Bahry,

Stephen. A. (forthcoming). The Potential of Bilingual Education in Educational

Development of Minority Language

Children in Mountainous Badakhshan, Tajikistan. Proceedings of the Sixth

International Conference on Language and Development, October 15-17, 2003.

Tashkent, Uzbekistan: The British Council.

The Potential of Bilingual Education in the

Educational Development

of

Minority Language Children in Mountainous Badakhshan, Tajikistan

Stephen Bahry, Ed. D. candidate, OISE/UT, University of Toronto

Comparative, International and Development Education

sbahry@oise.utoronto.ca

Abstract

The problems of

the development of the educational system of Tajikistan and Mountainous

Badakhshan Autonomous Province (MBAP) will be surveyed focusing on those that

relate to the linguistic complexity of MBAP and the language of schooling.

Evolution in language policy of Tajikistan relevant to MBAP will be outlined

followed by a review of research findings on the role of the medium of

instruction in literacy and ultimate success at school for minority language

students. There has been debate as to

whether minority language children should be introduced to literacy in the

majority language or in their first language. Further, if literacy is

introduced in the first language, how long mother tongue instruction should

continue, and when & how instruction in the majority language should be

introduced are important questions.

Language-related

problems of students in Mountainous Badakhshan province of Tajikistan, where

the majority of children do not speak Tajik, the medium of instruction in

Tajikistan, as their first language were identified in a recent study. Implications from the literature on

minority-language students’ education will be drawn for school children in

MBAP. Differences between Tajikistan’s language policy, which supports

bilingual education in MBAP and actual practice will be discussed. Questions

for further research on the relative effectiveness of various language policies

for the education of minority language children in Tajikistan will also be

proposed.

Stephen Bahry

Ed. D. Candidate, Comparative, International and Development Education

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

sbahry@oise.utoronto.ca

Education System of Tajikistan

and Mountainous Badakhshan Autonomous Province (MBAP) [1]

Tajikistan’s education system has serious problems in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union and the two-year Civil War after independence. It has insufficient infrastructure, teachers, and teaching materials, together with inadequate finances for the education system and depends on assistance from donors for its reconstruction (Niyozov, 2001; RT, 2002; UNESCO, 2000; UNICEF, 2003; WORLD BANK, 2003 a & b)

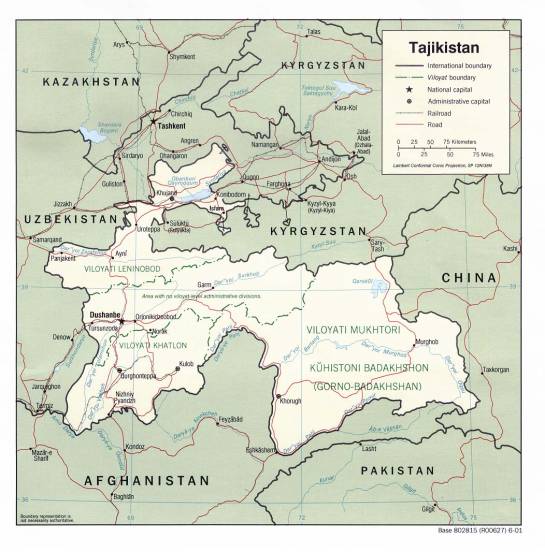

Figure 1

Political Map of Tajikistan

Source: retrieved October 13,

2003 from http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/commonwealth/tajikistan_pol01.jpg

Central government spending on education from 1992-2001 is 3 % of the total budget. Teachers’ salaries cover about 20 % of their needs, forcing them to leave teaching or supplement their incomes, sometimes with extra payments from students. Inability to afford these payments as well as clothes, shoes and textbooks causes many pupils to be absent from class (RT, 2002:22; UNICEF, 2003). MBAP is more

mountainous, and has a higher altitude than the other regions of Tajikistan, with only two roads to the outside, one to lowland Tajikistan and one over the Pamir mountains to Kyrgyzstan. After independence, there was an influx of refugees from lowland Tajikistan to MBAP, followed by a shortage of food supplies when the road from lowland Tajikistan was closed; only the provision of food aid by road from Kyrgyzstan prevented mass starvation. MBAP faces the same educational problems of Tajikistan as a whole, exacerbated by the isolation of MBAP and its extreme environment (Akbarzadeh, 1996; Niyozov, 2001; AKDN, 2002).

Mountainous Badakhshan Autonomous Province of

Tajikistan and its Linguistic Situation

MBAP is extremely

diverse linguistically, with six East Iranian languages spoken there, as well

as Tajik and Kyrgyz. East Iranian languages include Pashto of Afghanistan,

Ossetian, spoken in the Caucasus, and Yaghnobi, descended from the ancient

Soghdian language, spoken in the upper Zeravshan

valley of Tajikistan. The East Iranian languages and Tajik/Persian separated

long ago and are mutually unintelligible (Bashiri, 1997; Niyozov, 2001; Sims-Williams, n.d.).

