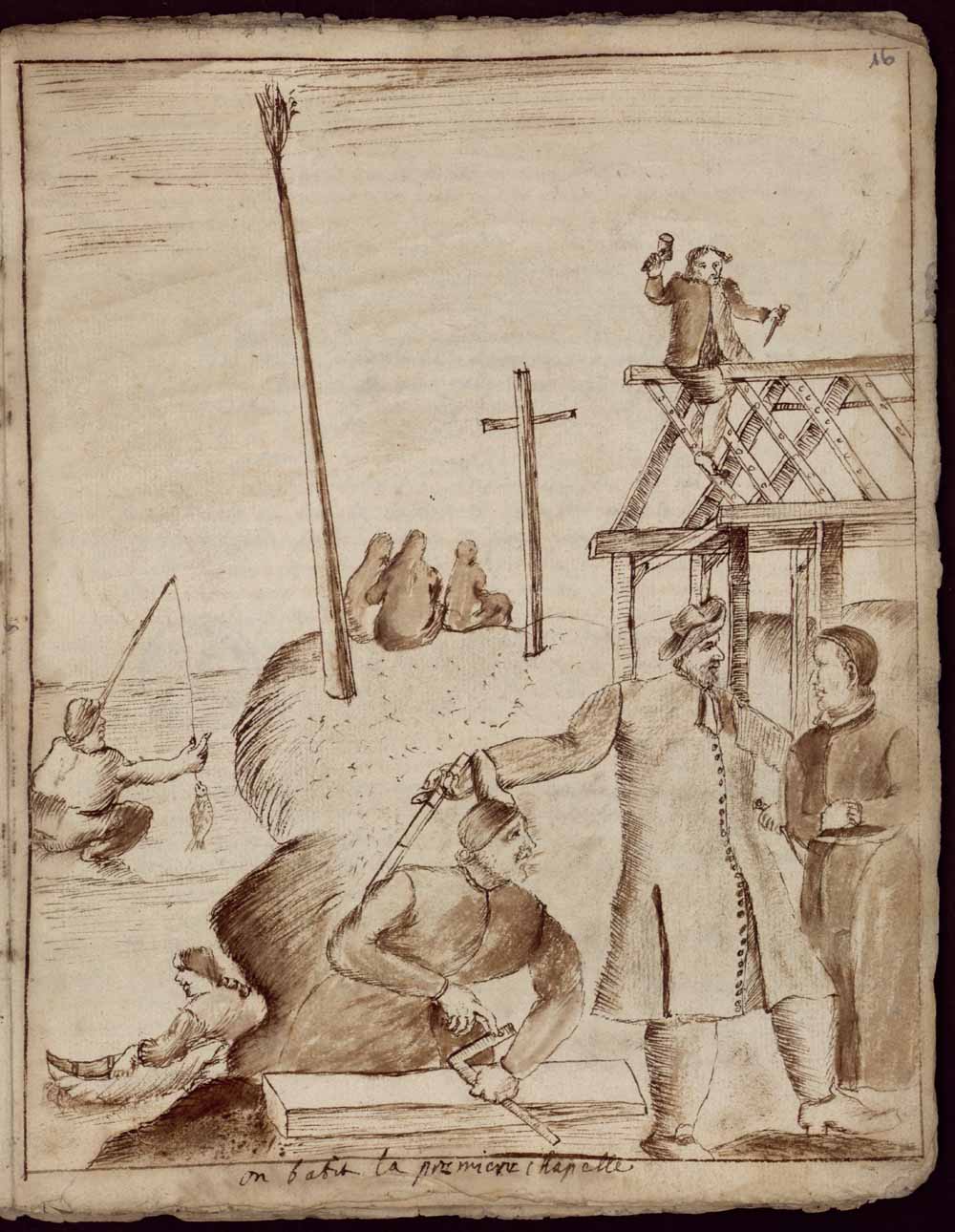

- A town. An unusual experiment was the creation of a town for Indigenous people at Ville-Marie in 1642, by a group led by a devout French Catholic, Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve, and a nurse, Jeanne Mance. They built houses, a chapel, a hospital, and outbuildings. Settlers and Indigenous peoples lived there together, and it was a meeting-place for Indigenous traders and others who were passing through. A cross was erected at the top of nearby Mount Royal. This was the beginning of the city of Montreal.

