What do pre-modern approaches have in common?

There are diverse pre-modern approaches to the history of Christianity, but an assumption common to most of them is that the past is important because God is at work in it. This assumption is based in the  Biblical confidence that the history of Israel and the history of the Church are meaningful because they are oriented to God’s purposes. Pre-modern historians don’t, however, unless they are very eccentric, presume to talk definitively about God’s will, since that’s the province of the Bible and, sometimes, the Church. And the Bible itself certain recognizes hat people of faith can disagree about what God is doing. But pre-modern historians may give strong suggestions of the unfolding of God’s will, for instance by calling attention to special signs or Biblical precedents.

Biblical confidence that the history of Israel and the history of the Church are meaningful because they are oriented to God’s purposes. Pre-modern historians don’t, however, unless they are very eccentric, presume to talk definitively about God’s will, since that’s the province of the Bible and, sometimes, the Church. And the Bible itself certain recognizes hat people of faith can disagree about what God is doing. But pre-modern historians may give strong suggestions of the unfolding of God’s will, for instance by calling attention to special signs or Biblical precedents.

Pre-modern Christian historians mostly write narratives of Christian leaders, martyrs, missionaries, thinkers, and holy disciples. Their frequent themes are the spread of Christianity, conversion, persecution (red martyrdom) and asceticism (white martyrdom), service, the clarification of Christian truth, the leadership of holy individuals, and the punishment of evil-doers. They use independent sources, which they sometimes identify and defend. (Stories of the past that don’t use sources can easily cross the vague boundary from history into legend.)

Pre-modern histories of Christianity can take on an explicitly partisan and polemical tone when they are serving a purpose of advocacy, for instance to justify one side in a dispute, a controversial leader, a schismatic group, or a particular approach to Christianity.

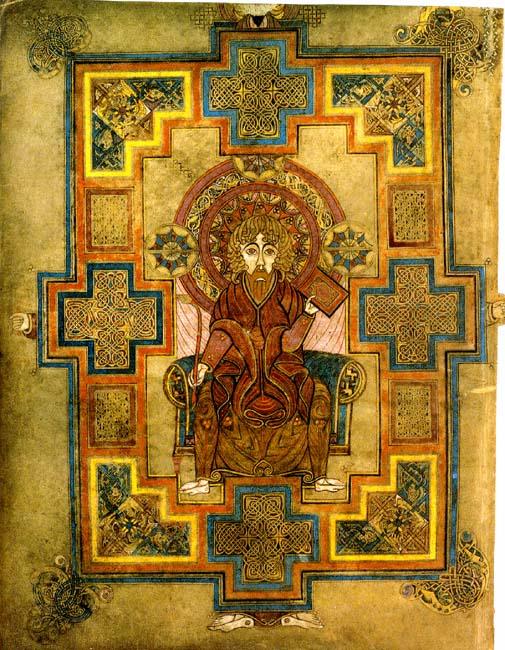

Here are a few examples of pre-modern Christian histories.

THE ACTS OF THE APOSTLES

Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament is the earliest Christian Church history. It highlights the Church’s geographical spread, its leaders, its preaching, its relation to the wider society, and its organization,  discipline, and disputes. Early readers were apparently conflicted about the Church’s outreach to Gentiles, especially the question whether Gentiles came under the obligation of the law of Moses. Acts gives an account of the apostles decided to except Gentiles from the rigour of the law. Nevertheless, Acts sees the Church as maintaining its continuity with Israel.

discipline, and disputes. Early readers were apparently conflicted about the Church’s outreach to Gentiles, especially the question whether Gentiles came under the obligation of the law of Moses. Acts gives an account of the apostles decided to except Gentiles from the rigour of the law. Nevertheless, Acts sees the Church as maintaining its continuity with Israel.

The approach that Acts takes to history has roots in both Greco-Roman traditions and in Hebrew traditions. We see the Greco-Roman influence, for instance, in the author’s following affirmation: “I ... decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been instructed.” This statement resembles the approach of some earlier Greek historians. (This passage occurs at the beginning of the Gospel of Luke, the companion volume of Acts.) Similarly, when Acts quotes sermons preached by the apostles, the reader may be reminded that the Greek historian Thucydides used to quote long political speeches, without pretending that they were precise transcripts. As for the Hebrew influence on Acts, we see that in the book’s quotations from the Hebrew Scriptures and its use of Hebrew thought categories, including the premise that God ultimately rules human affairs, and gives direction to affairs of the people of God.