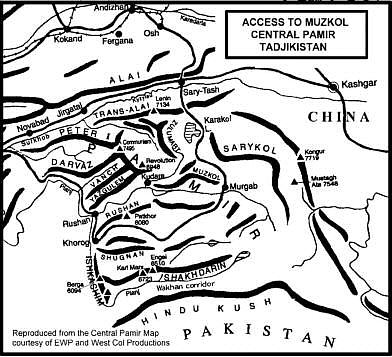

Figure 2 displays the mountain ranges of MBAP that divide the region linguistically, with most languages taking their name from the region or valley where they are found.

Figure

2

Mountainous

Badakhshan Autonomous Province

Source: retrieved October 13,

2003 from http://www.ewpnet.com/muzkol.jpg

East Iranian or Pamiri languages The right bank of the upper Panj river that separates Tajikistan from Afghanistan has a series of tributaries, whose narrow valleys are divided by high mountains. In these valleys are spoken the Pamiri

languages (Comrie, Matthews and Polinsky, 1996; Bashiri, 1997). Table 1 presents the Pamiri languages from north to south with estimated numbers of speakers of each. In Darvaz and Vanch, Pamiri languages have been completely replaced by

Tajik, and Pamiri speakers in other districts are said to have stopped using Pamiri languages in public (Bashiri, 1997; Margus et al., 2001; Dodykhudoeva, 2002b). How many speakers of these languages remain is uncertain since they have not

been counted since 1939 (Landau and Kellner-Heinkele, 2001:193). Thus, Pamiri languages are included in UNESCO’s atlas of threatened languages (Würm, 1996). Shugni, with 50,000-65,000 speakers by one setimate, is the language of the

MBAP’s

administrative centre , Khorugh, and is the Inter-Pamiri lingua franca

(Jameshedov, 2001:36; Niyozov, 2001:Ch 5).

Table 1

|

|

Language |

Estimated

Number of Speakers

1939/1940 |

Estimated Number Speakers 2001 |

|

1. |

Yazgulami |

2,000 |

3-4,000 |

|

2. |

Rushani |

5,300 |

|

|

3. |

Bartangi |

3,700 |

|

|

4. |

Shughni |

18,600 |

|

|

|

Total 2+3+4 |

27,600 |

40,000 |

|

5. |

Ishkashimi |

|

3-4,000 |

|

6. |

Wakhi |

4,500 |

20,000 |

(Margus, Tőnurist, Vaba, & Viikberg, 2001; Fillipov, 2001; Dodykhudoeva, 2002b)

West Iranian languages: Tajik/Persian Literary Tajik, based on the Tajik spoken in northern Tajikistan and in Uzbekistan, is the official language in MBAP. Used in the official institutions of the province, it is a second language everywhere in MBAP, except Darvaz and Vanch districts, where a dialect of Tajik closer to the Tajik of southern Tajikistan with elements of Pamiri language is spoken. Speakers of Pamiri languages are also said to have developed another form of Tajik, ‘Inter-Pamir Farsi’, used as a lingua franca between speakers of different Pamiri languages. Thus, at least three differing forms of Tajik are found in MBAP (Bashiri, 1997; Niyozov, 2001, Dodykhudoeva, 2002 a & b).

Turkic languages: Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz speakers form the majority in Murgab district on the Pamir

plateau. They are provided with Kyrgyz-medium schools, which use curriculum and

textbooks prepared in Kyrgyzstan. There is reportedly a high degree of

Kyrgyz/Shugni bilingualism in Murgab, with many Kyrgyz families sending their

children to Tajik-medium school (Bashiri, 1997; Niyozov, 2001).

Although speakers of Pamiri languages form a local majority in their home regions of MBAP, on a national scale they are considered speakers of minority languages. MBAP children have traditionally been educated in a second language, either Tajik or Russian.

Research on Educational Problems of Minority Language Children

Since the United Nations set as its goal the achievement of minimum standards of education, much research has been done on reducing barriers to educational achievement for all children worldwide (UNESCO, 2000b). For minority-language children, one barrier to educational achievement is the language of schooling. In industrialized countries, where educational finances are relatively strong, minority-language children still often have a higher dropout rate, lower attendance rate, poorer achievement scores, lower rates of secondary school graduation and of continuation to post-secondary study, and more frequent placement in non-academic or vocational streams compared to majority-language children.

Table 2 illustrates

national differences in high school participation and achievement in the United

States between majority language students in secondary school and minority

language students with strong and weak proficiency in the majority language.

There is a gap between enrollment of students with strong and weak skills in

the language of schooling (English), which increases as they get older.

Table 2

Percentages of

Youth Enrolled in School in USA

|

Age |

English L1 Speak

English only |

English L2 Speak English Very well |

Speak English With difficulty |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5-14 |

92.7 |

93.7 |

89.2 |

|

15-17 |

92.9 |

92.3 |

83.7 |

|

18-19 |

65.8 |

70.2 |

53.6 |

Source: US Commission on Civil Rights (1997)

Figure 3 illustrates secondary school completion rates for

minority language students in a large urban school district in Canada (Derwing,

DeCorby, Ichikawa and Jamieson; 1999). The majority of ESL students leave high

school with no diploma.