- Schools. Educating Indigenous children in a French context was considered a

charitable act, and also a strategy towards the francisation of whole Indigenous nations. In additon, educating Indigenous girls in French ways would prepare them for marriage with French men, strengthening trade and military alliances, and supporting the project of assimilation. The most noteworthy "Indian seminary" in early New France (although some French children attended as well) was the Jesuit school at Notre-Dame-des-Anges near Quebec, which opened in 1636. Of course residential schools in New France were voluntary, and the Jesuits had to convince children and parents to attend. It didn't go well. Few children attended; some got sick; some ran away; others resisted the rigid learning environment; running the school was expensive; students returning home usually left their French Christian ways behind, or, if they didn't, they were too young to bear Christian influence in their own community. As a result, the Jesuits of New France abandoned the idea of Indian residential schools. The Ursulines were a little more successful for their school for both day and boarding Indigenous girls, although Roger Magnuson, in his history of education in New France, notes the girls' chronic "cultural tug-of-war." After the 1660s, the Ursulines generally gave up their focus on First Nations girls.

charitable act, and also a strategy towards the francisation of whole Indigenous nations. In additon, educating Indigenous girls in French ways would prepare them for marriage with French men, strengthening trade and military alliances, and supporting the project of assimilation. The most noteworthy "Indian seminary" in early New France (although some French children attended as well) was the Jesuit school at Notre-Dame-des-Anges near Quebec, which opened in 1636. Of course residential schools in New France were voluntary, and the Jesuits had to convince children and parents to attend. It didn't go well. Few children attended; some got sick; some ran away; others resisted the rigid learning environment; running the school was expensive; students returning home usually left their French Christian ways behind, or, if they didn't, they were too young to bear Christian influence in their own community. As a result, the Jesuits of New France abandoned the idea of Indian residential schools. The Ursulines were a little more successful for their school for both day and boarding Indigenous girls, although Roger Magnuson, in his history of education in New France, notes the girls' chronic "cultural tug-of-war." After the 1660s, the Ursulines generally gave up their focus on First Nations girls.

Native responses to Christianity

Here are some generalizations and illustrations about the different ways that Indigenous peoples responded to Christianity. Following that, we'll focus on some specific situations.

Ignoring Christianity. During the period of New France Christianity was easy for most people to ignore. They might well hear about Christianity from friends; they might well see the missionaries in their distinctive dress; they might well hear the occasional presentation of a gospel message; but then went about their business. In August 1637, for example, we hear about an annual council of 125 Wendat people with the colonial governor at Trois-Rivières, which hopeful missionaries attended as well. The French laid out presents for the Wendat guests before the missionaries began instructing them, in order to keep them in the room. Without the presents to hold their attention, a missionary wrote, "those who have no interest in the faith rise and go away unceremoniously, as soon as one begins to speak of our belief."

Fear. Many sometimes, or always, feared the missionaries, and therefore kept the  Christian option at a distance. Reasons for fear include the following:

Christian option at a distance. Reasons for fear include the following:

- Many suspected the missionaries of sorcery or witchcraft. They saw how the missionaries administered rituals, handled sacred objects, spoke of sacred realities, made sacred signs, and seemed to exercise spiritual power. These were dangerous things to do.

- Many were afraid because the missionaries were killing people. For one thing, especially in the late 1630s, when the missionaries went out to see people, sickness and death seemed to follow. (They were spreading epidemic diseases, and they themselves had immunities.) In Wendake/Huronia in 1637, when epidemic diseases were ravaging the nation, Wendat councils considered the expulsion or death of the missionaries.

- Many were afraid because of the missionaries' administration of baptism. The missionaries were strangely focused on baptizing people. That's because the missionaries thought that unbaptized people would be eternally lost. (This belief wasn't strictly part of the Church's doctrine, since "God is not bound by God's sacraments," and Protestants found it superstitious.) The rule was that no one could be baptized without proper instruction, unless they were at the point of death. As a result, most baptisms were at the point of death. It made sense to be afraid of people whose baptismal magic led to people's death.

- Many were afraid that the missionaries, in condemning their traditional ways and sacred things, were rendering them ineffective, and leaving the people defenceless.

- Many were afraid that the missionaries might succeed in overturning their whole way of life.

