Bahry, Stephen A. (2005, forthcoming). Language, Literacy and Education in Tajikistan.

In The Domestic Environment of

Central and Inner Asia. Toronto

Studies in Central and Inner Asia No.7, Asian Institute, University of Toronto,

2005.

Stephen A. Bahry, doctoral

candidate,

Comparative, International and

Development Education Centre,

Ontario Institute for Studies in

Education /University of Toronto

252 Bloor St. West, Toronto,

Ontario CANADA M5S 1V6

sbahry@oise.utoronto.ca

LANGUAGE, LITERACY AND EDUCATION IN TAJIKISTAN

Stephen A. Bahry

EDUCATION IN SOVIET TAJIKISTAN

Education in the Tadzhik Soviet

Socialist Republic was relatively strong. The USSR had achieved basic and lower

secondary education for all citizens, near-universal adult literacy, relatively

high levels of achievement and relatively low disparities in access to

education.[1]

At the beginning of the Soviet era, literacy levels in Tajikistan were

estimated as quite low, approximately 2.3% of adults,[2]

yet in 1955 there were 45 secondary or higher education students per 1,000

population in Central Asia, compared to 23 per 1,000 for India and 5 per 1,000

for Iran at the same time, an indication of the relatively high level of

educational development in Central Asia in the Soviet period.[3]

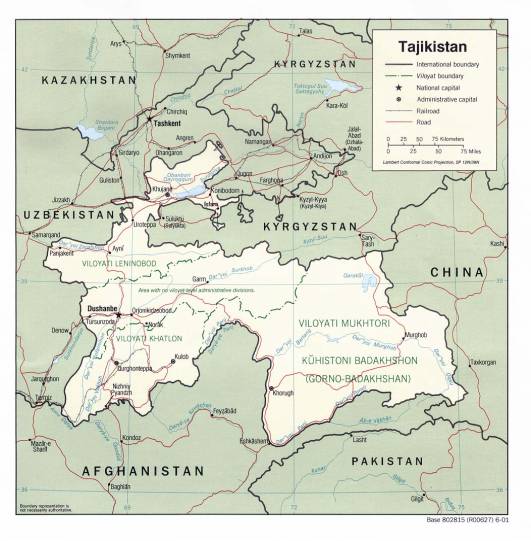

Figure 1

Source:

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/commonwealth/tajikistan_pol01.jpg

Despite these accomplishments, accumulating economic and political

problems had a negative effect on children’s learning and the provision of

education, particularly in Central Asia. In the last decade of the USSR, the

period of Perestroika, or Reconstruction, an estimated 60% in the Tadzhik

S.S.R. lived below the poverty line, with 60% of children in Central Asia

estimated as suffering from malnutrition and diseases related to poverty.

Reports of reduced provision of education typical of less developed countries

began to appear more frequently in Soviet press and journals during the period

of Perestroika, including shortages of teachers, and of textbooks.[4]

EDUCATION IN THE INDEPENDENT REPUBLIC OF

TAJIKISTAN

PROBLEMS OF THE SYSTEM

Curriculum

The Republic of Tajikistan gained its independence in 1991 on the collapse of the Soviet Union. On independence, textbooks, especially in humanities subjects, became obsolete: new curricula and textbooks were required and old textbooks were in some cases withdrawn before new ones were in place.[5]

Curriculum, materials and teachers for schools where the medium of instruction was not Tajik were also formerly provided by the sister republics of Central Asia. For example, the Kyrgyz S.S.R. provided for the Kyrgyz-medium schools in the Tadzhik S.S.R. and the Tadzhik S.S.R. for the Tajik -medium schools in the Kyrgyz S.S.R. But now these are all to be provided by the Republic of Tajikistan. New curricula must be developed in several languages, textbooks prepared and published, and many teachers trained,[6] all of which involve increases in the financial demands of education in Tajikistan.

Impact on Learning

Inability to afford ‘informal’ payments to teachers

and schools, as well as the cost of clothes, shoes and textbooks causes many

pupils to be absent from class.[7]

Many classrooms have only one copy of the textbook for each subject, which

leaves teachers and students with no choice but to waste much time copying

textbook summaries on to and from the board.[8] Thus,

the lack of textbooks and other teaching materials and experienced,

well-trained teachers means that the potential for learning of those children

who regularly attend school is less than before independence. This, combined

with large-scale absenteeism of children whose families cannot afford the costs

of schooling threatens Tajikistan with a major regression in basic literacy and

numeracy skills of the coming generation.[9]

Dependence on External Support

Tajikistan’s education system depends on assistance from donors for its reconstruction; for example, the World Bank’s donations alone amount to 10% of Tajikistan’s total education budget.[10] Consequently, the attitude of this and other external educational development agencies is likely to have a profound effect on changes in education in Tajikistan.

The World Bank is critical of the curriculum and pedagogy inherited from the Soviet era and focuses much of its recommendations for change in Tajikistan, for example, on increasing emphasis on skills development and problem-solving over the retention of masses of factual material, because it is ‘essential’ to develop necessary skills for the ‘new’ economy.[11] Some of this critique of the tradition of Soviet-style education was raised by Soviet educators during Perestroika;[12] however, Tajikistan is unique in having the civil war to blame for problems in education, and may attribute problems in education to causes external to the education system and less to weaknesses in the system itself. Thus, Tajikistan is relatively tolerant of continued use of Soviet-style curriculum, either as reprints or adaptations of Soviet-era textbooks,[13] while the World Bank’s vision involves a greater restructuring of education.[14] A comparative study of the priorities for textbook development in Tajikistan of the government and the World Bank found interesting differences, which are displayed in the table below.[15]