Figure 3

Figure 4 illustrates results of a longitudinal study conducted in one large Canadian urban high school on differences in completion rates between students with different English proficiency levels (Watt and Roessingh, 2001). Completion rates are quite different depending on students’ proficiency in the majority language: highest for majority language students and lowest for minority-language students with low English proficiency when beginning high school.

Figure 4

Figure 5 illustrates

results from a study of one high school in Calgary, Canada on long-term trends

in completion and drop-out rates for ESL students in secondary school (Watt

& Roessingh, 2001). Overall dropout rates are never below 60% over an

eight-year period.

Figure

5

Source: Watt & Roessingh (2001)

Figure 6 illustrates results of an analysis of differences in scores of a sample of Year 2 elementary school students in England on mathematics achievement between majority and minority language students (Hargreaves, 1997).

Figure 6

These data suggest that:

1. It is harder for minority than majority language students to complete secondary school

2. How much harder depends not only on the fact of the home – school language difference, since different types of L2 students have very different completion rates

3. Proficiency level in L2 seems to strongly affect the completion rates of minority-language students and would probably affect their transition rates to post-secondary education

These and other similar studies suggest that minority-language children’s education frequently suffers in comparison with that of other children (Skutnabb-Kangas, 1995; Baker, 1996; Cummins, 2000). A reasonable hypothesis is that minority-language children’s lesser proficiency in the language of schooling is one important factor influencing their lower participation rates, transition rates, and achievement scores in comparison to majority-language children. What theoretical explanations have been proposed for these observed differences?

Possible Theoretical Explanations of Educational Problems of Minority Language Children

Additive versus

Subtractive Bilingualism

Different types of bilingualism can be distinguished according to the relationship between L1 and L2. Additive bilingualism provides additional abilities or skills to the learner, and does not involve the new language and associated culture replacing learners’ first language and culture. Subtractive bilingualism involves the second language performing certain functions instead of the first language. Under subtractive conditions, speakers of minority languages may feel pressured to give up their language and culture to conform with the majority, or may resist learning the second language and participating in education as a means of preserving minority group language and values (Baker, 1996:66; Cummins, 2000).

Basic Interpersonal Communication Skill, Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency and the Interdependence Hypothesis

Similarly language proficiency can be divided into two types: Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills, or BICS, and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, or CALP (Cummins, 1984a, 1984b, 2000; Baker, 1996). Cummins calls proficiency in informal spoken language used for face-to-face social interaction Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills, or BICS. Typically, it involves rather simple syntax and small lexis, embedded in an interaction, with many clues to meaning in context and extralinguistic signals. BICS is relatively easily acquired by minority-language children through interaction with majority-language peers. Cummins calls proficiency in formal language used for academic purposes Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, or CALP. Typically, it involves more complex syntax, a large abstract vocabulary, with fewer redundancies, extralinguistic signals and clues to meaning lying in context and often involves higher-order abstract thought. CALP is usually acquired through exposure to written language, whether at home or school (Cummins, 2000:58-65).

Minority-language children can require several years attain grade norms in aspects of majority language CALP, 5-8 years in a typical North American English-speaking environment. Their oral proficiency in L2 social interaction does not guarantee sufficient L2 CALP for successful learning of challenging subject matter in L2. If unprepared for this difficult situation, they may be inappropriately labelled with attitude or learning problems, rather than language problems (Cummins, 1981; 2000:58-7).

Studies have found that spending time on mother tongue education in bilingual education programmes need not lead to reduced academic performance in L2 and that literacy levels in L1 and L2 may correlate significantly more strongly between L1 & L2 Reading than between L1 & L2 Oral Skills (Cummins, 2000:183). To explain such findings, Cummins (1986 cited in Baker, 1996:345), proposes the Interdependence Hypothesis: ‘To the extent that instruction through a minority language is effective in developing academic proficiency in the minority language, transfer of this proficiency to the majority language will occur given adequate exposure and motivation to learn the language’. Some aspects of CALP may be common to more than one language, permitting bilingual learners to draw on a Common Underlying Proficiency, which can be used in either language. Development of CALP in one language may facilitate further development in an additional language (Cummins, 2000:38-39).

The BICS/CALP distinction implies that minority language

children require support in learning the type of language proficiency (CALP)

that is necessary for educational success. Thus, introduction of instruction

and testing in L2 before sufficient development of L2 proficiency (both BICS

and CALP) may lead to difficulties either in learning subject matter, or in

demonstrating learning. The interdependence hypothesis may also imply that

development of L2 proficiency may be restricted if the second language is used

to replace the first language in the classroom, or if the second language is

introduced before first language proficiency is sufficiently well-developed to

permit decontextualized learning (Baker, 1996:97).

Policy Options for Education of Minority Language Children

Table 3 displays the range of policy options available to education systems to deal with minority-language children in school systems (Baker, 1996).

