Christian reading cultures

We're so accustomed to understanding Christianity as a religion of the book that it's hard to imagine the character of the Church before it had a canon of Scripture. Presumably the early followers of Jesus shared memories of him and passed on oral traditions. That situation created two problems. First, different communities, even different individuals, no doubt had different memories and traditions, generating conflicts, rivalries, and schisms. And, second, as the people who knew Jesus personally died, subsequent generations wanted sources of authoritative information. The result was a greater emphasis on sacred books authored by Christians.

Now, since early Christians were Jews, and since Jews had sacred texts too, we should probably not assume that a period of oral transmission preceded a period of reading culture. The Church was probably a reading culture from its inception. After all, the letters of Paul were probably read out loud (I Thess. 5:27). But by t he second century, the authority of oral tradition must have waned, in comparison with the sacred texts.

he second century, the authority of oral tradition must have waned, in comparison with the sacred texts.

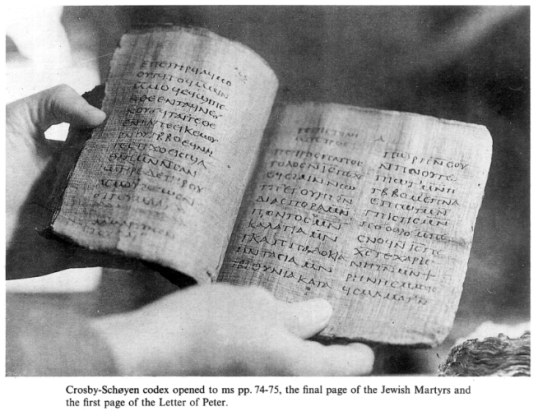

Here's an image of an early codex that includes a Letter of Peter.

In short, early Christian cultures were reading cultures. We have a glimpse of a Sunday service from Justin Martyr's "First Apology," ca. CE 150:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the presider verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the presider in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen.

The early Biblical manuscripts give us physical evidence for the transmission and use of texts in their Christian communities. They are mostly in codex (book) form rather than scroll form, making them easier to handle, hold, transport, read, and browse. Book production required specialized skills of copying, publishing, distributing, and collecting, as well as a certain amount of wealth, suggesting that the Church had a class of trained scribes and librarians. Manuscripts often have markings suggesting cues for public reading, suggesting that the Church had, not just members who were literate, but lectors who were trained to read sacred texts out loud to their community. Surviving non-canonical gospels typically lack these markings; presumably writings without authority were less likely to be read publicly.

All this is the more remarkable given that the great majority of people in the Roman Empire were illiterate. There are indications that Christianity promoted literacy.