Table 1

Priorities for Education in Tajikistan: Ministry of Education and World Bank

|

Theme |

MOE Priority |

WB Priority |

|

Absolute Insufficient Number of Textbooks |

1 |

4 |

|

Affordability of Textbooks |

2 |

5 |

|

Changes in Aims of Content and Type of Pedagogy |

5 |

1 |

|

Changes in Management and Financing |

6 |

2 |

|

Changes in Teacher Knowledge and Teaching Methods |

7 |

3 |

|

Preparation of Textbooks in Tajik and other Languages |

3 |

- |

|

Preparation of Textbooks in the Humanities |

4 |

- |

The issue of developing basic ability to read and write is a priority for the Tajik authorities, who fear a whole generation may have reduced levels of literacy compared to the generation before. Thus, no new conception of literacy is involved in government’s concerns: the authorities are concerned to re-establish and maintain previously achieved literacy standards. The World Bank seems to wish to change the notion of literacy and numeracy developed in school,[16] to be in line with new conceptions in the corporate world of what it means to be literate, that Street has called the “New Work Order”.[17] Differences in conception of necessary reforms between responsible government authorities, whose ability to implement changes are limited, and funding agencies with relatively unlimited funds may have a significant effect on the direction of education in Tajikistan.[18]

LANGUAGES OF

TAJIKISTAN

THE MAJORITY LANGUAGE

Tajik

Tajik is the form of Persian spoken in Central Asia, and is spoken by large numbers of people in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Literary Tajik is based on the northwestern dialect spoken in Uzbekistan and the neighbouring parts of Tajikistan, using the language of Samarqand in Uzbekistan as the standard. Hundreds of years of Tajik/Uzbek bilingualism in the northwestern dialect zone has had a great influence on this dialect. The southern dialects of Tajik are spoken in the more mountainous parts of Tajikistan bordering on Afghanistan, and resemble the form of Persian spoken in Afghanistan, Dari. Tajik differs from other varieties of Persian in the large quantity of Turkic and Russian vocabulary it has borrowed, and the choice of script: changing from Arabic to Latin in the 1920s, and from Latin to Cyrillic script in the late 1930s.[19] The percentage of Tajiks in the population is estimated at 62.2% in 1989, with the number that speaks Tajik as a first language estimated at 3,344,720.[20]

MINORITY LANGUAGES

Turkic

languages: Uzbek and Kyrgyz

Uzbek is the

language of the majority of the population of Uzbekistan, and of a large

minority of the population of Tajikistan. In some districts, Uzbek speakers

form a local majority, while in others their numbers are less concentrated.

Kyrgyz is the language of the majority of the population of Kyrgyzstan, and of

a local majority of the population of Murgab district in the Pamir plateau of

Tajikistan.[21] The respective percentages of Uzbeks and

Kyrgyz in the population is estimated at 23-24% and 1.3%, while the number who

speak Uzbek and Kyrgyz as first languages is estimated as 873,000 and 64,000

respectively.[22]

East Iranian Languages: Yaghnobi and Pamiri languages

The indigenous languages of

today’s Tajikistan are believed to have been East Iranian languages, distinct

from Persian, a West Iranian language. All that is left of the ancient East

Iranian Soghdian language spoken in the plains of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan is

its descendant, Yaghnobi, spoken in the upper Zeravshan valley of northwestern

Tajikistan by an estimated 2,000 people.[23]

Table 2 below shows estimated numbers of speakers of other East Iranian

languages in Tajikistan, the Pamiri languages of Mountainous Badakhshan

province.[24] The shift

to Tajik has been slower in the Pamir mountains than it has in

Yaghnobi-speaking areas; however, accurate figures are unavailable since the

census in Tajikistan does not measure numbers of speakers of East Iranian

languages, who are counted as Tajiks by nationality.[25]

Table 2

Speakers of East Iranian Pamiri Languages in Tajikistan

|

|

Language |

Estimated No. of Speakers 1939/1940 |

Estimated No. of Speakers 2001 |

|

1. |

Yazgulami |

2,000 |

3-4,000 |

|

2. |

Rushani |

5,300 |

|

|

3. |

Bartangi |

3,700 |

|

|

4. |

Shugni |

18,600 |

|

|

|

Total Shugni Group: 2+3+4 |

27,600 |

40,000 |

|

5. |

Ishkashimi |

|

3-4,000 |

|

6. |

Wakhi |

4,500 |

20,000 |

Other Minority Languages

There are many other small minority languages of Tajikistan. Some of them have a greater number of estimated speakers than some of the East Iranian minority languages, but are frequently not spoken in a compact territory, as the East Iranian languages are. Table 3 below shows estimated numbers of speakers of the remaining minority languages of Tajikistan.[26] The estimated number of native speakers of Russian and Ukrainian is large: ethnic Russians were estimated as making up 8% of the total population of Tajikistan and 32.8% of the population of the capital city Dushanbe before independence, but has gone down since independence and the civil war.[27]

Table

3

Speakers of other Minority Languages in Tajikistan

|

Language |

Est. No. of Speakers |

Language |

Est. No. of Speakers |

|

Uyghur |

3,581 |

Kazakh |

9,606 |

|

Pashto |

4,000 |

Korean |

13,000 |

|

Balochi |

4,842 |

Turkmen |

13,991 |

|

Bashkir |

5,412 |

Ukrainian |

41,000 |

|

Armenian |

6,000 |

Tatar |

80,000 |

|

Ossetian |

8,000 |

Russian |

237,000 |

Languages of “Wider Communication”: Russian and English

Russian is also widely known as an additional language in Tajikistan.

Despite the falling number of ethnic Russians, and its declining prestige,

Russian still has a high status. Many official government documents are

produced in Russian rather than Tajik. Although the Law “On Language”

stipulates that Tajik is the official state language, it is expected to take

some time to implement full conversion to Tajik as the language of the state.[28] Russian language media are still widely

available, and Russian-medium education programs are not attended only by

children who are ethnic Russians.[29] Recently, English has overtaken Russian in

popularity, since salaried employment with government and international

agencies now seems to depend far more on English proficiency than on Russian

proficiency.[30]

LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN

The

legal policies on language in independent Tajikistan are somewhat complex,

since the Constitution, the Language Law, and the Education Law, as well as an

official commission of the government on the implementation of the language law

all make normative statements on the use of language in Tajikistan. The pre-independence Language Law of 1989

declared Tajik to be the official language of Tajikistan, while guaranteeing

the free use of minority languages, including East Iranian languages.[31]