The author of Acts doesn’t explicitly evaluate the historical sources that are being used, doesn’t discuss alternative interpretations of the Church’s story, orients the narrative to theological purposes, and writes in a very clear and literate style. All these features are characteristic of pre-modern historiography.

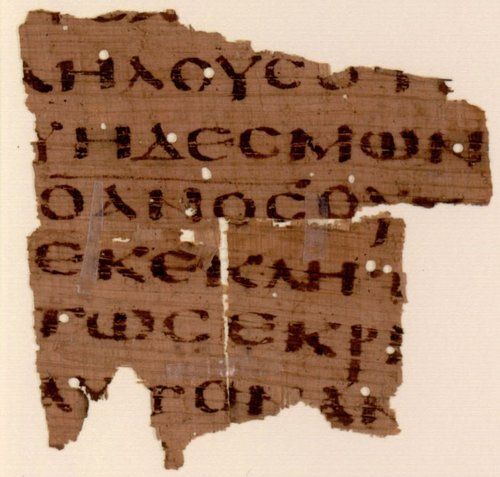

EUSEBIUS' HISTORY OF THE CHURCH

Eusebius of Caesarea, who was bishop of a diocese with a well stocked library and archives, published his  final version of his History of the Church in 325. It’s a full-length work in ten parts (called books).

final version of his History of the Church in 325. It’s a full-length work in ten parts (called books).

Eusebius frequently quotes first-hand sources at length, and does so with reasonable though not scrupulous accuracy in cases when the quotations can be checked. By quoting, Eusebius has preserved to posterity many historical materials which would otherwise have been lost. As a rule, however, he doesn’t interrogate his sources critically.

ATHANASIUS' LIFE OF ST. ANTONY

Athanasius' influential work tells the story of Antony, a famous Egyptian Christian ascetic and monastic leader who was known for his almost super-human spiritual discipline and his extraordinary wisdom. The book was published shortly after Antony’s death in 356, and was soon available in Coptic, Greek, Latin, and Syriac  versions. It was one of the most popular Christian books of the age, and became perhaps the single most influential model for the enduring literary genre known as the saint’s life, or hagiography. (The work, in an older translation, is here.)

versions. It was one of the most popular Christian books of the age, and became perhaps the single most influential model for the enduring literary genre known as the saint’s life, or hagiography. (The work, in an older translation, is here.)

Like most pre-modern writings about the past, the Life of Antony doesn’t conform to modern ideas of what a history book should be. Saints’ lives include a few facts, many embellishments, stock incidents, and sheer inventions, and it’s impossible to be confident which is which. (A group called the Bollandist Society, founded in the seventeenth century, is devoted to the critical study of hagiographic literature.)

The author of the Life of Antony was the bishop of Alexandria, the principal diocese of Egypt, where Antony lived. Athanasius evidently had some personal acquaintance with Antony, and one of his sources for his biography, as he tells us in its introduction, was simply what he was able to call to mind from his own knowledge. His evidence also included some interviews that he conducted with a few of Antony’s monks. But the reader senses that Athanasius was willing to embellish the evidence, since he says that his main purpose in writing is to present Antony as a model, “that you may bring yourself to imitate him.” Athanasius takes the opportunity to project his own views of the model Christian onto his portrait of Antony: the monk is obedient to his bishop, allergic to worldliness, suspicious of worldly authorities, skeptical of pagan philosophy, orthodox in Athanasius’ way of orthodoxy, and respectful of Scripture. Some scenes in the Life of Antony may have been adapted from Biblical stories. Like Acts of the Apostles and Eusebius’ History of the Church, Athanasius was evidently familiar with a range of non-Christian literature; in fact, some scholars think that the Life of Antony may have adapted some secular biographies.

BEDE'S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH PEOPLE

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed about 731, may be the most admired work of medieval history-writing. (The text, in an older translation, is here.)

Bede was a monk in an Anglo-Saxon kingdom that included what’s now northeast England and southeast Scotland. He had a natural curiosity, a brilliant mind, and access to a very  fine library. He was clearly influenced in his approach to his task by Eusebius’ History of the Church.

fine library. He was clearly influenced in his approach to his task by Eusebius’ History of the Church.

