What do modern approaches to history have in common?

Modern approaches to history are extremely various; in fact, modernity is characterized by experiment and revisionism. But as a useful starting point we can say that modern historians like to be “scientific” in their quest for truth, and they look to the natural sciences for models of method. So modern historians, like scientists, picture themselves making observations, asking questions, framing hypotheses, collecting and interpreting data, and testing conclusions. Now, historians, unlike most physical scientists, can’t create their own ev idence by setting up experiments. But at least one physical science, geology, knows that limitation as well; so the historians adapt.

idence by setting up experiments. But at least one physical science, geology, knows that limitation as well; so the historians adapt.

Modern historical method calls for the identification and the careful evaluation and “interrogation” of historical documents. Historians are supposed to free themselves from bias, approach evidence with open minds, and be doubtful of obvious and easy interpretations. The method excludes on principle conclusions derived from theological doctrine, philosophical premises, or political ends. In theory, if probably never in practice, historical conclusions can be relatively objective. But they also can never be finally definitive, since, as in the physical sciences, new evidence might appear that would require us to re-think our conclusions.

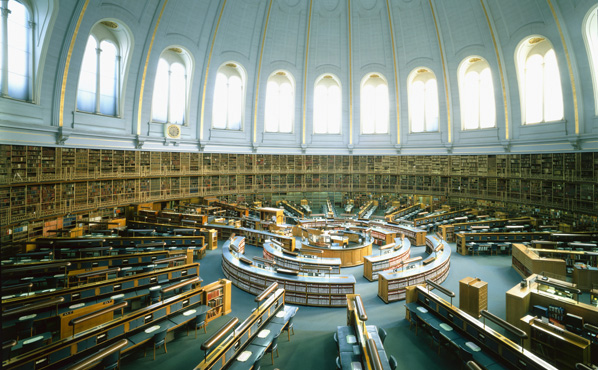

(The round reading room at the British Museum used to house the British Library, including its extensive archives of British and foreign history.)

What are the implications for approaching the history of Christianity?

Historians who take a modern approach to Christianity, unlike those who take a pre-modern approach, therefore don’t seek to validate a particular denominational tradition, or to discern God’s will in the complex processes of the human past. Detaching church history from theology has sometimes raised questions about its value in a theological curriculum. (Similar questions are raised about orienting Biblical  studies to the modern “higher criticism”.) For some theologians, the modern approach to the history of Christianity relativizes doctrine by rendering it the result, at least in part, of chance historical processes. Similarly, modern approaches can treat much Church tradition as an invention by the powerful to serve their interests. In these ways, historians can promote skepticism of Church teaching.

studies to the modern “higher criticism”.) For some theologians, the modern approach to the history of Christianity relativizes doctrine by rendering it the result, at least in part, of chance historical processes. Similarly, modern approaches can treat much Church tradition as an invention by the powerful to serve their interests. In these ways, historians can promote skepticism of Church teaching.

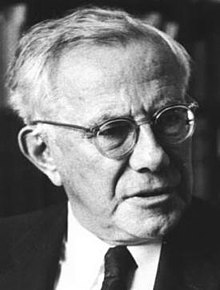

Ironically, although treating doctrine and tradition in this way can frustrate some theological purposes, it can serve others, as we saw with Valla’s debunking of the “Donation of Constantine”. Historical skepticism can be theologically beneficial for those who value what the theologian Paul Tillich (pictured here) called “the Protestant principle” of constantly questioning received theological truth-claims lest human constructions be mistaken for things of God, the root of idolatry.

The practice of modern history, requiring specialized skills in collecting and interpreting evidence, is frequently seen as a professional calling requiring advanced study and often involving memberships in scholarly guilds. In the nineteenth century, university departments of history emerged with degree specializations and curricula designed to teach historical scholarship. ‘Amateur’ historians, such as Edward Gibbon had been, were often made to feel a little unworthy.

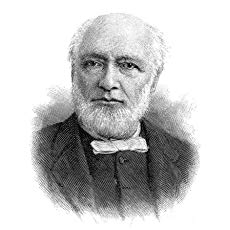

Church history became a scholarly discipline in North America through the leadership of Philip Schaff  (pictured here), who taught at Union Theological Seminary. He wrote an eight-volume History of the Christian Church according to modern, ecumenical, non-programmatic principles. In 1888 he founded the American Society of Church History (which had many Canadian members, including James Sheraton, the principal of Wycliffe College, Toronto). Schaff conceived of church history as an independent discipline in the orbit of theological studies, but his successors began to understand it as a species of historical studies. After his death, the ASCH dissolved itself in order to become a section of the American Historical Association. That arrangement was tense, and lasted only from 1896 to 1906, after which the ASCH was re-founded; but the ASCH continues to meet with the AHA, not with the theologians or the scholars of religious studies.