The constitution of the independent

Republic of Tajikistan Article 2 similarly states, “The state language of

Tajikistan is Tajik. Russian is a language of inter-ethnic communication. All

nations and peoples residing on the territory of the republic have the right to

use freely their native languages”,[32]

but did not specifically include speakers of East Iranian languages, who are

not considered to be a national group separate from the Tajik ethnicity.[33]

However, in 1993, the Law on Education had

been decreed, Articles 5 and 6 of which made Tajik the language of instruction,

while permitting instruction to be given in other languages in ‘compact

settlements of minority groups’.[34]

Later, in 1997, the Dodkhudoeva Commission’s report on Implementation of the

1989 Language Law was adopted recommending that Tajik be taught in all schools,

no matter what the main medium of instruction and that Kyrgyz, Uzbek and East

Iranian languages should receive special consideration in areas where there are

concentrations of speakers of these languages. Instruction in their own

language together with Tajik was guaranteed at the elementary school level for

children whose mother tongue was one of the East Iranian languages.[35]

According to the Education for All 2000

Report prepared by the Tajikistan authorities, the education system of

Tajikistan is based on the ‘national school’, where children are educated in

the language of their nationality providing that there are sufficient numbers

to provide schooling for that nationality.

One of the great concerns mentioned in this report is the need to

develop curricula, prepare textbooks and train teachers not only for

Tajik-medium schools. In practice, this right is extended to members of three

‘titular nations’ of Central Asia; i.e., to Uzbeks (Uzbekistan), Kyrgyz

(Kyrgyzstan) and Turkmens (Turkmenistan).[36]

The need to develop curricula, textbooks and teachers for such schools is not

mentioned in the Education for All Report, although the Commission on

Implementation of the Language Law recommended that the right to primary

education in the native language be guaranteed for speakers of East Iranian

languages.[37]

Thus, there is an ambiguity in policy on the use of minority languages as media of instruction in schools. Free use in Tajikistan is not guaranteed by the constitution to languages or to individuals but to social groups: nations or peoples. However, the interpretation of nations or peoples may be limited in practice.

BILINGUALISM,

MULTILINGUALISM AND EDUCATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN

In practice in

Tajikistan, there are different types of bi- and multilingualism. One type

would be bilingualism developed through interpersonal contact, and another type

would be developed through schooling.

In areas of mixed population, with large numbers of different

nationalities living nearby, it is quite natural to learn at least basic

proficiency in the language used by your neighbours. Thus, in the parts of

Uzbekistan with mixed Tajik-Uzbek populations, Tajik-Uzbek bilingualism has

gone on for centuries, and has resulted in the popular dialects of Tajik and

Uzbek influencing each other strongly, with lexical, morphological and

syntactic borrowing in both directions.[38] Similarly, Kyrgyz-Wakhi bilingualism is

reported in Mountainous Badakhshan[39]

and bilingualism is reported between Shugni, the Pamiri language with the

greatest number of speakers and the language of the provincial centre Khorog,

and other Pamiri languages.[40]

Another type of bi- or multilingualism is school-based. In the

past many Central Asians would send their children to Russian language schools,

in order to provide them with a higher proficiency in the highest status

language, and a better quality of education in general. In today’s environment,

some minorities select Tajik-medium schools, since Tajik has higher status than

other languages in Tajikistan except Russian and English. In Murgab district on the high Pamir plateau

in Mountainous Badakhshan province, Kyrgyz parents are sending their children

to Tajik-medium schools rather than Kyrgyz-medium schools, because the quality

of education is seen to be better.[41]

Nevertheless, this kind of bilingualism is not developed through bilingual

education; rather, one language is used as exclusive medium of instruction for

all subjects with the second language being taught as a school subject. However, true bilingual education is now

available in a limited number of schools in Tajikistan.[42]

TYPES OF

LANGUAGE USE AND LITERACY IN MULTILINGUAL SOCIETIES

One theoretical distinction useful in understanding the educational difficulties of minority-language children is the division of language proficiency into two types:

Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills, or BICS, and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, or CALP.[43] Another useful distinction is that of register.[44] Corson points out that differences between registers can be great, for example, the bulk of the lexicon of academic English is of Latin or Greek origin, and does not use common English roots or affixes.[45] Nevertheless, the registers in English are mainly distinguished lexically, with syntax and phonology not differing radically. When the differences between registers used in a society involve so many changes in lexis, morphology, syntax and phonology that they are virtually different languages, the situation is called diglossia.[46] A question that has been little studied in Tajikistan is the difference between varieties of Tajik. The language of schooling in Tajikistan is literary Tajik, which is based on the classical Tajik language of Samarqand and Bukhara (in today’s Uzbekistan). Since developing CALP in Tajik-medium schools depends on mastering literary Tajik based on northern dialects, for children in southern dialect areas, the gap between BICS proficiency and the language of schooling would be more than it would be for children in northern dialect areas, and even more so for speakers of East Iranian languages schooled in Tajik, a second language for them. In areas of high levels of Tajik-Uzbek bilingualism, grammar and vocabulary of informal spoken Uzbek and Tajik are influencing each other and diverging from their respective literary standard.[47]

ADDITIVE AND SUBTRACTIVE BILINGUALISM

Different types of bilingualism can be distinguished according to the relationship between first and second languages. Additive bilingualism provides additional abilities or skills to the learner, and does not involve the new language and associated culture replacing learners’ first language and culture. Subtractive bilingualism involves the second language performing certain communicative functions instead of the first language. Under subtractive conditions, speakers of minority languages may feel pressured to give up their language and culture to conform to the majority, or may resist learning the second language and participating in education as a means of preserving minority group language and values.[48]

Studies have found that spending time on mother tongue education in bilingual education programs does not necessarily lead to reduced academic performance in the state language.[49] The BICS/CALP distinction implies that minority language children require support in learning the type of language proficiency (CALP) that is necessary for the development of proficiency in the state language. Thus, introduction of instruction and testing in the second language before sufficient development of proficiency in that language (both BICS and CALP) may lead to difficulties either in learning subject matter, or in demonstrating learning in a second language. The interdependence hypothesis may also imply that development of second language proficiency may be restricted if the second language is used to replace the first language in the classroom, or if the second language is introduced before first language proficiency is sufficiently well developed to permit decontextualized learning.[50]

SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING METHODOLOGIES:

Second Language as a School

Subject, Submersion/Immersion in the Second Language,

Transitional

Bilingual Education and Maintenance Bilingual Education

There are many ways for young

people whose mother tongue is not the official language of the country to be

accommodated by an education system. The first choice is to be educated in the

mother tongue, and to study the official language as a school subject. In this

case, the second language is not a medium of instruction for other subjects.