The title of his book is telling: a single nation called “England” didn’t yet exist, but Bede was promoting the idea that the various kingdoms of the day had an “English-ness” in common. (But he evidently did favour the kingdom where lived, which was called Northumbria.)

Bede begins his history by talking about the early evangelization of Britain when it was a province of the Roman Empire, but he’s more interested in things that happened after Germanic peoples settled there in the early fifth century. They were evangelized from the north by Irish missionaries and from the south by missionaries sent from Rome; by the seventh century, these two styles of Christianity were coming into conflict. In Bede’s narrative, the English accepted the Roman obedience, and Bede is clearly satisfied with that choice. Interestingly, however, he doesn’t disparage the losing side, as the winners of historical conflicts so often do. Instead, he writes about the Irish missionaries, saints, poets, and musicians with immense admiration. But actually we know that the choice for Rome wasn’t nearly as definitive in Bede’s day as his writing suggests, and his even-handed approach may have been intended to conciliate the remaining supporters of a Celtic style of Christianity.

Bede made the very specific significant contribution of dating events “in the year of our Lord” (A.D.), or as many would now call it, in the “common era” (C.E.). This system quickly replaced dating according to the regnal years of monarchs and emperors, which was confusing since it meant that every country followed its own system of dating.

LORENZO VALLA, TREATISE ON THE DONATION OF CONSTANTINE

Lorenzo Valla’s Treatise on the Donation of Constantine (its title is fancier in the original Latin), written in 1440, anticipates modernity in its critical focus on the historicity of a particular text, although it looks pre-modern  in the ease with which it moves into theological arguments. (Its text, in Latin and English parallel, is available here.) Valla was a priest, a teacher of rhetoric, and, when he wrote this work, a secretary in the royal court of King Alfonso of Aragon (now part of Spain). He was a fine example of the spirit of the Italian Renaissance, with its revival of the learning of classical Greece and Rome, its passion for classical sources, and its respect for the power of rhetoric.

in the ease with which it moves into theological arguments. (Its text, in Latin and English parallel, is available here.) Valla was a priest, a teacher of rhetoric, and, when he wrote this work, a secretary in the royal court of King Alfonso of Aragon (now part of Spain). He was a fine example of the spirit of the Italian Renaissance, with its revival of the learning of classical Greece and Rome, its passion for classical sources, and its respect for the power of rhetoric.

Valla’s purpose was to debunk the document known as the “Donation of Constantine,” a forgery created in the years before or after 800. It purported to be a deed of gift by the Emperor Constantine in the fourth century to the Pope of Rome, handing over a considerable package of property and jurisdiction. The Church used the document to support its claims of authority. Valla, in attacking the document and therefore one of the foundations of the Pope’s authority, was serving his royal sponsor, who was in the midst of territorial disputes with the Pope.

Valla’s most telling critique of the “Donation of Constantine” was an original and creative one: demonstrating in detail that in its language and social references the “Donation” simply couldn’t have been written in Constantine’s time. This was a powerful use of the principle of “anachronism” as a tool of historical criticism. Valla brought the argument home effectively, given his command of Latin language and rhetoric, and his awareness that languages are historical phenomena that change over time.

The term “Renaissance thinker,” meaning a polymath who works easily in different fields, applies to Valla, and distinguishes him from modern scholars, who usually see themselves as specialists. Most of Valla’s treatise moves well beyond what a modern historian would regard as appropriate by marshaling arguments from canon law, theology, and political theory in order to delegitimize papal claims.

JOHN FOXE'S ACTS AND MONUMENTS

John Foxe’s The acts and monuments of things passed in every king’s time in this realm, specially in the Church of England appeared in its second and most noteworthy edition in 1570. (The text is available here.) It’s a great example of western church  histories that were written in the wake of the Reformation of the sixteenth century. It’s a partisan church history by a Church of England controversialist that demonstrates the superiority of the English Church by telling its story, at the expense of the Church of Rome. Calvinists and Lutherans also wrote histories vindicating their separation from Rome; and, similarly, Roman Catholics wrote histories that demonstrated their victory over Protestant errors, Quakers and Baptists and Methodists wrote histories that justified their rejection of the Church of England, and so on. Pre-modern denominational histories were powerful tools in theological education before the age of ecumenism. They gave a story form to theology. Without framing direct theological arguments for their church’s doctrine, they showed how their church had organized itself around the truth, against the errors of its rivals. Often they portrayed their own leaders as wise and good, the leaders of other churches as defective, which added a dramatic punch to the narrative.