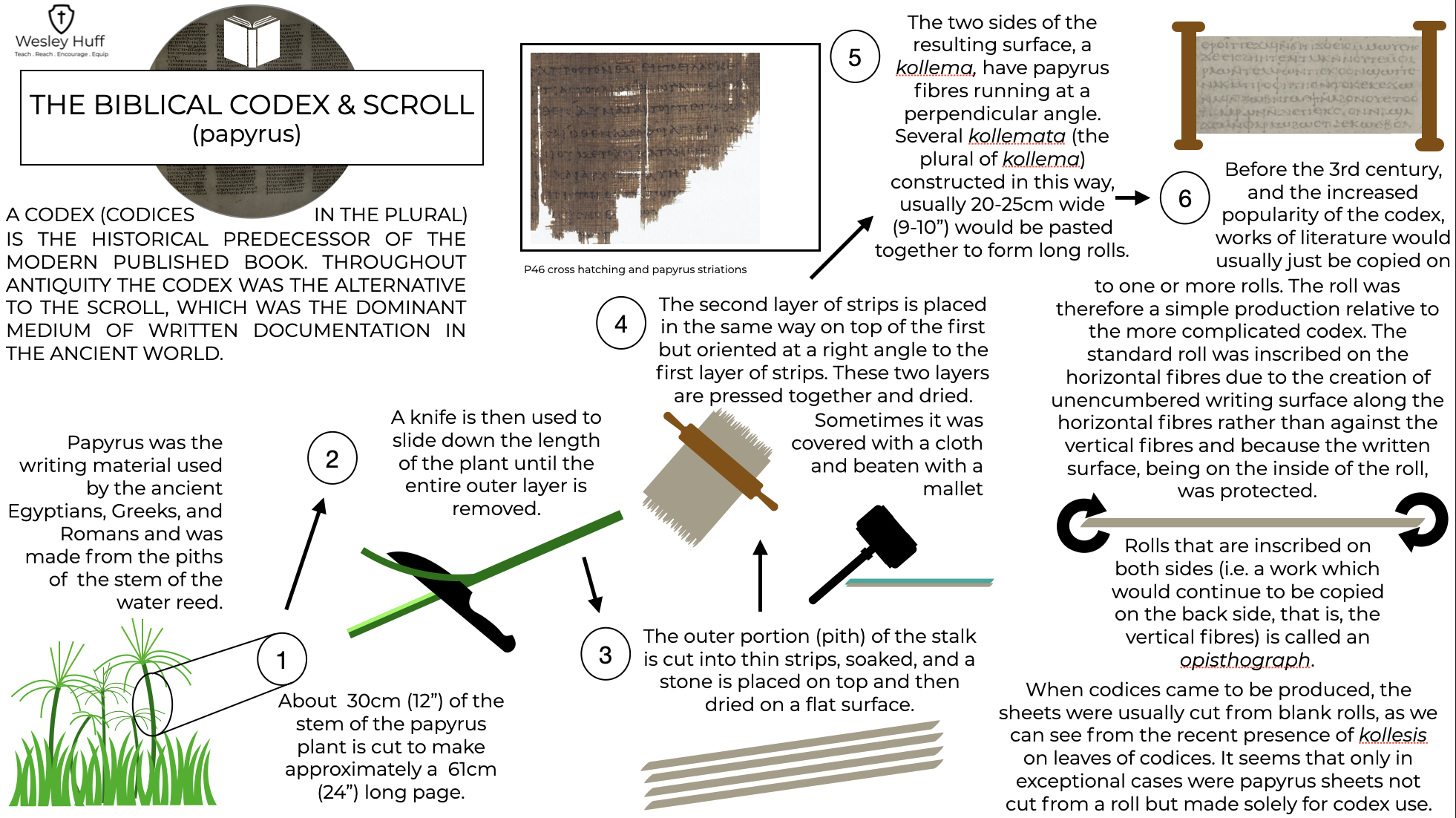

Wesley Huff, a Wycliffe doctoral student working in this area, has produced a number of infographics (see the column to the left) including this introduction to the Biblical papyrus codex. (For a more legible version, visit his infographics site.)

Interpreting Scripture

On Webpage 9 we saw how the Scriptural canon developed. How did people interpret it?

Some issues will be obvious to most people reading Scripture. For instance, when is Jesus speaking literally, and when is he speaking metaphorically? When Jesus says "I am the vine," he clearly isn't identifying himself with a certain botanical species; he's speaking metaphorically. But when he lifts the bread at the last supper and says, "This is my body," many Christians take that as more than a metaphor, and discern the substance of the body of Christ in the eucharistic bread. Did Jesus say "blessed are the poor" (Luke) or "blessed are the poor in spirit" (Matthew)? Did he mean spiritual poverty, economic poverty, or both? Such parallel passages are sometimes inconsistent in their wording.

Alexandria and Antioch

It's a common pedagogical technique in courses on early Christianity to divide early Christian exegesis into two camps or schools, Alexandria and Antioch. It's easy to find arguments for NOT doing so: early exegesis was too diverse and complicated to be reduced to two categories; many writers identified with one camp sometimes wrote as if they belonged to the other camp, and so on. But this paradigm gives us a fairly immediate picture of the diversity of early Christian interpretation, what was at stake, and why it generated theological conversation. It may also help us read Scripture more richly and sensitively.

Alexandria

Alexandria

This is a rendering of the lighthouse at Alexandria, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, in a National Geographic publication.

Alexandria — represented here (in a drawing from the National Geographic website) by its famous lighthouse — was a centre for Jewish Biblical scholarship, as well as pagan literary scholarship, and it became a centre of Christian Biblical scholarship as well. Alexandrian interpreters sought the inner spiritual sense of Scripture. In this course we'll read a Biblical commentary on "the Song of Solomon" by Origen, the greatest Christian teacher of Alexandria. For Origen (as for a long line of Jewish and Christian interpreters until the eighteenth century) the longing of the bride for the groom, and vice versa, reveal the spiritual truth of how we long for God and how God wants to embrace us. Every verse, practically every word of the Song of Solomon yields some deep wisdom for that profound relationship. For Alexandrians, perhaps the main purpose of Scripture is to help us lift up our hearts to God.

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes River (there were other places called Antioch), in what is now Antakya in southernmost Turkey, within dangerous striking distance of modern Syria, was one of the other cultural capitals of the Roman Empire. Its Christian interpreters paid more attention to the clear historical sense of Scripture. In this course we'll look at the commentary of St. John Chrysostom on the raising of Lazarus. He's interested in figuring out the historical details of the story – how far Bethany was from Jerusalem, why Jesus delayed his trip for two days, whether the Mary in the story is the same as the woman in Luke 7:37, why the Jews comforted Lazarus' sisters, and so on. Then he comes to the pastoral application, which has to do with how our Christian faith helps us deal with the death of someone we love. For Antiochenes, perhaps the main purpose of Scripture is to direct how we live our Christian faith in the world.

A little later in the course we'll see how these differing approaches to Scriptural interpretations led to distinct Antiochene and Alexandrian understandings of Jesus (i.e., christologies).