This is the case for children in the National schools of Tajikistan,

whose first language is the medium of instruction. Submersion instruction for minority-language children

implies exclusive use of children’s second language as medium of instruction,

with no instruction in the first language, and in school with no special

support for their linguistic needs. Submersion has been criticized as leading

to subtractive bilingualism.[51] Transitional Bilingual Education

typically provides bilingual instruction for primary instruction, and is

designed to ease the transition into exclusive use of the second language in

school for post-primary education. Maintenance

Bilingual Education is designed to develop full literacy in both the minority

and majority language, and to assist in the maintenance of minority languages

under pressure for minority language communities

to shift to the majority language.[52]

LANGUAGE AND

LITERACY DEVELOPMENT IN TAJIKISTAN

Thus, in Tajikistan, there are many kinds and levels of bilingualism. In the Soviet era, bilingualism in the “mother tongue” and Russian was highly valued.[53] However, we have seen that this has often led to subtractive bilingualism in the sense that those educated by means of submersion in the Russian language did not often acquire academic proficiency in their mother tongue. Thus, a diglossic situation was created where Russian was used as the High language used for academic, technical, and official purposes (CALP) with the native languages reserved for informal conversational unofficial situations (BICS). However, reports suggest that the bilingualism achieved in local language and Russian was subtractive bilingualism, or diglossia, rather than additive bilingualism. Instead of Central Asians becoming highly literate and developing BICS and CALP proficiency equally well in both languages, BICS and CALP proficiency tended to be developed in Russian among Central Asians who attended Russian-medium school. As Schulter noted in Kyrgyzstan many of the urban Kyrgyz élite are sufficiently Russified as to not be able to speak Kyrgyz. Since independence, the Law on Language has attempted to require and promote the use of Tajik for all the functions formerly played by Russian. This is problematic for those Tajikistanis whose first language is not Tajik, and whose Tajik proficiency may be substantially less than their Russian proficiency.

Figure 2

Geographic Distribution of Ethnic Groups

in Central Asia

Source:

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/middle_east_and_asia/casia_ethnic_93.jpg

Although there are many ethnic and linguistic groups in Tajikistan, there are some areas that are quite ethnically mixed, and others where one ethnic group is in the majority (See Figure 2 above). There are many areas in lowland Tajikistan, where ethnic Tajiks and the Tajik language as first language (L1) are in the majority. In these areas children will be attending Tajik-medium school, and study Russian or English as second or third languages in later years of school. Note that in Tajik-medium schools, no other language of Tajikistan, such as Uzbek or Kyrgyz, is studied as a second language (L2).

There are other areas where a non-Tajik ethnicity is in the majority, for example in parts of Khatlon province in southern Tajikistan, and parts of Leninabod province, where Uzbek-speakers are in the majority, and parts of Mountainous Badakhshan province where Kyrgyz-speakers are a local majority. In these areas children will be attending school with their native language as medium of instruction, and study Tajik as a second language, and possibly Russian or English as third languages.[54]

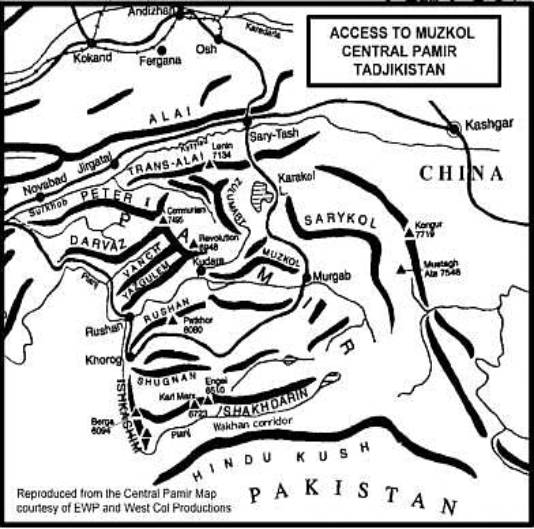

Figure 3

Valleys and Languages of Pamirs[55]

retrieved 10-9-2003 from http://www.ewpnet.com/muzkol.jpg

Speakers of East Iranian languages are special cases. In these areas, children are considered to be ethnically Tajik, and so attend Tajik-medium school. Primary education in East Iranian languages is guaranteed by law, but there are many problems in implementation of mother tongue education for these children.[56] Yagnobi speakers live in isolated villages in the upper reaches of the Zeravshan river in Leninabod province surrounded by Tajik-speakers in neighbouring villages. Thus, there should be opportunities for Yagnobi-speaking children to develop BICS proficiency through interaction with Tajik speakers. Speakers of Pamiri languages are more numerous than Yagnobi speakers, and are cut off from Tajik-speaking areas, and so children in these areas will have little opportunity to develop BICS proficiency in Tajik through interaction.

However, there are many opportunities to develop BICS in languages other than Tajik through interaction in the Pamirs. Each Pamiri language is spoken in an area contiguous to another Pamiri language, and in the case of Wakhi, contiguous to Kyrgyz as well (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 above). The provincial centre Khorog is in the centre of the Shugni-speaking district. Thus, growing up in the Pamirs, children can be exposed to the Pamiri language of contiguous valleys, and to Shugni in the provincial centre. It is apparently quite common to be able to speak more than one language learned informally outside school.[57] Tajik speakers attend Tajik-medium school and develop CALP through their L1. Speakers of East Iranian languages attend Tajik-medium school and develop CALP through their L2, Tajik. Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Russian speakers attend L1-medium school and should develop CALP through their L1.