histories that were written in the wake of the Reformation of the sixteenth century. It’s a partisan church history by a Church of England controversialist that demonstrates the superiority of the English Church by telling its story, at the expense of the Church of Rome. Calvinists and Lutherans also wrote histories vindicating their separation from Rome; and, similarly, Roman Catholics wrote histories that demonstrated their victory over Protestant errors, Quakers and Baptists and Methodists wrote histories that justified their rejection of the Church of England, and so on. Pre-modern denominational histories were powerful tools in theological education before the age of ecumenism. They gave a story form to theology. Without framing direct theological arguments for their church’s doctrine, they showed how their church had organized itself around the truth, against the errors of its rivals. Often they portrayed their own leaders as wise and good, the leaders of other churches as defective, which added a dramatic punch to the narrative.

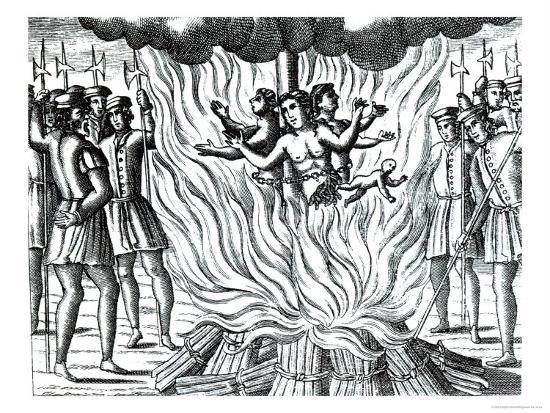

Foxe told the story of the Church of England from earliest times down to his own age. Taking from Eusebius the idea that the Church is a society of martyrs, he showed the superiority of the Church of England over the Church of Rome by describing the former as persecuted by the latter. Because of its many bloody stories of martyrdoms, and, even more effectively, its vivid woodcuts, his book was commonly called the Book of Martyrs. The value of Acts and Monuments in the Church of England was recognized in 1571 when instructions were given to cathedrals and parish churches to make copies available to be read by the people. To be sure, these instructions weren’t widely followed. But the book gave the Church of England a strong integrated story. Since the Church of England was the established church of the country, Acts and Monuments also helped reinforce the sense of the English people that they were an elect nation.

Nevertheless, Foxe was no mere propagandist. He tirelessly gathered primary sources from far and wide, and quoted them, sometimes at length, and with great accuracy. He didn’t simply invent evidence. Modern scholarship has generally corroborated the factual basis of Foxe’s stories, where external evidence has been available.

EDWARD GIBBON, DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in six volumes published between 1776  and 1789, may be the most accomplished example of pre-modern history. Gibbon’s command of centuries of source material across the Mediterranean world and beyond is breathtaking, and his writing style — descriptive, evocative, subtle, witty — is indescribably masterful. The modern historian Hugh Trevor-Roper called it “probably the most majestic work of history ever written.”

and 1789, may be the most accomplished example of pre-modern history. Gibbon’s command of centuries of source material across the Mediterranean world and beyond is breathtaking, and his writing style — descriptive, evocative, subtle, witty — is indescribably masterful. The modern historian Hugh Trevor-Roper called it “probably the most majestic work of history ever written.”

The text is available here.

The Decline and Fall isn’t categorized as a history of Christianity, but Gibbon acknowledges that he has made use of church history, and Christianity takes centre stage in his narrative. Gibbon argues that Christianity, with its divisive theological in-fighting, its waste of wealth on pointless religious devotion, its indolent monks, its preaching against active social virtues, among other things — fatally undermined the political health, military strength, and morale of the Roman Empire.

The very attempt to write about the entire Roman Empire, on the basis of a mass of documents so extensive that they couldn’t all be individually critiqued, led Gibbon into a generalized narrative that later historians distrusted. To a modern mind, which views evidence as multivalent, cultures as complex, societies as stratified, and historical judgments as probabilistic, Gibbon hammered where he ought to have probed. He therefore seemed to read his sources not for their hints of the unexpected, but for their assistance in supporting his conclusions.