(pictured here), who taught at Union Theological Seminary. He wrote an eight-volume History of the Christian Church according to modern, ecumenical, non-programmatic principles. In 1888 he founded the American Society of Church History (which had many Canadian members, including James Sheraton, the principal of Wycliffe College, Toronto). Schaff conceived of church history as an independent discipline in the orbit of theological studies, but his successors began to understand it as a species of historical studies. After his death, the ASCH dissolved itself in order to become a section of the American Historical Association. That arrangement was tense, and lasted only from 1896 to 1906, after which the ASCH was re-founded; but the ASCH continues to meet with the AHA, not with the theologians or the scholars of religious studies.

Over the past generation some historians of Christianity have become uncomfortable being described as “church historians”, partly because they worry that the term could give the impression that they’re subservient to the interests of particular churches, and partly the term might seem to exclude the study of Christian things that happen outside churches. The ASCH, which has published the journal Church History since 1932, faced this debate in the 1990s. It decided to keep the title Church History but added the subtitle “Studies in Christianity and Culture.”

Some examples of modern approaches to the history of Christianity

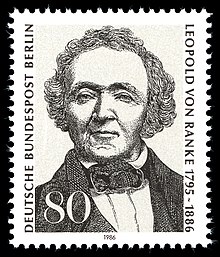

LEOPOLD VON RANKE

Leopold von Ranke, a German Lutheran, is widely regarded as the founder of modern historical scholarship (not that he was the first to advocate a ‘scientific history’). He didn’t focus exclusively on church history, but he was certainly engaged with the history of Christianity; he’s best known today for his Die römischen Päpsten, The Popes of Rome (1834–1836) in three volumes. (This is still in print, in both hard  copy and Kindle edition!) Von Ranke popularized the modern approach to history: original archival research rather than reliance on the packaged narratives written by other historians, the careful analysis of documents, the interpretation of texts in their own historical context, and narrative presentations of significant historical processes. He avoided moral judgments on historical figures; he rejected divine providence as a historical explanation; and he was skeptical of ready-made philosophies of history. He’s best known for saying that his professional objective was not to judge the past, nor to find instructive lessons from the past, but to report wie es eigentlich gewesen. This German phrase is usually translated “how things actually were,” although eigentlich has different possible shades of meaning.

copy and Kindle edition!) Von Ranke popularized the modern approach to history: original archival research rather than reliance on the packaged narratives written by other historians, the careful analysis of documents, the interpretation of texts in their own historical context, and narrative presentations of significant historical processes. He avoided moral judgments on historical figures; he rejected divine providence as a historical explanation; and he was skeptical of ready-made philosophies of history. He’s best known for saying that his professional objective was not to judge the past, nor to find instructive lessons from the past, but to report wie es eigentlich gewesen. This German phrase is usually translated “how things actually were,” although eigentlich has different possible shades of meaning.

Ranke’s influence persisted widely into the middle of the twentieth century. Lord Acton, who was appointed Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge University in 1895, admired von Ranke, and, following his lead, expressed optimism that reading primary sources properly could establish objective historical facts. (A modern historian, E.H. Carr, has called this view a “fetishism of facts.”) As late as 1967, Geoffrey Elton (d. 1994), a distinguished and widely respected professor of English constitutional history at Cambridge, maintained a substantially Rankean approach in his guide for advanced history students, The Practice of History. Nevertheless, not all modern historians presumed to be able to be free of bias; that part of von Ranke’s approach was challenged by such historians as Charles Beard, Carl Becker, R.G. Collingwood, and E.H. Carr.

The widespread Anglophone confidence that historians could be objective simply by studying evidence carefully led them to resist incursions into philosophical reflections on history. Historians should think like historians, not philosophers. Until the 1970s, and the challenge of post-modernism, most English-speaking historians remained untouched by European historical thinking that problematized the act of interpretation.