Table 3

Policy Options for Minority-Language Children’s

Education

|

Characteristics

of Policy

Options |

Minority Submersion Education |

Second Language

Instruction |

Transitional

Bilingual Education |

Maintenance

Bilingual Education |

|

Literacy introduced in: |

L2 |

L2 |

L1 |

L1 |

|

Medium of Instruction in Early

Primary Years: |

L2 |

L2 |

L1 & L2 |

L1 & L2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medium of Instruction throughout Compulsory Education: |

L2 |

L2 |

L1 > L2 |

L1 & L2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L2 as Second Language instruction provided? |

NO |

YES |

YES |

YES |

(Baker, 1996)

A review of 39 methodologically sound and comparable studies on effectiveness of education of language-minority students concluded students can be taught subject matter effectively in L2, as long as the teaching is done well and that progress in subject matter does not get ahead of progress in the language skills needed for study of the content, which rules out submersion as an option (Baker and de Kanter , 1983; cited in Baker, 1996: 211). A meta-analysis of 23 of these studies concluded that bilingual education that supports the minority language consistently produces superior outcomes with advantages in achievement in reading, math, language skill, and overall achievement compared to students in second language or submersion environments (Willig, 1985; cited in Baker, 1996: 213).

These studies conclude bilingual and/or second language instruction support minority-language students’ education. Tables 4 and 5 display conditions identified by other researchers as facilitating achievement among minority language children, who conclude bilingual education is more supportive of minority language students’ needs than second language instruction or submersion.

Table

4

|

|

Conditions Facilitating

Minority-Language Children’s Success

|

|

1. |

School leaders clearly committed to educational success of minority-language students |

|

2. |

L2 is

important but L1 is promoted throughout curriculum and labeled as advantage

not liability |

|

3. |

Teachers know current effective approaches

for teaching minority-language children |

|

4. |

Teachers committed to empowerment of students and participate in activities developing that commitment |

|

5. |

Students provided with variety of courses in both languages with small class sizes |

|

6. |

Students provided with career and study counselling and have achievement monitored |

|

7. |

Parents encouraged to contact teachers and

counselors and participate in meetings |

|

8. |

Students provided with high expectations

for success and strong support |

Lucas, Henze and Donato (1990), cited in (Baker, 1996: 220)

Table

5

|

|

Conditions Facilitating

Minority-Language Children’s Success

|

|

1 |

Mother tongue main medium of education, especially during

first 8 years |

|

2 |

All children know OR alternate equally between knowing and

not knowing language of instruction |

|

3 |

All teachers are bilingual |

|

4 |

Foreign languages should be taught through children’s

mother tongue and/or by teachers who know it |

|

5 |

All children study both L1 and L2 as compulsory subjects

through grades 1-12 |

Skutnabb-Kangas (1995:12-14)

Cummins (1986; cited

in Baker, 1996:394-396) suggests that minority language students are

“empowered” by incorporating the home language and culture into the school

curriculum, involving parents in their children’s education, and regarding the

learning process as not mere transmission of knowledge with the learners as

passive recipients. Table 6 provides a selection from a curriculum attempting

to provide many of the above facilitating or empowering conditions.

Table 6

Multilingual Curriculum of the European Schools[2]

|

|

SUBJECT |

Grades 1 & 2 |

Grades 3, 4 & 5 |

Grades 6 & 7 |

Grade 8 |

Grades 9 & 10 |

Grades 11 & 12 |

|

Languages |

L1 as a Subject |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 (advanced) |

|

|

L2 as a Subject |

L2

|

L2

|

L2

|

L2

|

L2 |

L2

(advanced)

|

|

|

L3 as a Subject |

|

|

L3

|

L3

|

L3

|

L3 (opt) |

|

|

Classical Languages (opt) |

|

|

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

|

|

L4 as a Subject (opt) |

|

|

|

|

L4 |

L4 |

|

Math/Science |

Mathematics |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 (advanced) |

|

|

Integrated Science |

|

|

L1 |

L1 |

|

|

|

|

Biology |

|

|

|

|

L1 |

L1 |

|

|

Chemistry |

|

|

|

|

L1 |

L1 (advanced) |

|

|

Physics |

|

|

|

|

L1 |

L1 (advanced) |

|

Social Science |

Environmental Studies |

L1 |

L1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human Sciences |

|

|

L1 |

L2

|

|

|

|

|

Geography |

|

|

|

|

L2 |

L2 (advanced) |

|

|

History |

|

|

|

|

L2 |

L2 (advanced) |

|

|

Economics & Social Science (opt) |

|

|

|

|

L2 (opt) |

L2 (opt) |

|

Other |

Music |

L1 |

L1 |

L2 |

L2 |

L2 (opt) |

|

|

|

Art |

L1 |

L1 |

L2 |

L2 |

L2 (opt) |

|

|

|

Physical education |

L1 |

L2 |

L2 |

L2 |

L2 |

L2 |

|

|

Religion OR Ethics |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L1 |

L2 |

|

|

Philosophy |

|

|

|

|

|

L1 |

Source:

Baetens Beardsmore (1995) in Skutnabb-Kangas (1995)

Language

Policy in Tajikistan

During perestroika, Tajikistan and the other republics of

Central Asia declared the “titular” language of their respective republics to

be the official language. After independence, the titular languages of the each

country may have been seen as necessary unifying symbols for the state

(Schlyter, 2001). Nevertheless, the Language

Law of 1989 guaranteed free use of minority languages everywhere, including the

languages of MBAP (Landau and Kellner-Heinkele, 2001:114 & 122; Professor

D. Karamshoev, personal communication October, 6, 2003).

In 1993, the Law on Education was decreed, Articles 5 and 6

of which made Tajik the language of instruction, while permitting instruction

to be given in other languages in ‘compact settlements of minority groups’ (Landau and Kellner-Heinkele, 2001:122). In

1994, Article 2 of the revised Constitution allowed every national group to use

its own native language freely (RT, 1994), but did not specifically include

speakers of Pamiri languages, who are not considered to be ‘national groups’

(Landau and Kellner-Heinkele, 2001:193).