- Many were afraid of the missionaries because of their secrecy and stand-offishness. The missionaries were uncomfortable with nakedness, kept away from shamanistic rituals, evidently disliked the familiarities and energies of everyday life, and weren't keen to share in a cuisine that seemed to them quite inelegant. and preferred not to live with

Seeking spiritual power. On the other hand, many Indigenous people were attracted (usually cautiously attracted) to the missionaries' apparent powers. They suffered no hurt from epidemic diseases. They could summon rain and cause eclipses. They could communicate using only paper. They had the special gifts of shamans. Especially in a time of unprecedented cultural stress, social change, and warfare, many people were keen to discover hidden knowledge, new means of control, more effective ways to protect themselves and their community, and a sense of renewal. For instance, in 1641 a young Wendat Christian was in a war canoe on a lake when a storm arose; his prayers were credited with protecting his group from shipwreck (JR 73: 173).

Seeking healing. The missionaries projected confidence in their abilities to heal,  both in medical and spiritual ways. To Iroquoian peoples, the church could seem like one of their own medicinal societies. To those who were sick, what was the down side of seeing what the missionaries could do? So many of the sick sought out the missionaries. If they were healed, however, their interest in Christianity usually subsided. In that case the Jesuits regarded them as apostates, which was even worse than being unconverted; for this reason the Jesuits were reluctant to baptize healthy adults.

both in medical and spiritual ways. To Iroquoian peoples, the church could seem like one of their own medicinal societies. To those who were sick, what was the down side of seeing what the missionaries could do? So many of the sick sought out the missionaries. If they were healed, however, their interest in Christianity usually subsided. In that case the Jesuits regarded them as apostates, which was even worse than being unconverted; for this reason the Jesuits were reluctant to baptize healthy adults.

Seeking worldly advantage. The civil authorities held out to Indigenous peoples some worldly inducements to conversion. Only Christians could obtain guns. Indigenous Christians, being French citizens, received higher prices for furs than non-Christian Indigenous traders. Christians had an inside track to trading opportunities, such as being hired to canoe. Other honours and opportunities could be heaped on Indigenous Christians, as Noêl Negabamat, an Innu convert of 1638, discovered; he often received a place of distinction at Christian and civic ceremonies. Some recognized that they the missionaries would likely give them gifts when they were baptized. A Récollet missionary in 1680 said that some "would accept baptism ten times a day for a glass of brandy or a pipe of tobacco," as Cornelius Jaenen summarizes it.

Befriending missionaries. Some Indigenous people seem to have moved into the Christian fold in order to be affirmed and appreciated by the missionaries. That's how the historian Bruce Trigger interprets some of the motivation of the Wendat Christian Chihwatenha, who begins appearing in the Jesuit Relations in 1637. He first makes a connection with the Jesuits when he's seeking healing, but, unusually, at a feast to celebrate his restored health, he publicly affirms his desire to lead a Christian life. Trigger writes that he "seems to have been attracted by the prestige, or at least the notoriety, that accrued from being the Jesuits' favoured disciple and closest Huron associate. Eventually he was to boast that in this capacity he would be remembered forever among the Huron." He's conspicuous in prayer, receiving instruction, making his confession, evangelizing other Wendat people, going through the Jesuit "Spiritual Exercises," and giving up traditional ceremonies. He was murdered in 1640, officially as a victim of the Seneca but actually, Trigger deduces, at the hands of Wendat vigilantes, who may have suspected him of being in league with the Jesuit sorcerers to harm the people.

Marrying. An important way for Indigenous women to respond to a Christian call was to marry settlers and raise Catholic families. Champlain had reportedly prophesied to a group of Wendat in 1632, "Our young men will marry your daughters, and we shall be one people." Girls might prepare for that day by being educated in the Ursuline school. Alternatively, an Indigenous Christian woman might marry an Indigenous man and convert him and then partner in the Lord's work. One example is Jeanne Assenragenhaon, a Wendat convert who married and converted a Haudenossaunee man. After he died she married a fellow Wendat, Pierre Andaiakon, and brought him into Christiantiy. They moved out of Wendake/Huronia to Quebec where they did charitable works such as taking in orphans and hosting travelers. Marriage could work both ways, however; French men were about as likely to take on Indigenous ways as Indigenous women were to take on French ways, especially in the back country of the pays d'en haut. The number of intermarriages is elusive, especially since most back-country intermarriages were celebrated à la façon du pays and not recorded.