Augustine

Later in the course we'll have a lot to say about Augustine. For now we can say a couple of things about his approach to Scripture. First, in his Confessions, he recounts how he initially found Scripture distasteful both in its style and in its sometimes primitive morality, but under the influence of Bishop Ambrose of Milan he adjusted his interpretation of Scripture according to the principle that "the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life" (Book VI). It's plausible to see this discovery as his acceptance of Alexandrian principles, though he didn't reject Antiochene principles. Second, he borrowed from another North African some principles of the interpretation of Scripture based on an understanding of the rhetorical principles of speech; he presented these in his De Doctrina Christiana ("On Christian docctrine").

John Cassian

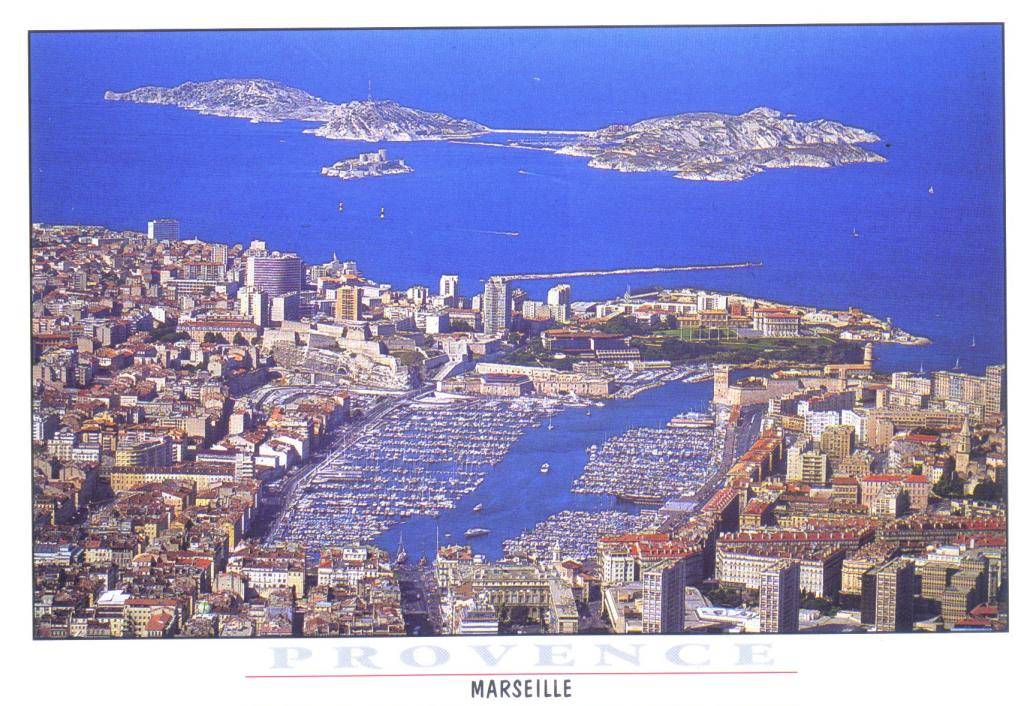

John Cassian (d. 433) was a monk whose abbey was on the port of Marseilles (spelled "Marseille" in French).  He borrowed from both the Alexandrian

and Antiochene approaches and developed a system for the fourfold interpretation of Scripture: he looked for the literal, typological (or allegorical), tropological,

and anagogical senses. This became the usual way of interpreting Scripture throughout the Middle Ages in the West, until the Protestant Reformation

sharply challenged it and the Enlightenment ridiculed it. (Here's a picture of Marseilles today, with le vieux-port in the middle and Cassian's abbey

somewhere at the middle left. The small island is the notorious Château d'If, of Count of Monte Cristo fame.)

He borrowed from both the Alexandrian

and Antiochene approaches and developed a system for the fourfold interpretation of Scripture: he looked for the literal, typological (or allegorical), tropological,

and anagogical senses. This became the usual way of interpreting Scripture throughout the Middle Ages in the West, until the Protestant Reformation

sharply challenged it and the Enlightenment ridiculed it. (Here's a picture of Marseilles today, with le vieux-port in the middle and Cassian's abbey

somewhere at the middle left. The small island is the notorious Château d'If, of Count of Monte Cristo fame.)

- Literal: the plain sense of Scripture; the historical events without attention to their deeper meaning.

- Typological: a consideration of how the Old Testament anticipates the New Testament, often by interpreting Old Testament passages as allegories of Christ's life.

- Tropological: the moral and pastoral application.

- Anagogical: the ultimate and spiritual sense, often relating to the Church triumphant in the world to come.

For instance, the story of David and Goliath can be read as:

- a story of something that happened in the history of Israel,

- a prefiguring of Christ's struggle with Satan in the wilderness (Goliath spent forty days confronting Israel, and Satan spent forty days confronting Jesus),

- a teaching about the strategies that we should adopt in spiritual combat, and

- the certainty of Christ's final victory over death.

The Antiochene approach will be seen particularly in the literal and the tropological, the Alexandrian in the typological and anagogical.

The fourfold method has been experiencing something of a revival, partly under the influence of an influential essay by the late John Webster (here's a link to an appreciation in pdf format) on the theological interpretation of Scripture. Here's a blog on the fourfold interpretation by a scholar at Oklahoma Baptist University.