In 1997, the Dodkhudoeva Commission’s report on Implementation

of the 1989 Language Law was adopted recommending that Tajik be taught in all

schools, no matter what the main medium of instruction and that Kyrgyz, Uzbek

and East Iranian languages should receive special consideration in areas where

there are concentrations of speakers of these languages. Instruction in their

own language together with Tajik was guaranteed at the elementary school level

for children whose mother tongue was one of the East Iranian languages (Landau

and Kellner-Heinkele, 2001:105-6, 195).

Thus, the interrelated language policies have a common

theme of encouraging wider use of Tajik and permitting greater use of minority

languages than in the Soviet period. However, the policies regarding the use of

minority languages are not completely consistent with each other. Speakers of

East Iranian languages are considered linguistic minorities but not national or

ethnic minorities, while speakers of Turkic languages are considered members of

ethnic, national and linguistic minorities. This means that the policies

referring to languages of national or ethnic minorities do not include speakers

of the East Iranian languages of Tajikistan.

Thus the constitutional guarantee of free use of minority

languages of national groups excludes East Iranian languages. At the same time,

in areas of compact settlement of speakers of East Iranian languages, the 1993

Law on Education permits but does not guarantee the use of East Iranian

languages as medium of instruction, while the Dodkhudoeva Commission recommendations

on implementation of the Language Law of 1989 guarantees the use of East

Iranian languages as media of instruction.

While post-independence language policy seems to allow the

use of Pamiri languages in MBAP in the school system, and to guarantee their

use in elementary school, implementation of policy may be delayed for various

reasons, such as continued use of Soviet models for curricula lack of finances

for development and printing of new curricula (UNDP, 1996).

Linguistic Situation in MBAP Schools

Despite recent policy, Niyozov claims that teachers of

Pamiri-speaking children do not allow free use of Pamiri languages in the

school system, partly to avoid clashes with school inspectors yet they have few

Tajik language materials to implement Tajik language instruction (2001:243,

270, 338, 343).

Dodykhudoeva (2002a, 2002b) states that all instruction in

MBAP is conducted in Tajik with no provision of classes in Tajik as a Second

Language (TSL), while Niyozov (2001:361) states that to ease transition to

all-Tajik instruction, TSL instruction is provided to Pamiri-speaking children

for one year of preschool, although attendance is low: 30 % of boys, 20 % of

girls (RT, 2002). Teachers mention teaching Tajik Language and Literature, but

no systematic teaching of Tajik as a Second Language (Niyozov, 2001), although

TSL materials development and teacher development courses are now being

undertaken at the Institute of Professional Development in Khorugh, the capital

of MBAP (AKDN, 2002).

Treatment of Pamiri-speaking minority language children as described by Dodykhudoeva (2002 b) and observed by Niyozov (2001: 149-277) can be classified as “Submersion”, since literacy is introduced and formal teaching is done in a second language, Tajik or Russian. Although teachers in schools with Pamiri-speaking students observed by Niyozov frequently resort to Pamiri language in the classroom, the situation is still “Submersion” since there is only incidental support from individual teachers with no systematic official support for language learning problems of minority-language children, whether through some form of Bilingual Education as provided for by the language policy of Tajikistan, or TSL instruction.

Evidence for Educational Problems with the Language of Instruction of MBAP Children

Niyozov (2001) conducted a comparative case study of two teachers in two different Tajik-medium schools in MBAP. The methodology of the study involved in-depth interviews and discussions with teachers about their teaching rationale and observing, taping and transcribing lessons and interactions between teachers and students, noting languages used. Both teachers studied claim students’ learning is exacerbated by receptive and productive language problems with their second language, Tajik or third language, Russian.

Some students’ Tajik proficiency is insufficient to comprehend lessons adequately (2001: 251), especially since the curricula and texts are too abstract for comprehension in their second language (2001: 299). Weak expressive ability in Tajik makes some unable to express their understanding clearly (2001:251, 257) causing them to receive lower marks (2001:259) and to feel reluctant to speak in class due to anxiety about being ridicule as well as lower marks.

A survey of observations recorded by Niyozov (2001:119-278) was made to identify the presence or absence of recommended preconditions for successful education of minority language students in the education of Pamiri-language children in the MBAP classes observed (see Tables 7 & 8) [3].