Sending children. Indigenous Christian parents were sometimes exhorted to send their children to French schools. Children were pressed to convert to Christianity, which they may have interpreted as similar to adoption into a second Indigenous family, and they learned French ways. Seldom, however, was their transformation permanent. A recent study suggests that of all those who attended the Jesuit boys seminary at Notre-Dame-des-Anges between 1636 and 1642, only one, the Wendat boy Andehoua, remained an observant Catholic until his death. The Jesuits closed the school in 1642, as they rejected the policy of francisation as a path to conversion. The number of girls in the Ursuline school remained higher, in the hope that they would make "good" marriages with French men.

Identifying as Catholic. The record here is widely varied. By the second or third generation of New France, most Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, Innu, and Kiskakon probably readily identified as Catholic. On the othe hand, one estimate for Wendat Christians in 1649 has been one in ten of the population. The Haudenosaunee were long resistant, but, as we shall see on the next webpage, by about 1740 almost all Mohawks were Christian — Anglican in New York, Roman Catholic in Kahnawake. But in other nations, including the Ojibwe, numbers remained low.

Converting others. Although this webpage has given the impression that French missionaries were the main agents of Christianization in New France, that's likely just an effect of the limited evidence. A few dozen missionaries headquartered in a handful of locations, cultural outsiders, mistrusted by many, didn't have the reach of large Christian Indigenous populations well networked by trade, military, and kinship connections. The Jesuit Relations gives us many examples of Indigenous evangelists, and there had to be a great many more that the Jesuits knew nothing about. In 1640 Algonquins were on their way to evangelize the people of Tadoussac and beyond. In 1646 the Attikamegues, north of Trois-Rivières, receive their faith from Innu and Algonquin Christians. A little later, from a country beyond the Attikameques that the Jesuits have never heard of, come two canoes, "new faces, which appear for the first time among the French," who have heard about Christianity from some recent Indigenous converts; they are seeking instruction. About the same time, Éstiene Totiri, a Wendat, has three visions of a bloody cross in the sky; Jesus is on it, his feet in the west; and soon Totiri is taking himself westwards to evangelize the Neutral nation. The Relations are filled with many such examples.

True conversion? The missionaries hoped that Indigenous people would embrace Jesus, profess faith, repudiate Indigenous spiritual traditions, lead disciplined lives of prayer and observance, be active church members, and become acculturated as French. This seldom happened, and, in retrospect, we can be glad it didn't. For a theologian, responding to Jesus isn't necessarily performatively demonstrable, and the Jesuit themselves, in their reflective moments, acknowledged that only God can read a heart. A historian, therefore, is obliged to be agnostic about the number of true conversions, and a Christian may not even want to hold out "true conversion" as a possibility for mortal human beings. But we can believe that many formed a sense of relationship with Jesus.

The Innu

The people. The Innu were seen by the French as two distinct groups: the nearer group, with whom they had close trading connections, whom they called the Montagnais; and the farther-away group, the Naskapi. For thousands of years before European contact the Innu inhabited the territory of  Nitassinan, extending north from the north shore of the St. Lawrence River in the general area of the Saguenay River (which they called "Saki-nip," "where the water flows out"). At Kâ Mihkwâwahkâšič, near the present Quebec City, they fished for eel. At Totouskak, where Saguenay River meets the St. Lawrence, about 200 km. northeast of Kâ Mihkwâwahkâšič, they sponsored a seasonal trading station.

Nitassinan, extending north from the north shore of the St. Lawrence River in the general area of the Saguenay River (which they called "Saki-nip," "where the water flows out"). At Kâ Mihkwâwahkâšič, near the present Quebec City, they fished for eel. At Totouskak, where Saguenay River meets the St. Lawrence, about 200 km. northeast of Kâ Mihkwâwahkâšič, they sponsored a seasonal trading station.

Contact with the French. French traders developed relationships with Innu traders in the late 1500s, and in 1600 they established a permanent post at Totouskak, which they called Tadoussac. The French wanted furs; the Innu prized copper kettles, iron blades, glass, and other European products, not just for their own use but for trade with other Indigenous peoples. The Innu also valued the French as allies against their enmies the Haudenosaunee, and as friends who sometimes shared their food in a poor hunting season. Another French trading post, which the Innu permitted to be established in 1608 at what became Quebec City, also connected the French and Innu as trading partners.