FRAMEWORKS FOR THE STUDY OF BI- AND MULTILINGUAL SOCIETIES:

THE ETHNOGRAPHY OF COMMUNICATION AND CONTINUA OF BILITERACY

Ethnographic

studies in communication have developed frameworks for the observation and

analysis of language use in the field. Dell Hymes[58]

proposed the acronym SPEAKING as a mnemonic for significant factors to observe:

Setting

/ scene

Participants

Ends (expected outcomes and latent

goals)

Act

(message form and content),

Key

(tone and manner)

Instrumentalities

(Channels and forms- language, dialect, variety, code, style)

Norms

(interaction and interpretation)

Genres

(poem, myth, talk, lecture, prayer etc).

Hymes’

methodology was used in the field by Nancy Hornberger in her fieldwork on

Spanish-Quechua language choice, bilingualism and biliteracy among the Quechua

people of the mountains of Peru.[59] Using such a framework, Hornberger observed

that use of Spanish or Quechua could be described by domain: situations of

setting and relationship of speakers that were associated with one language

choice rather than another.[60]

In lowland Peru, Spanish monolingualism is the norm; in highland Peru, the

indigenous population is generally schooled in Spanish, and acquires varying

levels of bilingualism in Spanish. Advancement in the school system normally entails

acquisition of Spanish, and incomplete development of proficiency in Quechua.

Hornberger was interested in the question of whether the type of schooling,

Spanish-medium or bilingual Quechua-Spanish, would affect the use and

maintenance of Quechua. Hornberger observed and compared language use of

students who were all native speakers of the Quechua in two schools: a

traditional Spanish-medium school,[61]

and a bilingual school where both Spanish and Quechua were media of

instruction. With this methodology, complex patterns of language choice can be

observed, and inferences about the factors influencing language choice can be

made. Thus, if policy seeks to promote language maintenance of minority

languages, or improved levels of literacy in the majority language among

speakers of minority languages, such a participant observer methodology may

give valuable insight into the effectiveness of policy choices in practice.[62]

Hornberger

has recently refined the methodology to include what she calls “Continua of Biliteracy”,

[63]

which include more information than the “Speaking” in the observation format:

Contexts, Development, Content and Media of Bi/Multiliteracy, with each of the

above 4 continua having three possible values. This refinement allows even

finer details of the circumstances of language use to be recorded, allowing

subtle factors influencing language choice to be identified.

LANGUAGE CHOICE IN SCHOOLS IN

MOUNTAINOUS BADAKHSHAN, TAJIKISTAN

Language choice in Tajikistan can be even more complex than in Peru. In Khatlon province, for example, Standard Tajik, Southern dialect of Tajik, Pamiri languages, Uzbek and Russian are used. Thus, the study of language choice, multilingualism and multiliteracy are all of intrinsic interest in Tajikistan, but also of use for education policy makers. However, as yet, there is little research on this question in Central Asia.[64]

Niyozov conducted a comparative case study of two teachers in two different Tajik-medium schools in Mountainous Badakhshan, Tajikistan. The methodology of the study was participant observation of classes together with follow-up interviews with teachers observed and focus group discussions with teachers and administrators in the schools observed. Notes were taken during observed classes, interviews and focus groups, which were also taped, transcribed and selectively translated into English. Although it was not the purpose of the study to observe language switching and literacy practices, the role of language for teachers of Pamiri languages in the nominally Tajik-medium school in the Pamir Mountains continually entered into observations, and allows an interpretation of Niyozov’s data using Hornberger’s framework of analysis to determine language use in the classroom and associated factors. The findings are quite similar to Hornberger’s study of the traditional school in Peru.

Secondary school history was taught in Tajik using Tajik textbooks. The teacher claimed that students learning suffered due to problems with their second language, Tajik. Some students’ Tajik proficiency is insufficient to comprehend lessons adequately,[65] especially since the curricula and texts are too abstract for comprehension in their second language.[66] Weak expressive ability in Tajik makes some unable to express their understanding clearly,[67] causing them to receive lower marks and to feel reluctant to speak in class due to anxiety about ridicule from peers, criticism from teachers and lower marks,[68] especially since assessment in the Soviet tradition is done orally in front of the class on a frequent basis.[69]

This teacher’s in-class practice is similar to the traditional teachers observed in Peru: when the textbook language is difficult, she either simplifies the standard Tajik of the curriculum to make it more comprehensible, or provides supplementary explanation in Shugni.[70] Nevertheless, this teacher is well aware of the ‘ideological’ factors[71] involved in questions of language choice, and attempts to increase the use of Shugni through involvement of the community in non-formal educational activities. As in Peru, the teacher feels the school to be the domain of the official language, Tajik, and although the teacher is a native speaker of Shugni, the students’ native language, she is reluctant to teach in Shugni in the school. However, this teacher feels more comfortable using local language for learning through extracurricular activities, such as during a non-formal history lesson outside class, listening to a village elder talk about his experiences in World War II. Yet despite the teacher’s reflectiveness on language, literacy and learning, the local language is rarely used in the actual classroom for fear of being criticized by authorities or parents, except to resolve communication failures and discipline students. Nor is learning in the local language extended to the written mode, as is done in the bilingual schools in Peru, done or even considered.[72]

IMPLICATIONS OF NIYOZOV’S STUDY FOR LITERACY DEVELOPMENT IN TAJIKISTAN

The teacher’s comments on the difficulty of many of her high school students in dealing with formal academic lessons in their second language, Tajik, are provocative. The students have learned Tajik so far either through Submersion, or Transitional Bilingual Education, rather than through Maintenance Bilingual Education. At the same time, they have had little opportunity to develop BICS skills through interaction with Tajik-speakers, and little or no opportunity to develop CALP skills in their first language, since the proposed bilingual education program is for the first 4 years of school only, and possibly less where this program is not actually implemented. In such an environment, it is to be expected that many students will develop insufficient Tajik-language proficiency to succeed in a Tajik-medium school system.