Table 7

Presence of Skutnabb-Kangas’

Preconditions

|

|

Presence

|

|

Conditions Facilitating Minority-Language Children’s Success

|

|

|

NO |

1 |

Mother

tongue main medium of education, especially during first 8 years |

|

|

NO |

2 |

All

children know OR alternate equally between knowing & not knowing language

of instruction |

|

|

YES |

3 |

All

teachers are bilingual |

|

|

YES |

4 |

Foreign

languages should be taught through children’s L1 and/or by teachers who know

it |

|

|

NO |

5 |

All

children study both L1 and L2 as compulsory subjects through grades 1-12 |

Based on: Skutnabb-Kangas (1995) and Niyozov (2001)

Table 8

Presence of Facilitating Conditions Lucas et al.

Presence

|

|

Conditions Facilitating

Minority-Language Children’s Success

|

|

NO/YES |

1. |

School leaders clearly committed to educational success of minority-language students |

|

NO |

2. |

L2 is

important but L1 is promoted throughout curriculum and labeled as advantage |

|

NO/YES |

3. |

Teachers know current effective approaches

for teaching minority-language children |

|

YES |

4. |

Teachers committed to empowerment of students & develop that commitment through activities |

|

NO |

5. |

Students provided with variety of courses in both languages with small class sizes |

|

NO/YES |

6. |

Students provided with career and study counselling and have achievement monitored |

|

YES |

7. |

Parents encouraged to contact teachers and

counselors and participate in meetings |

|

YES/NO |

8. |

Students provided with high expectations

for success and strong support |

Based on: Lucas et

al. (1990) and Niyozov (2001)

Minority language students may be empowered

by incorporating the home language and culture into the school curriculum,

involving parents in their children’s education, and regarding the learning

process as not mere transmission of knowledge with the learners as passive

recipients (Cummins, 1986). Niyozov (2001) shows that teachers observed respond

to students’ language-related difficulties by adapting their teaching

informally to include local language, culture and community in the learning

process to “empower” their students.

One teacher simplifies the Tajik of the

curriculum to make it more comprehensible (2001:251), and provides

supplementary explanation in Shugni, integrating local experience and

environment into lessons through extra-curricular activities where the teacher

feels freer to use Pamiri language for instruction and discussion than in

school, despite recent official policy (Niyozov, 2001: 207-278). Both report a

greater need to use Shugni than before, and a greater willingness to “adapt”

the medium of instruction. Yet in class, teachers’ merely supplement lessons

with Shugni to motivate students and resolve communication failures, for fear

of being criticized by authorities or parents (Niyozov, 2001: 138, 236, 249,

362).

Questions for Further Research:

Niyozov (2001:438-439) proposed several areas for research focusing on language-related issues (see Table 9).

Table 9

|

Language-related Topics for further research in MBAP schools |

|

A Language of instruction and interaction in education inside and outside classroom |

|

B Attitudes of stakeholders about the languages of MBAP and the language of instruction: Students’, parents’, teachers’ and administrators’ |

|

C How students can learn other languages, such as Tajik, Russian and English without this process leading to the marginalization of local languages and cultures |

Niyozov

(2001:438-439)

Topics A & B

In fact, data for research on Topic A & B already exist. Niyozov (2001) provides several transcripts of student-teacher interactions where shifts in language are identified, and comments on the language issue and attitudes of teachers, administrators and parents.

Niyozov’s raw notes and transcripts of all lessons and interviews with teachers and administrators would provide a wealth of data for further research. A detailed reanalysis of this material by a researcher familiar with Pamiri languages, Tajik and Russian would be an invaluable preliminary study in the design of further research in these areas.

Topic C

The research cited above suggests that far from marginalizing local language and culture, bilingual education can support the maintenance of local language and culture, while simultaneously facilitating acquisition of second, third, fourth and even fifth languages. Conditions of additive bilingualism are needed to replace conditions of subtractive bilingualism. Here are some possible questions for further research in addition to those proposed by Niyozov (2001):

1. Are there significant differences in participation, transition, completion and achievement between schools or districts in MBAP where students are educated in their first language (Tajik-medium schools in Darvaz and Vanch) (Kyrgyz-medium schools in Murgab) and schools in MBAP where students are educated in their second language (Tajik-medium schools in Pamiri-speaking districts)

2. Under what conditions are higher levels of participation, transition, completion, and achievement

of minority-language and other students found?

3. What are the comparative effects on minority-language student participation, transition, completion, and achievement of different types of language support for minority-language students in MBAP:

A Submersion – minimal support for minority language students

B Tajik as a Second Language instruction

C Transitional Bilingual Programme

D Maintenance Bilingual Programme

Preliminary research on Question #1 can be done with existing school data using individual schools or districts as the basis for comparison. Significant differences between schools or districts using L1 and L2 as medium of instruction would be suggestive that language might significantly affect dependent educational variables.

Question #2 could be carried out under present circumstances on a school-by-school or district-by-district basis. To do so, information about student characteristics, teacher characteristics, school characteristics can be gathered allowing comparison with levels of student participation, transition, completion, and achievement. Teacher characteristics should include information about teaching practices, especially relating to language of instruction. Student and teacher characteristics should include languages spoken at home and educational background of family.