Social disruption? Some historians have described the French as a disruptive influence in Indigenous social ecologies, re-ordering economies around the French fur trade, and pushing Indigenous nations towards dependence on the French. Other historians, more recently, have suggested that this picture is overdrawn. The French presence was tiny throughout the seventeenth century; and Indigenous societies, which had survived for thousands of years through a great many changes, were resilient. As for the economic impact of the fur trade, Allan Greer has pointed out that since the French wanted the beaver's soft inner fur, which was covered by coarse outer hairs, they preferred furs that the Innu had already been using for blankets and clothing long enough for the sharp hairs to fall out. In other words, the Innu simply supplied the French with their used clothing.

Pastedechouan. In 1620, when he was about twelve years old, this young Innu was taken to France. His people wanted him to go there so that he could learn French culture and language in order to train as a trade ambassador; Récollet missionaries wanted to him to go there so that they could train him to lead his people into French Christianity. In France he learned theology and the fear of hell, was baptized, and was aggressively assimilated. He returned to Canada in 1626, but by then was culturally disabled and could not regain a place in Innu society. In particular, Innu religious leaders, such as Pastedechouan's own brother Carigouan, were opposing the Eurocentrism of the Récollet missionaries. Pastedechouanh lived for a time in Tadoussac, and then relocated among the colonizers in Quebec. He had grown ambivalent about his Catholic identity and was refusing to take communion. In 1632 he connected with a newly arrived Jesuit priest named Paul Lejeune, who wanted Pastedechouan to teach him the Innu language, Lejeune worked hard to re-Catholicize Pastedechouanh. In the winter of 1633–1634, looking for an opportunity to proselytize, LeJeune joined Pastedechouan's family on an arduous hunting expedition deep in the woods to the south, using Pastedechouan as a translator. Lejeune disparaged Carigouan's religious wisdom, and demonstrated his contempt for Innu spirituality in insensitive ways. (For instance, he profaned the bones of hunted animals.) Carigouan became equally hostile toward Lejeune. Pastedechouan, ambivalent, was caught in between. After the hunt, he asked LeJeune to be reconciled to the Church: LeJeune refused, a decision which he later regretted. Pastedechouan was still residing in this ambiguity in 1636 when he died of starvation in the woods.

These relationships reflect the increasingly complex religious divisions in the Innu nation at large as Christianity gained a foothold. A religious historian at the University of Ottawa, Emma Anderson, has used Pastedechouan's story to illustrate how hard it is to understand what's going on with Indigenous Christianities. Pastedechouan was, and was not, sympathetic to his brother's traditional ceremonial practices; he was, and was not, a Christian convert; he was, and was not, an apostate. In fact, words like "traditional" and "convert" can cover many realities.

The mission at Sillery. Paul Lejeune's frustrations on the long winter hunting trip persuaded him that Indigenous peoples could best be proselytized and indoctrinated if they could be made to stay in one place mostof the time. As a result, in 1637 the Jesuits set up a mission community at Sillery, near Quebec, for Algonquin and Innu seekers, catechumens, and converts. This has been called Canada's first "Indian" reserve. The location was not chosen at random; it had long been an Innu fishing place for eel. They called it Kâ Mihkwâwahkâšič. Initially two families were invited into the community; at its peak, the reserve was home to 120 families. They received free housing, food, and clothing. They were required to farm, but they were free to leave for the hunt. They were required to learn Christianity, prepare for baptism, conform to community discipline, and obey the Jesuits.

The mission at Sillery. Paul Lejeune's frustrations on the long winter hunting trip persuaded him that Indigenous peoples could best be proselytized and indoctrinated if they could be made to stay in one place mostof the time. As a result, in 1637 the Jesuits set up a mission community at Sillery, near Quebec, for Algonquin and Innu seekers, catechumens, and converts. This has been called Canada's first "Indian" reserve. The location was not chosen at random; it had long been an Innu fishing place for eel. They called it Kâ Mihkwâwahkâšič. Initially two families were invited into the community; at its peak, the reserve was home to 120 families. They received free housing, food, and clothing. They were required to farm, but they were free to leave for the hunt. They were required to learn Christianity, prepare for baptism, conform to community discipline, and obey the Jesuits.

The good news and the bad news at Sillery.

- The good news is that the Jesuits protected the people on the reserve from European influence, just as their reducciones in Paraguay did. The brandy trade was prohibited, for example. More interestingly, the Jesuits made sure that the Innu kept their rights to fish for eel. The historian Allan Greer has described how the governor of New France tried to claim exclusive fishing rights for himself. The Jesuits protested, and they went to court, appealing to Aboriginal rights to land and resources, as well as the Christian mandate to care for the poor. When that didn't work, the Jesuits used their influence in Paris to have the governor removed. They even had seigneurial land title granted to the Christian Innu (albeit under the direction of the Jesuits!).