Similarly, the Interdependence Hypothesis would predict that high levels of second language BICS and CALP skills would be able develop in students, who either had the opportunity to develop and maintain CALP as well as BICS in their first language, while gradually developing CALP proficiency in the second language, as would be the case if a well-designed Bilingual Maintenance Program were in place. The Threshold Hypothesis[73] also predicts that those Shugni speakers who are exposed to oral interaction in Tajik, and written material in Tajik outside school, perhaps in the home, and who also continued development of literacy in Shugni, would develop higher levels of proficiency in Tajik skills, both BICS and CALP, with possible benefits for cognitive development and school achievement.

It is a paradox that while teachers complain about the poor achievement of Pamiri students due to weak Tajik proficiency, Pamiri intellectuals are proud of the academic achievements of students from their region and state that speakers of Pamiri languages are over-represented in universities in Tajikistan.[74] If it is actually true that higher proportions of post-secondary students are from the Pamir Mountains, it would be interesting to study the experience of such individuals, to identify factors that influence their academic achievement. Research suggests that development of bilingualism under additive circumstances is associated with benefits to cognitive development and academic achievement.[75] However, in the past much higher education was conducted in Russian-medium. It would be interesting to study the relation between degree and type of bi and multilingualism and academic achievement. Some Pamiris have developed BICS proficiency in one or more local languages, as well as Tajik and Russian, and CALP proficiency in two languages, Russian and Tajik.[76]

THE

STUDY OF MULTILINGUALISM, MULTILITERACY AND EDUCATION IN TAJIKISTAN

Street juxtaposes what he calls the ‘autonomous’ approach to the study of literacy and the ‘ideological’ approach. He critiques the autonomous approach for treating literacy as if it were isolated from social factors affecting use, and as if it were isolated from oral use of language, or isolated from registers other than those associated with schooling. He proposes instead an ethnographic approach which takes into account all of the factors that he feels the autonomous approach neglects.[77]

However, at the moment, literacy in Tajikistan is not being studied through either of these approaches. Information on literacy levels of school-aged youth and young adults in the aftermath of the civil war is not readily available in English, and may not be available in Tajik. In a review of the literature in English available on education in contemporary Tajikistan, data on achievement are not apparent. The only empirical measure available in the UNICEF and UNESCO reports cited above are on levels of registration of children in school, with no data given on attendance or achievement.[78]

Studies of the relation between such factors as educational attainment of parents, occupation of parents, district of residence of students, language used in the home, number of languages spoken by family members, can be relatively easily gathered through the school system using a survey methodology. In addition, data on the language of textbooks and instruction can be gathered. A study of language variables influencing school participation and achievement in selected regions of Tajikistan could be conducted through survey methodology and statistical analysis of survey results to examine the interrelationship of language, literacy and education.

APPLICATION OF CONTINUA OF BILITERACY AS A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDYING LANGUAGE AND

LITERACY IN TAJIKISTAN:

Minority-Language

Students in a Tajik-medium Classroom in Mountainous Badakhshan Province

Nancy Hornberger (2000, 2002) has attempted to devise a framework that allows for such detailed observation of the contexts of literacy in the sense that Street proposes.[79] Niyozov’s study includes data on language use between teacher and students, but does not include data on teacher-teacher language use, home language use, or language use in public. Applying the framework to the classroom observed by Niyozov allows us to look at the complexity of language use observed here in a systematic way.

The first continuum is the Context of Biliteracy continuum, which includes three scales: micro-macro context, oral-literate use, and multi-monolingual use. Applying the Contexts of Biliteracy to the classroom observed by Niyozov, we find on the micro-macro context scale that the micro-context of the classroom is bilingual Shugni-Tajik while the macro-context of the educational system is monolingual Tajik; on the oral-literate scale, we find that Shugni is exclusively used orally, while literate uses of language are reserved for Tajik; while on the multilingual–monolingual scale, the classroom is weakly bilingual: mainly Tajik is used with occasional shifts into Shugni.

The second continuum is the Literacy Development continuum, which includes two scales: receptive-productive language use and oral-written language use. Students engage more in receptive language use, listening to the teacher and reading, with relatively little time devoted to oral discussion or writing of learners’ understandings and ideas. While little opportunity for development of productive language use is provided, educational achievement is assessed via oral production. Reading, writing and most listening are done in the second language, Tajik, yet outside the classroom opportunities for receptive or productive use of Tajik are few.

The third continuum is the Content of Biliteracy continuum, which in the classroom consists of: national minority language speakers learning the national majority language, who are in fact local majority speakers learning a virtually “minority’ language, since almost no locals speak Tajik as a first language. The language of the classroom is literary national majority language and vernacular local language with the literary language relatively decontextualized and the vernacular highly contextualized.

The fourth continuum is the Media of Biliteracy continuum, which in the classroom consists of simultaneous exposure to national majority literary language and local oral vernacular language often used to translate or explain difficult concepts expressed in the literary language. The two languages used have different structures in that they are mutually incomprehensible languages. However, they do have a family resemblance such that there ought to be some ease of transfer from Shugni to Tajik. The script for Shugni is quite similar to Tajik script, using Tajik Cyrillic letters with extra sounds represented by Tajik letters adapted with diacritic marks. This would be a factor in early acquisition of decoding skills in Tajik, if Pamiri-speaking children were taught literacy in this script, which often they are not. A key factor affecting the language learning situation and the amount and type of development of multilingualism, is access to exposure to language in the mass media: newspapers, magazines, books, radio and television. The Pamir region is isolated from lowland Tajikistan: newspapers from the capital or other regions and recently-published books in Tajik are not widely available. Radio and television do penetrate the mountains. The greater availability of Russian media, and the continued high status of Russian may lead to greater development of Russian than Tajik proficiency.[80]

Minority-Language

Students in National Schools in Lowland Tajikistan

Mountainous Badakhshan is not the only case in Tajikistan in which study of language use at home, school and in the wider society has implications for the education of youth and the development of literacy. First, there is the question of literacy development in the national schools. For students enrolled in national schools where Tajik is not the medium of instruction, it is important to develop high levels of literacy in their first language as well as in Tajik that are similar to those of students in Tajik-medium schools. While the education system in general suffers from a lack of textbooks, the shortage is even more acute in Uzbek and Kyrgyz–medium schools.[81] Already there are reports, for example, that Kyrgyz-speaking children are being enrolled in Tajik-medium schools rather than in Kyrgyz schools, since the quality of education is considered to be lower in Kyrgyz than Tajik-medium schools.[82] There is a risk that literacy levels of students enrolled in Uzbek and Kyrgyz–medium national schools will be lower than in the past, given the shortage of materials and instructors in minority languages. At the same time the importance for speakers of minority languages of developing literacy in Tajik has increased since the fall of the USSR. Those who live in ethnically-mixed areas may have the chance to develop BICS proficiency in Tajik through interaction, but the amount of instruction in literary Tajik school and of exposure to this form of language, in and out of school, may not be sufficient for students who are speakers of minority languages to develop CALP proficiency in the state language.