Research on Question # 3 can only partially be carried out at present, since only Options A and B exist in the public school system, and provision of TSL Instruction is uneven throughout the province. With the detailed information outlined in question #2, careful comparison of Options A and B can be made and establishing a baseline for later comparison of Options C and D.

This research will have to wait until completion of work on curriculum, materials and teacher preparation for the delivery of bilingual education in East Iranian languages and Tajik begins to be implemented. In the interim, preliminary research is needed in these areas. Such work has already begun for TSL instruction. The Institute of Professional Development in Khorugh, MBAP has begun work on new TSL materials and is providing TSL teacher training (AKDN, 2002).

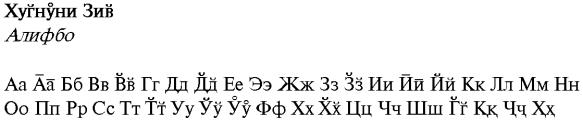

A basis for this work on Pamiri curriculum and materials already exists. Although Pamiri languages are traditionally unwritten, a Latin script was developed for Shugni in the 1920s and more recently a Cyrillic Alphabet for Shugni has been developed (see Figure 7), which is increasingly used since for books, children’s primers, and in the press, mainly for poetry and short stories (Wennberg, n.d.; Niyozov, 2001:361).

Figure 7

Professor Karamshoev’s new Shugni alphabet

Source: Wennberg (n.d.)

Tajikistan’s language policy concurs with research on the education of minority language children on the need for mother tongue education in MBAP. However, there has been a lag between formation of policy and development of a capacity for instruction in the Pamiri languages, presumably due to financial and logistical restrictions. Professor D. Karamshoev, a leading expert on Pamiri languages, and a member of the Dodkhudoeva commission, believes that to implement the Tajikistan’s language policy regarding local languages in MBAP, increased support, material and non-material, for development of curriculum and preparation of teachers of minority languages is required from the Ministries of Education of Tajikistan and MBAP, national and international language and curriculum experts, and international educational development organizations (personal communication, October 6, 2003).

Research on the experience of the Russian Federation on implementation of mother tongue education in “smaller” languages may prove fruitful. Leontiev (1995) reports 22 minority languages being used as media of instruction at various levels, including Ossetian, the only East Iranian language to be used as a medium of instruction in the former U.S.S.R. (see Table 10). This suggests that mother tongue education in smaller languages in post-Soviet conditions is financially feasible.

Table 10

Languages used as

Media of Instruction in Russian Federation

|

Years Used as Medium of Instruction |

Number of Languages |

|

1-Higher

Education[4] |

1 |

|

1-11 |

3 |

|

1-9 |

1 |

|

1-7 |

3 |

|

1-4 |

15 |

Source: Leontiev (1995)

Development of curriculum and teachers for Pamiri-language instruction in MBAP provides an opportunity to make the content of the MBAP curriculum more relevant to children, while making the language of the curriculum more accessible, not only to Pamiri-speaking children, but also to their parents, whose support of and understanding of their children’s curriculum is an essential part of their children’s educational success.

Effective mother tongue and TSL instruction ensures that the use of Tajik as a medium of instruction for key subject matter does not precede students’ development of Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency in Tajik. By creating conditions of Additive Bilingualism, there should be a positive effect on students’ comprehension of subject matter, their ability to express their understanding, and proficiency in Tajik as a Second Language, all of which can have a positive effect on attitudes of students towards schooling and ultimately their scholastic achievement.

References

Akbarzadeh, Shakhram (1996). Why did Nationalism fail in Tajikistan? Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 48, No. 7 1105-1129

AKDN (2002). AKF Activities in Tajikistan. Report of Aga Khan Foundation retrieved Sept 29, 2003 from http://www.akdn.org/akf/tajikrep_02.pdf

Baetens Beardsmore, H. (1995). The European School Experience in Multilingual Education. Ch 1 in Skutnabb-Kangas (ed.) (1995).

Baker, Colin. (1996). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters

Baker, K.A. and de Kanter, A.A. (1983). Bilingual Education. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books

Bashiri, Iraj (1997). The

Languages of Tajikistan in Perspective. Retrieved from

http://www.iles.umn.edu/faculty/bashiri/Tajling%20folder/Tajling.html

July 30, 2003

Comrie, B. Matthews, S. and M. Polinsky (eds.) (1996). The atlas of languages: the origin and development of languages throughout the world. New York: Facts on File

Cummins, James (1981). Age on Arrival and Immigrant Second Language Learning in Canada: A Reassessment. Applied Linguistics, Vol. 2, No. 2

Cummins (1986). Empowering minority students: A framework for intervention. Harvard Educational Review 56 (1), 18-36175

Cummins, Jim (2000). Language,

Power and Pedagogy: bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon, UK:

Multilingual Matters

Cummins, Jim and Swain, Merrill (1986). Bilingualism in Education: Aspects of theory, research and practice. New York: Longman

Derwing, T., DeCorby E. Ichikawa, I. and K. Jamieson. (1999). Some Factors That Affect the Success of ESL High School Students.