THE WHIG INTERPRETATION OF HISTORY

This phrase is the title of a book by Herbert Butterfield, a historian at Cambridge, in 1931. (His book is available on-line.) It described a kind of interpretive template by which many historians saw the past as a road to the present, an idea frequently connected with a confidence that history is a story of human progress. The term “whig” that Butterfield  used for his label was the name of a party in English politics between the 1680s and 1850s that opposed absolute monarchy and championed a constitutional monarchy reined in by Parliament. For Butterfield, the “whig interpretation” was a narrative that made the British constitutional monarchy a kind of inevitable result of centuries of constitutional developments and crises. Butterfield rejected this assumption of inevitable progress, which he thought led some historians to see the figures and events of the past as mere precursors to the present, instead of interpreting them in their own context. By the same token, many historians ignored past figures and events that failed to contribute to what they regarded as human progress, leaving them with a very incomplete portrait of the past.

used for his label was the name of a party in English politics between the 1680s and 1850s that opposed absolute monarchy and championed a constitutional monarchy reined in by Parliament. For Butterfield, the “whig interpretation” was a narrative that made the British constitutional monarchy a kind of inevitable result of centuries of constitutional developments and crises. Butterfield rejected this assumption of inevitable progress, which he thought led some historians to see the figures and events of the past as mere precursors to the present, instead of interpreting them in their own context. By the same token, many historians ignored past figures and events that failed to contribute to what they regarded as human progress, leaving them with a very incomplete portrait of the past.

The “whig interpretation” grew out of the kind of history-writing that focused on political and social elites that have held sway in governments, churches, and economies. It took little interest in labourers and farmers, minorities, and women. This prejudice was later challenged by social historians who took an interest in the everyday life of ordinary folks.

WALSH, MOIR, GRANT, A HISTORY OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH IN CANADA

H.H. Walsh, John Moir, and John Webster Grant shared the work on the three-volume A History of the Christian Church in Canada (1966–1972. It was an unprecedented and very ambitious project that still represents a kind of traditional modern Canadian historical scholarship at its best. The authors reviewed original sources, took into account secondary historical literature, and constructed a readable integrated historical narrative of Canadian Christianity in its social and political context. It particularly focused on two themes: what makes Canadian Christianity unique? And how has it helped shape Canadian identity? As Brian Clarke has noted (PDF), however, the work was little noted by most Canadian historians, partly because they mostly weren’t interested in religious history, but also because they were losing interest in the great theme of Canadian nation-building that had dominated Canadian historiography previously. Canadian historians were now moving into the social history of popular cultures and ordinary people.

Perhaps Canada’s most influential publishing venture in the history of Christianity — though its scope is wider than that — is the McGill–Queen’s Studies in the History of Religion series. Founded in 1988 by George Rawlyk, an evangelical Christian historian at Queen’s, it has published well over a hundred volumes.

FERNAND BRAUDEL AND THE ANNALISTES

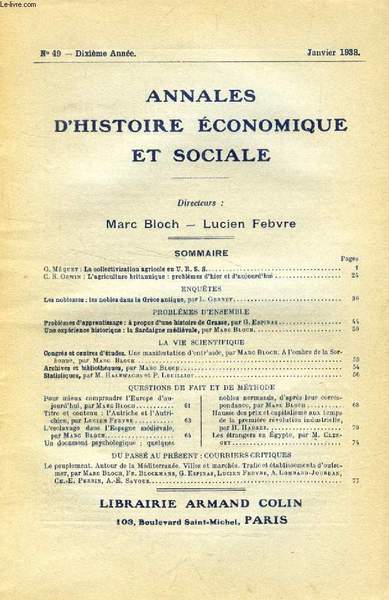

In 1929 Braudel (pictured here) helped found a game-changing academic journal called Annales d’histoire économique et sociale, and in 1949 he published his remarkable La Méditerranée et le Monde Méditerranéen à l'Epoque de Philippe II (1949). These landmarks established the importance of social history, which, while still working with  “modern” historical methods, established alternative frames of reference for understanding the past.

“modern” historical methods, established alternative frames of reference for understanding the past.

Braudel’s story goes something like this. During the 1920s he began a doctoral thesis on King Philip II of Spain, a sixteenth-century monarch. He decided that to understand Philip, he needed to the Spanish society of the day. Then he decided that to do that, he needed to understand Spain’s interrelations with other countries, which in turn required him to understand early modern economic systems. And to understand all that, he needed to understand geography and geology. So it was that he wound up with a study of the entire Mediterranean world in the sixteenth century, one that actually paid little attention to the details of King Philip’s reign.