CONCLUSION

Although Hornberger’s system of continua is primarily a descriptive tool, it can provide a method for dealing with the richness and complexity of the linguistic situation in Tajikistan. Yet in the present circumstances, little research in this area is being done in Tajikistan. There is a practical need for researching language, literacy, education and related questions. Such questions need to be studied to better inform policy development to ensure language maintenance of the minority languages of Tajikistan, and increased educational attainment, and inter-regional and interethnic harmony for all citizens of Tajikistan. Researchers and policy makers must tread carefully, for to do nothing could waste the potential of many of Tajikistan’s youth, while to do the wrong thing would be wasteful of precious resources, and possibly harmful to social harmony. The above-mentioned introduction of bilingual education may be a positive step; but the experiment is being piloted in the richest province, where damage from the war was the least, and still requires major financial inputs from outside donors; Tajikistan needs an approach to curriculum that can promote literacy development in both first and second languages in a sustainable way.

Non-Formal Education and

Literacy Development

An interesting group of projects in non-formal education has been having great success with some of the most marginal youth in the world: poor, rural girls in developing countries. The Escuela Nueva program in rural Colombia, the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) schools of rural Bangladesh, and the UNICEF Community Schools of Upper Egypt have all increased attendance, reduced dropout and improved achievement among their students.[83] Farrell has made an analysis of similarities among the three systems and identified common features, several of which relate to language in education.[84] All of the programs teach using their own guidelines, preparing their own innovative materials, which involve far less teacher-centred instruction, and engage students more in the active construction of knowledge through student-student and teacher-student interaction than does the typical methodology. Teachers are trained using the same student-centred interactive methods they are expected to use, and are given many opportunities to observe successful teachers in model classrooms, and much support from experienced teachers and supervisors.

Another

interesting commonality among the programs is the enormous emphasis on rich

language experience in contrast to standard methodology in each of the

countries. Teachers interact with students and negotiate meaning, and teach

some subjects through whole-class discussion; students discuss in multi-age

groups what activities to select, carry them out, and then discuss what has

been learned in preparation to write a group report of what they did, why they

did it, and what they learned.

Anecdotal reports suggest children in these programs develop literacy

highly in the fullest sense: they are good listeners, readers, confident

writers and speakers with relatively highly developed critical thinking and

problem-solving skills, when compared with children in standard schools. In

cases where students in non-formal schools have been required to take

standardized state achievement tests, performance has been similar to or

slightly above scores in traditional schools.[85]

Although

case studies of such non-formal programs have been conducted, none have taken

an ethnographical perspective on literacy. A conceptual framework such as

Hornberger’s Continua of Literacy would be a suitable one to identify the

literacy and multiliteracy practices in effective programs in developing

countries such as these, as a first step to attempt to identify what elements

of classroom literacy practice may be leading to literacy development, and

which might hold lessons for effective, sustainable, local design of

curriculum, and development of pedagogy. As one of the most ethnically and

linguistically diverse nations of Central Asia, Tajikistan can benefit from

some of the approaches towards multilingualism, literacy and education that

have been tried successfully elsewhere. There is also a need for greater

domestic research in these fields by Tajikistan’s scholars in order for their

policy decisions in education to reflect the linguistic diversity and language

needs of Tajikistan’s citizens and children.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aga

Khan Foundation. Report. AKF

Activities in Tajikistan. 2002. (29 July, 2003) http://www.akdn.org/akf/tajikrep_02.pdf

Bahry, Stephen A. Travelling

Policy and Local Spaces in the Republic of Tajikistan: a comparison of the attitudes of Tajikistan and the World Bank

towards

textbook provision. European Education Research Journal, Volume 4, Number 1.

Baker, Colin. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon, U.K.: Multilingual Matters, 1996.

Bashiri, Iraj (1997). The Languages of Tajikistan in Perspective. Available at http://www.iles.umn.edu/faculty/bashiri/Tajling%20folder/Tajling.html

------ (1998). Tajik Ethnicity in Historical Perspective. Available at http://www.angelfire.com/rnb/bashiri/Ethnicity/Ethnic.html

Bransten, Jeremy . “Central

Asia: As World Marks Literacy Day, What of USSR’s legacy?” Eurasian Insight

Sept 9, 2003.

Available at http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insight/articles/eav090703a.shtml.

Corson, David . “The Learning and Use of Academic English Words.” Language Learning 47:4 (1997): 671-718.

Cummins, James. “Linguistic Interdependence and the Educational Development of Bilingual Children.” Review of Educational Research 49 (1979): 222-251.

------ “Age on Arrival and Immigrant Second Language Learning in Canada: A Reassessment.” Applied Linguistics 1 (1981): 132-149.

------ “Empowering Minority Students: a framework for intervention.” Harvard Education Review 15 (1981): 18-36.

------ Language, Power and

Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon, U.K.: Multilingual

Matters, 2000.

Dodykhudoeva, Leila. “The sociolinguistic situation and language policy of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan: The Case of the North Pamir

Languages”. Paper presented at

CELEUROPA Conference on Sociolinguistics and Language Planning, St. Ulrich,

Switzerland, December 12-14, 2002.

http://www.geocities.com/celeuropa/AlpesEuropa/Urtijei2002/Dodykhudoeva.html

Drake, Earl. “World Bank Transfer of Technology and Ideas to India and

China.” In Knowledge Across Cultures: A

Contribution to Dialogue Among Civilizations, edited by Ruth Hayhoe

& Julia Pan, 215- 228. Hong Kong:

Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong, 2001.