The Canadian Modern Language Review, 55, 4 (June)

Dodykhudoeva, Leila (2002a). ‘The sociolinguistic situation and language policy of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan: The Case of the Tajik Language’

paper presented at World Congress on Language Policies, Barcelona. Retrieved Aug 8, 2003 from http://www.linguapax.org/congres/taller/taller2/Dodykhudoeva.html

Dodykhudoeva, Leila (2002b). ‘The sociolinguistic situation and language policy of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan: The Case of the North Pamir Languages’

paper presented at CELEUROPA conference on Sociolinguistics & Language Planning in St. Ulrich, Switzerland Retrieved Aug 8, 2003 from http://www.geocities.com/celeuropa/AlpesEuropa/Urtijei2002/Dodykhudoeva.html

Fillipov, Vassily (2001). Case Study No. 227. Local

self-government of Pamir people in Badakhshan Mountains, Republic of

Tadjikistan, 1996-2001 and beyond. Centre for Civilization

and Regional Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved Sept 29, 2003 from http://lgi.osi.hu/ethnic/csdb/index.html

Hargreaves, Eleanore (1997). Mathematics Assessment for Children with English as an Additional Language. Assessment in Education, Vol. 4, No. 3

Jamshedov, P. (2001). The Roof of the World. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: Shugnanica

Landau, Jacob M. and Kellner-Heinkele, Barbara (2001). Politics of Language in the Ex-Soviet Muslim States. London: Hurst and Co.

Leontiev, Alexei A. (1995).

Multilingualism for all – Russians? Ch.

8 in Skutnabb-Kangas (ed.) (1995).

Lucas, T., Henze, R. and Donato, R. (1990). Promoting the Success of Latino language-minority students: An exploratory study of six High Schools.

Harvard Educational Review 60 (3), 315-340

Margus K., I. Tönurist, L. Vaba, and J. Viikberg. (2001). The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Tallin, Estonia: NGO Red Book. also available online at

http://www.eki.ee/books/redbook/pamir_peoples.shtml

Niyozov, Sarfaroz (2001). Understanding Teaching in

Post-Soviet, Rural Mountainous Tajikistan: Case Studies of Teachers Life and

Work.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Nunan, D. (1988). The Learner-centred Curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Republic of Tajikistan (RT) (1994). Constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan: excerpts. retrieved fromhttp://www.law.tojikiston.com/english/index.html retrieved September 19, 2003

Republic of Tajikistan (RT) (2002). Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. retrieved July 30, 2003 from http://www.reliefweb.int/library/documents/2002/imf-tjk-09oct.pdf

Schlyter, Birgit N. (2001). Language Policies in Central Asia. MOST Journal on Multicultural Societies, vol. 3, no. 2 Retrieved July 30, 2003 from

http://www.unesco.org/most/vl3n2edi.htm

Simms-Williams, Nicholas (n.d.) Eastern Iranian Languages. Retrieved October 6, 2003 from http://www.iranica.com/articles/v7/v7f6/v7f659.html

Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove. (ed.) (1995). Multilingualism for All. Swets

and Zeitlinger: Lisse, Netherlands

UNDP (1996). United

Nations Development Programme Tajikistan Human Development Report 1996. Retrieved

from http://www.undp.org/rbec/nhdr/1996/tajikistan/chapter11.htm

UNESCO (2000a). The EFA 2000 Assessment: Country Reports

Tajikistan. Retrieved from

http://www2.unesco.org/wef/countryreports/tajikistan/rapport_1.html July 30,

2003

UNESCO(2000b)

Thematic Studies: Textbooks and Learning Materials 1990-1999. World Education Forum, Dakar, Senegal April

2000 Education for All 2000 Assessment

Retrieved from

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001234/123487e.pdf August 8, 2003

UNICEF (2003) Tajikistan at a glance. retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/Tajikistan_14039.html Sep 29, 2003

US Commission on

Civil Rights (1997). Equal Educational

Opportunity and Nondiscrimination for Students with Limited English

Proficiency: Federal Enforcement of Title VI and "Lau v.

Nichols." Equal Educational

Opportunity Project Series, Vol. III. Washington, D.C. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED415600)

Watt, D. and Roessingh, H. (1994). ESL Dropout: The myth of educational equity. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 3, 283-296

Watt, D. and Roessingh, H. (2001). The Dynamics of ESL Dropout: Plus Ça Change… . The Canadian Modern Language Review, 58, 2 (December) 203-222

Wennberg, Franz

(n.d.) Shugnani. Retrieved July 30, 2003 from

http://www.afro.uu.se/forskning/iranforsk/Franzbilder/shughnani.htm

Willig, A.C. (1985). “A meta-analysis of selected studies on

the effectiveness of bilingual

education”. Review of Educational

Research, 55 (3), 269-317

World Bank

(2003)a. Tajikistan Country Brief. retrieved from

http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/ECA/eca.nsf/ExtECADocbyUnid/936613239604B1685256D800057B35E?Opendocument World Bank (2003)b. Tajikistan Country Assistance Strategy. Retrieved Sept 29, 2003 from http://wwwwds.worldbank.org/

Würm, Stephen A.

(1996). Atlas des langues en peril

dans le monde. Paris: UNESCO