This experience persuaded him of the relative insignificance of mere political, diplomatic, and military events and specific facts about the past, which he called histoire évenementielle. More important were medium-term, centuries-long realities (la moyenne durée), such as economic and social systems, and cyclical phases. These in turn, he saw, were shaped by millennia-long realities (la longue durée), such as geology, geography, and climate, and how societies interact with their environment. Historians, therefore, should apply the social sciences and natural sciences to investigate nature and persistent social structures. To do so they needed to synthesize as much evidence as possible of the whole breadth of human activity over long periods. For instance, they should study repetitive lists of social data, such census documents, market price reports, indications of rents and wages, and shipping logs. Bringing together information  about the whole breadth of human activity made a histoire totale possible.

about the whole breadth of human activity made a histoire totale possible.

This movement helped inspire many Anglophone historians after World War II to make use of sociological, anthropological, psychological, and economic theories and data in their approach to history. (These domains are often called, respectively, social history, cultural history, psychohistory, and economic history.) All this can still be considered a modern approach to history, valuing and analyzing historical evidence for what it can tell us about the past. Nevertheless, this approach disturbed more traditional historians in the Rankean tradition, who were highly suspicious of processing data through the filter of social-scientific theories, which, among other things, might be passing fashions.

SOME OTHER MODERN HISTORICAL METHODS

Cliometrics: originating in the 1950s, some historians compiled quantitative and statistical data to investigate economic and social history. An accessible example of the use of quantitative methods in researching the history of Christianity in Canada is Brian Clarke and Stuart Macdonald, Leaving Christianity: Changing Allegiances in Canada since 1945 (2017).

Complexity theory: this approach to history is influenced by the study of complex systems, which became a field in the 1970s. It recognizes that things happen unpredictably as a result of factors so numerous that they can’t be controlled or rationally mapped; instead, complex systems are adaptive and self-organizing. Some historians have therefore eschewed cause-and-effect narratives and considered random (“aleatory”) historical processes. An example is a doctoral thesis by C. Mark Steinacher, An Aleatory Folk: An Historical-Theological Approach to the Transition of the Christian Church in Canada from Fringe to Mainstream 1792—1898, Wycliffe ThD thesis, 1999.

Marxist theory (dialectical materialism): this approach privileges economic interest and class structure in the history of politics, ideology, and pretty much everything else. It was particularly popular in eastern Europe in the Communist period, serving the interests of Communist parties. But some English historians who regarded themselves as “philosophical Marxists”, free of party commitments, made very effective use of it. Most notable is E.P. Thompson,The Making of the English Working Class(1963), which includes a grou nd-breaking chapter on the influence of early English Methodism.

nd-breaking chapter on the influence of early English Methodism.

Oral history: this approach is particularly valuable in uncovering the experience of people that don’t create many texts. Special interviewing skills are required to encourage informants to speak freely. In Canada this approach is promoted by the Ontario Historical Association, the Canadian Oral History Association, and other groups. After the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement of 2007, thousands of testimonies of residential school survivors were created, which are now housed at the Natoinal Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. (Very few, however, are available; those that are available are difficult to find and search; and the NCTR staff are notoriously reclutant to answer enquiries.)

IDENTITY-BASED HISTORIOGRAPHY

In the 1960s, as history-writing about elites became less popular and social histories more popular, demographic groups that had been largely excluded from mainstream history books began to discover and construct their own histories. These groups include women, African-Americans, Latino/Latina populations, Indigenous populations, and sexually diverse groups. A label that’s sometimes used for this approach is “history from below”, but that comes from a Marxist milieu which limits its applicability. Identity-based approaches challenged traditional accounts which focused on elite cultures and the contributions of socially prominent white males. They found that marginalized groups exercised agency in social processes and social change. The research and writing of identity-based historians also helped create or define the identities of their constituency, and gave them a usable past.