- The bad news is that the Jesuits practiced a coercive discipline, including whippings and public humiliations that were thoroughly inconsistent with the Innu understanding of community. Distress about the aggressive efforts at assimilation and the oppressive enforcement of rules, along with disease, Haudenosaunee raids, and fire, brought the experiment to an end in 1655.

The Algonquins

Early Algonquin Christians. The Algonquins of the Ottawa Valley became involved in the European fur trade, and by virtue of their alliance with the Innu, they could send agents to the Innu trading post at Tadoussac. Although missionary and Indigenous Christians engaged them, they were initially resistant. By the 1630s some converts were living at the Jesuit mission in Sillery. In the account of the Jesuit Relations, they asked to be admitted there when they saw that the Jesuits were inviting Innu Christians. Other Algonquin converts moved to the Jesuit mission at Trois-Rivières beginning in 1637. This settlement, founded Their departure weakened the defences of their traditional lands against the Haudenosaunee, who sought to trap there. In 1650, Haudenosaunee attacks dispersed the Algonquins from the Ottawa Valley.

Sulpician missions. With the provisional peace of 1667 and the Great Peace of 1701, Algonquins gradually returned to the Ottawa Valley; the French and Algonquins established trading posts at Abitibi and Temiscamingue in the north end of the  Ottawa Valley. Some families, however, moved to Montreal and lived there at least part-time. The Sulpicians established missions in the area in 1674, and missionaries were reportedly evangelizing about 300 Algonquins there during the summer. A major mission house began to be developed in 1676 at what is now 2065 Sherbrooke Street West in Montreal. In 1694 it was fortified to defend against Haudenosaunee attacks. (The towers are now a historic site.) In principle the Sulpicians, unlike the Jesuits, prioritized the francisation of Indigenous peoples, and the settler cultural context of Montreal seemed useful for that purpose. But proximity to the liquor trade and the generally poor example of their settler French neighbours gave them second thoughts. The Sulpicians therefore developed a mission station off Montreal island in 1703, and in 1721 they moved the Montreal mission headquarters to a much larger location at Lake of Two Mountains, just west of the island of Montreal. It was known both by its Mohawk name, Kanesatake ("sandy place"), and its Algonquin name, Oka ("pickerel"). About a hundred Algonquins joined Nipissing (who were closely related) and Mohawks there. The mission was on traditional Mohawk lands, as a two-dog wampum belt made at the time signified at the time the Sulpicians took possession. The Sulpicians, however, have denied significance of this belt.

Ottawa Valley. Some families, however, moved to Montreal and lived there at least part-time. The Sulpicians established missions in the area in 1674, and missionaries were reportedly evangelizing about 300 Algonquins there during the summer. A major mission house began to be developed in 1676 at what is now 2065 Sherbrooke Street West in Montreal. In 1694 it was fortified to defend against Haudenosaunee attacks. (The towers are now a historic site.) In principle the Sulpicians, unlike the Jesuits, prioritized the francisation of Indigenous peoples, and the settler cultural context of Montreal seemed useful for that purpose. But proximity to the liquor trade and the generally poor example of their settler French neighbours gave them second thoughts. The Sulpicians therefore developed a mission station off Montreal island in 1703, and in 1721 they moved the Montreal mission headquarters to a much larger location at Lake of Two Mountains, just west of the island of Montreal. It was known both by its Mohawk name, Kanesatake ("sandy place"), and its Algonquin name, Oka ("pickerel"). About a hundred Algonquins joined Nipissing (who were closely related) and Mohawks there. The mission was on traditional Mohawk lands, as a two-dog wampum belt made at the time signified at the time the Sulpicians took possession. The Sulpicians, however, have denied significance of this belt.

Modern disputes. After other Indigenous groupings left Oka in the 19th century, Kanesatake was left as a Mohawk community. They have provided evidence that the Sulpicians had their grant of land on behalf of Indigenous peoples, and that the Sulpicians violated the trust by using it for settler purposes. The dispute has a long history, but famously flared up in 1990 when the nearby settler town of Oka decided to take over sections of Mohawk land for a golf course. The dispute led to an armed invasion of Kanesatake by Quebec police and the Canadian military. The Oka crisis was one of the major conflicts in modern settler–Indigenous history in Canada.