Eurasia Foundation Press Release (2004). “Group of Schools Selected in

Eurasia Foundation, Netherlands

Embassy-Funded Ferghana Valley

Multilingual

Education Project”. 19, March, 2004. Osh,

Kyrgyzstan: The Eurasia Foundation. (18 May, 2004)

http://www.efcentralasia.org/Press

Releases/PRKRO_Mar192004_eng(CIMERA).pdf

Ethnologue. Languages of Tajikistan. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=Tajikistan

Farrell, Joseph P. The Egyptian Community Schools Program: Case Study. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto, 2003.

------ “ Alternative Pedagogies and Learning in Alternative Schooling Systems in Developing Countries: A Comparative Analysis”. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Comparative and International Education Society, Salt Lake City, USA, March, 2004.

Haiplik, Brenda. BRAC’s Non-Formal Primary Education (NFPE) Program. Draft Case Study. Toronto: Academy for Educational Development,

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, 2004.

Holmes, B., G.H. Read and N.Voskresenskaya. Russian Education: Tradition and Transition. New York: Garland Publishing Inc, 1995.

Hornberger, Nancy H. Bilingual education and Language

Maintenance: A Southern Peruvian Quechua Case.

Providence, Rhode.Island, USA: Foris Publications, 1988.

------ “Revisiting the Continua of Biliteracy:

International and Critical Perspectives.” Language and Education 14:2

(2000): 96-122.

------ “Multilingual Language Policies and the

Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Approach.” Language Policy 1 (2002): 27-51.

Hymes, Dell. “Towards Ethnographies of Communication.” In Language

and Literacy in Social Practice, edited by J. Maybin, 11-22.

Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1994.

Landau, Jacob M. and Barbara Kellner-Heinkele. Politics of Language in the Ex-Soviet Muslim States. London: Hurst and Co, 2001.

Lewis, E. Glyn. Multilingualism in the Soviet Union. The Hague: Mouton, 1972.

Lovell, C. and K. Fatema. The BRAC Non-Formal Primary Education Program in Bangladesh. New York: UNICEF, 1989.

Margus K., I. Tönurist, L. Vabaand J. Viikberg. The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Tallin, Estonia: NGO Red Book, 2001.

http://www.eki.ee/books/redbook/pamir_peoples.shtml

McEwan, P. “The Effectiveness of Multigrade Schools in Colombia.” The International Journal of Educational Development 18:6 (1998): 435-452.

Medlin, W.K., W.M. Cave and F. Carpenter. Education and Development in Central Asia: A Case Study on Social Change in Uzbekistan.

Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1971.

Nath, S. K. Sylva and J. Grimes. “Raising Basic Education Levels in Rural Bangladesh: The Impact of a Non-Formal Education Programme.”

International Review of Education 45:1 (1999): 5-26.

Nazarova, Zarina. “Language situation and language policy in

West Pamir”. Paper presented at CELEUROPA Conference on

Sociolinguistics and Language

Planning, St. Ulrich,

Switzerland, December 12-14, 2002. (8 August, 2003) http://www.geocities.com/celeuropa/AlpesEuropa/Urtijei2002/Nazarova.html

Niyozov, Sarfaroz. “Understanding Teaching in Post-Soviet, Rural

Mountainous Tajikistan: Case Studies of

Teachers’ Life and Work.”

Unpublished Ph. D. diss., Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Pitt, J. Case Study for Escuela Nueva Program. Draft Case Study. Toronto: Academy for Educational Development, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education,

University of Toronto, 2004.

Population

Council. The School Environment in Egypt: A Situation Analysis of Public

Preparatory Schools. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo and

Population Council, 2000.

Sarker, S.C. The BRAC Non-Formal Primary Education Program in Bangladesh. Paris: UNESCO, 1994.

Sarmiento Gomez, A. “Equity and

education in Colombia.” In Unequal Schools, Unequal Chances: The Challenges

to Equal Opportunity in the Americas,

edited by F. Reimers, 203-247. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Schiefelbein,

E. “In Search of the School of the XXI Century: Is Colombia’s Escuela Nueva the

Right Pathfinder?” Santiago, Chile:

UNESCO/UNICEF, 1991.

Schlyter, Birgit N. “New Language Laws in Uzbekistan.” Language Problems and Language Planning 22:2 (1998): 143-181.

------ “Sociolinguistic changes in transformed Central Asian societies.” In Languages in a Globalising World, edited by Jacques Maurais and Michael A. Morris,

157-187. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2003.

Schulter, Beatrice. “Language and Identity: The Situation in

Kyrgyzstan and the Role of Pedagogy.”

Paper presented at the

CIMERA Conference on Multilingual

Education

and Mother Tongue Education for National Minorities in Kyrgyzstan, Osh,

Kyrgyzstan, April 15-16, 2003. (20 March 2004)

http://www.cimera.org/en/Publications/ind_conferences.htm

Street, Brian V. “Introduction.” In Cross-cultural Approaches to Literacy, edited by Brian Street, 1-22. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

------ (2001). “Introduction.” In Literacy and Development: Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by Brian Street, 1-18. London: Routledge, 2001.

Sutherland, Jeanne. Schooling in the New Russia: innovation and change, 1984-1995. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

Tajikistan Government. Constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan, 1994. Dushanbe: Tajikistan. Available at http://www.law.tojikiston.com/english/.

UNESCO. The EFA 2000 Assessment Country Report:

Tajikistan. UNESCO, 1999.

Available at http://www2.unesco.org/wef/countryreports/tajikistan/contents.html

World Bank. Priorities and Strategies for Education: a World Bank review. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 1995.

------- (2003). Tajikistan – Education Modernization Project Appraisal Document. April 17, 2003. Available at http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2003/04/29/000012009_20030429171545/Rendered/PDF/25806.pdf