Women’s history

This gained traction in the 1960s, connected with “second-wave” feminism. It quickly influenced the  writing of the history of Christianity. Among the pioneers in research into the history of Christian women were Elizabeth A Clark (pictured here), Natalie Zemon Davis, Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, and JoAnn Kay McNamara. Some male historians in the Rankean tradition questioned the approaches and results of women’s church history, partly because they thought that objectivity required being guided by the historical sources, in which women were under-represented. Indeed, since women seldom figured among the elites who visibly dominated church institutions, historians of Christian women usually wrote in the frame of social history, not the conventional Rankean style of church history. In Canada, significant monographs on the history of Christian women were slower to appear, but a good example is Elizabeth Muir and Marilyn Färdig Whiteley,Changing Roles of Women within the Christian Church in Canada(University of Toronto Press, 1995).

writing of the history of Christianity. Among the pioneers in research into the history of Christian women were Elizabeth A Clark (pictured here), Natalie Zemon Davis, Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, and JoAnn Kay McNamara. Some male historians in the Rankean tradition questioned the approaches and results of women’s church history, partly because they thought that objectivity required being guided by the historical sources, in which women were under-represented. Indeed, since women seldom figured among the elites who visibly dominated church institutions, historians of Christian women usually wrote in the frame of social history, not the conventional Rankean style of church history. In Canada, significant monographs on the history of Christian women were slower to appear, but a good example is Elizabeth Muir and Marilyn Färdig Whiteley,Changing Roles of Women within the Christian Church in Canada(University of Toronto Press, 1995).

Black history

African-American historiography. While there were historians of the black experience before the 1960s  (e.g., Carter Woodson, Benjamin Quarles, John Hope Franklin), who frequently wrote on American slavery, the civil rights movement and racial integration invigorated the field in the 1960s. Quarles’Black Abolitionists(1969) is sometimes seen as inaugurating a new historical approach in African-American studies, recognizing African cultural and religious backgrounds, and stressing black agency more than victimization. An example of a work that deals with the history of African-American Christianity is Albert Raboteau’s Slave Religion (Oxford, 1979), which used first-hand sources to trace black evangelijcal Christianity back to African religious roots. In Canada, Denise Gillard, who has degrees from Tyndale and McMaster Divinity College, has published some significant research on Canadian black church history.

(e.g., Carter Woodson, Benjamin Quarles, John Hope Franklin), who frequently wrote on American slavery, the civil rights movement and racial integration invigorated the field in the 1960s. Quarles’Black Abolitionists(1969) is sometimes seen as inaugurating a new historical approach in African-American studies, recognizing African cultural and religious backgrounds, and stressing black agency more than victimization. An example of a work that deals with the history of African-American Christianity is Albert Raboteau’s Slave Religion (Oxford, 1979), which used first-hand sources to trace black evangelijcal Christianity back to African religious roots. In Canada, Denise Gillard, who has degrees from Tyndale and McMaster Divinity College, has published some significant research on Canadian black church history.

Picture: Women in front of YWCA’s Ontario House, Toronto, ca. 1912 Photographer: William James City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1244, Item 71.22

History of colonized peoples

The decolonization of Africa and the granting of independence to West Indian countries in the 1950s and 1960s promoted the indigenization of African and West Indian university faculties and curricula, and triggered fresh historical research, often in the form of fieldwork. Religion has been an issue of particular interest in African studies, where ‘secularization’ is little noted. An early example is Edmund Ilogu, Christianity and Ibo Culture (1974). Notably, some of the early missionaries to the Ibo people were themselves African, including Samuel Ajayi Crowther, an Anglican bishop in Liberia who published A Vocabulary of the Ibo People in 1882. The first one-volume history of African Christianity is Elizabeth Isichei,A History of Christinaity in Africa (1995).

History of sexually diverse groups

The gay liberation movement in the U.S.A. is often dated to the Stonewall riots of 1969, following a police  raid on a New York inn. In the same year same-sex activity was decriminalized in Canada. A gay historiography emerged; an early gay historian recalls his anxiety at pioneering a new field: “I was choosing an area of research for which there was no context, no literature, no definition of issues, and no sources that had ever been tapped.” For Christianity, the controversial book Christianity, Homosexuality, and Social Tolerance (University of Chicago, 1980) by the Roman Catholic gay Yale historian John Boswell (pictured here) challenged common assumptions by arguing that early Christianity generally accepted homosexual lifestyles. His attempt pleased neither Christians who disapproved of homosexual practices, nor gays who disapproved of Christianity, and in any event a number of critical historians found his evidence weak. Gay historiography was succeeded by more complex understandings of sexual diversity often now referenced by the initials LGBTQIA.