The "Seven Fires" of Canada. All Algonquin converts were included in a large and influential alliance with the French called the Seven Fires or Seven Nations. The members were:

- Kahnawake

- Oka /.Kanesatake

- St-François (Sokoki, Pennacook, and New England Algonquian)

- Becancour (Eastern Abenaki)

- Oswegatchie (Onondaga and Oneida)

- Lorette (Wendat)

- St. Regis (Mohawk).

The Wendat

The people. The Wendat were a confederacy of four or more bands, with a total estmated population of 30,000. At some point before contact they had apparently had been living north of Lake Ontario, as archaeologists have uncovered palisaded Wendat sites in Pickering and Stouffville. At contact, they were in Wendake/Huronia. Like other Iroquoian speakers in the area, they cultivated farms, moving every ten years or so, as soils became exhausted. They grew the "three sisters" of corn, beans, and squash, with sunflowers and some tobacco. They lived in longhouses for a dozen or more families. Because a sedentary farming culture resembled rural France and England, the Europeans thought that the Wendat and other Iroquoian peoples were "advanced." They also hunted and fished, and participated in a considerable trading network.

Trade. In 1609, soon after the French colonists came, the Wendat initiated a trade and military alliance with them. The French responded warmly, since, with their fixed location, large population, wide trading network among both Iroquian-speaking and Algonquian-speaking peoples, and openness to partnership, the Wendat made an ideal trading partner. From then until their dispersion by the Haudenosaunee in 1649, the Wendat were New France's most important trading partners.

Trade. In 1609, soon after the French colonists came, the Wendat initiated a trade and military alliance with them. The French responded warmly, since, with their fixed location, large population, wide trading network among both Iroquian-speaking and Algonquian-speaking peoples, and openness to partnership, the Wendat made an ideal trading partner. From then until their dispersion by the Haudenosaunee in 1649, the Wendat were New France's most important trading partners.

Récollet missionaries. As a largely sedentary people and a nation friendly to the French, the Wendat were prime candidates for missionary work. Récollet missionaries made the challenging 1000-kilometre trip there in 1615, 1623, and 1626. At the Wendat settlement of Quieunonascaranas, near what's now Midland, Ontario, they met Auoindaon, chief of the Attignaouantan (Bear) nation, the largest of the Wendat confederacy. Auoindaon discerned that the missionaries were oki, influential spirits, and regarded them affectionately. He took the missionary Sagard on a month-long fishing expedition, following Wendat ways — offering tobacco, preaching to the fish, respecting the bones. In 1626 the Récollet group was joined by a Jesuit priest, Jean de Brébeuf (1593–1649). Mission work was halted while the English took control of Canada from 1629 to 1632.

Jesuit missions. In 1633, at Champlain's insistence as part of a trading agreement, the Wendat agreed to receive Jesuit missionaries in Wendake/Huronia on a permanent basis. Often Indigenous commercial arrangements involved an exchange of guests who were partly adopted relatives, partly hostages for the good treatment of Wendat traders by the French, and partly guarantors of French military assistance should Wendake/Huronia be attacked. The Wendat would become the Jesuits' single most important mission field in North America for the next fifteen years, its staff growing from three priests to nineteen, plus numerous lay workers. Until 1639 they lived in or on the outskirts of Wendat villages. Their plan was to move from village to village, turning each one Christian until the whole confederacy was Christian. The Jesuit presence divided the Wendat and generated conflict. There were many reasons to like the Jesuits personally and to be fascinated by their message, their lifestyles, and their spiritual powers. But the Jesuits brought disease in their wake, disparaged Wendat ways confrontationally, and raised suspicions.

Sainte Marie among the Hurons. In 1638 a new Jesuit superior was appointed to  head the mission, and he jettisoned the village-by-village policy. Instead he built a fortified mission settlement along the lines of a Paraguayan reducción. On the Wye River near Quieunonascaranas the Jesuits were allowed to build Sainte Marie. One area was given to Jesuit residences and an administrative headquarters for the itinerating missionaries; another area for the Wendat with traditional longhouses was divided between a Christian zone and a non-Christian zone. An advantage for the Indigenous Christians is that they could support and encourage one another; advantages for the Jesuits were that they could unify administrative arrangements and grow their own food. Today Sainte Marie is a reconstructed historical site and tourist attraction managed by an agency of the government of Ontario (pictured here).