raid on a New York inn. In the same year same-sex activity was decriminalized in Canada. A gay historiography emerged; an early gay historian recalls his anxiety at pioneering a new field: “I was choosing an area of research for which there was no context, no literature, no definition of issues, and no sources that had ever been tapped.” For Christianity, the controversial book Christianity, Homosexuality, and Social Tolerance (University of Chicago, 1980) by the Roman Catholic gay Yale historian John Boswell (pictured here) challenged common assumptions by arguing that early Christianity generally accepted homosexual lifestyles. His attempt pleased neither Christians who disapproved of homosexual practices, nor gays who disapproved of Christianity, and in any event a number of critical historians found his evidence weak. Gay historiography was succeeded by more complex understandings of sexual diversity often now referenced by the initials LGBTQIA.

Indigenous history in Canada

While there were many histories of missions to Indigenous peoples before the 1960s, they focused on the settler side of the encounter, and hardly at all on the influences on Indigenous history. Moreover,  repressive legislation all but silenced Indigenous voices. It became more feasible for Indigenous people to speak publicly about their history and identity, to advocate for themselves, and to publish, after amendments to the Indian Act in 1951 and 1960, which allowed First Nations people to vote, retain legal counsel, practice traditional ceremonies, and retain Indian status if they received a university degree. Some say the writings of Farley Mowat, beginning in 1952, helped shamed the Canadian government into beginning to recognize the humanity of Indigenous peoples.

repressive legislation all but silenced Indigenous voices. It became more feasible for Indigenous people to speak publicly about their history and identity, to advocate for themselves, and to publish, after amendments to the Indian Act in 1951 and 1960, which allowed First Nations people to vote, retain legal counsel, practice traditional ceremonies, and retain Indian status if they received a university degree. Some say the writings of Farley Mowat, beginning in 1952, helped shamed the Canadian government into beginning to recognize the humanity of Indigenous peoples.

Pictured: World War II soldiers from the Chippewas of Nawash First Nation: Steve Proulx, Rob McGregor, William Waukey, Eli Chegahno, Jonah Chegahno.

In the 1970s and 1980s much Indigenous historiography accepted but inverted the binary definitions of the colonial period, opposing "Native" in general to "Western" in general. For example, with James Dumont, a founder of the Native studies program at Laurentian University, “Western” ways of thinking were linear and rational, Native ways were holistic and spiritual. Similarly, the history of Native peoples since contact centred on their subjugation by settler people.

Before too long, however, more complicated accounts of interchange and networks of influence were being written, recognizing the different experiences of different Indigenous communities, and their agency in their own history. John Webster Grant’s Moon of Wintertime (1984) was a significant and impressive achievement, though some of his conclusions have been critiqued in recent years. Alan D. McMillan and Eldon Yellowhorn, Native Peoples and Cultures of Canada (1988), written collaborative by a settler scholar and a scholar from the Piikani Nation (formerly called the Peigan Nation), was the first general Canadian history of Indigenous people; its second edition is called First Nations in Canada (2004).

A fine study by Brenda MacDougall (pictured here), a Métis scholar at the University of Ottawa, was One of the Family: Metis Culture in Nineteenth-Century Northwestern Saskatchewan (2010), shows how one community negotiated opportunities with settler religious and economic institutions, and developed an identity rooted in Aboriginal values despite settler domination.

Christian history in Canada

In the 1960s and 1970s, writing the history of women, blacks, gays, and Indigenous persons corrected the against the white male heteronormative dominance of historiography. Christians weren’t seen as an identity-group in the same way, since they still represented the establishment, even though their history was largely excluded from mainstream Canadian historiography. (For instance, Martin L. Friedland’sThe University of Toronto: A History has not a word to say about the Toronto School of Theology.) Christians, unlike marginalized groups, were socially conspicuous; clergy sermons were often summarized in newspapers, the pronouncements of Christian leaders could influence political decision-making; governments afforded benefits to the churches.

But by the 1970s Canada could be seen as a post-Christian country. Many academics doubted, or even resented, the place of Christian studies at the university. In many respects Christians have gone from an influential mainstream constituency to a marginalized group. Some historians of Christianity now see themselves as one identity-based sub-discipline among others. Their job isn’t to win converts, any more than gay historians or Jewish historians or black historians want to win converts; but they interpret their past both for those who share that identity and for those who don’t.